THE YEARLY READER

1976: The Big Leaguer Emancipated

After a century of being enslaved by the reserve clause, major leaguers are given their freedom in the form of modern-day free agency. For better of for worse, the game will never be the same.

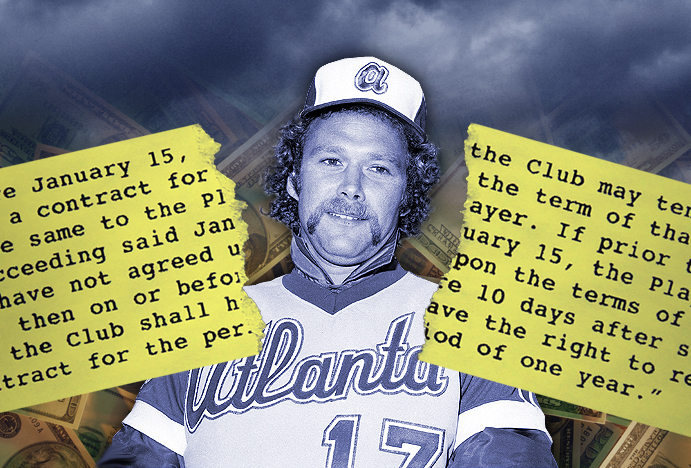

Andy Messersmith became the first major leaguer to successfully rip apart baseball’s suppressive reserve clause, signing a lucrative seven-figure deal with the Atlanta Braves and ushering in the era of modern free agents. (Associated Press)

To the owners of baseball, it was the Holy Grail. To the players, it was the Devil Within.

And by 1976, it would be dead and buried.

The reserve clause was a short and, for the owners, very sweet passage of language first adopted in 1879 by the National League to bring fiscal stability to the game at the expense of the players. The clause gave major league teams the perpetual power to shackle their players from signing with other teams at will, a rampant practice that had caused the collapse of whole teams if not whole leagues.

There was no players union to fight it, and the resulting imbalance of power enraged ballplayers. They revolted in 1890 by forming their own circuit, the Players League, to try and regain the upper hand, but it became a one-year wonder that drowned in a sea of red ink due to low capital and high legal costs confronting the other leagues in court.

For the next 85 years, the reserve clause reigned supreme over major league players; the 1922 antitrust exemption given to baseball only strengthened the owners’ legal position on the matter. But when Marvin Miller became head of the fledgling Major League Baseball Players’ Association in the late 1960s, he closely studied the clause’s language and spotted a weakness in its long-standing claim to perpetuity. To Miller, the clause read that a team signing a player did reserve the right to re-sign him for the next year—but if that player went unsigned through that second, “option” season, he would become a free agent at the end of that year.

It was as if the reserve clause had gone unread since the 19th Century. When word of Miller’s interpretation reached the owners, they grew nervous—because they felt Miller had uncovered a valid challenge to the clause.

The owners could have met Miller halfway or better on the clause and negotiated a deal to neuter its power while retaining a majority of control in the game, but they instead made three critical mistakes through the early 1970s that would forever haunt them.

The first mistake was to inexplicably give away crucial leverage by allowing an independent arbitrator to rule on player grievances—including any challenge to the reserve clause. The second mistake was to hire as that arbitrator Peter Seitz, a stately 70-year-old man who relished poetry and, somehow unbeknownst to the owners, backed basketball star Rick Barry in his successful attempt to defeat an NBA reserve clause word for word that of baseball’s. The third mistake would be the owners’ continued, addictive arrogance of playing hardball at contract time—which in 1975 led to two unsigned pitchers, Andy Messersmith and Dave McNally, to play out their option years and give Miller the ammunition he needed to take his case to Seitz.

BTW: The Los Angeles Dodgers refused Messersmith a no-trade clause request; McNally, traded to Montreal for 1975, played unsigned after the Expos allegedly broke an oral commitment to pay him $250,000 over two years.

In November 1975, Seitz heard the arguments. The union reiterated their take on the reserve clause language. Commissioner Bowie Kuhn, testifying for the owners, said if the clause fell, so would the sky; half of all major league teams would go bankrupt, he warned. In the end, Seitz pleaded with both sides to negotiate rather than be forced to make a decision. When the owners refused, Seitz gave his edict—deciding for the players and slaying the century-old reserve clause as everyone knew it.

The owners reacted with scorched-earth vehemence. They fired Seitz, appealed the ruling to the Federal courts (where they were rebuffed), locked out the players at spring training to muscle up for approaching labor negotiations with the union, and refused to bid on Andy Messersmith. That was, until iconoclastic new Atlanta owner Ted Turner waived off the other lords and signed Messersmith to a three-year, $1.75 million deal—making him the first true modern free agent.

