The Ballparks

League Park

Cleveland, Ohio

(Cleveland Press Collection)

Rustic, tight and beloved with its cozy sightlines, unpredictable right field wall and a myriad of memorable moments, League Park lived to become the ballyard that wouldn’t go away. Not that anyone complained, as Clevelanders developed a soft spot for the little fellow that has stood the test of time and survived in one form or another all the way to the present day..

In the summer of 2014, a rebirth took place some two miles east of downtown Cleveland. Politicians, poets, young children and seniors old enough to remember back to the days of Bob Feller and Earl Averill gathered on a beautiful afternoon to officially christen the reopening of League Park after decades of neglect. Still standing from eons gone by was the old ticket office, which once looked orphaned against the back of the more industrial, steel-and-concrete ballpark structure, and a block-long remnant of the west side brick wall that looked as fragile as a Roman-era ruin. Beyond that, the spruced-up property has the look of your typical modern recreational park: Architecturally and botanically pleasing, with meandering paths dotted with benches and splash fountains rising from a circular area painted as a baseball.

Above all, the baseball field remains, and it’s faithful to the League Park of old: A spacious plot of land in left-center and a short poke down the right field line, guarded out to right-center by a tall fence separating the (now fake) turf from Lexington Avenue, just like it used to. For the more eclectic purists, the new fence includes the steel posts that jut out and, when directly contacted, can ricochet a baseball any which way. So when the little leaguers, high schoolers, weekend warriors and other ballplayers using the new League Park try to predict the carom, they’ll know how the right fielders, the center fielders and, on occasion, even the left fielders from generations earlier felt trying to chase the ball down.

At the plate, former Cleveland Indians slugger Travis Hafner was given the honor of being the first to swing away in the new facility. As Joe Jackson, Babe Ruth and countless other players who performed at League Park showed ages earlier, he made the park look small—planting 10 long flies over the tall fence and hopefully sparing the windows across the street at the Fatima Family Center.

Just Follow the Trolley.

The first hacks at League Park, 123 years earlier, were made responsible by one Frank DeHaas Robison. A local streetcar magnate, Robison started up an American Association team in 1887 and moved it to the National League two years later. He was never wild about the ballpark he initially set up shop in—a place that also happened to be called League Park—and his lack of enthusiasm for the joint deepened in 1890 when lightning did serious damage to it. The “aw, shucks” moment gave Robison an out to seek a new location; he found his ideal spot at the corner of Linwood Avenue and East 66th Street. Why so ideal? It just happened to be situated along one of his trolley routes. The vision of a financial win-win was too good to pass up and, by 1891, Robison had a new League Park of his own.

Aesthetically, there was nothing special about the pre-steel-and-concrete existence of League Park. Made of wood like most 19th Century parks, the ballpark consisted of a single, basic grandstand fronted on the outside by a modest, homespun entrance. The playing field offered more adventure; like Philadelphia’s Baker Bowl and Brooklyn’s Ebbets Field in later years, League Park was situated into a rectangular urban block that created a spacious left field—it was nearly 400 feet down the line—but a more cozy right field that measured a mere 290 to the pole. Not helping matters were several residences and a saloon that refused to sell in order to expand the ballpark property.

Other homes not in the way but within sight of spectators were happy to have their roofs painted in big, bold white letters promoting a local clothier, Bennet & Fish—which didn’t think to offer a free suit to any hitter who reached it with a home run. Had the promotion existed and the homes stuck around into the 1930s, über-slugger Jimmie Foxx would have collected; several players recall him bashing a monster drive not just over the left-field bleachers but also a small pasture behind it, estimating the shot at 600 feet. Beyond those few eyewitness accounts, no documented evidence of the home run exists—who knows, maybe it was just batting practice—but if they were right, it certainly was the longest ride a baseball ever took at League Park.

League Park debuted before a capacity crowd of over 9,000 on May 1, 1891 with the Spiders—as Robison’s team was then branded—romping over the Cincinnati Reds, 12-3. The winning pitcher that day was a 24-year-old right-hander from Gilmore, Ohio, 75 miles to the south, who would rack up his 11th career victory. Denton True “Cy” Young would win exactly 500 more, just a shade north of half of those in Cleveland uniforms.

