THE YEARLY READER

1975: Birth of a Renaissance

Sparked by rookies Fred Lynn and Jim Rice, the Boston Red Sox tangle with Cincinnati’s Big Red Machine in a World Series considered one of the greatest ever—reawakening America’s passion for baseball after a decade spent in the doldrums.

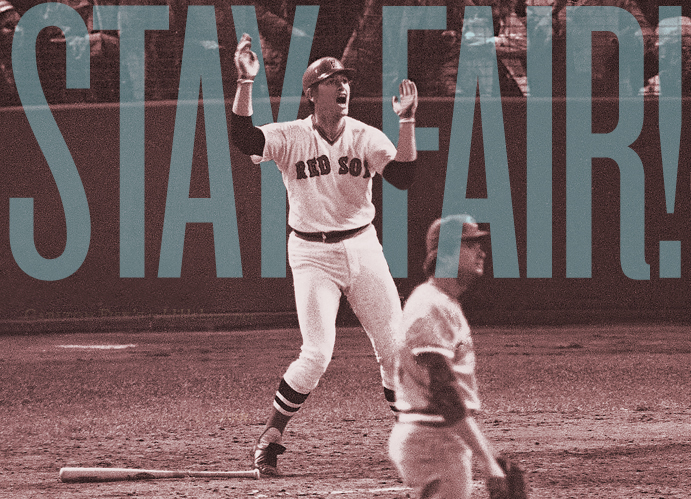

Carlton Fisk’s indelible home run didn’t help win the World Series for the Boston Red Sox, but it did help put a positive jolt back into baseball after suffering through a decade-long malaise. (Associated Press)

For over a decade, Major League Baseball seemed stuck in a stubborn recession, living a dull and archaic existence in an era of counterculture and future shock. Few appeared satisfied with baseball’s state of affairs; the casual fans increasingly turned away from the abundant low-scoring games and snail-like pacing, while diehard purists detested the advent of artificial turf and the designated hitter.

As major league attendance stagnated, baseball’s ego was bruised by the rise of pro football, which became king of American spectator sports by the mid-1970s. But the NFL represented only a modest slice of baseball’s external worries, given the sudden glut of pro sports competition from the NBA, NHL, ABA, WHA, NASL, WFL, PGA, LPGA, NLL, NASCAR, Muhammad Ali and World Team Tennis. Baseball, which used to have the summer all to itself, now had to market the sport far beyond the bland signage outside the gates announcing, “Game Today.”

The National Pastime’s savior came in what many now consider the greatest World Series ever played. A thoroughly exciting seven-game set between the Cincinnati Reds and Boston Red Sox in October 1975 re-awakened America’s passion for baseball, giving the sport a shot in the arm in the purist of ways: By selling the game itself.

Playing solid baseball for eight years since winning the 1967 American League pennant at rustic, loveable Fenway Park, the Red Sox had long since found little difficulty reconnecting with their loyal legions in Beantown and beyond. Their consistent winning was matched, however, with a consistent frustration of not reaching that next level, always finishing second or third with eighty-some wins and seventy-some losses.

Out of nowhere in 1975, the Red Sox were blessed by the arrival of not one, but two blue-chip rookies who would instantly rise to stardom and put Boston back on the top shelf.

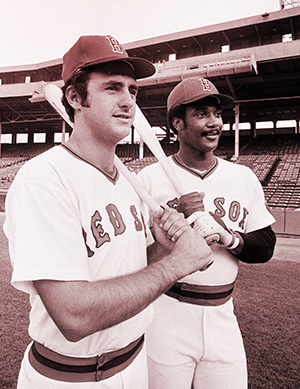

Fred Lynn and Jim Rice had destroyed International League competition through 1974 to the point that the Red Sox figured they’d had enough of the minors. The hot young prospects agreed, given how well they performed during the September call-up period at Boston. Given starting jobs to begin 1975, neither Lynn nor Rice would skip a beat facing major league pitching, resulting in one of the most memorable dual-rookie performances the game has ever seen.

