THE BALLPARKS

Nationals Park

WASHINGTON, D.C.

(Library of Congress—Carol M. Highsmith Archive)

Build it on your own dime, and they will come—not just Major League Baseball, but an adjacent community full of new residents flocking to gleaming high-rise developments, ruining the view of D.C. monuments for fans in the stands but re-energizing a once-derelict chunk of town. What Nationals Park lacks in aesthetical wow, it more than makes up in terms of urban renewal and ecological rebirth.

You got to give the people who built Nationals Park points for trying. They include the politicians who arm-wrestled with MLB honchos, skeptical citizens and even themselves, agonizing and quarreling over a ballpark budget they were rudely handed the check for. They include architects who wanted to “change the paradigm” of ballparks with a structure that envisioned a modern, transparent ode to democracy, before budget cuts turned it into something more akin to a corporate office building. And they include the construction workers who, forced with a tight turnaround, built blindly at times as the ink on the blueprints had yet to dry.

You got to give the people who built Nationals Park points for trying. They include the politicians who arm-wrestled with MLB honchos, skeptical citizens and even themselves, agonizing and quarreling over a ballpark budget they were rudely handed the check for. They include architects who wanted to “change the paradigm” of ballparks with a structure that envisioned a modern, transparent ode to democracy, before budget cuts turned it into something more akin to a corporate office building. And they include the construction workers who, forced with a tight turnaround, built blindly at times as the ink on the blueprints had yet to dry.

Nationals Park will qualify neither as ballpark architecture’s finest hour, nor its worst; the standard reaction to its design is a hand-rocking meh motion. But the home of the Washington Nationals is hardly flawed; in this ballpark, function clearly triumphs over form with splendid sightlines from both seat and concourse, while bending over backward to help save the environment. In those cases, transparency does rule.

What is fascinating about Nationals Park are the numerous struggles in making it a reality, the ups and downs the venue and its prime occupant have endured since its opening, and the surrounding community that has sprouted and prospered because of it. Few, if any, cities have experienced a more successful transformation of a ballpark district from slum to signature neighborhood.

“None to Disrupt.”

A major market without a baseball team since 1971, Washington began salivating in 2002 when MLB commissioner Bud Selig dangled the Montreal Expos, who MLB owned after a scheme to dissolve the team hit a legal brick wall, to the city that most wanted them. There was one condition: No city could obtain the Expos without building a new ballpark, fully paid for with public dollars.

Selig had already publicly teased Washington as a “prime candidate” for a relocated team, but the locals had to be pardoned for squinting through the hope; over the previously three decades, their city had been denied again and again for either an expansion or relocated team. D.C. would receive additional stress from the immediate south in Northern Virginia, where there were deep-pockets stakeholders seeking to build their own ballyard, and from the immediate north in Baltimore—where Orioles owner Peter Angelos, chafing at the threat of MLB competition a mere 40 miles away, derided Washington as having “no real baseball fans.”

Still, the Expos were Washington’s to lose, and Mayor Anthony Williams knew it. Of course, it wouldn’t be easy; besides having to convince Washingtonians to plunk hundreds of millions into a new ballpark some 10 years after the city nearly went bankrupt, Williams had to go find a spot where the danged thing could be built. Among the sites considered were several locations just east of downtown, RFK Stadium (with the existing structure renovated) and, more ambitiously on the southwest end of the district, a space where a ballpark would sit over Interstate 395.

Lower down on the list, both geographically and popularly, was the Capitol Riverfront in the city’s southeast end along the badly polluted Anacostia River. It was the ugly duckling of the candidates; seemingly cut off from the rest of the city by the interstates to the north, the Capitol Riverfront was bookended by the Washington Navy Yard and the Army’s Fort Leslie J. McNair. In between was an expanse of land described by the Washington Post’s Marc Fisher as a “desolate, industrial, frightening landscape.” It included pockets of low-income housing, asphalt plants, taxi depots, auto repair shops and adult stores and clubs, one of which was called In & Out. “It’s a non-starter,” wrote Fisher of the area. Many others agreed.

Sharon Ambrose had a different take. The D.C. councilwoman whose district included the Capitol Riverfront saw an opportunity for a ballpark to ignite development and restore dignity to the semi-blighted area. Brushback from within would not be an issue. “In terms of disrupting a residential neighborhood,” Ambrose told the Post, “there really is none to disrupt.”

A Game of Chicken.

Long before the Capitol Riverfront was chosen as the site for Nationals Park—and before MLB had made the Expos available to the highest bidder—Mayor Williams pledged $200 million in public money for a new ballpark. But as fantasy became potential reality with the Expos hitting the free-agent market, and as budgetary negotiations thus became more serious, the estimated ballpark cost rose. And rose. And rose again. The initial $200 million became $338 million, then $440 million, and then over $500 million and $600 million. As the proverbial counter grew like that of the national debt—and with polls showing up to 70% of residents unhappy with the idea of public funding—the mayor and his 13-member council considered ways to offset the growing projected costs beyond the business taxes and ballpark rent payments initially considered. One idea suggested a scheme in which $100 million would be collected from curbside parking within the Capitol Riverfront area, which engendered skepticism. Another idea was to levy a 5% tax on the salaries of Nationals nee Expos players, before the players’ union hammered back with the threat of legal action.