The Spiders sniffed out championship glory throughout much of the 1890s, spinning together one winning record after another behind Young and fellow Hall of Famers Jesse Burkett and Bobby Wallace; they reached the NL’s 19th-Century version of the World Series (often called the Temple Cup) three times, once winning it all over the heralded Baltimore Orioles in 1895. All this, and the team annually lagged in attendance; maybe the fans were afraid of Zeus, who struck the final nail into the old League Park with a bolt of lightning and tried to strike the first one at the new ballpark in 1892, but the damage this time was limited and a full recovery ensued.

Overall, Robison didn’t blame the lightning or the fans as much as he did Cleveland authorities who insisted on banning Sunday baseball, a hot topic back in the day. Fed up, Robison virtually pulled the plug on the Spiders after 1898, buying the St. Louis Perfectos (Cardinals)—dual ownership was allowed during this time—shipping all his best players to Missouri and leaving the Spiders an embarrassing mess. In 1899, the Spiders won 20, lost 134 and drew a grand total of 6,000 fans; as Robison’s debasement became obvious and virtually nobody came to League Park, it was decided to move most of the remaining home games on the road. After the merciful last out of the year concluded what’s regarded as the worst campaign in major league history, the NL quickly disbanded the Spiders.

The entrance to the original League Park in the early 1900s. The wooden structure was rebuilt with steel and concrete in 1910. (Library of Congress)

New Century, New Blood.

League Park would not be abandoned for long. A young, local millionaire named Charles Somers, one of many baseball fans jilted by the liquidation of the Spiders, got proactive. Called upon by Ban Johnson, who was quietly plotting to start up a second major league circuit, Somers bought the minor league Grand Rapids Rustlers of Johnson’s Western League and moved it to League Park, where a year later they would be upgraded as the Cleveland Blues of the fledgling American League. While the other seven AL franchises hastily sprung up new ballparks, League Park would be the only former National League home initially used in the newborn circuit.

One of the wealthier AL owners, Somers generously gave out or loaned money to the other teams to help stabilize the league; hopefully he was being repaid quickly, for the Blues—who became the Naps once superstar Nap Lajoie escaped to Cleveland in 1902 after a legal tug-of-war between competing Philadelphia teams—constantly finished near the bottom of AL attendance totals. It’s not that Somers wasn’t trying; he kept League Park in good shape, occasionally freshening up the facility and hiring groundskeepers who kept the field in such good shape that it was once favorably compared to a “millionaire’s lawn.” Somers also was putting a pretty good product on the field; besides Lajoie—easily the AL’s best hitter until Ty Cobb came along—the Naps were blessed with Addie Joss, an effectively stifling pitcher who allowed fewer baserunners (0.97) per inning than any other major leaguer, past or present, and got the win in one of the greatest pitching duels ever witnessed when, in late 1908, he outdueled the Chicago White Sox’ Ed Walsh (who allowed a run and struck out 15 Naps) by retiring all 27 batters he faced on just 74 pitches.

The greatness of Joss was cruelly cut short when he contracted tubercular meningitis and died early in 1911, just two days after turning 31. In response, Somers and his players decided to hold an exhibition game pitting the Naps against the best of the rest of the American League to help benefit Joss’ family. The impromptu collection of stars who showed up before a League Park crowd of 15,000 included Cobb, Walter Johnson, Tris Speaker and Frank “Home Run” Baker; it was said to be the first such “All-Star” team to take the field, and although they beat the Naps, 5-3, the most important number of the day was 12,194—the amount of dollars donated to Joss’ widow.

Joss’ legacy at League Park extended beyond the playing field. An enterprising engineer, he used some of his spare time to create the first electronic scoreboard, and League Park put it to good use—although, like most first stabs at technological advances, it initially didn’t always behave as planned.

The so-called “Joss Indicator” was one of the new features of the rebuilt League Park, reborn in 1910 as a steel-and-concrete facility. The $300,000 redo came courtesy of Osborn Engineering, a local firm that had never dabbled in sports structures. But League Park would be the first of many to come, establishing Osborn as the premier architect of baseball’s steel-and-concrete era and beyond.

Little House on the Ballpark.

Osborn’s vision of the modernized League Park was as peculiar as it was beautiful. On the outside, the wooden facades were replaced by a tall red brick exterior adorned with two levels of arched openings, with the lower arches rising nearly two stories high; it was all topped by an industrial green roof that beautifully complimented the vibrant brick red. Folks looking to enter through the original main entrance behind home plate weren’t going to find it; they would now have to walk down the block to the corner of 66th and Lexington, nearest the right-field corner, and enter through a two-story, gable-roofed structure that looked like a wayward house accidentally fused to the main structure.

