THE YEARLY READER

2002: The Wild, Wild Card West

Neither the Anaheim Angels nor San Francisco Giants finish in first place, but they catch fire in the postseason as wild card entrants and engage in a rip-roaring World Series that goes the distance.

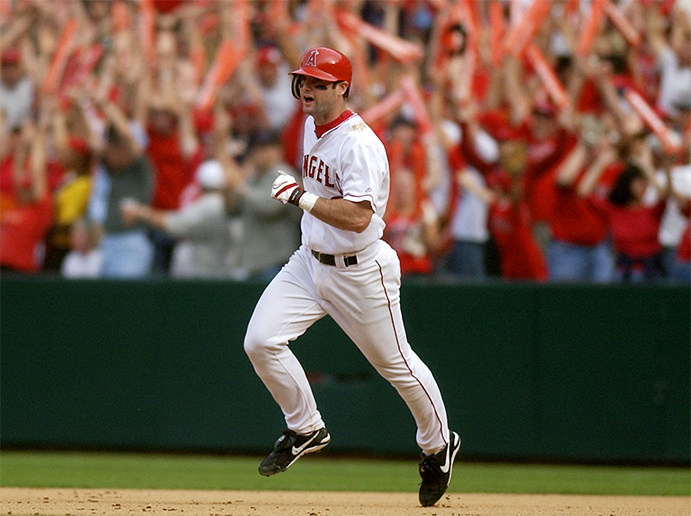

Dealt a burdening hand full of prime postseason opponents, the Anaheim Angels come up all aces by toppling fellow wild card foe San Francisco and superstar Barry Bonds in the World Series. (Associated Press)

The San Francisco Giants were eight outs away from winning their first World Series in 40 years.

Through a full century of World Series play, no team had led as late and as by much in a potential series clincher as the Giants in Game Six—and lost. Leading 5-0 in the bottom of the seventh, Giants manager Dusty Baker felt so confident about his team’s chances, when he went to the mound to visit an effective yet tired Russ Ortiz, he not only gave the starting pitcher the rest of the evening off—he gave him the ball to take home to his trophy case.

To the Anaheim Angels, staring angrily from their dugout, the interpretation of Baker’s gesture was crystal clear: Thanks, Russ, you helped us win the World Series.

Up to that moment, nothing seemed to have inspired the Angels back to life. Not the Rally Monkey, jumping insanely up and down on the JumboTron, nor the ear-shattering noise of ThunderStix being banged together by a boisterous home crowd heavily clad in Angels red. But the unusual gesture of Ortiz receiving the “game ball”—before the game was even over—was far more palpable to the Angels, transcending both chalkboard fodder and the psychological warfare of the team’s marketing department.

Reawakened, the Angels banged away at one Giants reliever after another for the next two innings, climaxing their Game Six comeback—and setting up a victorious Game Seven—when Troy Glaus doubled the eventual winning run off All-Star closer Robb Nen.

Much of the Angels’ story of 2002 began two years earlier with another comeback over Nen and the Giants. In a midseason interleague contest, the Angels had been trailing all evening to the Giants and, in a fit of total improvisation by the guys running the ballpark’s video board, a video clip of a monkey jumping up and down was slapped up on the screen with the words “Rally Monkey” flashing across it. This David Letterman-inspired variation to the clichéd exhorting of the fans to make “Noise!” may have initially drawn curious smiles from the 19,000 in attendance, but they were made believers when the Angels rallied with two ninth-inning runs off Nen to beat the Giants, 6-5.

An ensuing stretch of home games won in the clutch by the Angels made the Rally Monkey a celebrated Anaheim tradition, joining other, less popular Angels traditions: Their failure to win, let alone reach, a World Series since their 1961 inception; their ongoing status as common suburban cousins to the lordly Los Angeles Dodgers; and their constant falling apart under pressure, twice in the ALCS under traditional managerial choke Gene Mauch and, more than often, late in the regular season—most painfully in 1995, when they blew a 13-game lead to Seattle.