The haggling within City Hall was compounded by the arm-wrestling taking place between D.C. and MLB. The league said it wouldn’t officially relocate the Expos to Washington until the city approved a ballpark finance plan. The city, in turn, said it wouldn’t approve the plan until the league committed to the relocation. This game of chicken would go on for nearly two full years.

MLB eventually blinked. At the end of September 2004, the league formally announced the Expos’ move to Washington, making a deal with Williams on ballpark financing which, for the moment, was listed at $440 million. Though both sides still had to get binding approval—Mayor Williams from his city council, MLB from its owners—the city held the upper hand as they had an existing major league-level ballpark (RFK Stadium) to use in the interim, whereas all other city candidates had none. The last thing MLB wanted to do was return the Expos to their lame-duck realm of Montreal, or jet them a million miles away to Puerto Rico—where the team played a quarter of its home schedule over the previous two seasons.

The euphoria of Baseball’s impending return to the Nation’s Capital began to wane within the D.C. Council. As a December vote to approve ballpark financing loomed, council chairwoman Linda Cropp sensed the momentum among her colleagues was slipping toward a minority of “yes” votes. To gain back majority approval, she lobbied for a new provision: 50% of the ballpark’s financing had to come from private sources. This major tweak was added and the legislation approved, seven votes to six, by the council.

MLB was furious. The league was understandably troubled over the council’s 50% demand for private funding when such financiers were nowhere to be found. Responding with optical leverage, MLB suspended all merchandise sales of the Nationals, began refunding season ticket payments, and postponed an unveiling of the team’s 2005 jerseys. The Nationals were little more than three months away from playing their first game at RFK Stadium—maybe.

From this point on, Cropp became more of the prime point person with MLB over Mayor Williams, whose backroom negotiating skills were said to be his weak point. Over the next week, Cropp took private financing off the table—but in return, the city wanted MLB to share the cost of insurance against any construction overruns, and reduce the financial penalty for not finishing the ballpark by its scheduled March 2008 opening date. A new vote was taken by the council and approved, 7-6—with the deciding vote cast by Cropp, who chalked up her pushback stances and compromise chats with MLB as “good government.”

Little did anyone know, this was just the beginning.

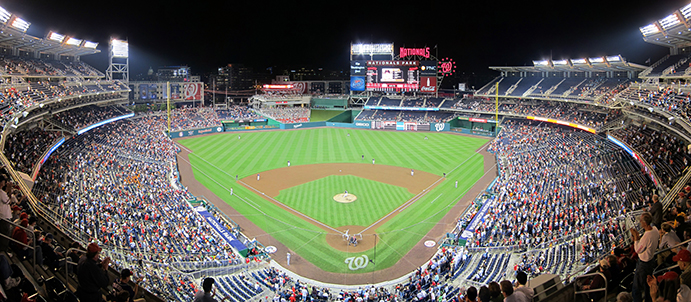

The interior of Nationals Park at night. The outfield wall angles (particularly in right field) and the upper deck seats around the right-field pole—separated from the rest of the ballpark bowl—are modest nods to Washington’s old Griffith Stadium.” (Wikimedia—Something Original)

A Sharp-Edged Look.

With the hard part done—for now—the fun part commenced with the designing of Nationals Park. HOK Sport was chosen out of three competing architects, because it was the most inexpensive option and, certainly, the most experienced—an important factor given the ballpark’s tight timeline from concept through construction. Assisting the Kansas City-based HOK with local insights was black-owned architect firm Devrouax and Purnell, from which one of the principals (Marshall Purnell) had once been a budding ballplayer scouted by the Boston Red Sox before turning his focus to architecture.

After its usual walk-through audit of D.C.’s architecture, HOK came away impressed with what senior project designer Jim Chibnall described as the “beautiful, simple shapes” of the city’s museums and monuments. Any idea of retreating to the now-tiring trend of throwback ballpark design was not even discussed. Washington Post columnist Thomas Boswell agreed when he wrote, “The District’s world-famous monuments aren’t 19th-century industrial.”

Of particular interest to Chibnall and HOK principal Joe Spear was the East Wing of the National Gallery of Art, a limestone-and-glass structure fusing segmented shapes of parallelograms and triangles so tight that one could want to easily slice a piece of paper by forcing it against its sharp edge. Spear, in particular, was taken by the timeless look of the gallery, built in the 1970s. The East Wing’s influence on Nationals Park would be most apparent at the ballpark’s southwest corner with a sharp, triangular split from the rest of the ballpark’s U-shaped structure; the three-story appendage is home to the Nationals’ team offices.

Nationals Park’s architecture would be persuaded by other local points of interest. The first base gate is preceded by a wide collection of steps, much like those fronting the U.S. Capitol or Lincoln Memorial. The backstop walls between both dugouts are composed of mica-schist stone, similar to the canal walls in nearby Georgetown. And the Nationals’ clubhouse has an oval shape that seems to owe to the Oval Office at the White House—but that had more to do with enhancing team chemistry. Marshall Purnell, in San Francisco as part of a fact-finding trip of other ballparks, noticed how HOK-designed Oracle Park included a rectangular locker room where Giants superstar Barry Bonds had commandeered a corner like it was his own private lounge. “You don’t want a niche where two of three players can get off by themselves and create their own little world,” remarked Spear. “You want them to feel they’re part of the team.”

