THE YEARLY READER

1981: No Ball, One Strike

A crippling players strike divides the season into two as owners adopt a split-season format with increased playoff participants. Purists are enraged, as are several teams whose first-rate records somehow fail to qualify them for the postseason.

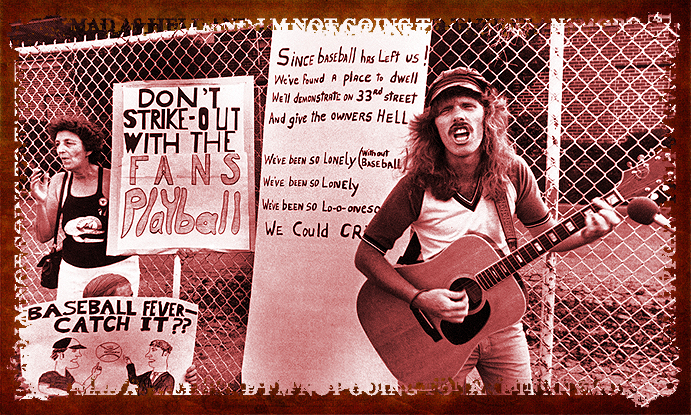

Angry fans in Baltimore voice their displeasure over baseball’s midseason player strike, which lasted 50 days, canceled 713 games and split the season in half. (Associated Press)

This time, it was war.

For 15 years, the Major League Baseball Players Association—under the tactful leadership of Marvin Miller—had developed credibility, a deeply unified self-reliance and a combative relationship with baseball owners, who struggled to adapt to a stronger union after years of iron-fisted rule. The union’s emergence produced a level playing field at negotiation time which usually resulted in the occasional spring training walkout or lockout—relative small arms skirmishes that, only once in 1972, spilled into the regular season, and then just for a week.

But by 1981, negotiations to wrap up a new Basic Agreement had soured to the point that the union decided to go for the jugular. The players threatened to strike, as always, but not to force cancellation of a few meaningless exhibitions; instead, their plan was to strike at the heart of the regular season, to derail it in high gear rather than trip it up at the starting gate.

Lasting 50 days and wiping out a third of the regular season, the 1981 strike—and its resulting side effects—would create one of the game’s most unpleasant, if not strangest, years on record.

Only one issue needed settling to avoid a work stoppage, but it was a heavyweight: Free agent compensation. Since the mandatory erasure of the reserve clause five years earlier, player salaries under free agency hadn’t merely gone up; they’d spiked into orbit. Arbitration provided a good dose of the afterburner fuel. The players were in no hurry to alter this new frontier, but the owners—who believed their once powerful leverage over the players had been skyjacked—would try something, anything, to bring the hyperinflation under control…and perhaps break the union as well.

Both sides drew a line as wide and deep as the Grand Canyon. With abundant rainy-day reserves stocked on both sides, labor war was inevitable.

Thus, the 1981 season began with a dark squall line descending upon it. Fans feared the excitement of the season’s first few months would likely get invalidated with a season-ending walkout, like a well-played game forever washed away by rain before the fifth inning.

On the field, enthusiasm was everywhere. It was in New York, where ex-San Diego superstar Dave Winfield debuted for the Yankees under a record contract for George Steinbrenner. It was in Oakland, where new A’s owner Walter Haas unchained the franchise from the derelict final years of Charles Finley’s tenure, and was packing them in at the Coliseum with the help of a record-setting 11-0 start under manager Billy Martin. And it was in Philadelphia, where Pete Rose was closing in on Stan Musial’s all-time National League career hit record for the defending champion Phillies.

BTW: Winfield smashed a record with a 10-year deal worth $15 million—a figure that would likely swell to $23 million thanks to a yearly cost-of-living clause that allowed the numbers to rise with inflation.

But the biggest news of early 1981—outside of the imminent strike—was the stunning overnight success of Fernando Valenzuela, a portly 20-year-old Mexican pitcher who came to Los Angeles literally with the dirt-poor clothes on his back.

After watching Valenzuela relieve 10 games late in 1980 for the Dodgers—allowing no runs in 17.2 innings—Los Angeles manager Tommy Lasorda seriously considered giving Valenzuela his first career start in the one-game NL West playoff against the Houston Astros. Lasorda didn’t, the Dodgers lost, and—using 1981 hindsight—wished he had.