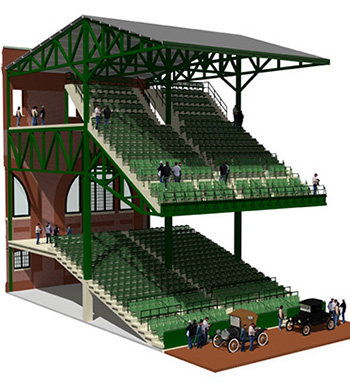

An illustrated segment of League Park’s double-deck structure shows upper-level fans sitting about as close to the playing field as those seated below at ground level. (Thomas Woodman, LegendaryBallparks.com)

Everything old was new again, in more ways than one. Pitching League Park’s second inaugural game was the man who pitched the first, 19 years earlier. Cy Young, recently returned to Cleveland after a fabulous decade with the Boston Red Sox, aimed for his 498th career win at age 43 and lost to Detroit, 5-0.

League Park’s new steel-and-concrete structure was no doubt more fireproof than the wooden original, but Zeus gave it another jolt anyway—this time taking out his fury on the players during a 1919 contest. Ray Caldwell, pitching his first game in front of the Clevelanders following a trade, was knocked down by a bolt of lightning; electrified, he jumped back up and went on to earn a complete-game victory over the Philadelphia A’s, scattering a run on four hits.

Life on League Park’s playing field remained interesting to say the least. Bullpens were now located near the foul poles, cutting into the first-level seating areas; it was thus possible for an outfielder to chase a ball into the pen and fire it back to the infield by throwing it over the spectators. In center, a ball could roll through an opening under the scoreboard and still be considered a live ball; an outfielder could crawl under to get it—but given that he was well over 400 feet away from home to begin with, there was no point to make the futile effort to prevent the inside-the-park home run that, really, wasn’t inside the park. The AL’s first-ever pinch-hit grand slam was said to take place in this fashion when Cleveland’s Marty Kavanagh drove one under the wall in 1916.

Pinball Baseball.

For power hitters, the home run strategy remained the same: Good luck to left field and hello, right.

Which brings us to the right-field wall.

No single part of League Park has probably been discussed more. Originally it was a 20-foot wall bordering along Lexington Avenue, but then the Naps decided to top that with 25 feet of chicken wire to make home runs a tougher task to opposing boomers. One of those guys, Detroit’s Sam Crawford, shrugged—and simply hit it harder, over the fencing.

The unpredictability of the wall—how a ball would react once hitting it—proved popular with fans and highly unpopular with right fielders—or any of the other eight fielders who, on occasion, would find themselves directly involved with the carom. A drive could hit off the lower, concrete half of the wall and rocket quickly back toward the infield. Or it could hit the chicken wire and drop straight down. Or there would be the nightmare scenario for fielders: The ball could hit one of the protruding steel supports, vertically spaced out every 12 feet or so, and ricochet in any direction. For the defense, it was helplessness at its worst. For the fans, it was pinball baseball at its finest.

League Park’s signature element: The 45-foot right-field wall. A ball could sharply ricochet off the lower concrete wall, drop straight down from the screen above, or redirect in almost any direction off one of the vertical steel supports. (Cleveland Press Collection)

Besides preventing cheap home runs, the 45-foot right-field wall was meant to also protect businesses and homes across Lexington Avenue. Apparently, it wasn’t enough. The largest of the buildings, the Andrews Storage Company, was said to annually charge the Indians for the replacement of some 20-30 windows a year during the 1920s. The Indians, in turn, probably would have been inclined to pass the bill on to Babe Ruth—who in 173 career games at League Park hit 54 homers and batted .372, higher than any other ballpark he played in—but they figured that the revenue he and the mighty New York Yankees brought in probably was enough of a financial offset.

Ruth was clearly an exception; after all, he could hit 54 homers out of the Grand Canyon. The truth was, League Park was not a home run haven even with the reduced right field. The ballpark splits, year after year, show fewer home runs hit by the home side than it belted on the road, while opponents on a whole also could never rack up on round trippers. But League Park did yield more than its share of singles and doubles—and a whole lot of runs.

Lexington Avenue was a popular spot for kids before and during the games; they were given free tickets if they scooped up any ball hit out of the park and returned it to the main gate. One lad was lucky enough to get a hold of one of Ruth’s League Park bombs, the 500th of his storied career; for bringing back the memento, he received $20, an autographed ball and a chance to visit Ruth and the other Yankees in the visiting dugout.