There would also be odes to Washington ballparks of the past. The outfield wall in right field, with straight-line segments and a detour-like notch, is mildly (and intentionally) reminiscent of Griffith Stadium, as is the separation of the two upper decks near the right-field corner from the rest of the main structure to bring spectators closer to the action. Memories of RFK Stadium abound in the deepest reaches of the upper decks, where the ballpark’s blue seats contain a few repainted in red to denote where some of the yard’s longest home runs have been hit. That’s a nod to Frank Howard, whose titanic shots in the 1960s encouraged RFK workers to paint his faraway landing spots white amide that venue’s mustard-colored seats. (Ironically, the spot where Nationals Park’s longest home run to date was hit—a 473-foot drive by Bryce Harper in a 2018 game—is not painted, because it landed on the batter’s eye area in center field.)

Here We Go Again.

HOK Sport’s ambitious vision of a ballpark made of steel, glass and limestone proved too expensive for council chairwoman Linda Cropp, who broke out the red pen and told the architects to minimize the use of glass while using precast concrete as a faux substitute for the limestone. “We’ll have to redo some things and not be able to do a Cadillac stadium,” said Cropp, “but we could do a Buick or a Ford.”

While those cost-cutting measures slowed the bleeding, it didn’t stop it. Nationals Park’s budget continued to rise; whereas most cost overruns at new ballparks are typically covered by the teams that inhabit them, D.C. would be stuck with the bill on Nationals Park per MLB’s demands. A bank loan was considered to cover half of the ballpark budget, but the anticipated debt service would have cost the city even more money in the long run. Meanwhile, chatter intensified again on the RFK site, with even some on MLB’s side acknowledging that option as a possible last resort.

Upcoming lease negotiations on Nationals Park, initially considered to be a drama-free formality, instead blew up into Round Two of expanded financing talks. This time, the city wanted MLB to pitch in and cover a portion of the overruns and a $24 million letter of credit in case ballpark activity would be neutralized by a work stoppage, terrorist attack or, more presciently, a pandemic. MLB agreed to all of the above along with a $5.5 annual rent paid by the Nationals over 30 years, and an additional dollar for every ticket sold above 2.5 million per year.

Once more, approval was left up to the City Council; once more, they hemmed and hawed. Cropp and Co. wanted to cap budget spending to a level lower than MLB had in mind, tried desperately to seek more cuts in HOK’s spending, and looked into funding from local developers in exchange for exclusive rights to develop portions of the area outside of the ballpark.

Thinking once more that they had a deal, MLB went back to the negotiating table with Mayor Williams more irate than ever. Weeks of intensive talks ensued, and a new lease/finance plan that everyone was supposed to be happy with was put to a council vote on February 7, 2006. Except the council voted it down, 8-5.

Enough, fumed Williams. In what must have been a “Come to Jesus” moment, Williams told the council to stop fooling around and consider the consequences of a no vote. Those included an arbitration already filed by MLB, a potential lawsuit by the league for violating the earlier agreed-upon release—or just folding up tent and moving the Nationals to another city.

Later that day, the council voted again. It approved the lease by a 9-4 count.

MLB commissioner Bud Selig, catching his breath from four years of dueling with D.C., didn’t hold back his feelings. “You think you’ve seen it all. And then you realize you haven’t,” he said. “I’ve been involved in 18 stadium negotiations…but this thing that happened in Washington tops them….When it comes to demagoguery, a lot of what happened down there would have made Huey Long blush.”

Others felt that Selig essentially got away with a free new ballpark. Ed Lazare, executive director of the DC Fiscal Policy Institute, told the New York Times: “Even among stadium deals, it’s pretty unusual for the city to cover 100% of the cost. (MLB) got everything.”

Looming behind the left-field bleachers is one of two four-story parking garages, considered Nationals Park’s biggest eyesore. Ads and banners cover up the façade for extra revenue—while hiding the ballpark’s reputation as looking like an office building, especially from the outside. (Flicker—Adam Fagen)

Learning With the Lerners.

Exhausted from the countless negotiations with MLB, D.C. now had to deal with Ted Lerner, who formally bought the Nationals from MLB on the same day the first shovels officially went into the ground at Nationals Park.

The 80-year-old shopping mall magnate, old enough to have been an usher at the 1937 All-Star Game at Griffith Stadium, would prove to be no picnic with the city’s ballpark overseers. Along with his son, Mark—who would take over day-to-day operations of the Nationals’ in 2018—Lerner became an intense stickler for details and the fine print. “These are the guys who invented hardball,” remarked Allen Lew, chief executive of the DC Sports and Entertainment Commission, to the Washington Post.

The first clash between the Lerners and the city involved two parking garages placed at the north end of Nationals Park. The city wanted the garages fully underground so that they could develop revenue-generating retail spaces above it, but Lerner advocated for them to be above ground as they would be safer, easier to access and both cheaper and quicker to complete, an essential point considering the ballpark’s tight construction timeline. The twin four-story structures, each bookending Nationals Park’s center field gate where most fans arrive, have unarguably become the ballpark’s biggest eyesores. Oversized ads and player banners often cover the sides of the garages facing inside the ballpark.

