The Ballparks

Hubert H. Humphrey Metrodome

Minneapolis, Minnesota

(iStock)

Ugly, cheap and purely artificial, the Metrodome reigned as the Yugo of ballparks, a synthetic spit at yesteryear with fake grass, fake wind and a bed sheet for a roof. While it kept out the rain, snow and red ink, it couldn’t prevent a flood of insults from just about everyone who entered through its wind-blasted revolving doors. Yet no team enjoyed a better home advantage than the Twins, who excelled within the venue’s occasional ear-shattering din.

When one thinks of the average modern downtown ballpark, a series of visions follow. Beautiful. Nostalgic. Accessible. Expensive. A beacon for restaurants, bars, shops and chic residences.

The Hubert H. Humphrey Metrodome, renamed the Mall of America Field in its dying days, was never any of these things.

It wasn’t beautiful. Unless, of course, you consider a windowless beige structure with all the charm of a giant storage facility as some kind of wonderful.

It wasn’t nostalgic. The Metrodome was the classic anti-classic ballpark, with no palatial touches, no real grass, blasé electronic scoreboards, trash bags for outfield walls, and a fabric roof that replaced Minnesota’s beautiful summer sky with a prefab overcast.

It wasn’t quite so accessible, beyond the car. Mass transit, in the form of light rail, didn’t even show up next to the stadium until 2003.

It lacked the bling—the bars, restaurants and retail—that usually gravitate toward a ballpark. Hubert’s Bar and Restaurant was the only legit pre- and post-game source within a Kent Hrbek blast. The Metrodome was, however, an easy walk for employees of numerous medical facilities, county offices and power stations that surrounded the venue.

It wasn’t really downtown. All the aerial images certainly make the Metrodome look like it was nestled between surrounding skyscrapers, but as photographers will often tell you, depth of focus is a wonderful thing. Truth was, the Metrodome was stuck at the city’s southeast edge, a good eight blocks from the heart of downtown.

Finally, the Metrodome wasn’t expensive—which was a good thing. And bad. Bad, in that its austerity led to a modern but amenity-free facility. Good, very good, in that it didn’t burden taxpayers with millions or more in debt like so many of today’s newer ballparks. In fact, the Metrodome actually made money, roughly over $100 million, for the State of Minnesota during its 33-year lifespan. Say what you want about Minnesotans, a politically eclectic bunch: They don’t lose touch with their pocketbooks.

The Minneapolis Star Tribune’s Pamela Schmid took into account the good and the bad when describing the Metrodome as being “modest in its plainness” and holding an “unpretentious Midwestern charm.” But others weren’t anywhere near as diplomatic. The Baseball people, in particular—the writers, players and coaches—all teed off on a multi-purpose facility that had football more in mind. Author Peter C. Bjarkman called it “A space-age inflatable bubble at odds with all that is sacred to baseball tradition.” Curt Smith said it was “the American League’s all-time bust.” “A circus tent on steroids,” stated Diamonds author Michael Gershman. New York Yankees manager Billy Martin, participant of a thousand games at iconic Yankee Stadium, trashed the Metrodome as “a mockery to baseball. It should go down as the biggest joke in baseball history.” Colleague Bobby Cox agreed: “It’s a travesty. Hit the ball on the ground and it bounces over your head. Hit it in the air and you can’t see it.”

The Minnesota Twins certainly saw a lot of good in their 28 years of play at the Metrodome. They studied, practiced and mastered the challenge of the bouncy artificial turf hops and fly balls that easily got lost against the white fabric ceiling—while opposing fielders, with far less Metrodome experience, looked foolish and lost in pursuit of the ball. The Twins also benefited from stadium workers who blasted air from giant vents behind home plate that, perhaps, gave a little extra push to fly balls when they were at bat. And they embraced the fans who, in times of championship glory, cranked up the vocal chords in an enclosed facility from which sound had no means of escape, making life miserable for opponents who quickly made next-day appointments with the ear doctor.

