THE YEARLY READER

1994: The Year That Should’ve Been

A bitter and vastly unpopular player strike shuts down the season in August—bringing an early, cruel end to the wonderful campaigns of Tony Gwynn, Matt Williams, the Cleveland Indians and Montreal Expos. Worst of all: The World Series is canceled for the first time in 90 years.

Imagine a single, magical baseball season in which Ted Williams hits .406, Roger Maris clubs 61 home runs, and the Miracle Mets of New York win the World Series.

Now imagine if that season is killed off halfway through, stripped of the Fall Classic and all its grand achievements—to be forever lost in the tomb of unknown milestones.

Welcome to 1994.

For over two decades, baseball fans had grown used to the occasional work stoppage, like powerless villagers enduring chronic border skirmishes between two neighboring, warring countries. In instances like 1981, when a sizeable chunk of the season got chewed away by a player strike, the labor conflict had flared into all-out war.

In 1994, it would be Armageddon.

On the field, baseball was on the threshold of a great era. Flashy superstars such as Ken Griffey Jr., Frank Thomas, Barry Bonds and Jeff Bagwell were electrifying fans. Attendance was booming. Beautiful new ballparks were opening. Offense wasn’t merely on the rise; it was exploding, with long-standing records in danger of falling. And barring injury, Cal Ripken Jr. was now just a year away from replacing Lou Gehrig as the man who played the most consecutive games in history.

But off the field, there was trouble in paradise. Player salaries continued their skyrocketing pace. The lavish television deal with CBS was coming to an end with nothing comparable in sight to feed the kitty. The gap between rich team, poor team was widening like never before.

And a new labor agreement needed to be negotiated.

Major league owners had grown as mad as hell and weren’t going to take it anymore. They had basically gotten the short end of the stick in every labor battle against the players’ union since Marvin Miller brought it to prominence. The owners often had themselves to blame, their unity frequently crumbling while player solidarity remained remarkably airtight. Baseball’s commissioners were often no help, butting in and settling a strike for the good of the game and their image—but seldom in the Lords’ best interests.

The owners quickly solved one problem by neutering the duties of the commissioner into a man of no importance, a powerless figurehead who couldn’t nose in on labor negotiations. (That “interim” commissioner Bud Selig was an owner himself made the issue, in the interim, a moot one.) Solving their second problem—dealing with one another on labor strategies—only served to reinforce the fleeting state of owner solidarity. For over a year the owners fought amongst each other over the idea of revenue sharing, with the haves and have-nots taking opposite sides of the issue. They finally hammered something out, albeit reluctantly, in early 1994.

The easy part was done; now the owners had to present their revenue sharing plan—one that would be tied to slightly lower free agent eligibility, the elimination of salary arbitration and, most boldly, the introduction of a salary cap—to the players’ union as negotiations began on a new labor agreement.

Now in charge of the union was 44-year-old Donald Fehr, whose baby-faced, ashen façade seemed incapable of displaying a sense of humor—though when he was handed the owners’ proposal in June 1994, he didn’t know whether to laugh or cry foul. The salary cap, in particular, was fighting words to Fehr and the players; they had seen what a cap had done for the NBA and NFL and wanted no part of it. The union tossed the owners’ proposal into the trash as if it was junk mail.

Progress was not a buzzword as negotiations struggled on. Plain and simple, the owners were adamant on a salary cap; the union was equally opposed. Neither side made things easy away from the bargaining table. The players decided to set a strike date of August 12—much earlier than expected—leaving little time for what little chance there was for compromise. The owners responded by withdrawing a scheduled $7.8 million payment to the players’ pension fund, which served little purpose except to tick the union off.

Late on a cool Oakland evening on August 11, the A’s Ernie Young went after a high fastball from Seattle’s Randy Johnson and missed. It was the final pitch of the Mariners’ 8-1 victory.

And it was the last pitch thrown in 1994.

The players made good on their threat and began striking the next day. Baseball’s evolving, dreamlike season on the field had been overrun by the nightmare taking place off it. That any season would be canceled was shameful enough; that it had to be this one, with an endless menu of astounding individual feats and sentimental team favorites on the rise, was almost unpardonable.

Matt Williams of the San Francisco Giants and the Mariners’ Ken Griffey Jr. were mounting the greatest assault yet on Roger Maris’ 33-year-old season home run record. With 43 blasts already in the statbook, Williams was right on pace to match Maris at 61; Griffey, with 40, wasn’t far behind. Neither was Houston’s Jeff Bagwell (39), the Chicago White Sox’ Frank Thomas (38) or the Giants’ Barry Bonds (37). With the competition crowded and baseballs routinely soaring high and deep as if every game was played in the thin air of Denver, Maris’ 61 suddenly looked like a mortal number in danger of being erased from the record book. We’ll never know.

BTW: Six players were easily on pace to hit 50 homers—an eye-opening feat, considering only two players had reached 50 in the previous 29 years.