There were later tug-of-wars, one involving the close proximity of licensed vendors hawking food and souvenirs—Lerner pressured the city to push them further away from the gates, never mind the number of bars and restaurants within easy walking distance of the ballpark. Even after the ballpark’s opening in 2008, the Lerner regime refused to pay rent and asked for $100,000 a day in damages because, it claimed, Nationals Park hadn’t been “fully” completed. D.C. officials admitted that there was still some last-minute work to be done on the Nationals’ triangular team offices, but firmly held that the rest of the facility was done and cited the team’s over-reaching claims as “petty.”

In their quest to make Nationals Park more of the Cadillac and less of the Ford or Buick as Linda Cropp earlier conceded, the Nationals under Lerner anted up $50 million of their own money to install an improved main scoreboard, a bigger out-of-town board, a doubling in size of a bar/restaurant behind center field with a circular LED display atop it, and more convenient amenities for the nearly 80 suites. Of course, the Nationals gave it the ol’ college try by asking the city to pay for these upgrades, but an arbitrator intervened and said, “Nope.”

One last major structural adjustment was made by the Nationals behind home plate, insisting that all of the ballpark’s main suites be located between first and third base. (There are 10 additional “party” suites situated down the left-field line.) This meant a double-decking of the suites, pushing not only the upper two decks higher but also the press/broadcast booth to the very top of the ballpark. It’s a helicopter-like view that broadcast crews like to point out whenever they visit Nationals Park, but it does get them closer to heaven and the man the press box is named after: Shirley Povich, the legendary local sportswriter who from the 1920s through his death in 1998 covered the preciously good, often bad and recent non-existence of Washington baseball.

The first game at Nationals Park, with the Nationals winning on Ryan Zimmerman’s walkoff home run in the ninth inning on March 30, 2008. Note the red press box high atop the upper deck behind home plate; no other MLB ballpark provides broadcasters with as high a helicopter-eye view of the action. (Flickr—Daniel)

Just Win One for Stephen.

Finally, in late March 2008, there was baseball at Nationals Park. First, a game pitting two local college teams (George Washington and Saint Joseph) before a crowd topped out at 3,000; second, an exhibition between the Nationals and Baltimore Orioles in front of 30,000 fans consisting of ticket holders, dignitaries and those who helped build the ballpark; and finally, the official home opener on March 30 against the Atlanta Braves before a packed house.

On a chilly Sunday evening game nationally telecast on ESPN, former Texas Rangers owner and current U.S. President George W. Bush threw out the ceremonial first pitch, extending a Washington baseball tradition that began with William Howard Taft in 1910. Former D.C. councilmember Adrian Fenty, Anthony Williams’ successor as mayor and, before that, a staunch opponent of Nationals Park, made peace with the moment and bellowed out “Play Ball” into the public address mic. The Nationals scored two quick runs in the first inning, a small lead they held until two outs in the ninth—when Washington catcher Paul Lo Duca let a pitch slip by, allowing the Braves to tie the game.

The passed ball only delayed the celebration by 10 minutes. With two outs in the Nationals’ ninth and no one on base, Ryan Zimmerman—nicknamed Mr. National for his presence on the Washington roster from his first full season in 2006 all the through 2021—launched a drive that just cleared the left-center field wall and into the first row of bleachers, giving the Nationals a walkoff 3-2 win. Zimmerman’s blast would be memorialized with the padded seat struck by his winning ball repainted blue amid two sections of red seats in front of what’s now called the Change-up Food Hall.

Nationals Park’s grand opening was as good as it got for both the ballpark and the Nationals over the next two years.

After their exciting Opening Night win, the Nats lost their next five home games—restoring reality to a team that was the majors’ worst. The 2.32 million fans who showed up for Nationals Park’s inaugural season were the fewest for a new yard since the similarly awful Minnesota Twins opened the Metrodome in 1982. More alarmingly, the total gate was nearly 400,000 below the 2.7 million who showed up at aging RFK Stadium for the Nationals’ first D.C.-based season three years earlier.

Reviews of the new ballpark were not much kinder than those given to the last-place Nationals. Washington Post art and architecture critic Philip Kennicott was particularly nasty, labeling Nationals Park’s look as the “architecture of the distraction” for the team’s need to prioritize monetizing over aesthetics, the twin parking garages as “disastrously situated,” and assailing the finishings within the suites as comparable to those found in an RV. Kennicott added that although RFK Stadium was, visually, a “better building” but a “lousy experience,” Nationals Park was, by stark comparison, “a great experience, but, alas, a lousy building.”

Things only got worse in the team’s second season at Nationals Park. Tickets prices were largely reduced to draw in more fans, but only 1.8 million showed up. The priciest seats near and behind home plate were largely unsold or unused during the game, perhaps an indication that anyone who showed up was more entertained by the ballpark’s exclusive clubs than the Nationals’ awful play on the field. At one of those joints, the President’s Club behind home plate, a ballpark employee was stabbed by another during an argument. And way up in the press box, Philadelphia Phillies’ Hall-of-Fame broadcaster Harry Kalas, perhaps hoping to truly speak with the ghost of Shirley Povich, collapsed and died shortly before the ballpark’s 2009 home opener. The Nationals lost 100 games, again, and someone providing the team’s uniforms couldn’t spell, as the Nats took the field one game wearing jerseys that said, “Natinals.” But to the losers went the spoils: Picking first in the amateur draft from two years of extreme woe, the Nationals were able to select electric ace Stephen Strasburg and wunderkind slugger Bryce Harper for the future.