BTW: In their brief time at Boston after being called up at the end of 1974, Lynn batted .419 with two homers, two doubles, two triples and 10 RBIs in 43 at-bats, while Rice hit .269 with a homer and 13 RBIs in 67 at-bats.

Boston rookies Fred Lynn (left) and Jim Rice sparked the Red Sox and finished 1-3, respectively, in the AL MVP count. (Associated Press)

By the end of the year Lynn’s name had reached household status, and he became the first player to win both AL Most Valuable Player and Rookie of the Year honors at once with a .331 batting average, 21 homers and 105 RBIs. Additionally, his work in center field earned him a Gold Glove to round out his résumé as a total top-notch package.

Rice quietly emerged in Lynn’s shadow as very much his equal. His power was already something of a talk—he would once break a bat checking his swing—but he was also a loyal student of Ted Williams’ hitting techniques, which helped make him a complete batter as his .309 average, 22 homers and 102 RBIs in 1975 would attest. In the AL MVP vote, Rice would finish third behind Lynn and Kansas City’s John Mayberry.

Boston’s everyday lineup featured plenty of youthful promise beyond the star rookie duo, including Dwight Evans (23 years old), Cecil Cooper (25) and Carlton Fisk (27), a burly brawler of a catcher who hit .331 after missing the first two months with a broken arm suffered during spring training. On the mound, three veteran starters kept the Red Sox well balanced; Rick Wise (29) humbly led Boston with 19 wins; Bill Lee (28), named Spaceman for his loony yet sharp, arid dry wit that threw sportswriters off-balance, added a stellar 17-9 record; and there was Luis Tiant, the flamboyant 34-year-old Cuban with his trademark 180-degree pitching delivery. Tiant’s 18-14 record was continued proof of his success as a reclamation project after his arm was considered dead four years earlier.

BTW: Wise did well to overcome his trivia question stigma of being traded one-up for Steve Carlton four years earlier.

The Rise and Fall of El Tiante

Luis Tiant’s rollercoaster career ride took him from a stunning 1968 star turn to the minors in 1971—and back to the top with the Red Sox in the early 1970s.

With everything more solidly in place, the Red Sox managed to accomplish in 1975 what they could not do in 1974—hold off a furious late-season rally from the Baltimore Orioles to win the AL East. But they paid a price; Jim Rice busted his hand a week before the regular season wrapped, reducing his postseason status to that of a spectator.

The Red Sox wouldn’t need Rice in the ALCS against the Oakland A’s, who with a 98-64 record remained strong despite the free agent loss of Catfish Hunter. But Boston impressively put an end to Oakland’s turbulent three-year championship ride, steamrolling the A’s in three straight games.

Even a healthy Rice wouldn’t sway prognosticators into giving Boston any hope against their World Series opponent: The Cincinnati Reds.

It had been a good 20 years since anyone in the National League looked as awesome and complete as Sparky Anderson’s Big Red Machine. No one could stop them. Not the defending NL champ Los Angeles Dodgers, who finished second—a very distant second, by 20 full games—to the Reds in the NL West. Not the Pittsburgh Pirates, the NL East champion who had none of Cincinnati’s conglomerate power and were rudely swept away by the Reds in the NLCS.

BTW: By the percentages, the Reds’ 108-54 record was the best since the 1953 Brooklyn Dodgers.

Weakness was not in the Reds’ vocabulary for 1975; there was none to speak of. They were potent, leading the NL in runs scored. They were fast, stealing a league-high 168 bases in 204 attempts—an 82% success rate then unsurpassed in major league history. They were flawless, committing fewer errors than any other team in the majors—at one point going 15 straight games without a single gaffe to set another all-time mark. They were staunch, with a solid if not dominant starting rotation finishing last in complete games (22) backed up by a strong bullpen leading the league with 50 saves. They were unbeatable at home, notching a NL record 64-17 mark in the friendly, often-filled confines of Riverfront Stadium.