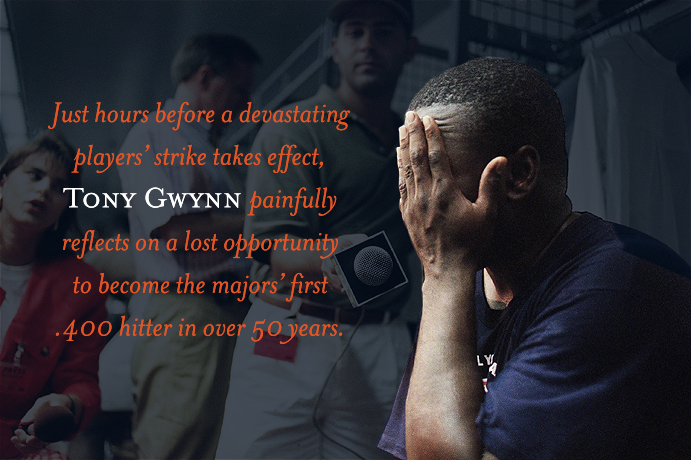

Not Quite Four Out of Ten

Tony Gwynn’s strike-shortened .394 batting average is the highest recorded since Ted Williams eclipsed the .400 mark in 1941. Below is the list of top 10 player averages, headlined by Gwynn, since Williams hit .406.

Tony Gwynn, the San Diego Padres’ perennial .300 hitter and then some, was making a serious run at .400. He was batting .394 when the games stopped on August 12, but he hit .439 over his last 14 games and, as he would later recall, “Everything was rolling.” Gwynn might have been baseball’s first .400 hitter in 53 years. We’ll never know.

Overall, hitters were partying like it was 1929, with a fast accrual of prodigious numbers not seen since the days of Hack Wilson and Jimmie Foxx. Though the season had stopped with each team playing roughly 115 games, more than a few players had racked up enough numbers that would have looked stunning over 162. Five players had already knocked in 100 runs, with Bagwell and Minnesota’s Kirby Puckett on pace for at least 160. Frank Thomas, batting a healthy .353, was on pace for over 150 runs and 150 walks. Earl Webb’s 1931 record of 67 doubles was being seriously challenged by not one but three players—Chuck Knoblauch, Larry Walker and Craig Biggio, each of whom already had over 40. The White Sox’ Lance Johnson had a shot at 20 triples. Cleveland’s Kenny Lofton was closing in on 100 steals. All of the records and magic numbers were approachable. We’ll never know.

BTW: Bagwell’s phenomenal season—he also hit a whopping .368—would have ended regardless of whether the players walked or not; he suffered a broken bone in his hand after being hit by a pitch just two days before the strike.

The year’s top baseball stories, between the lines, were not limited to the singular exploits of superstars. A number of long-suffering teams were capturing the imagination of baseball fans, old and new alike.

The Cleveland Indians had won nothing since 1954. Nothing. In the past 29 years, they had recorded only four finishes above the .500 mark—and in each case, barely. Sports Illustrated suffered a delusional epiphany in 1987 and predicted the Indians would reach the World Series. The Tribe lost 101 games instead. The idea of a Cleveland pennant was reduced to comical Hollywood fantasy, recalled in the 1989 movie Major League.

After years of throwing away promising talent through bad trades or now-or-never gambles that failed, the Indians wisely built themselves back on their feet and became a potential powerhouse on the rise—just in time to escape aging, monstrous Cleveland Stadium for downtown and cozy, modern Jacobs Field. There was newfound excitement at “The Jake,” and it wasn’t just urban renewal; the Indians’ winning surge was just as responsible for packing them in. The Tribe’s impressive roster included peak performers in Albert Belle and Kenny Lofton, rising talents in Jim Thome and Manny Ramirez, and over-the-hill stars Eddie Murray, Dennis Martinez and Jack Morris, each of whom had plenty of gas left in the tank.

Cleveland won early and often and engaged in a two-way battle with the White Sox within the American League’s newly-formed Central Division. Though the season ended short with the Indians trailing the Sox by a single game, they held solid command of the AL Wild Card spot—another new invention for 1994. Silenced from postseason play ever since Willie Mays caught up to Vic Wertz’s monster drive 40 years earlier, the Indians had a chance to finally sound off in October. We’ll never know.

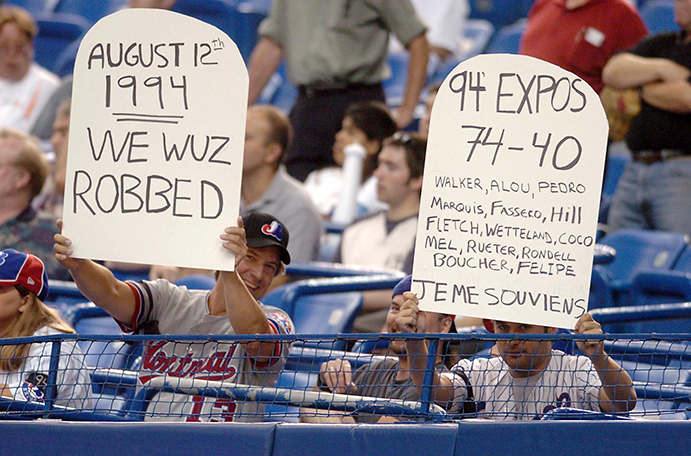

There was also excitement north of the border in Montreal, where the low-budget Expos were defying the modern-day convention of baseball economics and running away with the majors’ best record at 74-40. The game’s most inexpensive roster was also its youngest—all but a few Expos were over 30—and featured a who’s who of current and, mostly, future stars: Larry Walker, Pedro Martinez, Moises Alou, Marquis Grissom, Ken Hill, Jeff Fassero, John Wetteland and Jeff Shaw.