The Nationals’ dreadful performance during their first two years at Nationals Park was best epitomized by Stephen Krupin, a fan who attended 19 games at the ballpark in 2009; the Nationals lost all 19. His cousin, a PH.D. economist, figured that the odds of anyone enduring through that torture was one in 131,204.

This unique statue of former Washington Senators pitching great Walter Johnson shows multiple arms and baseballs sprouting outward in an attempt to display motion—but it looks more like something out of John Carpenter’s remake of The Thing. The Johnson statue, seen here in its original spot in the center-field plaza, has since been moved along with two other similar statues to outside of the ballpark, near the home plate gate. (Flickr—Adam Fagen)

Food, Art, and Dead Presidents.

Poor Stephen Krupin at least had the opportunity to enjoy Nationals Park’s “architecture of distraction” as Philip Kennicott so dismissively described the ballpark. In the expansive center-field plaza where most fans filter through toward their seats, 14 cherry blossom trees beautify the otherwise concrete plateau. Nearby is the two-story Change-Up Food Hall, fronted by cascading levels of 80 food tables situated behind the left-center field seats. If one is looking for good eats to take to their seats, local favorites are represented by Ben’s Chili Bowl and Chesapeake Crab Co.

If you’re among the more privileged, you may get access to some of Nationals Park’s more exclusive clubs. They include the FIS Champions Club, which is the closest thing to an actual museum within the ballpark with display of memorabilia including the Nationals’ 2019 World Series trophy; the PNC Diamond Club, located behind the home plate seats with all-inclusive food and drinks, and patio tables for fans to dine and enjoy the game all at once; and the Terra Club (formerly the President’s Club), an upscaled dining experience with views of the formal press conference area and the Nationals’ batting cages.

For visual enjoyment beyond the game, there’s plenty to set your eyes upon. Within the main concourse is a display of archival photographs and history of Washington baseball provided by the Library of Congress. There’s the Washington D.C. Sports of Fame, which admittedly consists of nothing more than a giant banner covering the exterior of one of the ballpark’s garages, complete with a list of all of its inductees. In terms of art, there’s The Ballgame, a group of large circular mobiles hanging over the fans on the first-base side of the main concourse, with colorful 2D art of ballplayers illustrated by Walter Kravitz; and, tucked away behind in the center-field plaza is an untitled, energetic and modern hodgepodge of a mural portraying D.C. Baseball by local artists No Kings Collective, completed in 2019. Strangely, the mural is interrupted near its right end by a door-sized plaque dedicated to legendary Washington Senators pitcher Walter Johnson.

If all of the above isn’t enough to quench your thirst for local baseball history, then you would need to catch Nationals Park’s “history walk” that may be the ballpark’s best-kept secret, given its obscure location outside of the home plate gate where few fans rarely enter. As one strolls along the walk toward the gate, milestone moments in D.C. baseball history (from 1859 to the present) are laid out in chronological order, accommodated by silvery kiosks explaining what happened on said dates.

Also joining along for the walk are Nationals Park’s only three statues, of Walter Johnson, Frank Howard and Negro League legend Josh Gibson, whose Homestead Grays played half of their games in Washington. The statues, originally placed in the center-field plaza in 2009 and moved six years later to their present location, attempt to show bronze in motion—but the effect of Ormi Armany’s works could be better described as bronze icicles, or a transformation not unlike that seen in John Carpenter’s The Thing, or as the Washington Post’s Blake Gopnik put it, “how you’d commemorate the Elephant Man.”

Perhaps Nationals Park’s biggest “distraction” has become the Presidents Race, a variation of the famed sausage races held in Milwaukee. Actually begun at RFK Stadium two years before Nationals Park’s opening, the Presidents Race involves tall mascots portraying George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln and Teddy Roosevelt—although there have also been cameos by William Howard Taft, Calvin Coolidge and Herbert Hoover. Whoever portrays Teddy has typically been slow as molasses; he didn’t win a race until the seventh year of the event. The Presidents hang out in the center-field plaza before games, posing for pictures with arriving fans.

Play Baritone! One of Nationals Park’s bigger non-baseball traditions has been its Opera in the Outfield series, featuring nearby performances shown live on the big video board. Crowds for the events have been known to reach 20,000. (Flickr—Adam Fagen)

Besides Baseball.

Nationals Park isn’t just for baseball. In fact, its largest-ever crowd didn’t involve the Nationals; less than three weeks after the ballpark’s official opening, Pope Benedict XVI held mass before a crowd of 46,000—one of two events he attended in America, the other being another mass days later at old Yankee Stadium in New York. The first major concert took place a year later when Elton John and Billy Joel took the stage together, followed in later years by the Dave Matthews Band, Bruce Springsteen, Paul McCartney, Taylor Swift, Carrie Underwood, The Eagles, Green Day, Lady Gaga, Shakira, Sting, and The Lumineers.

