The Ballparks

Griffith Stadium

Washington, D.C.

Your ballpark has burnt to the ground and you’ve got three weeks before Opening Day. Quick—whaddyado? Ask the Washington Senators, who performed the ultimate rush job and constructed Griffith Stadium as one of the more architecturally coarse and confusing of venues, with a playing field so distant and awry, the whole outfield became Triples’ Alley. Fans and presidents were nonetheless thrilled by the breathless action between the lines.

In every American neighborhood, among the continuity of neat and finely polished homes, there always seems to be that one house that ruins the rhythm. Whether it’s an odd shape, unique character or unkempt front yard, it runs against the flow of its surroundings, whether by design or not.

Which brings us to Griffith Stadium. Baseball’s golden era of steel-and-concrete ballparks is remembered, more than not, for its stylish, dignified facades. But Griffith’s fortified hodgepodge clearly represents the “not,” the contrariety, on the list. With its zig-zaggy ingresses, nonsensical structure hierarchy and a playing field so out of whack that it resembled a toddler’s mindless stab at a connect-the-dots puzzle, Griffith Stadium looks as if it could have been created by the set designers behind The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari.

A place like Griffith, lacking the touch of palatial baseball elegance found among so many other new ballparks of the time, would seem an unlikely place for the President of the United States to show up every Opening Day and throw out the ceremonial first pitch—especially when the venue’s owners, the Washington Senators, were more lousy than not. But tradition is tradition, the White House was only two miles away, and so it was as convenient a place as any for Commanders in Chief to pay their respects to the National Pastime.

For the Senators’ diehard fans—and they died hard often, watching their team continuously sink in the standings—Griffith Stadium was fine enough. The views were exemplary, and spectators bore witness to a unique form of baseball entertainment, especially when exhausted outfielders chased long triples into the distant left-field corner or tried to avoid playing pinball with the tall, multi-angled right- and center-field wall. Washington may have been first in war, first in peace and last in the American League, but Griffith Stadium was #1 in the hearts of D.C. baseball fans who happily put up with the park for 50 years.

A Legacy to Disavow.

Trying to make baseball work in Washington during the 19th Century was like trying to succeed with that little shop in the remote corner of the shopping mall where no one ever went: Many different owners, same sorry results. There were seven separate D.C.-based major league teams in the 1800s, and they were all bad. So bad, that not one of them ever enjoyed even one winning season. In fact, they combined to lose two games for every one they won. Translated to a modern 162-game schedule, that’s a 54-108 record.

The ballparks these teams played in were just as numerous and short-lived. No less than eight different facilities were used over a 30-year period, almost all of them small, wooden and visually bland. One managed to make it intact out of the 19th Century: National Park, built and used by the National League’s Washington Nationals from their 1892 debut. But it became a ballpark without a team in 1899 when the Nationals, along with three other weak NL franchises, were ordered shut down by the league.

In 1901, the newborn American League tempted fate by trying big league ball once more in the Nation’s Capitol. Sure enough, the Washington Senators continued the tradition of crash-and-burn D.C. baseball through their first decade of operation, averaging 100 losses a year without once finishing above .500. But at least they were surviving, as the majors in general were at long last enjoying an unsurpassed stretch of stability. Finding a facility to call their own, however, became a challenge; the National League, at virtual war with the AL, refused to allow the Senators to use National Park. When the two circuits eventually smoked the peace pipe, the Senators were finally invited in, expanding the park from 6,500 seats to 10,000.

As Griffith Stadium’s wooden, ancestral incarnation, National Park would yield its share of interesting quirks. Early in its lifespan, large trees hung over the outfield fences and often interfered with fielders trying to catch deep fly balls. Wildcat bleachers, a somewhat common and often nagging (for team owners) sight at many major league facilities of the time, were erected on the tops of houses behind right field. And out in deep center lay a doghouse that served as place to store the ballpark flag; a ball was once lined through its open door, and Philadelphia Athletics outfielder Socks Seybold went in to retrieve it—only to get half his body stuck inside. It took several minutes for teammates to pry him out.

