THE YEARLY READER

1964: The Fizz Kids

An upstart Philadelphia ballclub, leading the National League by 6.5 games with less than two weeks to play in the regular season, collapses under the exhausted weight of a two-man rotation—leading to manager Gene Mauch’s first career heartbreak.

Philadelphia fans received World Series tickets as the Phillies were convinced they were headed to a National League pennant; instead, the team’s October dreams went up in flames after one of the most historic season-ending chokes ever seen.

On September 20, 1964, a betting man would have gladly put his house on the Philadelphia Phillies winning the National League pennant.

With 12 games left to their regular season, the Phillies held a 6.5-game lead over both the St. Louis Cardinals and Cincinnati Reds. Their magic number was six, a number representing the combination of Phillies wins and losses by either the Cardinals or Reds needed to clinch first place. The trailing two teams were mathematically still in it, a nice way of saying their chances were all but nil. The Phillies had their next seven games at home, were given permission to print World Series tickets, and team ace Jim Bunning was photographed for a Sports Illustrated cover previewing a World Series certain to include the Phillies.

What was expected to be a celebration to the end of a three-year journey from the extreme depths of the NL basement to the World Series would, instead, become one of baseball’s most shocking plunges from assured triumph.

After last winning the NL pennant in 1950, the Phillies gradually deteriorated through the next decade, their off-field antics affecting their on-field play. Just ask Eddie Sawyer, the skipper of the 1950 team who was fired in 1952, then brought back in 1958. What he saw the second time ultimately led him to flee. “I’m 49,” Sawyer said after resigning a single game into the 1960 season, “and I’d like to see 50.”

Succeeding him was 34-year-old Gene Mauch, a utility player who bounced in and out of the majors before bringing a fiery personality to his new calling as manager. Mauch cleaned house, starting a youth movement that resulted, in his first full year piloting in 1961, with a horrendous 47-107 finish that included a major league-record 23-game losing skid. But the seeds were sown and flowered quickly a year later when the Phillies jumped to a game above .500. They further improved in 1963, finishing fourth.

Two major additions sprung the Phillies into first place in 1964. Jim Bunning, feeling unappreciated in Detroit, was traded to Philadelphia and showed the Tigers how much value they lost by producing the first of three straight years winning 19 games. And although Johnny Callison was emerging as a midseason favorite to win the NL Most Valuable Player award, it was rookie Dick Allen—on his way to setting a NL rookie record for most total bases—who had the most potent bat in the Phillies lineup. The headstrong 22-year old batted .318 with 29 home runs, 91 runs batted in, and led the league with 13 triples and 125 runs scored.

BTW: Why no MVP for Allen? Perhaps it was in his defense—committing 41 errors at third base.

Bunning confirmed his status as the new Phillies ace on Father’s Day, when the father of six threw the first perfect game in modern-day NL history at New York against the Mets. Complementing Bunning in the rotation was 26-year-old lefty Chris Short, whose year-by-year growth would continue in 1964 with a 17-9 record and outstanding 2.20 earned run average.

While the Phillies coasted through the summer, their contenders dealt with various issues that kept them out of total focus. Cincinnati manager Fred Hutchinson took several leaves of absence to fight a growing cancer, while San Francisco skipper Al Dark nearly created a mutiny with the Giants’ talented group of black and Latino players after he told a reporter that they lacked “mental alertness.” And in St. Louis, Cardinals general manager Bing Devine, his authority undermined by 82-year-old “special consultant” Branch Rickey, was fired at midseason by owner Gussie Busch.

BTW: The non-white Giants players wanted to boycott, but Willie Mays cooled everyone down; Dark said he was misquoted.

One of Devine’s last trades would later convince Busch, in hindsight, that he had made a mistake in firing him. Lou Brock, a speedy outfielder with some pop, had been rushed to the majors by the Chicago Cubs and mistaken for a big-time slugger. Thus he was terribly out of sync. The Cubs were no less thrilled with Brock’s performance than Brock was being there. So when Devine called and asked the Cubs for Brock in exchange for pitcher Ernie Broglio—the winner of 60 games over his previous four seasons—the Cubs jumped at the offer.