Dunn Deal.

By 1915, Charles Somers—whose plentiful wealth helped keep the American League on its feet during its infant days—was financially cleaned out. He was forced to sell, and the franchise, recently renamed the Indians when an aging Nap Lajoie was sent packing, was bought by Chicago railroad magnate Jack Dunn, who vowed to rename League Park after himself—but only if the Indians finally secured their first AL pennant.

Dunn didn’t have to wait terribly long. Behind Cooperstown-bound player-manager Tris Speaker, the Indians ripped through a memorable but emotionally wrenching 1920 campaign that saw the on-field death of popular shortstop Ray Chapman (fatally struck in the head by a Carl Mays pitch) a League Park-season attendance record of 900,000 and their first World Series appearance, defeating the Brooklyn Robins five games to two in a rare best-of-nine format.

For the Fall Classic, Dunn increased capacity to 25,000 by temporarily erecting bleachers halfway down the voluminous right-field wall from center, rising high enough to practically overshoot the fence and hover over the Lexington Avenue sidewalk. Good times followed for the fans who packed League Park for four World Series games, all won by the Indians; Game Five beheld special and historic memories as Elmer Smith hit the first-ever World Series grand slam in the first inning and, in the fifth, second baseman Bill Wambsganss pulled off an unassisted triple play—the only one committed in World Series history and only the second in the modern (post-1900) era. The first had occurred 11 years earlier—also at League Park.

Dunn Field was renamed as promised after the Indians’ successful 1920 pursuit of the pennant, but the man in charge only got to enjoy the ego trip for a few years. In 1922, Dunn passed away; his widow took over as an absentee owner (allowing established baseball men to run the club) before selling in 1927. The new owners, led by local businessman Alva Bradley, showed no sentimentality toward Dunn and officially went back to calling the place League Park.

Something Big on the Horizon.

Shortly thereafter, League Park faced its mortality for the first time. In 1928, Cleveland voters gave their okay to build the big new kid on the block: Cleveland Municipal Stadium. The multi-purpose facility would be massive—its 78,000 seats would be nearly four times the capacity of League Park—and was to ideally serve as the host for all major Cleveland sports activities. The question became not one of whether the Indians would leave League Park for the monstrous new stadium, but when.

“When” would be nailed down in the middle of the 1932 season, a year after the final touches were applied to Cleveland Stadium. The Indians’ pitchers were certainly anxious to get out of League Park; they’d had enough of the offensive high times that had dominated since the start of the live ball era a dozen years earlier. There was plenty of fodder to fuel their frustration at League Park, which had conceded a .300 average since 1921, provided the setting for a 1923 game in which the Indians piled up a then AL-record 27 runs and, just three weeks before what was to be the Tribe’s permanent move to Cleveland Stadium, bore witness to one of the wackiest games ever played: An 18-17, 18-inning loss to the Philadelphia A’s, a game featuring an all-time record nine hits from Cleveland infielder Johnny Burnett and three home runs from Jimmie Foxx, none of which cleared the left-field bleachers.

The Indians’ first two games at Cleveland Stadium also came against the A’s, but it became immediately evident that nonstop offense would not reign. Philadelphia won the first game, 1-0. It won the second, 1-0. Seduced by the potential for monster crowds, the Indians did draw 80,000 to the initial game—but then had 12,000 for the second game, and far fewer for the remaining games played that year at the cavernous venue. A year later in 1933, the Indians stuck it out at the Stadium and found the experience sobering; there were a few big crowds, but a lot of small ones that all but disappeared within a double-decked sea of empty seats. The 387,000 fans who showed up for the season was a lower total than the average gate at League Park. And while the pitchers were happy—Cleveland Stadium yielded far less offense—no one else within the Indians organization was. Certainly not the hitters, and, more importantly, neither was the front office—which began to wonder what the point was of paying all that rent outside of team-owned League Park if fewer fans were going to show.

League Park, sitting comfortably within the Hough neighborhood east of downtown Cleveland in the 1930s. The area would deteriorate into a borderline slum by the late 20th Century, but is currently experiencing a gentrification.

And so the Indians came home to League Park in 1934, essentially staying there full-time for the next three seasons as they freshened things up with new paint, new seats and five feet of chicken wire sliced away from the top of the right-field fence to give left-handed sluggers Earl Averill and Hal Trosky a little extra home run muscle on the Cleveland stat sheet.