Valenzuela was given the Opening Day start when veteran Jerry Reuss pulled a muscle. Relying on a screwball that dumbfounded opposing hitters, the left-handed Valenzuela shut down those same Astros, 2-0, and launched himself on an electrifying start in which he won his first eight games—all complete games, five by shutout—with a staggering earned run average of 0.50. A man of little expression who spoke no English, Valenzuela seemed oblivious to the phenomenon known as Fernandomania, taking North America and especially Los Angeles, with its substantial Latino population, by storm. It provided a gold mine of pure, inexpensive PR for the Dodgers, who drew 2.4 million fans in 1981—a figure that might had been closer to four million had a third of the season not been lost.

Valenzuela’s sensational early-season pitching would later prove critical for the Dodgers, who led the NL West by a half-game over Cincinnati on June 12—the day the players walked.

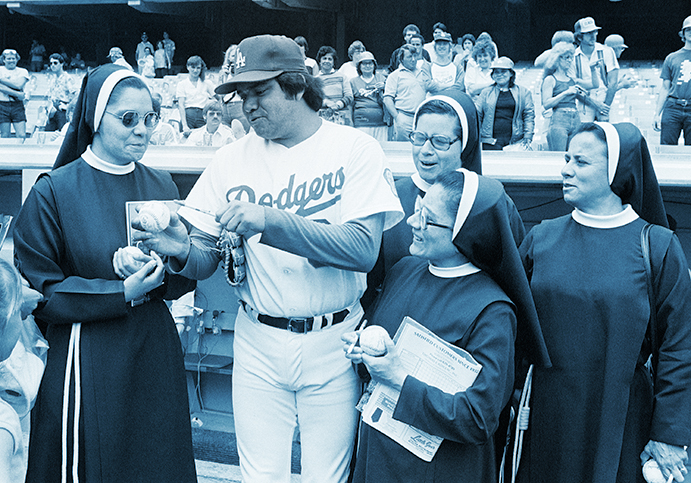

Even Catholic nuns took notice of Los Angeles rookie sensation Fernando Valenzuela, who captivated the nation with his blazing start until the strike put everything on hold. (Associated Press)

Fernandomaniac

Fernando Valenzuela began 1981 as if no one could touch him. Here’s a breakdown of his first eight starts, all of them complete game victories—five by shutout—and how he managed for the rest of the season.

Bargaining sessions between the players and management had grown so contentious, it was a wonder they were talking at all. A vicious hatred had developed between the lead negotiators on both sides: Marvin Miller, backed as always by an impressive show of player unity, and owner rep Ray Grebey, hired by management hawks for his past role in taming the unions at General Electric. Federal mediator Ken Moffett finally threw his hands up in the air and told both sides to go away, cool off, and come back in a week. At one point Marvin Miller threw out a trial balloon to the press that players would form their own league and begin play in 1982.

Miller knew the owners would hang tough so long as their war chest—in the form of a $44 million Lloyd’s of London insurance policy—didn’t dry up. So Miller kept his players patient, not an easy chore despite the union’s intense solidarity, and even less easier once a gag order was placed on both sides in mid-July, leaving many players restless as they struggled to get news from their union reps. The owners suffered internal tensions as well, with the usual factions developing between hard-liners and those on the more dovish end.

As the Lloyd’s account balance neared zero, the owners were the first to break a sweat and begin bending in negotiations. Progress was made, and on July 31, the two sides had a deal. There would be free agent compensation for the owners, but it would be minimal enough to keep the whole free agency concept solvent in the players’ eyes.

BTW: The deal allowed for each team to protect a minimum of 24 players from their 40-man roster for compensation; as an incentive to keep teams from signing free agents, any that didn’t would be allowed to protect more.

The players had won again, but only in principle. Negotiated victory had cost them $28 million in salaries. The owners, meanwhile, lost $72 million—$116 million before insurance. Yet as always, it was the fans—stripped of the game for two months and with no say in the matter—who were ultimately the biggest losers.