Avoiding “Cold Omaha.”

The Metrodome’s bland, windowless exterior was broken up by a series of equidistantly spaced red piping, the function of which was to provide stress relief for cables holding up the air-supported roof. (Flickr—Jenni Konrad)

With the Houston Astrodome having proved that large-scale enclosed stadiums could work, the City of Minneapolis in 1969 first came up with the idea of a local domed facility for both the Twins and (more crucially, to get out of the cold) the Vikings. The proposed stadium, designed by local architect Robert Cerny, was unique in that it was attached to a multi-level parking garage that completely encircled the playing venue and would include dedicated on- and off-ramps to nearby freeways and city streets. One would have hoped that Cerny had enough engineering savvy to figure out how to dispel the carbon monoxide from all the cars arriving and exiting in such close proximity to the domed airspace.

Throughout the next four years, Cerny’s dome labored to get approved through layer after layer of local bureaucracy, and the light at the end of the tunnel appeared bright as it readied to clear the last hurdle, a taxation board that looked to have the minimum five votes to give the project a go. But one of those five had just gone through a marital breakup and was now living outside of Minneapolis—thus making him ineligible to vote. Minneapolis mayor Charles Stenvig, who wanted the stadium but refused to vote for it because he feared losing re-election from an electorate that was largely against it, washed his hands of any responsibility and decided it would be a better idea to let the public have its say. Stadium proponents, knowing how that story would end, retreated and vowed to fight another day.

The Twins and Vikings made sure that day came sooner than later. The leases for both teams at Metropolitan Stadium were up after the 1975 season, and they were making waves about leaving town. The Twins, under owner Calvin Griffith—already in the books for having made good on his threat to move the Washington Senators to Minnesota 15 years earlier—explored repacking for Seattle once the Kingdome was approved by lawmakers there. The Vikings, even as they evolved into one of pro football’s more consistent winners, still drew crowds under the NFL average every season at the sub-50,000 capacity Met.

State politicians, worried that a possible departure of the Twins and Vikings would render the Twin Cities a “cold Omaha” as long-time U.S. Senator Hubert Humphrey once put it, jumpstarted the stadium issue in early 1976. It took nearly two years for lawmakers to agree on the concept and funding, but the main question remained: Where would the new stadium be built?

Three options were considered. One was to stay in Bloomington and give Metropolitan Stadium a major upgrade. Another was to build an adjacent football-only facility and mildly polish up the Met for the Twins. The third was to construct something completely new elsewhere—but the tricky part was that it had to be built on land that didn’t require public funds to purchase it.

The Metropolitan Sports Facilities Commission, a group of seven geopolitically correct individuals from around the state, was formed and given the task of weighing eight different proposals within the Twin Cities region. Among the non-Bloomington sites, the most promising one came from downtown Minneapolis, where a chunk of land largely owned by Star Tribune publisher John Cowles Jr., backed by downtown business interests, would essentially be given away to meet the commission’s no-cost demands. Thus it didn’t take a rocket scientist to figure out why the newspaper would become such a loyal advocate for the downtown site; the cheerleading became so embarrassing for some of the Star Tribune’s writers that a group of them bought a page of ad space in the paper to publicly disavow themselves of the rah-rah coverage.

One thing the Star Tribune didn’t want to embrace was any poll taken of Twin Cities taxpayers to find out what site they preferred—because it was likely they would prefer nothing. Sure enough, a local TV station took on the task and discovered that a mass majority (82%) didn’t want a new stadium, whether it was in Minneapolis, Bloomington, St. Paul, Eagan, Coon Rapids or wherever. But the commission had the funding mechanisms in place and the power to vote, and it wanted a stadium. It narrowed down the list of candidates to two: Bloomington and Minneapolis. On December 1, 1978, the commission voted 4-3 for the latter.