It appeared it would take far more than the Rally Monkey to lift the Angels to prominence. Anaheim lost 19 of its final 21 games in a 2001 campaign burdened with subpar performances from its normally reliable base of star hitters, including Tim Salmon and Darin Erstad. The Disney Corporation, which had lost $100 million on the Angels since buying the franchise in 1996 from original owner Gene Autry, was wanting out, thus making the Angels a topic of contraction gossip; one scenario had the team folding, to be replaced by the relocated Oakland A’s.

Breaking Down the Rally Monkey

Following the guidelines for use of the Rally Monkey—when the Angels are behind or tied in the sixth inning or later—here’s a detailed analysis of how much of a good luck charm the famed gimmick really was from its introduction in mid-2000 through the 2002 World Series.

The only upgrade for the Angels to start 2002 seemed to be aesthetic, as the team donned new, ironically devilish red uniforms. A 6-14 start, worst in franchise history to date, was an unwanted tonic for a seemingly wayward franchise. But the Angels suddenly made a startling u-turn and had their best May yet at 19-7—before catching even bigger fire for the summer. The Angels evolved into something so good, they managed to close the lead on the division-leading A’s even as Oakland was in the middle of an AL-record 20-game win streak, winning games on days the A’s had off; Anaheim kept the A’s sweating thereafter by winning 16 of 17 into September. But while the Angels could not ultimately overcome the A’s—still looking almighty at 103-59 minus the power of Jason Giambi, signed for gazillions with the New York Yankees—their 99-63 record easily and deservedly qualified them for the postseason via the AL wild card spot.

The Angels were a classic case of all 25 players coming together at once for third-year manager Mike Scioscia, a calm and collected presence who retained composure through the team’s rough start and a year-long batch of injuries that more than briefly sidelined slugger Tim Salmon, ace closer Troy Percival, veteran starter Aaron Sele, defensive standout catcher Bengie Molina and reckless center fielder Darin Erstad. But the most impressive element on the Anaheim roster was the previously unsung or untested within the team’s pitching staff. The rotation was unexpectedly led by three youngsters—Jarrod Washburn (18-6, 3.15 earned run average), Ramon Ortiz (15-9, 3.77), and John Lackey (9-4, 3.66 after a midseason call-up); the bullpen featured two tough-as-nails middle relievers (Brendan Donnelly and Ben Weber), self-described “vagabonds” who toiled in the minors until after turning 30.

The Yankees emerged from the regular season with baseball’s best record at 103-58, but they suffered the misfortune of getting paired up with the red-hot Angels in the postseason’s first round. Anaheim made the Yankees pay for sloppy pitching by hitting .376 with nine homers in a four-game upset of the four-time defending AL champions, whose departure was part of a defiant trend of underdogs prevailing in the first round. Besides the Yankees, the other favored nines ousted included the A’s, knocked out in five by the upstart, no-name Minnesota Twins—who would have been extinct through contraction had the courts not interceded; reigning world champion Arizona, swept away by the St. Louis Cardinals as they suffered without star slugger Luis Gonzalez, a separated shoulder victim one week before the playoffs; and the NL’s top seed in the Atlanta Braves, whose knack for postseason ineptitude continued with a five-game NLDS loss to baseball’s other meteoric wild card entry: The San Francisco Giants.

The Giants had much in common with the Angels beyond their wild card status, also suffering from recent season-ending disappointment: A hard-fought seven-game NLCS loss in 1987; a total shutdown at the earthquake-affected 1989 World Series; the failure to make the 1993 playoffs despite winning 103 games; bitter first-round departures in 1997 and 2000; and a 1998 defeat to the Chicago Cubs in a 163rd game to decide a wild card spot.

