THE YEARLY READER

1988: Roy Hobbs In Dodger Blue

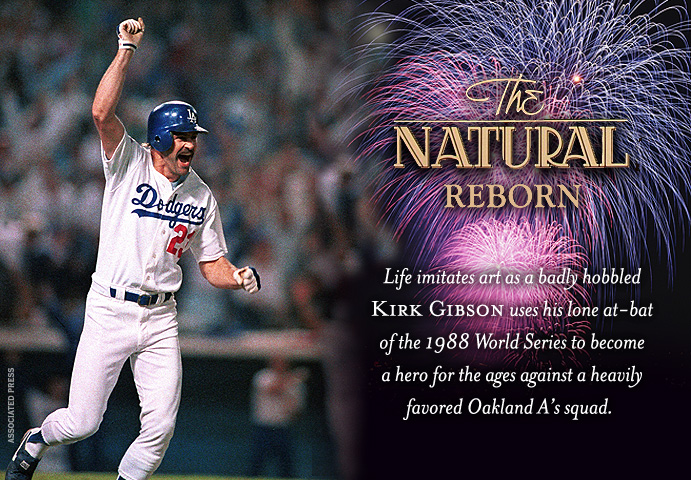

The Los Angeles Dodgers send up a hobbled wreck of a player in Kirk Gibson during the first game of the World Series—and against Oakland relief ace Dennis Eckersley proceeds to deliver one of baseball’s most memorable moments.

By appearance only, Kirk Gibson was never to be confused with Roy Hobbs, the fictional hero of The Natural. His gruff and scruffy exterior provided a stark contrast to the pretty-boy charisma of Robert Redford’s Hobbs.

But in the opening game of the 1988 World Series, Gibson suddenly found a lot in common with Hobbs. All but crippled, Gibson limped to the plate with the game on the line and belted one of baseball’s most memorable home runs off its most dominant reliever of the day, giving the Los Angeles Dodgers a major jolt of momentum that helped slay the heavily favored Oakland Athletics.

There were only two differences between Gibson’s heroics and the storybook ending to The Natural. One, the light towers were spared. Two, it was pure nonfiction.

In the four years prior to 1988, Gibson had been a remarkable, gritty constant for the Detroit Tigers, his teammates inspired by his all-out, hard-hat work ethic. Gibson tried free agency once after 1985, but found only one taker: The incumbent Tigers. Later discovered to be a victim of collusion, Gibson was given his immediate freedom after 1987.

The Dodgers gave him a new home for $4.5 million over three years, but not before Gibson allowed the Tigers a shot at re-signing him for less. Detroit owner Tom Monaghan declined and whipped up anti-Gibson fury in the Motor City, labeling his former star as a ruffle-haired has-been decaying into a part-time designated hitter.

Upon arriving at Florida for his first spring camp with the Dodgers, Gibson was appalled to see a team coming off consecutive 73-89 campaigns clowning about like a careless band of pranksters. And when Gibson became the butt of one of their jokes—putting on his cap and later discovering, too late, that it had eyeblack garnished all around the inside—he angrily split from Dodgertown, black halo and all, hours before the team’s first exhibition.

BTW: Dodgers reliever Jesse Orosco was the culprit.

Despite the desperate pleas of manager Tommy Lasorda—who fostered the Dodgers’ fun-loving environment—Gibson confronted his teammates the next day and laid down the gauntlet. He told them that winning, and only winning, was fun, and that he was ready to sacrifice himself for the team—and demanded the same of them.

Gibson’s intense sermon made the Dodgers realize how wayward their souls had become, and they quickly warmed to their new spiritual leader. The pranks stopped. Players played hurt. The Dodgers’ 0-1 record after Opening Day would mark their only placement below the .500 mark all season long. They quickly snared first place in the National League West and stayed there for the balance of the year.

If Gibson was the Dodgers’ heart, ace pitcher Orel Hershiser provided the muscle. A tall, slender redhead who resembled Howdy Doody, Hershiser was hardly intimidating to his teammates; but with a beady-eyed, almost soulless stare and an aggressive pitching game, he definitely put a hook into the minds of opposing batters.

Through August, Hershiser was enjoying a Cy Young Award-caliber season. He was merely warming up. Starting in Montreal on August 30, Hershiser went on an amazing tear, pitching one shutout after another while closing in on the all-time record of 58.2 consecutive scoreless innings set 20 years earlier by former Dodger Don Drysdale. Doubt was cast over whether Hershiser had enough innings available in the season’s waning weeks to surpass the mark, but he got his chance when, in his final regular season start at San Diego, he pitched the 10th inning of a scoreless game and broke Drysdale’s mark by a single out.

BTW: Drysdale watched every one of Hershiser’s 59 consecutive scoreless innings from the broadcast booth as a Dodgers announcer.

Hershiser’s final numbers—a 23-8 record, eight shutouts and a 2.26 earned run average—were elite figures within an exceptional Dodgers pitching staff flourishing both in the rotation and in the bullpen, and clearly provided the backbone for a offense that, minus Gibson’s .290 batting average, 25 homers, 76 runs batted in and 31 steals (in 35 attempts), was weighed down with an anemic supporting cast. But somehow they scored when they needed to; the Dodgers batted .201 over their last 33 games, yet managed to win 20 of them.