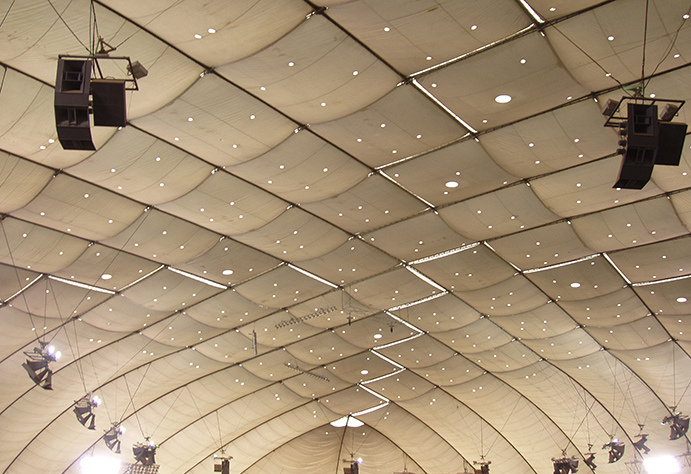

Looking up at the Metrodome’s air-supported roof reveals a star-like field of drainage holes; Dave Kingman once struck a pop fly right through one of them. (Flickr—Diz28)

Airing it In.

It was determined that in order for the new downtown stadium to be hospitable for Vikings fans in the winter—to say nothing of Twins fans in April or October—it had to be enclosed. Building a hard roof was going to cost more money than the budget had allowed, so the powers that be looked at a more recent trend in enclosure technology: The air-supported roof.

The concept of covering a venue with a synthetic roof and keeping it inflated with air “trapped” inside was the brainchild of designer Davis Brody and engineer David Geiger, who in 1970 built the first air-supported facility: The United States pavilion at Expo 70 in Osaka, Japan. From the air, the 460-by-262-foot roof looked like a giant mattress inserted into a concrete base, but it worked. Over the next 10 years, a number of big-time sports facilities—most notably the Tokyo Dome, the Pontiac Silverdome near Detroit and the Carrier Dome on the campus of Syracuse University—would be built using the technology. Like a balloon, air would be pumped in to keep the roof inflated; if it was accidentally let out or if the fabric tore, the roof would deflate to the ground.

The question was: How would fans enter and exit the facility without letting the air out? Enter the revolving doors. As anyone who’s ever gone through one knows, there’s no gaping exposure to the outside from the inside; the air that people take with them as they exit out is instantaneously replaced by air brought in through the other side of the door. So what is lost is quickly gained back. But not without fans having to endure a burst of air as they revolve through, sometimes knocking off hats and blowing hair in all directions. Bad hair days—or at least the appearance of them—would become a commonplace sight at the Metrodome.

David Geiger, who pretty much held the monopoly on the air-supported roof, was hired by the Metropolitan Sports Facilities Commission to design the Metrodome’s lid. In doing so, he made tweaks that would improve upon the earlier facilities using his technology. Thicker cables were arced higher to allow the roof to stand tall above the field (roughly 185 feet) and reduce contact from soaring pop flies; the added advantage to this was that the roof’s higher slope, in theory, would reduce any buildup of heavy snow above. To that end, there would be two layers of ceilings; the outer layer a Teflon-coated fiberglass, the inner layer built of fabric. Warm air would be pushed in between the layers to accelerate the melting of any snow atop the roof.

Finally, to reduce stress on the cables, compression rings were spaced roughly every 75 feet at the top of the seating bowl and connected to 12-inch steel “tiedowns” that were exposed outside of the structure and angled back down toward the foundation. Painted red, these tiedowns actually broke up the Metrodome’s otherwise drab exterior and gave it a subtle bit of aesthetic panache.

In October 1981, six months before the Twins were scheduled to inaugurate the Metrodome, 20 fans each whirling at 90-horsepower pumped in 250,000 cubic feet of air pressure per minute to raise the air-supported roof to its maximum height. Six weeks later, it all came down; the first heavy snowstorm of the season burdened the fabric’s structural integrity and tore it. The Metrodome roof’s first—but far from last—“oops” moment resulted in four days of repair.