BTW: This was mostly by design from Sparky Anderson, who earned the nickname “Captain Hook” for his rash habit of removing his starters.

It’s hard to believe that the Reds began this great campaign at 18-19, but that’s where they were on May 17. So Sparky Anderson decided to discard starting third baseman John Vukovich—a misfiring piston in the Big Red Machine—and moved Pete Rose from the outfield to replace him. Always the gamer, Rose accepted the challenge and excelled at playing a position for which he had little experience. The move also opened up Rose’s left-field spot for a flowering young talent named George Foster. Everything suddenly clicked; the Reds won 43 of their next 53 games, capped off by a 10-game win streak at the All-Star break, and spent the rest of the summer in cruise control to take the NL West. Rose batted .319 with 210 hits and a league-high 112 runs playing mostly at third; Foster hit .300 with 23 homers and 78 RBIs.

For six innings, Game One of the 1975 World Series became a tense case of which starting pitcher would crack first—Boston’s Luis Tiant or the Reds’ Don Gullett, one of three 15-game winners in the Cincinnati rotation. Gullett finally gave in during the seventh, thanks in part to Tiant—whose leadoff single ignited a six-run rally. That was more than enough for Tiant, who wrapped up a five-hit shutout at Fenway.

BTW: Gullett would have won more had the oft-injured hurler not been limited to 22 starts.

The Red Sox looked ready to take Game Two as well when they took a 2-1 lead into the ninth—but lost it. Dave Concepcion’s two-out infield single brought home Johnny Bench with the tying run, and then Concepcion himself scored the winner on a Ken Griffey double.

It was Boston’s turn to play comeback in Game Three at Cincinnati, but controversy—in the name of backup Reds outfielder Ed Armbrister—got in the way. After Dwight Evans tied it in the ninth with a two-run homer, the Reds attempted to answer in the 10th with a leadoff single by Cesar Geronimo. Asked to bunt, Armbrister laid one down in front of the plate—and bumped into Carlton Fisk, scrambling from behind the plate to field the ball. Distracted—and interfered with, as Fisk would soon loudly argue—Fisk wildly threw past second in an attempt to force Geronimo, who moved onto third, and then home as the winning run when Joe Morgan singled three batters later. As Geronimo scored, an angry Fisk flung his catcher’s mask against the backstop.

After Tiant labored through 163 pitches to reroute the Red Sox back on track with a 5-4 Game Four triumph, the Reds took Game Five, 6-2, as another Cuban native, Cincinnati slugger Tony Perez, homered twice after going hitless in his first 15 Series at-bats.

Rain—lots of it—greeted the two teams back in Boston with the Reds just one win away from wrapping it up. Game Six sat waiting for four straight days as the uncooperative weather kept the tarps unfurled over the Fenway turf.

It would be worth the wait.

Fred Lynn immediately powered the Red Sox ahead in the first inning with a three-run homer, and it remained 3-0 until the Reds’ fifth, when Lynn violently crashed against the center-field wall trying to make another sensational catch off the bat of Griffey—who ended up at third with a two-run triple before scoring the tying run on a Bench single. A two-run double by George Foster put Cincinnati ahead in the seventh, and Geronimo’s solo home run in the eighth pushed the Reds further up at 6-3.

Boston quickly started to answer in the bottom of the eighth by putting the first two runners on, but top NL reliever Rawly Eastwick came in and just as quickly retired the first two batters he faced. But he had less luck with the third batter. Bernie Carbo, a one-time rising star for the Reds who was now pulling part-time duty in Boston, clubbed his second pinch-hit home run of the Series to even the score.

BTW: Years later, Carbo claimed that he was high on marijuana when he launched the home run.