The team did schedule one game at Cleveland Stadium in 1936, drawing 65,000 against the Yankees on a Sunday afternoon in August. This perhaps planted the seed within Indians management to have it both ways—using the big bowl when large crowds were anticipated for games on weekends, holidays and whenever the star-studded Yankees came through, then scheduling the rest of the games at League Park. This scheme would more or less be the pattern for the next 10 years, with gradually more games being held at Cleveland Stadium; the trend would accelerate in 1939 when lights were installed at the bigger venue, leaving League Park as, basically, a weekday-only alternative. (League Park did get in one night game when portable lights were used for a 1931 Negro League game.)

One Team, Two Residences.

The schizophrenic nature of the Indians’ home life—playing at an elephantine stadium with spacious field dimensions one night, then at a cozy abode the next—at least provided a happy medium for Cleveland players; the hitters would be content at League Park, the pitchers equally so at Cleveland Stadium. During the 11 years in which the Indians’ home schedule was split somewhat evenly between the two parks, there were 80 occurrences of double-digit scoring at League Park—and only 20 at Cleveland Stadium.

After a while, opposing teams began to grumble that the Indians were being strategic on more than just a financial level when choosing which park to schedule their games. The basic complaint: Visiting teams with lots of slugging muscle would find themselves more often than not at Cleveland Stadium—where home runs where far harder to come by. True or false, fair or not, the Indians rarely faltered in either home, and especially at League Park; over the team’s last 17 seasons there, they never once suffered a losing record.

Joe DiMaggio hits away at League Park in a game that would mark his 56th straight with a hit in 1941. The streak came to an end one day later—at the Indians’ “other” home park, Cleveland Stadium. (The Rucker Archive)

Even as it became a part-time participant in the Indians’ life, League Park continued to provide memorable moments late in its prime. It hosted the debut of supersonic ace Bob Feller, who at the tender age of 17 took the mound for a 1936 exhibition against the heralded St. Louis Cardinals—and proceeded to blow away eight of them via strikeout in just three innings of work. Five years later, Joe DiMaggio extended his fabled hitting streak to 56 games at League Park with a double and two singles; the next night, at Cleveland Stadium, the run ended.

Midway through the 1946 campaign, the Indians were sold to maverick promoter Bill Veeck, who had created success both on the field and (especially) at the gate wherever he had previously gone. Confident that his bag of promotional tricks would be too big for League Park, one of Veeck’s first moves as head Indian chief was to cut a deal with the city to use Cleveland Stadium on a full-time basis, starting in 1947. This time, there would be no going back to League Park; 14 years after the first official finale, the Indians played a second one—this time, definitely—on September 21, 1946 in a 5-3, 11-inning loss to the Tigers. A small gathering of 2,772 soaked up the moment for all it was worth.

Two years later, Veeck indeed proved that his marketing genius was better suited for a bigger house. In winning their second world title, the Indians drew a then-major league-record 2.6 million fans to Cleveland Stadium—an average of nearly 34,000 a game, or 12,000 more than League Park’s capacity.

And still, there were rumors that League Park’s days as a major league facility was not over. When Veeck began new negotiations for the continued use of Cleveland Stadium in 1950, he used the old ballpark as a bargaining chip. Osborn Engineering, the firm responsible for the steel-and-concrete rebuild 40 years earlier, drew up a $1.25 million budget to increase League Park capacity to 35,000—extending the existing double-deck structure around the left-field foul pole and all the way to center, as was done with Brooklyn’s Ebbets Field—and outfit it with lights. The proposal died at the blueprint stage; Veeck got what he wanted from Cleveland Stadium, and the Indians would remain there into the 1990s.

Down, But Not Out.

A stage of semi-retirement followed for senior citizen League Park following the abandonment of the Indians. Negro League teams performed there through 1950. A portion of the film The Kid From Cleveland, about a juvenile delinquent attempting to be turned straight by the Indians, was filmed there and featured current-day Indians stars Bob Feller, Lou Boudreau and Satchel Paige. Apparently the film didn’t leave a lasting impression; it doesn’t even appear in Leonard Maltin’s Movie Guide.