Action during the 1924 World Series, the first and only one ever to be won by the Washington Senators. Note the extended height of the recently added grandstand down the left-field line, as opposed to the original grandstand that ran between first and third base. (Library of Congress)

A Slapdash Phoenix.

While the Senators were at spring training readying for another lousy campaign in 1911, a plumber doing work on National Park apparently lost control of a blowtorch. Result: The whole place went up in flames. Suddenly without a ballpark less than four weeks before Opening Day, panicked Senators management had no choice but to forge a replacement at 24/7 speed, wisely opting for steel and concrete over wood; somehow, a single-decked, roofless 16,000-seat facility sprang up just in time for the scheduled first pitch. “Day and night,” the Washington Star reported, “the chanting of the Negro laborers had been heard in the vicinity, like Aladdin’s palace, the structure rose as if by magic.” Hopefully for those builders, the wages were worth the effort.

Work on the rebuilt ballpark continued through the 1911 season and wrapped in late July, revealing a finished product that sat 27,000 and consisted of a double-decked, covered grandstand barely stretching around the infield, with an uncovered single deck extending down each line. Because of the rush to get it built, the Senators and Osborn Engineering, the preeminent ballpark designer/builder of the day, had no time (and probably little money) to add elegant character to the exterior, as was done with Philadelphia’s Shibe Park and Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field, both built just a few years earlier. Because of the disharmony created by multiple long ramps and other detached small structures randomly dotting the open space behind the first base side of the ballpark, any chance to give the ballpark a formal palatial façade would have required a massive facelift down the line. And as the Senators penny-pinched their way through time, that was never going to happen.

By 1923, the ballpark still referred to as National Park (and sometimes American League Park) would be renamed Griffith Stadium after the man who would become the face of the franchise, Clark Griffith. A seven-time 20-game winner who thrived on the mound circa the Turn of the Century, Griffith would move on to managing and eventually take over the Senators’ reins during the 1910s. With the help of the remarkable Walter Johnson in his prime, Griffith finally gave Washington baseball fans a winning team to follow, even if on an occasional basis.

Called the Old Fox for his stern disposition and quickly graying hair—the New York Times’ Kevin Dowd once wrote that he looked like a “grandfather in a Frank Capra movie”—Griffith in 1920 bought controlling interest in the Senators and, over the next decade or so, gradually oversaw expansion of the ballpark that essentially resulted in its final look. The major additions consisted of double-decking the bleachers down the lines to match the existing two-level grandstand behind the infield—but in sync with Griffith Stadium’s historical lack of rhyme and reason, they didn’t match. Instead, the outer structures were angled at a steeper pitch—with a roofline 15 feet higher than the original grandstand—and were joined together at the front, but not at the back.

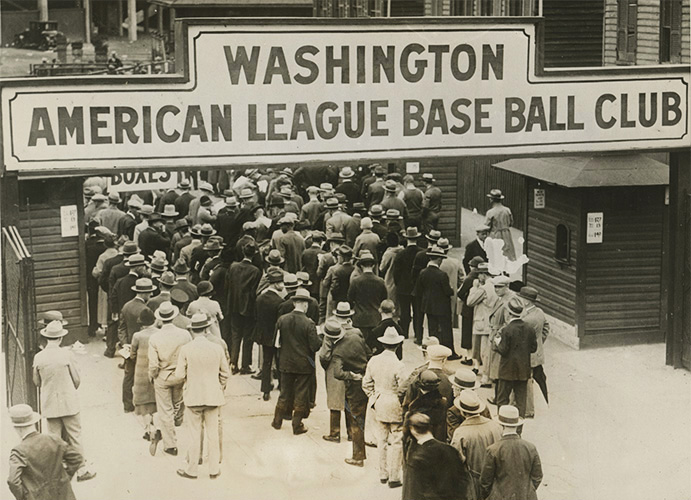

Fans file through Griffith Stadium’s plainly explained main entrance in 1925. Once past this area, one still had to traverse up a long ramp over a barren inner plaza to reach the actual ballpark. (The Rucker Archive)

Have a Safe Triple.