BTW: The risks of signing lucrative multi-year free agent contracts were exposed with Messersmith; arm problems limited him to 18 wins from 1976-79 before retirement at age 34. As for Dave McNally, he retired halfway through 1975 and did not make himself available on the free agent market.

One team that certainly didn’t need to go to the open market and sign Messersmith—or anyone else—was the Cincinnati Reds.

Fresh off of one fantastic championship campaign, the Reds embarked on another that would be among the most dominant in history. Cincinnati led the NL in every major offensive category, from batting average to extra base hits to runs to stolen bases—usually by a wide margin. It could have been worse for opponents; the Reds set a NL season record for most runners left on base.

Second baseman Joe Morgan remained the central spark for the Big Red Machine, echoing the team’s offensive dominance by doing it all. He batted .320 with 27 home runs, 111 runs batted in, 113 runs scored, 114 walks and 60 stolen bases while being caught only nine times. Add a fourth straight Gold Glove on defense and Morgan walked away with his second NL Most Valuable Player award in as many years.

Four other everyday Cincinnati players hit over .300, including left fielder George Foster (.306 average, 29 home runs, 121 RBIs), who finished second in the MVP vote; Pete Rose (.323 average with 215 hits and 130 runs), who finished fourth; and right fielder Ken Griffey, who at .336 finished a close second to Bill Madlock in the NL batting race.

The Reds first showed the second-place Dodgers who was boss in the NL West, winning 13 of 18 games from Los Angeles on their way to a 10-game first-place finish and 102-60 record. They then showed the talented yet overmatched and inexperienced NL East champion Philadelphia Phillies who was boss at the NLCS with an impressive three-game sweep.

It’s All Red at the Top

Few if any teams have ever displayed an offense so completely dominant as the 1976 Reds, who led in every single category.

With the World Series, the Reds were now going to show a self-described boss from New York who was the true boss in all of baseball.

But for the moment, it was quite possible that Yankees owner George Steinbrenner would be content with just getting to the Fall Classic.

A boisterous and demanding shipping magnate from Cleveland, Steinbrenner had bought the Yankees three years earlier from CBS, which for 10 years had transformed the fabled franchise into just another major league team while actually losing money on its investment. Steinbrenner’s driven personality led many to believe that a Yankee revival was on the way—yet at his introductory press conference, a mild-mannered Steinbrenner insisted he would be an absentee owner and entrust the business of baseball to his front office. Such words elicited disbelief from those who worked for him with his previous sports toy, a semipro basketball outfit named the Cleveland Pipers. With the Pipers, Steinbrenner stormed into the locker room to chew the team out after losses, refused to pay players if they didn’t win, and then threatened to fire them if they complained about it to the press.

BTW: Steinbrenner purchased the Yankees for $10 million, some $3 million less than CBS paid with considerably more worthy 1964 dollars.

It didn’t take long for Steinbrenner to practice micromanagement over absenteeism in New York. The turnover rate in the Yankees’ front office was of a head-spinning frequency; those who weren’t fired by the temperamental Steinbrenner fled on their own volition to a saner working environment. Ralph Houk, the veteran Yankees manager with ties to the pre-CBS glory days, saw enough of Steinbrenner and quit after one year with him. Bill Virdon, Houk’s successor, lasted less than two years.

BTW: Decades later, Houk said that virulent Yankees fans were as much to blame as Steinbrenner.

Steinbrenner’s third manager would give birth to one of baseball’s great love-hate working relationships.

It had been 15 years since Billy Martin had last played in the majors, but his disposition had hardly aged with grace. He had become a prominent manager with the same intense, hard-nosed attitude that sometimes reached below the belt. Unfortunately, that attitude didn’t stop with his opponents. In Martin’s managerial stints at Minnesota, Detroit and Texas, the results were similar: Taking sub-.500 teams and instantly turning them into winners—and just as instantly wearing out his welcome, getting fired after scuffling with anyone and everyone, from traveling secretaries to marshmallow salesmen to his own players.

Martin bragged that he was no “yes man,” which must have left Yankee employees bracing for impact when Steinbrenner brought him on in late 1975. But despite what he might had heard about Steinbrenner, Martin always considered himself a Yankee and savored the opportunity to don pinstripes for the first time since 1957.

In his first full season managing the Yankees in 1976, Martin gave the usual performance with an upsurge in team performance, and all was well with the Yankee world—for now. Martin remade the team roster during the offseason and produced a series of trades, all of which worked in New York’s favor.

Building the Bridge, Then Burning It

Billy Martin wore out his welcome with the teams he managed as fast as he built them out of mediocrity. Here’s the good and bad of Martin’s three managerial tours of duty prior to joining the Yankees in 1976.