The upper deck was razed in 1951, as it was figured it wouldn’t be needed to accommodate the few fans showing up for the ballpark’s one remaining tenant: Football’s Cleveland Browns, who used League Park as a practice facility. Following the Browns’ departure in the mid-1960s, a dark age descended upon League Park and the Hough neighborhood surrounding it. Once a thriving middle-class neighborhood, Hough became rough—and, one day in 1966, very angry when a bar in the area posted a sign saying, “No Water for Niggers.” What followed was nearly a week of rioting from within the predominant African-American community, resulting in four deaths, 30 critical injuries and scores of local businesses burned to the ground.

League Park was spared the chaos, but by then there wasn’t much left of the facility to spare. Little by little, the ballpark was deconstructed, and the property took on more of a recreational feel, with a community swimming pool and basketball court added amid the field grass and concrete bases. The playing field remained, and on occasion local pickup teams with a fondness for the past would take to the diamond and revive old times—bringing a lawn mower with them to cut the grass while (carefully) cleaning up any liquor bottles and drug paraphernalia left behind.

League Park today. The ticket office house at the corner of 66th and Lexington (left) remains from the original ballpark; the screen fence is a virtual recreation of the one that stood high over right field back in the venue’s prime. (Google Earth)

By 2003, all that was left of League Park was the ticket office house on the corner of 66th and Lexington along with the wall remnant from the ballpark’s west façade. Nobody had used the house, except to throw rocks through its windows.

Just when it appeared that League Park would become a total memory and nothing more, a phoenix rose to save the day. Hough resident and Cleveland councilwoman Fannie Lewis dreamt up the idea of reviving League Park, not as a big-league park but as an upscale recreational park with echoes both physical and symbolic of the old ballpark. Through the morass of the usual city bureaucracy and politics, Lewis muscled up a $6.3 million budget to achieve her vision.

In 2014, six years after Lewis’ passing, League Park came back to life. The field dimensions remained the same. The tall, unpredictable right-field fence was replanted. The ticket office house now hosts the Baseball Heritage Museum, celebrating a century-plus of Cleveland baseball. And there’s just enough aluminum bleachers hugging the infield to hold a typical gathering of Little League supporters.

League Park, 21st-Century style, has helped usher in a era of renewed hope for the Hough neighborhood. New homes, some of them quite upscale, mix in with older houses and enough open space to make one wonder if the countryside is attempting to win the land back. New businesses are springing up. And you know gentrification is in full swing when a winery opens up nearby.

League Park will probably never host the Indians again, but at least it lives on as an ode to the greatness of yesteryear. Local residents can walk its grounds and feel good about what currently is. And once what was.

The Ballparks: Cleveland Municipal Stadium Orderly as it was ordinary, obese as it was austere, Cleveland Municipal Stadium was that rare baseball structure of the early 20th Century, hailed not as a monument to a team owner but to civic pride in a city feeling its oats about the future. Golden moments would ensue, but rust would quickly overtake the stadium and its baseball tenant, rousing cynical locals to declare it “The Mistake by the Lake.”

The Ballparks: Cleveland Municipal Stadium Orderly as it was ordinary, obese as it was austere, Cleveland Municipal Stadium was that rare baseball structure of the early 20th Century, hailed not as a monument to a team owner but to civic pride in a city feeling its oats about the future. Golden moments would ensue, but rust would quickly overtake the stadium and its baseball tenant, rousing cynical locals to declare it “The Mistake by the Lake.”

The Ballparks: Progressive Field The Cleveland Indians once played at Municipal Stadium, an aging monstrosity often referred to as the “Mistake by the Lake.” Those few who showed up to watch the Tribe saw them as clueless yet lovable losers. But when Jacobs (later Progressive) Field opened in 1994, not only did the Indians’ fortunes turn in a positive direction, so did the psyche of Clevelanders. Not a bad turnaround for a city once laughingly looked upon by outsiders as a decayed, national joke.

The Ballparks: Progressive Field The Cleveland Indians once played at Municipal Stadium, an aging monstrosity often referred to as the “Mistake by the Lake.” Those few who showed up to watch the Tribe saw them as clueless yet lovable losers. But when Jacobs (later Progressive) Field opened in 1994, not only did the Indians’ fortunes turn in a positive direction, so did the psyche of Clevelanders. Not a bad turnaround for a city once laughingly looked upon by outsiders as a decayed, national joke.

Cleveland Indians Team History A decade-by-decade history of the Indians, the ballparks they’ve played in, and the four people who are on the franchise’s Mount Rushmore.