The utter asymmetry of Griffith Stadium’s architecture had nothing on the asymmetry of the playing field, which expanded outward in all directions until it could go no further. The end points led to some wacky dimensions. In right field, a tall wall measuring 31 feet in height—just six feet shorter than Fenway Park’s famed Green Monster—was erected in front of an alleyway and ran a straight line from the foul pole (320 feet from home) to right-of-center (a Herculean 457). The wall then made a sharp, 90-degree turn into the field—and then, 80 feet later, a second, equally sharp turn back toward Fifth Street, which ran behind left field. This ‘indent’ was created out of the refusal of a duplex owner behind center field to sell his land to the Senators—but in holding on to his territory, the landlord also maintained a beautifully huge oak tree that rose high behind the wall and gave the ballpark something of a vernal feel.

Then there was left field, which would bedevil right-handed pull sluggers for generations. The Senators built bleachers behind the (much shorter) left-field fence to perfectly align with Fifth Street, which angled away from the ballpark. Thus the left-field foul pole would lie 407 feet from home plate—giving the ballpark the unusual circumstance of a longer poke down the line than to the nearby left-center gap (at 391 feet). Between the tall wall towering over right and center, and the mind-bending spaciousness of left, deep flies rarely turned into home runs—but it did result in a whole lot of doubles and triples.

With the ballpark’s expansive outfield, Clark Griffith strategized a roster strong on speed and line drive tenacity; classic home run hitters need not apply. The splits were telling. In 1924, the year the Senators won it all for the first and only time during their long stay at D.C., they hit just one home run at Griffith. They did it again in 1945, and that was an inside-the-park job. Goose Goslin, the Hall-of-Fame outfielder who was the Senators’ closest thing to a home run threat, went deep 17 times in 1926—all of them away from Griffith Stadium. It wasn’t until 1936 that someone homered twice in one game, when Cleveland’s Hal Trosky sent two over the right-field wall.

What Griffith Stadium lacked in home runs, it made up for in triples. Remember last paragraph and the note about the Senators hitting just one homer at home? That same year, they racked up 61 triples at the ballpark. Sam Rice, the all-time franchise leader in runs, hits, doubles and triples, collected at least 10 three-baggers in 10 straight seasons—almost two-thirds of them coming at Griffith. The powerful Goslin, in 748 career games at the ballpark, could only manage 38 home runs while legging out 89 triples. And in 1933, the Senators as a team became the last major league team to date—and likely forever—to post 100 triples in a season, with the expected majority of those collected at home.

Break Out the Measuring Stick.

Remarkably, some of the game’s greatest sluggers managed to make Griffith Stadium look positively small. Early in 1953, The New York Yankees’ Mickey Mantle launched what’s undoubtedly the ballpark’s most famous home run when he smashed a ball over the fence, all 32 rows of the left-field bleachers, nicked the side of the National Bohemian Beer billboard above, crossed Fifth Street and finally came to a stop in a backyard several houses down Oakdale Place. In attendance, Yankees P.R. man Red Patterson left the ballpark, found witnesses outside and eventually the ball, paced the distance back and came to the conclusion that it had traveled 565 feet from home plate. What’s lost on many of those familiar with the event is that the ball didn’t actually cruise 565 feet on the fly—it bounced to its final resting spot—yet Mantle’s bash made for instant legend because the mathematical guesswork involved was a novice thought and gave birth to the concept of “tape-measure” home runs.

Patterson apparently didn’t have his ruler on hand exactly three years later on Opening Day when Mantle very possibly outdid himself at Griffith—twice. He crushed two balls to center field; one clipped the massive oak tree behind the wall and fell on Fifth Street, the other cleared the tree and landed on a rooftop across from Fifth. The aerial distance of each blast had to range between 550 to 600 feet.