Orel Report

Beginning with the fifth inning of his August 30 start at Montreal, Orel Hershiser pitched the rest of the season—59 innings worth—without allowing a single run.

The Dodgers entered the NLCS as considerable underdogs to the NL-East winning New York Mets, revived two years after a world championship with 100 wins—10 of them coming against the Dodgers in 11 tries—and a pitching staff every bit the Dodgers’ equal.

The Mets got Hershiser to bend—rendering him mortal with two runs in Game One—but completely broke closer Jay Howell, who single-handedly turned what could have been a 3-0 series lead for the Dodgers into a 2-1 lead for the Mets. Howell blew Hershiser’s lead and the save in Game One, and in Game Three—attempting to hold another lead for Hershiser—was caught with pine tar on his glove, an illegal act. Alejandro Pena was rushed in for the ejected Howell on a cold and wet New York afternoon and quickly got shelled for five runs to ruin another Dodgers would-be victory.

BTW: The Dodgers claimed Howell’s intent was not to cheat, but he ultimately had to serve a two-game suspension.

Fed up with leaving anything to chance, the two Dodgers stars—Hershiser and Gibson—took over and rescued the series when it appeared lost. Gibson hit a 12th inning, tie-breaking solo shot in Game Four, saved by Hershiser when, with nobody left in the Los Angeles bullpen, he came in to record the final out. Gibson’s crucial three-run homer in Game Five secured a 7-4 win, and after losing Game Six, 5-1, the Dodgers were righted by Hershiser, throwing a five-hit, 5-0 shutout in Game Seven to secure the NL pennant.

Overcoming the underdog label against the Mets, the Dodgers now encountered an even bigger hurdle at the World Series in the Oakland Athletics.

Eight years after pulling the A’s out of the decrepit final years of the Charles Finley era, new owner (and denim jeans magnate) Walter Haas spared no expense to aggressively market the franchise and put rear ends back in the uninhabited seats of the Oakland Coliseum. But by 1988, the A’s acquired the best advertising money could buy with a bona fide powerhouse under the leadership of Tony La Russa, much happier in Oakland after his previous existence piloting the Chicago White Sox.

Jose Canseco (right) celebrates with fellow “Bash Brother” Mark McGwire after launching an ALCS home run against the Red Sox at Boston. The 24-year-old Canseco made good on a preseason vow to amass 40 homers and 40 stolen bases during the season. (Associated Press)

Everywhere you looked, the A’s were without weakness. They had pitching: Their rotation was anchored by Dave Stewart, a struggling major league vagabond until he discovered the forkball in Oakland and transformed into a constant 20-game winner. They had relief: Dennis Eckersley, another reclamation project who overcame alcohol abuse and a ‘has-been’ label with a remarkable conversion from starter to closer, leaving him clean, sober and untouchable to opposing batters. They had defense: First-year shortstop Walt Weiss’ non-stop acrobatics made him the third straight AL Rookie of the Year wearing an Oakland uniform.

And they had hitting. Powering their offense was Mark McGwire and Jose Canseco—two awesome, muscular sluggers whose tape-measure home runs earned them the name “Bash Brothers.” McGwire, a year after smashing the rookie home run mark with 49, cooled off in 1988 with a still-respectable 32 homers and 99 RBIs. Canseco, whose first two years were loaded with home run power at the cost of mediocre batting averages and a ton of strikeouts, made good on a brash spring training promise and became the first major leaguer to hit 40 homers and steal 40 bases in one year. Added with 120 runs scored, an AL-high 124 RBIs and, finally, a healthy .307 average, Canseco’s numbers made him an easy choice for AL Most Valuable Player.

While Oakland dominated the AL West with a 104-58 record—the defending world champion Minnesota Twins (91-71) actually had a better record than 1987, but were no match for the thundering A’s—the Boston Red Sox squeaked by at 89-73 to take the East. After finishing the season’s first half at .500, the Red Sox fired manager John McNamara and brought in Joe Morgan—no, not the Hall-of-Fame second baseman, but the lifetime .193 hitter for five teams over four years in the early 1960s. His major league career as manager would become instantly more memorable, leading the Red Sox to 19 wins over his first 20 games and, later, a razor-thin first-place finish by a game over Detroit and two each over Milwaukee and Toronto.

BTW: Morgan said he received autograph requests in the mail from those mistaking him for his more popular namesake—and signed them anyway.

The Red Sox were cast as sacrificial lambs for the A’s at the ALCS, and they played the part well. Oakland slaughtered the Red Sox in four games with seven home runs—including three from Canseco—stingy pitching that limited the potent Boston offense to 11 runs, and flawless relief from Dennis Eckersley, who saved all four victories in the A’s sweep.

BTW: In the first murmurs of baseball’s coming performance enhancement epidemic, Red Sox fans at Fenway Park taunted Canseco with chants of “Ster-oids!”