Other events at Nationals Park have included local high school championship games, the annual Congressional Baseball Game pitting Democrats and Republicans (it’s assumed there are no cries of rigged umpiring), the Savannah Bananas, televangelist Joel Osteen, an annual beer festival, and university commencements. The Opera in the Outfield, a longstanding Nationals Park staple, consists of gatherings up to 20,000 watching simulcasts of D.C. opera on the ballpark’s large scoreboard. Finally, Nationals Park in 2015 was host for the popular NHL Winter Classic, featuring the Washington Capitals and Chicago Blackhawks. Nationals general manager Mike Rizzo was one of 42,832 attendees and was booed—not for any criticized decision making, but because he wore a Blackhawks jersey.

A Victim of Its Own Magnetism.

As anticipated, Nationals Park’s presence sparked a landgrab of development within the Capitol Riverfront, particularly north of the ballpark along Half Street where a tundra of blight was ready to be transformed into a swanky new neighborhood. Property values went through the roof as developers vied for the most optimal sites; the U.S. Department of Transportation staked its claim two blocks to the northeast of the ballpark with its new headquarters, while the FBI briefly thought of following suit. Even Amazon, in its much-publicized (and highly competitive) search for its second headquarter complex in 2018, had the Capitol Riverfront on its short, final list of candidates before opting for nearby Northern Virginia—which must have given the people there a sense of getting even with Washington for losing out on the Expos.

The gentrification of the Capitol Riverfront proceeded at a much slower pace than anticipated, its growth stunted by the Great Recession of 2008-09. Even after the economy recovered, people began to wonder if Half Street was named as such because half of the land around it was still flat, empty lots.

Nationals Park would become a victim of its own magnetism in one respect. The Nationals knew the proliferation of upscale high-rise residences, office space, and street-level retail and restaurants was inevitable, making worthless one of the ballpark’s selling points: Wonderful views of the U.S. Capitol and the Washington Monument, two of the city’s tallest architectural icons. As both the cranes and first of the nearby structures took root, those views fast became obliterated. Despite the Capitol Riverfront having grown full flower, the monuments can be seen from the ballpark—but you have to know where to go to look. The U.S. Capitol is best viewed behind Section 401, the last section atop the upper deck along the left-field line; the Washington Monument is mostly visible to fans seated high up the upper deck near the right-field foul pole.

The obscured views must have had the architects and politicians wondering if Nationals Park would have been better served being rotated 90 degrees to face the Anacostia River, with the home plate gate more naturally accessible to the bulk of fans arriving from the north. Perhaps there was initial reticence over facing a horribly polluted river, but even the Anacostia has since had its act cleaned up—a long-overdue, environmental triumph that’s part of the Capitol Riverfront’s rejuvenation.

Through much of Nationals Park’s first 10 years, cranes and emerging residential/office hi-rises were a common sight. The Capitol Riverfront district surrounding the ballpark flourished from a crime-ridden industrial area to one of Washington’s hippest—and gentrified—neighborhoods. (iStock)

Red, White, Blue and Green.

The Anacostia is kept safe thanks in part to Nationals Park’s above-and-beyond efforts to ensure best-practice green sustainability. Stormwater from frequent summer rains captured at the ballpark goes through a rigorous filtering system that separates unwanted refuse and chemicals from flowing into the river. Nationals Park itself was built mostly using recycled steel, while 5,500 tons of construction waste were also reclaimed. A food court behind left field sits under a 6,300-square foot green roof, where an assortment of vegetables and herbs are grown to supply ballpark concessions. Beer cups are biodegradable. The light standards that rim the top of the ballpark face downward to limit light pollution. Solar panels top both parking garages at the ballpark’s north end. And Nationals Park is the first major league ballpark to use reverse vending machines, where fans can deposit used aluminum cans and plastic cups and, in return, receive “rewards” (which apparently vary).

Sustainability was not foremost in the minds at the start of the project, but HOK Sport’s Susan Klumpp Williams—a LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) accredited professional—willed it through the process. Her efforts paid off; Nationals Park was the first LEED-certified green pro sports venue, and Travel + Leisure magazine named the ballpark, when it opened in 2008, as one of the nation’s top 10 green landmarks.

Stephen Strasburg embodied the rebirth of the Nationals during the 2010s. In one of the most memorable games played at Nationals Park, Strasburg struck out 14 Pittsburgh Pirates in his 2010 major league debut; nine years later, he earned World Series MVP honors as the Nationals won the franchise’s first-ever championship. (Flickr-Lorie Schall)

From High Times to Hard Times.

Like the stars and planets aligning, the Nationals, the ballpark and the surrounding area all kicked into high gear in the 2010s. First-round picks Stephen Strasburg and Bryce Harper proved to be the real deals, achieving All-Star status and fronting a team that also included flamethrowing ace Max Scherzer and offensive threats in speedster Trea Turner and, by decade’s end, the arrival of a second wunderkind with teenaged Juan Soto. Fans responded and began filling up more of Nationals Park’s seats—even the expensive ones behind home plate. And the Capitol Riverfront neighborhood was finally booming with full-steam-ahead energy, as empty lots began getting gobbled up by sparkling new developments at an accelerated rate. There was little controversy between the Nationals and the city at this time, except in 2013 when the team wanted to throw a $300 million retractable roof over Nationals Park and find out if the city would be stupid enough to pay for it. The city was not; D.C. mayor Vince Gray all but laughed the Nats out of his office.