In June 1949, former Negro League star and future Hall of Famer Larry Doby, emancipated with the Cleveland Indians, struck a ball that cleared the (other) National Bohemian billboard atop the main scoreboard high over the right-center field wall and landed atop a house in the alleyway behind, over 500 feet away. According to The Sporting News, an irate homeowner got on the horn with the Senators to complain. “Somebody from your park just threw a baseball onto the roof of our house and woke up my children and now I can’t get them back to sleep,” she said. “You’ll have to stop it.”

Doby was not the first African-American to show prodigious power at Griffith Stadium. During the 1940s, the ballpark was the partial home of the Negro League’s Homestead Grays, who also played at Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field when the Pirates weren’t in town. Among the many legends on the Grays’ roster was Josh Gibson, the so-called “black Babe Ruth” who was no stranger to monster home runs. Negro League statistics are fleeting and tales from witnesses often tall, but it’s believed that Gibson hit at least one, and maybe two, balls over Griffith’s left field bleachers. It so impressed Clark Griffith that he entertained the thought of signing Gibson to the Senators before Jackie Robinson inked with the Brooklyn Dodgers—but any chances of Gibson being brought on board after Robinson’s debut vanished when he died of a stroke at age 35.

Tinker Tailor Solder Sigh.

To accommodate the majority of major leaguers who possessed more mortal power (or none at all), Clark Griffith continuously toyed with moving in the distant fences in left. He did so twice, in 1946 and 1950—from 407 feet down the line to 375 and 388, respectively. In both cases, Griffith quickly moved them back—sometimes in midseason—because he discovered visiting teams were able to take more advantage of the shorter dimensions than his Senators, who he had built to sear line drives into the gaps and not over the fences.

In the Senators’ rare run of good times—a 10-year period from 1924-33 that yielded eight winning records, three AL pennants and, in 1924, their lone World Series title—Griffith found another way to reduce field dimensions: By adding temporary seats deep in the outfield. The maneuver was more about revenue than runs, and was a common tactic utilized by many World Series participants of the time; it seemed to make sense at Griffith Stadium, which was often criticized for having too much outfield real estate anyway. Sometimes it helped the Senators; in the 1925 World Series against the Pirates, Goose Goslin bounced two line drives into the temporary seats and was granted home runs per the ground rules. Sometimes it didn’t help; Mel Ott’s 10th-inning fly ball into the temps officially resulted in a solo home run that won Game Five and the 1933 Fall Classic for the New York Giants over the Senators.

The First Fan.

One of Griffith Stadium’s more permanent seat was the Presidential Box. Located near the first base dugout, the special seat was reserved for American presidents and other dignitaries who apparently had nothing better to do than to watch the Senators lose. The Commander in Chief’s ceremonial first pitch on Opening Day was the ballpark’s most hallowed and longstanding tradition, with everyone from William Howard Taft to John F. Kennedy pitching in. There was usually no catcher to formally take the throw; players ganged up and fought for the ball, like ladies trying to catch the bouquet of roses at a wedding reception.

Audience receptions afforded to the president varied depending on the politics of the day. Harry S. Truman threw out the first ball in 1951 to a mix of cheers and boos, the latter from those upset that he had fired General Douglas MacArthur earlier in the day.

Security, as one might expect, got tighter and tighter around the Presidential Box as time went along. For Opening Day 1954, it was reported that the Secret Service had a “dossier” on everyone sitting within 100 feet of President Eisenhower for the Senators’ home opener. The stress of preventing a potential global incident is probably what kept Cuban dictator Fidel Castro from taking a seat in the box in 1959, after the Senators extended an invitation to him; they probably rescinded it anyway after Castro was seen in New York City hugging Soviet Union premier (and American arch-foe) Nikita Khrushchev in public.

Shots were once fired at Griffith Stadium, if you believe what the Chicago Tribune’s Ed Burns wrote long ago. According to his account, a nearby resident reportedly high on heroin took to his rooftop with a rifle and decided to see how close he could shoot at Chicago White Sox pitchers hanging out in the visiting bullpen without hitting them. Fortunately, his aim was accurate enough that no one got shot, but the White Sox’ Ted Lyons recalls hearing bullets whizz past his ears.