The Red Sox seemed a lock to win in the ninth when, with nobody out, they loaded the bases. But Lynn popped out to short left—and third-base runner Denny Doyle, believing he had heard third base coach Don Zimmer yell, “Go! Go! Go!” to him, tagged up and took off. A stunned Zimmer later told Doyle he was actually shouting, “No! No! No!” Doyle was out at home by a mile. The Reds next got a ground out to escape into extra innings.

The emotional roller coaster ride continued past the ninth. Joe Morgan sent a deep fly towards the right-field wall in the Cincinnati 11th, but Evans caught the ball with a half-leap against the waist-high fence. An incredulous Griffey, running from first convinced he was going to score an easy go-ahead run, was doubled off.

Hitless through the 10th and 11th innings, the Red Sox led off the 12th with Fisk. After taking one pitch, Fisk next launched a high fly down the left-field line. Hopping towards first, Fisk waived his arms toward first base, as if frantically trying to will the ball from going foul. If telekinesis was a factor, it paid off by the barest of margins. Fisk’s ball struck high off the foul pole—an ironic name, since any ball that hits it is fair—and Fisk’s arms went from a right turn to straight up in celebration. The Red Sox forced a Game Seven with what is arguably heralded as the greatest baseball game ever played.

Pete Rose puts everything into a head-first slide at third base on Joe Morgan’s ninth-inning single that brought home the game- and World Series-winning run in Game Seven at Boston. (Associated Press)

Somehow, the Reds absorbed the emotional sting of the loss and remained confident going into the winner-take-all affair at Fenway. Even after the Red Sox took a 3-0 lead off a wild Gullett in the third, they stayed focused, determined that their moment would come.

That moment came in the sixth. With two outs, Boston starter Bill Lee threw a blooping curve for which he coined the name “Leephus,” and Tony Perez smashed it over everything—Yaz, the Green Monster, the netting above—for a two-run homer. An inning later, Pete Rose singled in the game-tying run and, in the ninth, Morgan looped one in front of Lynn to bring Griffey home with the go-ahead tally. The strong Cincinnati bullpen, which had allowed only a hit since relieving Gullett in the fifth, retired the Sox in order in the ninth to give the Reds their first World Series triumph since 1940.

BTW: The Leephus was a moderate variation of the famed Eephus pitch used by Rip Sewell in the 1940s…The Reds were outscored by Boston 30-29—the fourth time in five years a Series winner scored fewer runs than the loser.

The baseball boom—in the form of rising attendance, a healthier balance of hitting and pitching, and the sense that the sport was developing a contemporary chic—would not begin to take full flower until 1977. But the seeds for baseball’s national renewal were undoubtedly sewn in 1975 with a World Series few will ever forget.

Forward to 1976: The Big Leaguer Emancipated Shackled for nearly a century, major leaguers are freed with the death of the reserve clause.

Forward to 1976: The Big Leaguer Emancipated Shackled for nearly a century, major leaguers are freed with the death of the reserve clause.

Back to 1974: “I’m Just Glad It’s Over” Hank Aaron’s long and personally painful ride to home run history comes to a successful conclusion.

Back to 1974: “I’m Just Glad It’s Over” Hank Aaron’s long and personally painful ride to home run history comes to a successful conclusion.

1975 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1975 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1975 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1975 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1970s: Power to the Player Curt Flood’s sacrificial stand to win free agency opens the door for the biggest challenge yet to the reserve clause, which is eventually shattered—but not without fans suffering from numerous player strikes and holdouts.

The 1970s: Power to the Player Curt Flood’s sacrificial stand to win free agency opens the door for the biggest challenge yet to the reserve clause, which is eventually shattered—but not without fans suffering from numerous player strikes and holdouts.

Marty Appel recalls his time with the New York Yankees during the 1960s and 1970s—and being one of the few people to work for George Steinbrenner and not get fired.

Marty Appel recalls his time with the New York Yankees during the 1960s and 1970s—and being one of the few people to work for George Steinbrenner and not get fired.