Ten days after the All-Star Game reactivated the season on August 9, baseball announced an expanded, unique—and highly assailed—playoff structure that would be a departure from anything before it and, thankfully, since. The regular season would officially be split into two halves: One before the strike, the other after, each consisting of roughly 55 games per team. The postseason would commence with divisional series pitting the first- and second-half winners from each division against one another, with the winners moving on to the standard league championship series. Intended to kick start interest by virtually giving every team a fresh start, the split-season idea would prove highly imperfect.

BTW: If the same team won both halves of the season, they would face the team with the next best overall divisional record. This scenario never played out.

The four divisional winners of the first half—the Phillies, Dodgers, Yankees and A’s—awkwardly found themselves playing proverbial lame ducks through the second half, with nothing to gain or lose. As expected, neither of these teams played to the level of intensity or success they had exhibited in the first half, with little angst to fret over—except in New York, where a typically impatient George Steinbrenner fired manager Gene Michael just four weeks shy of the postseason.

Three teams would expose the warts of the split-season concept with huge embarrassment. The Cincinnati Reds sported the majors’ best overall record at 66-42—but because they finished a close second in the NL West during both halves of the season, failed to qualify for the enlarged postseason. Same thing for the St. Louis Cardinals, whose 59-43 mark—best in the NL East—was split into two second-place finishes and tee time in October. On the other side of Missouri—and the other side of fortune—lay the Kansas City Royals, placing first in the AL West for the season’s second half after an abysmal 20-30 showing in the first half. At 50-53 overall, the Royals became the only team in major league history to reach the playoffs with a losing record—and quickly proved their worth by going three and out against the A’s in their divisional playoff matchup.

Angry Red (And Redbird) Planet

By the percentages, the Cincinnati Reds and St. Louis Cardinals had, respectively, the first- and third-best record in the majors—but failed to qualify for the expanded postseason because neither failed to place first in either of baseball’s strike-induced “half- seasons,” finishing a close second each time.

The drama contained within the other three divisional playoffs—the first of its kind—showed that the split-season concept wasn’t all bad. The Yankees, now under once-and-current manager Bob Lemon, sweated out a tough five-game set with a spirited and talented Milwaukee Brewers ballclub that owned a better overall regular season record. In the NL, the Dodgers lost the first two games at Houston but took the series by winning the next three at Los Angeles behind great pitching that limited the Astros to just six runs in five games. And the Montreal Expos—making their first and only postseason appearance in 36 years before moving to Washington in 2005—denied the Phillies a chance to repeat as champions by taking a five-game, seesaw affair—clinched with a six-hit shutout thrown by Steve Rogers over Steve Carlton at Philadelphia.

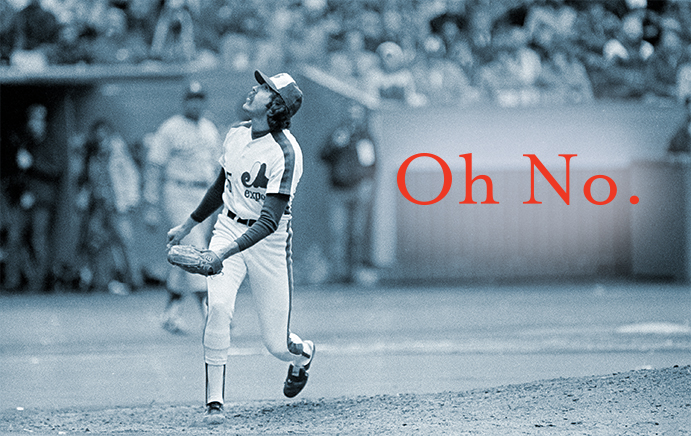

Advancing on, the Dodgers and Expos continued their dramatics at the NLCS by taking the series to the deciding fifth game at Montreal. Fernandomania had been quelled by the strike and a more mortal second half performance by Valenzuela, but the rookie phenom stayed sharp as the Game Five starter at Olympic Stadium, keeping the Expos in blank check after allowing a single first-inning run. For Los Angeles it would be TGIM—Thank God it’s Monday—as in veteran Rick Monday, who on a Monday delivered the game, series and pennant for Valenzuela and the Dodgers with a memorable ninth-inning, two-out solo shot to win, 2-1.

BTW: Monday’s home run came against Steve Rogers, pitching rare relief in place of starter Ray Burris, who pitched eight solid innings.