If the Red Sox were considered pushovers for the A’s, then the Los Angeles Dodgers might as well have not counted. And if the A’s had enough to salivate about on the eve of the World Series, their confidence mushroomed with news from Los Angeles: Kirk Gibson was done. On top of various aches and pains accumulated through the regular season, Gibson had badly beaten up both his legs during the NLCS and was considered highly doubtful for the Fall Classic.

Game One at Los Angeles looked to be a made-to-order triumph for the A’s. Canseco hit a grand slam, Dave Stewart pitched eight strong innings, and terrific defense by the A’s snuffed out one Dodgers rally after another. The A’s took a 4-3 lead to the bottom of the ninth, and Dennis Eckersley looked ready to lock down the win against a feeble lineup of Dodgers hitters.

Kirk Gibson, watching the game on TV, couldn’t stand it anymore. A prisoner of his own clubhouse with his legs wrapped in ice, Gibson had to do something, anything. He tore off the ice packs, got on his uniform and headed to the batting cage; he then sent the clubhouse attendant to the dugout with a message for Tommy Lasorda: “I’m available.”

Eckersley gunned down the first two batters with ease and then lost Mike Davis to a walk, though he felt quite secure in his chances with the man on deck, Dave Anderson—a powerless utility player also beat up by injury. Little did Eckersley, the A’s—and most Dodgers players, for that matter—realized what Lasorda had up his sleeve.

Gibson emerged from the clubhouse and limped straight to the plate representing the winning run. At first Gibson looked like he didn’t have a chance against Eckersley, barely fouling off the first two pitches and teetering about on his legs after each swing like a newborn deer. But Gibson hung tough, fighting off two more foul balls while drawing the count full. At that moment, Gibson remembered what advance scout Mel Didier had told him: On 3-2, Eckersley will go with the backdoor slider.

And that’s exactly what Gibson got.

With all his painful might, Gibson reached out over the plate and pulled it to right field, high, deep—and out—well into the crowded bleachers. Dodger Stadium went nuts, and Gibson ended the only remaining suspense when he successfully hobbled around the bases.

If ever one swing of the bat killed the momentum of a baseball team, Gibson’s did it to the A’s. Emotionally comatose from the shock of Game One, the A’s never recovered. Only in Game Three did they manage to eke out a victory when Mark McGwire hit a walk-off solo shot for a 2-1 result, but outside of that blast and Canseco’s grand slam, the Bash Brothers were a combined 0-for-34 at the plate. Without Gibson the rest of the way, the Dodgers were hardly sluggers themselves—but managed to snare the key hits in the clutch with a lineup that included traditional no-name bench warmers in Mickey Hatcher, Jeff Hamilton and John Shelby, and major underachievers (and former A’s) in Davis and Alfredo Griffin, both of whom hit under .200 during the regular season.

Then there was Hershiser. The Dodgers ace remained exceptional, throwing a three-hit shutout in Game Two and a complete game, 5-2 victory in the Game Five clincher—all the while matching Gibson’s 1.000 series batting average with a single and two doubles in three at-bats.

All or (Mostly) Nothing

Jose Canseco hit a grand slam in Game One of the World Series, and Mark McGwire’s walk-off solo shot won Game Three. But outside of those two blasts, the Bash Brothers were reduced to ash by the Dodgers.

Injuries would get the better of Kirk Gibson over the final two years of his contract, sidelining him for 91 and 73 games in 1989 and 1990, respectively. But the Dodgers had long since received their money’s worth with Gibson’s one and only, historic World Series at-bat in 1988 when, in a fleeting moment of pulp nonfiction on an October evening at Chavez Ravine, Roy Hobbs was alive and well and playing for the Los Angeles Dodgers.

Forward to 1989: Of Triumph and Tragedy In the glow of its renaissance, baseball gets burned by a series of unwanted events.

Forward to 1989: Of Triumph and Tragedy In the glow of its renaissance, baseball gets burned by a series of unwanted events.

Back to 1987: Dome Sweet Dome The young and feisty Minnesota Twins lose 50 games away from home, but thank God for the Metrodome.

Back to 1987: Dome Sweet Dome The young and feisty Minnesota Twins lose 50 games away from home, but thank God for the Metrodome.

1988 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1988 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1988 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1988 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1980s: Corporate Makeover Baseball enjoys a healthy boom on several fronts, with increased attendance, corporate sponsorship and memorabilia sales; players also continue to enjoy skyrocketing salaries, but some abuse their newfound riches by delving into illegal drugs.

The 1980s: Corporate Makeover Baseball enjoys a healthy boom on several fronts, with increased attendance, corporate sponsorship and memorabilia sales; players also continue to enjoy skyrocketing salaries, but some abuse their newfound riches by delving into illegal drugs.

Steve Sax discusses his infamous mental block at second base, his role in Kirk Gibson’s legendary World Series home run and his stint on The Simpsons.

Steve Sax discusses his infamous mental block at second base, his role in Kirk Gibson’s legendary World Series home run and his stint on The Simpsons.