In St. Louis, Brock was told by manager Johnny Keane—whose own job was rumored to be on the line—to stop swinging for the fences; just get on base and steal at will. This was music to Brock’s ears, and he responded as a born-again player. In 103 games with the Cardinals, Brock hit .348, stole 33 bases and scored 81 runs.

BTW: While Brock would go on to collect some 2,700 hits and 900 stolen bases for the Cardinals, Broglio would go 7-19 over what would be his final two-plus major league seasons in Chicago.

The Phillies’ 6.5-game lead held firm as the team came home for their final dozen games. But the rotation presented a problem for Gene Mauch; Art Mahaffey and Ray Culp both had sore arms, and he’d lost faith in a third starter, Dennis Bennett. Thus, he hatched a scheme that would leave a lot of people scratching their heads for a long time: Using his two best starting pitchers—Jim Bunning and Chris Short—as much as possible, often on just two days’ rest. It seemed a desperate measure reserved for a team trying to come back from, not leading by, 6.5 games.

The Phillies opened their seven-game homestand with three against the Reds. They were swept. Next came the Milwaukee Braves, out of the running but nonetheless still dangerous, for four games. The Phillies got swept again. Not even Johnny Callison’s three home runs could save Philadelphia in its final game against the Braves; Bunning was shelled, 14-8, and the Phillies completed a 0-7 week at home.

Stunned and in shock, the Phillies suddenly found themselves in third place to two teams riding winning streaks—the first-place Reds with nine straight wins, and second-place St. Louis with five. Worse, the Phillies would have to finish the season on the road against both teams. Mauch desperately tried to fire his players up, but his rants evaporated through an emotionally traumatized unit. He insisted on continuing to use Bunning and Short almost exclusively, though the exhausted pair had little left. “These are my aces…and you can bet we’ll (win the pennant),” a transparently upbeat Mauch declared to the press, before lowering his head and muttering, “I hope.”

The collapse continued in St. Louis. The dazed and staggered Phillies extended their losing streak to 10 games after being swept by the Cardinals, leaving them with one last, faint hope: A sweep of the Reds in a short two-game set to finish the year, combined with three straight Cardinal losses against the lowly Mets, to create an unprecedented three-way tie for first. The Phillies, suddenly revived back to life, lived up to their end of the bargain by taking both games at Cincinnati; with utter astonishment, the Mets nearly did the same—winning the first two of three contests at St. Louis before losing the finale (11-5, to Bob Gibson) to give the Cardinals the NL flag by a single game over the Phillies and Reds.

BTW: The Cardinals had the Phillies’ number during the regular season, winning 13 of 18 contests…The defending NL champion Los Angeles Dodgers dropped to a sixth-place tie, burdened by weak hitting and a pitching staff that became unreliable once past Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale.

Pitching on Empty

Phillies aces Jim Bunning and Chris Short were just a few weeks away from wrapping up spectacular campaigns when manager Gene Mauch decided to overwork both pitchers through the team’s infamous home stretch. Here’s how both pitchers fared during the Phillies’ 10-game losing streak, as compared to the rest of the season.

In getting a ticket to the World Series for the first time in 18 years, the Cardinals featured a solid veteran infield led by third baseman and NL MVP Ken Boyer (.295 average, 24 home runs, 119 RBIs) and first baseman Bill White (.302, 21, 102). Along with Brock, the outfield included Curt Flood, whose league-leading 211 hits punctuated a .311 batting average. And while Ray Sadecki led the Cardinals with 20 wins, the go-to man on the staff clearly became 28-year-old right-hander Bob Gibson. If Sandy Koufax was the game’s most unsolvable pitcher, then Gibson was its most intimidating, showing off an intensely fierce disposition that opposing batters dared not mess with; Gibson’s 19-12 record, 3.01 ERA and 245 strikeouts were definitely proof of that.