Montreal pitcher Steve Rogers watches Rick Monday’s deep fly ball go over his head, on its way to clearing the fence to put the Dodgers ahead to stay in the ninth inning of the decisive NLCS Game Five. Monday’s shot put an end to the Expos’ only playoff appearance in 36 years at Montreal. (Associated Press)

It was much ado about nothing at the ALCS, and that was quite a shame considering the contestants: The Yankees against Billy Martin and the A’s. The fiery, twice-over ex-New York manager couldn’t fire up his youthful squad, which quickly got dismissed in three by an aggregate score of 20-4. In typical Yankee fashion, the team celebrated by fighting one another: Reggie Jackson and Graig Nettles exchanged blows at a postgame party when the two fought over a chair Mrs. Nettles had temporarily vacated.

The Dodgers, trying to shake off four straight World Series losses—the last two against the Yankees—began to wonder if they were becoming baseball’s bridesmaids of Brooklyn once more. Advancing to the 1981 Fall Classic, manager Tommy Lasorda already got half of a long-sought after wish: A chance for revenge against the Yankees.

Lasorda would be granted the other half of his wish—fulfilling that revenge—with mirror-imaged precision.

After losing the first two games at Yankee Stadium, the Dodgers came home and won the next three over the Yankees, then coasted in Game Six back at New York to take the series. It was as if someone had taken the results of the Dodgers’ last Series appearance against the Yankees in 1978 and simply swapped teams with the results. No matter, the Dodgers would take it anyway they could, even if it was somewhat ugly—and it was, clawing back through six errors to win Games Three, Four and Five at home by a single run each.

BTW: Davey Lopes made four of those six errors, and committed six errors overall—a World Series record for a second baseman.

The Los Angeles triumph would be a swan song of sorts, knowing that age and aches were about to tear their roster apart in the coming off-season. This even applied to the long-standing Dodgers infield of Steve Garvey, Davey Lopes, Bill Russell and Ron Cey, wrapping up their ninth—and final—season together. Lopes would be traded to Oakland in 1982, Garvey and Cey would depart in 1983 via free agency, and Russell would fade to the bench by 1985.

Amid the Dodgers’ victory, George Steinbrenner stole the show. It was tough enough for the New York owner to watch his team fall apart after winning the first two Series games. Tough enough to watch Yankees reliever George Frazier lose three games, tying the Series record held by Lefty Williams—whose clandestine duty was to lose games for the 1919 Chicago Black Sox. Tough enough to watch his high-priced pet Dave Winfield, finishing a regular season with numbers resembling more those of Tony Lazzeri than Lou Gehrig, and now evoking Roger Repoz in the postseason with a miserable .182 (10-for-55) average, no home runs and three RBIs in 14 games.

So the Baron of the Bronx took out his anger—first in a Los Angeles hotel elevator where he allegedly got into it with some Dodgers fans who otherwise were never seen or heard from, and then after the Series when he publicly apologized to New York City and “Yankee fans everywhere” for his team’s loss.

BTW: Baltimore Orioles owner Edward Bennett Williams on Steinbrenner’s alleged elevator scuffle: “This is the first time a millionaire hit someone and had not been sued.”

If comedy was Steinbrenner’s intention, then he succeeded in putting smiles on the faces of baseball fans—a rare sight in a year otherwise scorned upon.

Forward to 1982: Streaking Engagement There’s hardly a dull moment in a year where baseball’s playoff contenders careen about like out-of-control rollercoasters.

Forward to 1982: Streaking Engagement There’s hardly a dull moment in a year where baseball’s playoff contenders careen about like out-of-control rollercoasters.

Back to 1980: Finally Philly After nearly a century of trying, the Philadelphia Phillies finally reach the championship podium.

Back to 1980: Finally Philly After nearly a century of trying, the Philadelphia Phillies finally reach the championship podium.

1981 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1981 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1981 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1981 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1980s: Corporate Makeover Baseball enjoys a healthy boom on several fronts, with increased attendance, corporate sponsorship and memorabilia sales; players also continue to enjoy skyrocketing salaries, but some abuse their newfound riches by delving into illegal drugs.

The 1980s: Corporate Makeover Baseball enjoys a healthy boom on several fronts, with increased attendance, corporate sponsorship and memorabilia sales; players also continue to enjoy skyrocketing salaries, but some abuse their newfound riches by delving into illegal drugs.