The 2010s are best remembered for some of the ballpark’s greatest moments. Strasburg introduced himself to the Nationals, their fans and the baseball world in June 2010 with 14 strikeouts against the Pittsburgh Pirates. Jordan Zimmermann threw the ballpark’s first no-hitter in 2014, followed in 2015 by another from Scherzer—who missed out on a perfect game when he hit the 27th batter. A year later, Mad Max performed another stunning feat when he struck out 20 Detroit Tigers. In 2017, Anthony Rendon racked up six hits (including three home runs) and 10 RBIs in a 23-5 drubbing of the New York Mets—who in 2018 were boat-raced in an even bigger rout when the Nats put up a ballpark-record 25 runs upon them. That same year, the All-Star Game came to Nationals Park, and the venue praised for being fair to both pitchers and hitters became a bandbox for a night as a Midsummer Classic-record 10 home runs were smashed over the fence. Turner, in 2019, hit for his first of two cycles at Nationals Park (he would also have a third one for the Nats, on the road).

The 2019 season, in particular, would be the sweet capper to, that point, a bittersweet decade in which the Nationals ran off seven straight winning records—but failed to win any of four postseason series. Reviving back to life after an awful (19-31) start, the Nationals bounced back and into postseason as a wild card, startlingly rolled through the NL playoffs, then grabbed the franchise’s very first World Series trophy by edging the highly-favored Houston Astros in seven games—all of which were won by the road team. Though the Nationals won the clincher at Houston, Nationals Park was alive and bursting into cheers as 16,000 fans showed up to watch the game together on the big video board.

The Nationals’ championship momentum would be badly stunted in the 2020s, starting with the devastating 2020 COVID-19 pandemic that shut down social activity everywhere. In a sign of the times, a truncated 60-game schedule kicked off at Nationals Park in late July when U.S. chief medical advisor Anthony Fauci, a huge Nats fan clad in a face mask with the team’s logo upon it, threw out the ceremonial first pitch before a crowd of no one except a handful of team employees, photographers, and a sea of cardboard cutouts—including one section filled up with photographed likenesses of Juan Soto’s extended family. At the height of the COVID outbreak, Nationals Park’s many concessions kitchens were utilized by renowned chef Jose Andrés, who called the ballpark a “field of hope” as he prepared free food for those economically battered by the pandemic. The venue was later used as a mass vaccination site in the hope that all would soon return to normal.

A year later, the fans would be back, even as COVID did its best to hang on; the season’s opening series at Nationals Park with the Mets in town was completely called off due to a last-gasp viral outbreak in the Nationals’ clubhouse. As the pandemic waned, financial issues soon took center stage as the Nationals, underperforming for a second straight season and burdened by a heavy load of deferred payments, initiated a midseason selloff of talent in 2021—leading to the departures of Max Scherzer, Trea Turner, Kyle Schwarber, and many others.

Hard times were compounded by hard luck; the Nationals handsomely rewarded Stephen Strasburg after his 2019 postseason heroism with a seven-year, $245 million contract, and all they got out of it was eight appearances and a single win from the injury-flattened ace—while Patrick Corbin, another well-paid pitcher, stayed healthy but proceeded to become MLB’s worst pitcher of the early 2020s, posting a 33-70 record and 5.62 ERA before his contract finally expired in 2024.

Even young Juan Soto, who had quickly emerged into a massive offensive force in Washington, eventually had to go as the Nationals traded him to San Diego midway through 2022. The boatload of prospects the Nationals received from the Padres and other teams through all their talents-for-potentials deals did provide the foundation for a team that hopes to compete again.

Among the art to be enjoyed within Nationals Park’s concourses is this group of large circular mobiles called The Ballgame, featuring the illustrations of Walter Kravitz. (Flickr-Adam Fagen)

It’s Even Got a Whole Foods.

The transformation of the Capitol Riverfront neighborhood from its bad ol’ days to its current gentrified presence is all but complete. Development still continues on the few remaining empty lots, but Nationals Park’s influence upon the area has been unmistakable, exceeding the expectations of those who lobbied for the ballpark’s existence. Some 10,000 folks have taken up residence in the modern hi-rises, mostly north of the ballyard. Restaurants and bars thrive at street level or amid rooftop lounges. A Whole Foods Market is part of the scene, as is Audi Field, a 20,000-seat stadium for MLS’ D.C. United located a couple blocks southwest of Nationals Park. The nearby Anacostia River is flowing healthy again, attracting weekend boaters.

There have been growing pains, as unwanted memories of an area once considered very dangerous have occasionally come back to brief life. A 2013 game at Nationals Park was postponed after a mass shooting at the nearby Navy Yard claimed 12 lives. And during a Nationals-Padres game in 2021, a shooting outside of the ballpark’s left-field gate frightened a crowd of over 30,000; no one inside was hurt, as the fans were safely evacuated and the game called until the next day.

If you live outside of the Capitol Riverfront and plan to visit Nationals Park, take this advice: Don’t drive there. Parking is virtually non-existent around the ballpark, except for the twin garages within the facility usually reserved for season ticket holders. There are plenty of convenient mass transit options, the most popular of which is the Metro rail system with a stop just two blocks northeast of Nationals Park’s center-field gate. You can also ride Metrobus right up to the ballpark’s curbside, or even a ferry along the Anacostia from Alexandria, Virginia, with a short walk from the dock to the first-base gate.