The American League pennant race wasn’t as crazy, but no less nail-biting, as that of the NL.

In New York, Yankees manager Ralph Houk had been kicked upstairs to the general manager spot to make way for his successor in the loveable Yogi Berra. It was an attempted reinvention of the Yankee Way, to liven up the cold, corporate persona of the four-time defending AL champs to compete with the wildly popular (yet still totally awful) Mets across town. Berra understood what winning as a Yankee was all about, but being manager also meant the discomfort of having to be a disciplinarian upon a group of players who just the year before were his teammates, his equals, his friends.

This latter understanding would be no more painful for Berra than on a hot August afternoon in Chicago, after the Yankees were swept by the front-running White Sox. At the back of the team bus sat utility infielder Phil Linz, so upset about his limited playing time that he started jamming Mary Had a Little Lamb on his harmonica. Berra, seated at the front of the bus, shouted at Linz to knock it off. Linz turned to Mickey Mantle, sitting nearby, and asked what Berra had said. Mantle said, “Play it louder,” to which Linz did. Showing what little dark side he had in him, Berra stormed back and slapped the harmonica away from Linz. The incident made headlines, and seemed to underscore an evolving, indifferent Yankee attitude to a pennant race seemingly slipping away from them.

BTW: Linz was fined $200, but made it up and more when a harmonica company asked him to endorse their products for $5,000.

Sleep in, Catch Up

During the Yankees’ second five-year run of AL superiority (1949-53 being the first), fast starts were anything but common. This list shows how far back in the standings they were before powering up late to grab, once again, the AL flag.

Events of the season’s final six weeks brought the familiar gap-toothed smile back to Yogi’s face. The Yankees went on a winning rampage, fueled by the late-season additions of called-up starter Mel Stottlemyre (9-3, 2.06 ERA in 13 appearances)—and starter-turned-closer Pedro Ramos (one win, eight saves—and no walks—over 22 innings), who slaved with decidedly losing teams for 10 years. New York won 30 of its last 40 games, a run which included an 11-game win streak, to leapfrog over the White Sox and the league’s other serious contender in the Baltimore Orioles. A nine-game win streak by the White Sox to finish the year was too little, too late; the Yankees captured their fifth straight AL pennant by a game over Chicago and two over the Orioles—whose September chances were handicapped when they lost lead power source Boog Powell (39 homers, 99 RBIs over 134 games).

The 1964 World Series was represented by two teams that showed big league baseball at the crossroads: The power-laden, good ol’ white boy winning tradition of the New York Yankees against the aggressive, multi-ethnic speed and strength of the St. Louis Cardinals.

The two most revered Yankees—Mickey Mantle and pitcher Whitey Ford—were barely intact after each performed the last great campaign of their careers. Ford’s arm was practically dead on arrival in St. Louis for Game One, which he lost 9-5; he would be on the shelf for the rest of the Series. Mantle hit beautifully, batting .333 with three homers—including a ninth-inning walk-off solo shot to win Game Three, 2-1, but his fielding had become a liability. Moved to right field, his mobility was shot and his range decreased, and the fast and forceful Cardinals runners took extra bases at will on the once-feared outfielder.