President Woodrow Wilson throws out the ceremonial first pitch at Griffith Stadium’s 1916 home opener. The presidential pitch was one of the ballpark’s most revered traditions. (Library of Congress)

The Big Train at Full Speed.

Early on in Griffith Stadium’s existence, presidents did expect a Senators win. There was one very good reason for this: Walter Johnson. The tall, amicable Hall-of-Fame pitcher, armed with one of baseball’s great fastballs, was always given the starting assignment on Opening Day at Griffith—and he almost always pitched at his very best for the occasion. After catching the first presidential first pitch from William Howard Taft in 1910 when Griffith Stadium was still wooden National Park, Johnson went out and dealt a one-hit shutout. He would also throw Opening Day shutouts in 1919 (a 13-inning gem), 1924 (a four-hitter) and 1926, when at the age of 38 he logged 15 remarkable innings and emerged with a six-hit, 1-0 victory that was the 398th of his career. The victims in all four games: The Philadelphia Athletics.

Though official splits stats are tough to come by in the early years of Johnson’s career, it’s readily apparent that the bulk of his 417 career victories took place at Griffith Stadium; his earned run average at home from 1913 on was a sensational 2.05. Of the 110 shutouts he threw—more than anyone else collected, ever—73 took place at Griffith. In 1918, he chalked up a streak of 51 consecutive scoreless innings pitched at home, the second longest run by a pitcher in one ballpark. Throughout his 21 years as a Senators pitcher, Johnson experienced the franchise’s deepest lows—he suffered through a 1909 campaign in which Washington finished 42-110, posting a 13-25 record despite a strong 2.22 ERA—and its stratospheric highs when, as a career sunset loomed, he finally got to taste championship glory in 1924. “The Big Train” was so revered by the team and its fans, he became one of two individuals—Clark Griffith being the other—to be eternally honored when, in 1947, a memorial was erected at Griffith Stadium. It can be seen today at a high school named after him in Bethesda, Maryland. (Clark Griffith’s memorial, created in 1956, was moved to RFK Stadium where it remains today.)

Tinker Tailor Solder Sigh (Continued).

Clark Griffith continued to subtly modify his ballpark through time, with wishy-washy force. Apart from tinkering with the field dimensions, he moved the bullpens here, there and everywhere; sometimes it was behind the shortened left-field fence, and before long it was situated in the deepest part of right-center, with a short fence surrounding it (similar to the bullpen area behind right at Boston’s Fenway Park).

Griffith also ran hot and cold on lights. He originally decried night baseball as “synthetic” and swore he’d never put up lights, but by 1941 he was all in on the concept and then some, at one point furiously lobbying fellow owners to play two straight months at night during the summer. (The owners shook their heads no.)

One night game at Griffith Stadium produced a bit of a chuckle when the lights went out just as a pitch was being delivered to the Detroit Tigers’ George Kell. When they came back on, seconds later, fans were amused to find all of the fielders and umpires lying flat down on the playing field. Why? Because they had no idea whether Kell had swung, and didn’t want to take a chance on getting hit by a line drive in the dark.

The Senators drew well at night and helped to bring in more revenue into Clark Griffith’s coffers, but he also made out well by keeping the ballpark occupied even when the Senators weren’t in town. Boxing and wrestling events were a common sight during the summer, with the most memorable bout being the 1941 heavyweight fight between Joe Louis and Buddy Baer. In the fall, football took over; when the Senators’ season was done, temporary bleachers were hoisted up in right field that gave Griffith Stadium a larger capacity at 35,000. The ballpark was used by numerous local college teams and, from 1937-60, was home to the NFL’s Washington Redskins—whose most famous game at Griffith is likely the one they’d want everyone to forget: The 1940 NFL Championship, won 73-0 by the visiting Chicago Bears. That blowout remains the largest margin of victory in pro football history.

The view from one of Griffith Stadium’s best seats in the house, in 1958.

After the Fox.