With one of the game’s more even-tempered owners in Peter Magowan, popular player manager Dusty Baker and an absolute jewel of a ballpark in Pac Bell Park, the Giants had become a top-notch destination for many major leaguers—as selected by one of the game’s best general managers in street-smart Brian Sabean. Yet emotional friction within the San Francisco organization was not absent. A rift had reportedly developed between Magowan and Baker—the former believing the latter had taken too much credit for the Giants’ success—leading to disbelief among Giants fans that the San Francisco future of Baker—in the final year of his contract—lay in doubt.

Definitely in doubt were the long-term prospects of Giants All-Star second baseman Jeff Kent. His mediocre start to 2002 was attributed to a spring training thumb fracture suffered while washing his truck, or so he claimed. Witnesses elsewhere described someone fitting Kent’s description wiping out on a motorcycle which, had he confessed to it, could have voided the final year of his contract. Any reporter who attempted to raise the issue to Kent—known for his blunt, cold relationship with the media—was walking on eggshells. The fisticuffs were saved for teammates when Kent, after getting into a dugout argument during a midseason game at San Diego, nearly came to blows with equally surly superstar Barry Bonds—finishing his tirade by reportedly shouting, “I want off this team!”

BTW: Many baseball contracts include clauses forbidding players from indulging in potentially unsafe recreational activities; Kent likely had one in his pact with the Giants.

Bonds had long since figured out the media and vice versa, so his tense disposition had become more Teflon-coated than Kent’s. His unbelievable play certainly didn’t hurt relations with Giants fans. An advance scout once said there were only four ways to pitch Bonds: Ball one, ball two, ball three and ball four. Pitchers took that advice more than ever in 2002, granting Bonds first base 198 times, 68 of them intentionally; both figures were all-time records previously shattered by Bonds himself, to be re-shattered by him over the next few years. When opponents had the guts to challenge, they usually lost; Bonds not only kept his power game going with 46 homers, he added his first-ever batting title by hitting a whopping .370. Combined with the walks, Bonds’ .582 on-base percentage easily surpassed Ted Williams’ long-standing mark.

With Kent recovering from all things physical and emotional to join Bonds in bashing the opposition through the season’s second half, the Giants emerged as the NL wild card by winning 25 of their final 33 games before toppling the Braves in the first round to advance to the NLCS, against the equally hot St. Louis Cardinals—which had taken 29 of their last 36.

The Cardinals’ hopes were riding not only on the bat of 22-year-old phenom Albert Pujols—who, like Eddie Murray 25 years earlier, jumped right in and started playing like an instant all-star—but also an emotional vow to win one for both pitcher Darryl Kile and long-time St. Louis broadcaster Jack Buck, both of whom had died within days of one another in June.

The Cardinals would win one—but unfortunately, just one—compared to the Giants’ four at the NLCS. The Giants crucially took the first two games at St. Louis, then closed out the series in San Francisco when they took Games Four and Five with late-inning heroics.

For all their clutch theatrics, the Giants still had nothing on the Rally Monkey.

After hitting seven home runs in 144 regular season games, Adam Kennedy belted four in the postseason—including three alone in ALCS Game Five to send the Angels to the World Series. (Associated Press)

The Angels began the ALCS with a split at Minnesota, where sellout Twins crowds dusted the cobwebs off the Homer Hankies and yelled with the same jet-engine resonance as they had during the 1987 and 1991 playoffs. But when the series moved on to Anaheim, the Twins discovered that their Metrodome faithful had finally met their match in noise pollution—taking the field to the combined roar of Angels fans and the ear-piercing ThunderStix they banged together.

BTW: The ThunderStix, first used in Korea in 1992, were large plastic inflated bats that, when banged together, made a loud, high-pitched noise.

Noises aside, all three ALCS games at Anaheim met the conditions to warrant the Rally Monkey’s appearance on the video board.

The Rally Monkey went 3-for-3.