Montreal’s success was used as an argument against revenue sharing from several circles—including George Steinbrenner, owner of the re-emerging New York Yankees (fielding the AL’s best record at 70-43), spouting of how easy it was for the financially challenged Expos to thrive in baseball’s current economic system. It was an analysis high in fault. Short-term success was not the Expos’ problem; retainment of their rising stars was. Maybe Steinbrenner could afford a dynasty, but the Expos couldn’t; the 1994 season gave Montreal its big chance to dance as baseball’s Cinderella before the clock struck midnight—and its roster became too expensive to keep. We’ll never know.

BTW: In 1995, with Walker, Grissom, Hill and Wetteland gone, the Expos finished last in the NL East; Wetteland would became the 1996 World Series MVP—for Steinbrenner’s Yankees.

Few cities suffered the sting of the strike more than Montreal, where the low-budget Expos were fielding the majors’ best record. The ripple effects of a stolen season north of the border became painfully evident 10 years later when the Expos left for Washington. (Associated Press)

The strike saved baseball from a few embarrassments in the realigned—and depleted—four-team AL West. The Texas Rangers, at 52-62, led the division on the day the players walked. And the Mariners, a few games back, were spared the indignity of playing the final two months on the road after falling ceiling tiles inside the Kingdome had rendered the facility indefinitely unsafe.

As August wandered into September with no hope of a settlement in sight, the owners—led by Bud Selig—decided on September 9 to pull the plug on the 1994 season, rationalizing that any deal struck afterward would have come too late to salvage the campaign. Twenty-five other owners agreed. Two did not: Cincinnati’s Marge Schott, because, among other reasons, her Reds were leading the NL Central; and Baltimore’s Peter Angelos, not only because he was losing abundant Camden Yards revenue, but because the strike was impeding on Cal Ripken’s bid to break Lou Gehrig’s consecutive games mark.

BTW: As in 1981, the first-place Reds were jobbed by a strike that cost them a chance to play in the postseason.

Selig’s decision wasn’t so much a backbreaker as it was a formality. There was no chance that baseball would resume anytime soon. As the two negotiating sides stood militant against one another—even the owners, fiercely determined not to lose this labor war, were sticking together for a change—the acrimony was at an all-time high. The fans mounted the usual pitchfork rebellion to get the warring sides’ attention, but the expected deaf ear was turned; there was just too much money and honor at stake to give the fans’ wrath the time of day.

The World Series had been played for 90 straight years, through high times and lean times, through scandal, catastrophe and world war. But for the first time since John McGraw and John Brush told the infant American League to get lost in 1904, the Fall Classic was going to be thrown away by more trivial obstacles such as greed and mistrust.

Some sense was knocked into the owners at year’s end when they replaced their chief negotiator, Richard Ratvich—whose relationship with Don Fehr was incendiary at best—with two owners fielding less combative personalities: Boston’s John Herrington and Colorado’s Jerry McMorris. Some calm had returned to the negotiating table, but the owners were still adamant: No settlement without some kind of cap on player salaries. If the union continued to say no, the owners were ready to declare an impasse and implement their own labor rules, regardless of what the union had to say.

Armageddon had come, the world of baseball had blown itself up many times over, and nuclear winter was at hand; 1994 was dead.

The question now became: Could 1995 be saved?

Forward to 1995: Thanks to Cal, Hideo—and Sonia, Too Numerous feel-good moments rescue baseball from its most devastating work stoppage.

Forward to 1995: Thanks to Cal, Hideo—and Sonia, Too Numerous feel-good moments rescue baseball from its most devastating work stoppage.

Back to 1993: The Last Great Pennant Race On the eve of the wild card era, 100-game winners San Francisco and Atlanta fight it out for a single postseason spot.

Back to 1993: The Last Great Pennant Race On the eve of the wild card era, 100-game winners San Francisco and Atlanta fight it out for a single postseason spot.

1994 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1994 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1994 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1994 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1990s: To Hell and Back Relations between players and owners continue to deteriorate, bottoming out with a devastating mid-decade strike—souring relations with fans who, in some cases, turn their backs on the game for good. Recovery is made possible thanks to a series of popular record-breaking achievements by ‘class act’ stars.

The 1990s: To Hell and Back Relations between players and owners continue to deteriorate, bottoming out with a devastating mid-decade strike—souring relations with fans who, in some cases, turn their backs on the game for good. Recovery is made possible thanks to a series of popular record-breaking achievements by ‘class act’ stars.