The Old Fox wasn’t going to live forever. In preparation for the inevitable, Clark Griffith had groomed nephew and adopted son Calvin for decades—having him do everything from selling peanuts to serving as the team’s bat boy to running the farm system (not all at the same time, of course). When Clark passed away in October 1955 at age 85, Calvin took over the franchise and began to instill a more modern approach for the Senators and Griffith Stadium. He killed two birds with one stone in 1956 by at long last bringing in the left-field foul pole to a more sensible 350 feet from home plate; with added spectator space created behind, he next went against the prohibitionist dogma of his late father and established a beer garden, with the help of D.C. officials finally loosening on alcohol restrictions at public events. (Beer consumption was restricted to the garden until 1959, when it was made available throughout the entire ballpark.)

The reduced dimensions shot home run totals through the roof. The Senators, who as a team were normally lucky to hit 20 homers a year at Griffith, suddenly banged out 63 at home in 1956. Among those falling in love with the cozier measurements were Roy Sievers, who with 42 homers (26 at home) in 1957 became the first player in franchise history to lead the AL in round-trippers; and a young Harmon Killebrew, who two years later became the second when he blasted 42—22 of those at Griffith.

Despite the newfound appearance of muscle, the Senators continued to lose. For the entire 1950s, they managed only one winning season (and barely, with a 78-76 record in 1952) and never finished any higher than fifth in the eight-team AL. The Senators’ embodiment as eternal losers rose to a pop cultural level as Broadway staged the successful musical Damn Yankees!, about a demoralized Senators fan named Joe Hardy who sells his soul to the devil to be reincarnated as the team’s star savior and help knock off the dynastic Yankees. Hollywood followed suit with a film adaptation, as Warner Brothers brought seven cameras into Griffith Stadium to capture the scene at a real Senators-Yankees game—paying each player, coach and trainer present $100 for being an “extra.”

The more Calvin Griffith settled into his role as the Senators’ new lord, the more restless he became over the franchise’s long-term prospects in Washington. Even as thousands of Joe Hardys gradually gave up and emptied out of Griffith Stadium, the Senators managed to remain in the black by securing all concessions revenue along with healthy TV-radio income and continued rental of the facility for other events. But the writing on the wall was looking more and more legible—and troublesome. Griffith bemoaned the everyman’s increased dependence of automobiles and thus the increased headache of trying to reach and park at the ballpark, situated far and away from any major expressway. He also fretted over a new multi-purpose stadium being planned by D.C. officials; either he could embrace it, pay rent and take a far lower cut of the revenue, or he could stay at aging Griffith Stadium and likely lose all the rental income from folks, like the Redskins, who were salivating to take their business to the new facility. Finally, there were the newly arrived (from St. Louis) Baltimore Orioles, sucking away fed-up Senators fans 40 miles to the north.

In the meantime, Griffith began taking calls from other cities thirsting for big league baseball. Los Angeles officials phoned first before Walter O’Malley elbowed in and convinced them that his Brooklyn Dodgers were a better option. Then came a full-court press from Minneapolis, which had a new, easily expandable ballpark, a sea of parking surrounding it and a sweetheart lease ready for the first team willing to grab it. Griffith publicly brushed off the Minneapolis effort, which began to make waves in 1957, as nothing more than a courtesy call—but privately, with each passing day, with every option to remain in Washington crippled with caveats, he realized it was a no-brainer opportunity.

There was also this: Griffith, who along with his father had restricted African-American fans to upper deck seats along the right-field line—the Senators brewed up a story that they obliged black fans who wanted their own section—didn’t dig the local preponderance of black people, most of them not very well off. Griffith made his feelings on the subject painfully clear years later when he told a Lions Club gathering in Minnesota why he left Washington: “I found out that you only had 15,000 blacks (in Minneapolis).”

Griffith Stadium’s gradual deterioration following its 1961 closure doesn’t hide the inelegance of its patchwork exterior, as shown here from behind the structure that ran along the right-field line.

Howard You Doing?

When the Senators left after the 1960 season to become the Minnesota Twins, Griffith Stadium received a one-year reprieve thanks to two developments. Baseball owners, paranoid that D.C. politicians would take their anger out on the Twins-nee-Senators by reopening the case against the game’s antitrust exemption, hastily filled the void by granting Washington with an expansion team, also to be named the Senators. Additionally, that new team would play one last year at the old ballpark as construction delays at brand new D.C. (later RFK) Stadium piled up.