Among the new Yankees were starting pitchers Ed Figueroa (19-10, 3.01 earned run average) and Doc Ellis (17-8, 3.18), outfielder Mickey Rivers (.312 average, 43 stolen bases) and second baseman Willie Randolph (.267 average, 37 steals). Added with veterans in catcher Thurman Munson (.302, 17 home runs, 105 RBIs), first baseman Chris Chambliss (.293, 17, 96) and third baseman Graig Nettles—who hit 11 of his AL-leading 32 homers in the month of April—the Yankees played consistent winning baseball all year, never seriously challenged in the AL East as they were welcomed back to a rebuilt Yankee Stadium after two years paying rent at Shea Stadium.

BTW: Despite having a home of their own again, the Yankees played much better on the road (52-27) than they did at Yankee Stadium (45-35).

Pairing off against the Yankees in the ALCS were the Kansas City Royals, who under Whitey Herzog—another feisty manager in his first full year—were a group of young, speedy, line drive-crazy athletes perfectly built to excel on the vast and fast artificial turf at Royals Stadium. Having finally ended the Oakland A’s five-year reign at the top of the AL West, the Royals were sure not to be taken lightly by the Yankees, who lost seven of 12 regular season games to Kansas City.

Even after playing rotten baseball in September—and without the services of star outfielder Amos Otis—the Royals gave Martin’s Yankees everything they had. It came down to a thrilling, decisive fifth game in which the Yankees, after blowing a three-run lead in the eighth inning via a George Brett blast into Yankee Stadium’s upper deck, recovered with a leadoff, first-pitch solo shot by Chris Chambliss in the ninth that sent the fans into a state of utter delirium.

BTW: Chambliss, desperately trying to complete his winning home run trot amid scores of invading Yankee fans, was brought out half-dressed after the game to touch third base and home to make the 7-6 score official.

Chris Chambliss secures the Yankees’ first AL pennant in 12 years with a walk-off home run—but crazed, celebratory New York fans, in virtual mob mode, storm the field and practically assault him before he reaches home plate. (Associated Press)

The Yankee euphoria would be stopped cold by the Red-hot Cincinnati nine at the World Series; even an uncharacteristically deflated Martin conceded, after his team was roundly swept in four games, that the Yankees had been beaten by one of the greatest teams in baseball history as the Reds became the first ballclub to sweep both the LCS and Fall Classic.

The Reds were powered by those who neither collected MVP votes nor hit over .300 during the year. Catcher Johnny Bench, whose off-field domestic problems affected his play and plunged his average to .234 with just 16 home runs, came alive with a .533 (8-for-15) batting average and a pair of homers. Dan Driessen, a part-time .247 hitter, took advantage of the designated hitter role in the first Series to allow it, and hit .357 with two doubles and a homer. And the Cincinnati pitching staff, again the solid collection of no-name hurlers, silenced New York bats by allowing a .222 average and only eight runs.

BTW: For the entire postseason, Bench hit .444 with two doubles, a triple, three home runs and seven RBIs.

The first full free agent market opened for business after the 1976 World Series. In an agreement between management and players, a special draft would be held in which each team could pick up to 12 free agents, from which they could sign two. Only one team declined to participate: The Cincinnati Reds, defiantly believing they were above leaning upon free agency to maintain a championship level of baseball they had displayed over back-to-back seasons.

George Steinbrenner, on the other hand, embraced free agency and sensed the immediate impact it could bring to a franchise. And so he reached deep into his pocketbook to begin building the best team money could buy.

Forward to 1977: Reggie! Reggie! Reggie! Reggie Jackson caps a stormy first year in New York with a storybook flourish for the Yankees at the World Series.

Forward to 1977: Reggie! Reggie! Reggie! Reggie Jackson caps a stormy first year in New York with a storybook flourish for the Yankees at the World Series.

Back to 1975: Birth of a Renaissance America’s passion for baseball is re-awakened with, arguably, the greatest World Series ever between Boston and Cincinnati.

Back to 1975: Birth of a Renaissance America’s passion for baseball is re-awakened with, arguably, the greatest World Series ever between Boston and Cincinnati.

1976 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1976 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1976 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1976 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1970s: Power to the Player Curt Flood’s sacrificial stand to win free agency opens the door for the biggest challenge yet to the reserve clause, which is eventually shattered—but not without fans suffering from numerous player strikes and holdouts.

The 1970s: Power to the Player Curt Flood’s sacrificial stand to win free agency opens the door for the biggest challenge yet to the reserve clause, which is eventually shattered—but not without fans suffering from numerous player strikes and holdouts.

Mark Littell talks about his claim to infamy, serving up Chris Chambliss’ pennant-winning home run in 1976—and his current venture selling cutting-edge protective cups for athletes.

Mark Littell talks about his claim to infamy, serving up Chris Chambliss’ pennant-winning home run in 1976—and his current venture selling cutting-edge protective cups for athletes.