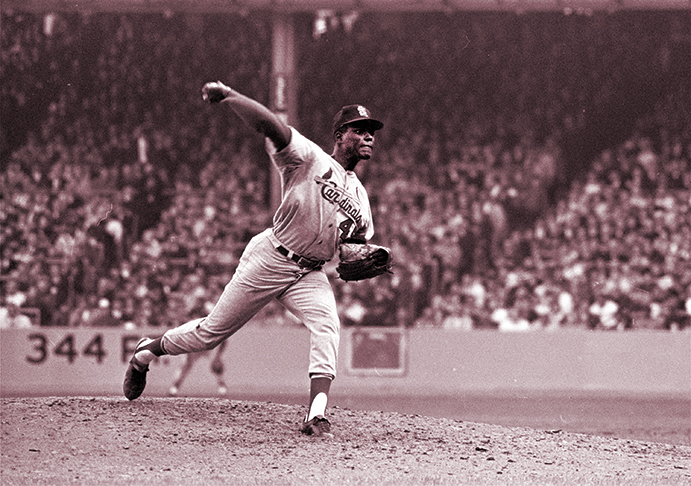

The Yankees had heard about Bob Gibson, but they were about to discover him up close and personal. They got past him in Game Two, scoring four runs through eight innings before adding four more in the ninth on an ineffective Cardinals bullpen to run away with an 8-3 win. Gibson wouldn’t need relief in his next two starts. In a pivotal Game Five, he took a 2-0 lead into the ninth, lost it when Tom Tresh tied it up with a home run, but won it back in the 10th, 5-2, after catcher Tim McCarver hit a three-run shot to give St. Louis the victory. On two days’ rest, Gibson took the mound for Game Seven and, although the fatigue took some of the edge off his sharpness, he got the job done—going the distance and outdueling Mel Stottlemyre, who, also pitching on two days’ rest, didn’t make it past the fifth inning. The Cardinals took the World Series with a 7-5 win.

Bob Gibson’s star hits the national stage in the World Series as the St. Louis ace hurls a 10-inning victory over the Yankees in Game Five; he would finish New York off three days later with another complete-game performance in Game Seven. (Associated Press)

For sheer, surprising drama, the days after the World Series were about as exciting as the Series itself. Cardinals manager Johnny Keane, having endured public rumors of being replaced in midseason, stuck it to owner Gussie Busch—handing him his resignation as he sat down beside him at a post-Series press conference. Using the “If you can’t beat him, hire him” school of thought, the Yankees fired a speechless Yogi Berra—who thought he had brought his team around to be his own—and replaced him with Keane.

It seemed the logical recipe for the Yankees to stay atop the baseball world. Instead, they were about to be introduced to a prolonged period within its underbelly.

Forward to 1965: The Fall of the Yankee Empire After decades at the top, the New York Yankees are brought down by a combination of old age, nagging injuries and arrogance.

Forward to 1965: The Fall of the Yankee Empire After decades at the top, the New York Yankees are brought down by a combination of old age, nagging injuries and arrogance.

Back to 1963: The Sandman Cometh After years of wildness and frustration, the Los Angeles Dodgers’ Sandy Koufax becomes an ace for the ages.

Back to 1963: The Sandman Cometh After years of wildness and frustration, the Los Angeles Dodgers’ Sandy Koufax becomes an ace for the ages.

1964 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1964 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1964 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1964 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1960s: Welcome to My Strike Zone In a decade where baseball as a tradition is turning stale with America’s emerging counter-culturism, major league owners see its biggest problem to be, of all things, an overabundance of offense in the game. The result? An increased strike zone, further contributing to a downward spiral in attendance, but greatly aiding an already talented batch of pitchers.

The 1960s: Welcome to My Strike Zone In a decade where baseball as a tradition is turning stale with America’s emerging counter-culturism, major league owners see its biggest problem to be, of all things, an overabundance of offense in the game. The result? An increased strike zone, further contributing to a downward spiral in attendance, but greatly aiding an already talented batch of pitchers.

Dick Ellsworth recalls life as a Chicago Cub during the early 1960s—surviving the nutty College of Coaches and the heartbreak of losing young teammate Ken Hubbs in a plane crash.

Dick Ellsworth recalls life as a Chicago Cub during the early 1960s—surviving the nutty College of Coaches and the heartbreak of losing young teammate Ken Hubbs in a plane crash. Ernie Broglio reveals that the St. Louis Cardinals knew he was damaged goods when they traded him to the Chicago Cubs for Lou Brock.

Ernie Broglio reveals that the St. Louis Cardinals knew he was damaged goods when they traded him to the Chicago Cubs for Lou Brock.