Knowing he had a roster short on power, new Senators owner Pete Quesada decided to go nostalgic and moved Griffith Stadium’s left-field foul pole back to 388 feet. Quesada hoped for more triples and fewer home runs—and he got it. None of the other nine AL teams hit as many triples at home as the Senators (29) did at Griffith, and only one (the Kansas City A’s) hit fewer homers at home, and barely—33 compared to the Senators’ 34. The new Senators continued one long-lasting Washington baseball tradition, finishing their inaugural 1961 campaign second to none in the league with an even 100 defeats.

The last game ever played at Griffith Stadium, on September 21, 1961, ironically pitted the new Senators against the old ones, the Minnesota Twins, who won 6-3. A sparse crowd of 1,498 showed up, a figure that didn’t include Twins owner Calvin Griffith; he stayed back in Minnesota, fearing that an appearance in D.C. could get him subpoenaed by angry ex-Senators stockholders who never wanted him to leave Washington.

In 1964, Griffith Stadium was sold to adjacent Howard University, which badly needed the land for expansion. The ballpark was demolished a year later, and in its place the school built a hospital that remains today. The ghosts of baseball past have not been forgotten; there is, of course, the obligatory historical plaque outside the hospital, but inside, down a hallway in front of the Emergency Medicine room, a representation of home plate and the batter’s box has been painted to denote the very spot where numerous baseball greats once came to bat. All that physically remains of Griffith Stadium are some 1,000 seats, most of which were transported and used at Orlando’s Tinker Field, the Twins’ spring training home through 1990. That ballpark itself was torn down in 2015, and the Griffith seats were sold, $100 for a pair.

Griffith Stadium isn’t fondly remembered like other long-ago built ballparks because there’s no beacon of memory attached to it, like an elegant, formal façade or an ivied wall. It was an imperfect park, aesthetically common but structurally uncommon—and it’s all the more forgotten because two teams named the Senators left town ages ago. That’s a shame, because a place that frequently hosted presidents, witnessed greatness in Walter Johnson and taxed a loyal fan base with seemingly endless periods of losing deserved better.

The Ballparks: RFK Stadium Built by the Federal Government on the same straight line that’s home to the U.S. Capitol and other historic American landmarks, RFK Stadium was conceived to enjoy a similar, lofty stature—and even though it was hog heaven for football fans, it became a fractured limbo for the baseball gods who suffered few ups and many downs within the venue’s roller coaster-shaped rooflines.

The Ballparks: RFK Stadium Built by the Federal Government on the same straight line that’s home to the U.S. Capitol and other historic American landmarks, RFK Stadium was conceived to enjoy a similar, lofty stature—and even though it was hog heaven for football fans, it became a fractured limbo for the baseball gods who suffered few ups and many downs within the venue’s roller coaster-shaped rooflines.

The Ballparks: Metrodome Ugly, cheap and purely artificial, the Metrodome reigned as the Yugo of ballparks, a synthetic spit at yesteryear with fake grass, fake wind and a bed sheet for a roof. While it kept out the rain, snow and red ink, it couldn’t prevent a flood of insults from just about everyone who entered through its wind-blasted revolving doors. Yet no team enjoyed a better home advantage than the Twins, who excelled within the venue’s occasional ear-shattering din.

The Ballparks: Metrodome Ugly, cheap and purely artificial, the Metrodome reigned as the Yugo of ballparks, a synthetic spit at yesteryear with fake grass, fake wind and a bed sheet for a roof. While it kept out the rain, snow and red ink, it couldn’t prevent a flood of insults from just about everyone who entered through its wind-blasted revolving doors. Yet no team enjoyed a better home advantage than the Twins, who excelled within the venue’s occasional ear-shattering din.

Minnesota Twins Team History A decade-by-decade history of the Twins, the ballparks they’ve played in, and the four people who are on the franchise’s Mount Rushmore.