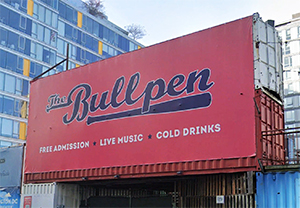

However you get to Nationals Park, you owe it to yourself to get there early and enjoy what the Capitol Riverfront has to offer for a pregame experience. The Bullpen, one of the very first establishments to open in the area just a year after Nationals Park opened, clings to its industrial roots as an outdoor venue offering food, drinks and entertainment, emitting a block-party vibe amid a collection of large shipping container boxes. Down at the corner of South Capitol and North Streets, across from Nationals Park’s northwest corner, is Walter’s Sports Bar—which doesn’t sound too baseball-ish until you remember, oh yeah, Walter Johnson. On the other side of the ballpark, among a collection of riverside restaurants/bars, is the Salt Line, which specializes in oysters and beer—and includes longtime Nationals favorite Ryan Zimmerman as one of its investors.

A planned extension of the Nationals’ lease—keeping them at Nationals Park through 2054—includes funding to upgrade the look and feel of the ballpark. This rendering, among a number ordered up by the Nationals, shows an updated main gate and mod coverings of the aesthetically assailed parking garages. (Washington Nationals)

The Future is Calling—But How Long Will It Last?

Nationals Park has sailed through nearly two decades with little alterations. That may be about to change. With the bonds used to fund the ballpark expected to expire a full 10 years early in 2027, the D.C. Council—a completely different cast of characters than the group that fought both MLB and itself back in the 2000s—was set to dangle another $350 million in front of the Nationals for upkeep and upgrades. The catch: The team had to agree on extending its lease at the ballpark 17 years through 2054. The Nationals have not yet said yes, but they certainly seem more than interested; they’ve released renderings of an improved Nationals Park—mostly focusing on an aesthetically revamped north end of the park with a redone center-field gate and decorative tan wrapping of the twin parking garages, the base of which is planned to include more retail shops.

There also may soon be a change on the marquee. Over Nationals Park’s lifespan, the Nationals have chronically mentioned seeking out a naming-rights sponsor to retitle the ballyard in exchange for money, but nothing has ever come of it. Why the team hasn’t come up with a deal and remains in the minority of MLB ballparks without one seems to be something of a head scratcher, considering it could use the money and a bump in the standings. Sources say the Nationals are looking for a corporate partner that shares their values and agrees to the right price.

The Nationals are understandably cautious on this matter. In 2022, they agreed to a five-year, $38 million deal with crypto company Terra to splash its name on the ballpark’s high-priced seats and exclusive club behind home plate. The team collected all of its money from Terra up front, which ended up being a highly fortuitous move; within two years, Terra’s finances collapsed, its founder arrested, and bankruptcy declared. Yet the Nationals are living up to their end of the deal, allowing a dead company to continue splashing its name within easy eyeshot of TV cameras.

The memories of what Nationals Park could have gotten right linger within some like a mild form of post-traumatic stress. Yes, the District of Columbia could have found something better to spend nearly $700 million on. Yes, the twin parking garages would look better unseen, underground. Yes, the damn thing doesn’t have to look like an office building from the outside. But Nationals Park has given Washington baseball fans something to at long last embrace, making memories of Griffith Stadium’s mindless incongruity and RFK Stadium’s multi-purposed compromises less palpable and more nostalgic.

The 21st Century has put D.C. Baseball and the Capitol Riverfront community in a far better place thanks to Nationals Park and those in local power that toiled, argued and, in some cases, sacrificed their political careers to make it happen.

In the end, they all get points for the effort.

The Ballparks: Griffith Stadium Your ballpark has burnt to the ground and you’ve got three weeks before Opening Day. Quick—whaddyado? Ask the Washington Senators, who performed the ultimate rush job and constructed Griffith Stadium as one of the more architecturally coarse and confusing of venues, with a playing field so distant and awry, the whole outfield became Triples’ Alley. Fans and presidents were nonetheless thrilled by the breathless action between the lines.

The Ballparks: Griffith Stadium Your ballpark has burnt to the ground and you’ve got three weeks before Opening Day. Quick—whaddyado? Ask the Washington Senators, who performed the ultimate rush job and constructed Griffith Stadium as one of the more architecturally coarse and confusing of venues, with a playing field so distant and awry, the whole outfield became Triples’ Alley. Fans and presidents were nonetheless thrilled by the breathless action between the lines.

The Ballparks: RFK Stadium Built by the Federal Government on the same straight line that’s home to the U.S. Capitol and other historic American landmarks, RFK Stadium was conceived to enjoy a similar, lofty stature—and even though it was hog heaven for football fans, it became a fractured limbo for the baseball gods who suffered few ups and many downs within the venue’s roller coaster-shaped rooflines.

The Ballparks: RFK Stadium Built by the Federal Government on the same straight line that’s home to the U.S. Capitol and other historic American landmarks, RFK Stadium was conceived to enjoy a similar, lofty stature—and even though it was hog heaven for football fans, it became a fractured limbo for the baseball gods who suffered few ups and many downs within the venue’s roller coaster-shaped rooflines.

Washington Nationals Team History A decade-by-decade history of the Expos/Nationals, the ballparks they’ve played in, and the four people who are on the franchise’s Mount Rushmore.