Troy Glaus broke up a 1-1 tie in Game Three with an eighth-inning solo homer that stood as the Angels’ game-winner. Anaheim unlocked a seventh-inning scoreless tie in Game Four with seven runs to pull away, 7-1. And in Game Five, the Angels came to bat after the seventh-inning stretch trailing the Twins, 5-3—then responded with a 10-run avalanche of offense, highlighted with the last of three home runs hit on the day by lightweight second baseman Adam Kennedy, who had seven all year, to help claim the franchise’s first AL flag.

It didn’t take a rocket scientist for the Angels to figure out how to best beat the Giants in the World Series: Make sure Barry Bonds came up with the bases empty, and then avoid giving him anything good to hit. Historically, Bonds had been a postseason bust, batting .196 with a single homer in 27 career playoff games coming into 2002. But the Bonds of the new millennium was a different and far more dangerous hitter, as the Braves and Cardinals had already found out the hard way.

Finally Alive in October

Prior to 2002, Barry Bonds was labeled as a postseason choke—and the numbers clearly seemed to prove it. That all changed in a gargantuan way with Bonds’ 2002 playoff performance.

Through the first five games of the Fall Classic, the momentum shifted back and forth as two tenacious teams clouted away at inconsistent pitching that erred on the side of being awful. The Giants finally appeared to grab the driver’s seat with the finish line in sight after blitzing the Angels in Game Five, 16-4—and then tore out to a 5-0 lead in Game Six at Anaheim. Whether buoyed or not by the Rally Monkey—which already had come to the rescue once in the series, in Anaheim’s 11-10 Game Two triumph—the Angels made their improbable comeback after Russ Ortiz’s 6.2 innings of shutout ball, scoring three runs each in the seventh and eighth to win, 6-5, and pull even with the Giants to set up Game Seven.

San Francisco rested its winner-take-all hopes on starting pitcher Livan Hernandez, best remembered for his 1997 postseason heroics for the Florida Marlins. But it was obvious from the very first Anaheim batter he faced that Hernandez had nothing. That Dusty Baker left Hernandez in for even two innings—wildly allowing four hits, four walks and four runs—may have been the one excuse Peter Magowan needed to hand Baker a one-way ticket out of town.

Up 4-0, the Angels’ bullpen—so sharp during the regular season but, so far, a World Series dud—got its act together when it needed to and stifled the Giants following starter John Lackey’s five sufficient innings. Barry Bonds, who would be retired in only nine of 30 plate appearances throughout the series while slamming four tape-measure homers, never came to bat in Game Seven with a runner on base. The Giants lost, 4-1, and the Angels claimed their first world title in their 42-year history.

Eight years earlier, the concept of the wild card had chaffed at the emotions of baseball purists who believed the regular season would be rendered more meaningless with potentially inferior ballclubs sneaking in and finding destiny in a flash. Their argument was valid. But the 2002 season, one where each postseason participant won no fewer than 94 games, would not be the test case for the purists to cry bloody murder over the inclusion of backdoor entrants. Because, as the Anaheim Angels and San Francisco Giants showed, there were none.

Forward to 2003: Curses, Inc. Baseball’s two most famously cursed—the Chicago Cubs and Boston Red Sox—add to their long-suffering legend of heartbreak.

Forward to 2003: Curses, Inc. Baseball’s two most famously cursed—the Chicago Cubs and Boston Red Sox—add to their long-suffering legend of heartbreak.

Back to 2001: Raising Arizona The fourth-year Arizona Diamondbacks’ expensive fast track to the World Series reaches a successful conclusion.

Back to 2001: Raising Arizona The fourth-year Arizona Diamondbacks’ expensive fast track to the World Series reaches a successful conclusion.

2002 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 2002 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

2002 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 2002 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 2000s: Driven Deep to Disgrace The new century gives Major League Baseball a decidedly more international flavor with a healthy rise in foreign-born talent—but a disturbing pall is cast over the sport as one megastar after another is exposed for using steroids.

The 2000s: Driven Deep to Disgrace The new century gives Major League Baseball a decidedly more international flavor with a healthy rise in foreign-born talent—but a disturbing pall is cast over the sport as one megastar after another is exposed for using steroids.