The Metrodome otherwise sped toward completion, built under budget and on time; its publicly funded austerity was hardly a hush-hush secret, with MSFC lead Donald Poss admitting, “There has been more financial fat wrung out of this building than any building in this country of comparable size.” It was also apparent that the facility was designed to be more in sync with football than baseball. Its first-row seats would be situated high above the playing surface, a strange perception for baseball fans accustomed to watching at ground level; from there, the first deck would pitch up steeply, which at least would reduce the issue of having to crane one’s neck above any tall guy seated in front; and all seats would be positioned to aim toward the 50-yard line, not home plate.

Although Twins owner Calvin Griffith publicly praised the Metrodome by stating the team would “stop worrying about the weather,” he also fumed over the preferential treatment the Vikings seemed to be getting. Beyond the Metrodome’s football-friendly features, the 115 luxury boxes would also be controlled by the Vikings—never mind that the Twins would use the facility 81 times a year versus the Vikings’ 10-plus. And although the MSFC budgeted $1 million for the Twins’ team offices inside the stadium, it ended up going $700,000 over budget—and billed the overages to the Twins, causing Griffith to sue.

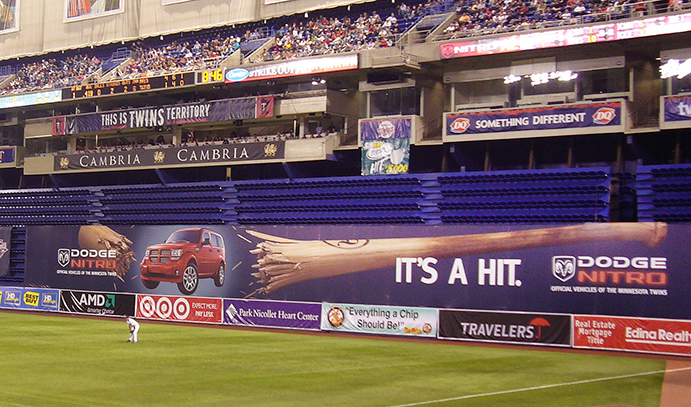

The infamous “Glad Bag” wall in right field, covering up 7,600 football seats folded up for baseball. Outfielders were frequently on edge, unsure of how a carom would rebound off it. (Flickr—Diz28)

Your Unflattering Synonym Here.

On April 3, 1982, spectators revolved through the doors, chased down their hats and re-combed their hair for the Metrodome’s first event, an exhibition between the Twins and Philadelphia Phillies—followed three days later by the official home opener before a crowd 52,279. Not all went well in the latter contest; the Twins lost to Seattle, 11-7, but fans situated in a luxury box had it worse as they were nauseated to see a stream of raw sewage flowing through their door after 40 toilets across the concourse had overflowed.

For those otherwise unaffected and enjoying the action within the indoor warmth, the Metrodome had already earned its stripes; the outdoor temperature for the exhibition was 19 degrees, and 28 for the season opener. But once summer came along and the mercury rose well above room temperature outside, there was nothing to counter against it within the Metrodome—because air conditioning hadn’t been built into it. By August, the unchecked heat had reached 90 degrees inside—prompting the Vikings to sue the MSFC on the eve of their first exhibition game at the facility. Their legal concerns became justified when 15 fans at that first game were treated for heat exhaustion.

For the Twins and their fans, the summer heat was among the least of their concerns. Everywhere you looked, there was something to criticize—and it led to enough unflattering synonyms for “Metrodome” to take up a whole page of Roget’s Thesaurus.

Large gatherings elbowed through tight concourses. Reporters had to sidle behind those seated in a claustrophobic press box. Players were forced to climb 44 steps up a stairway from the dugout to get to the clubhouse. Fans seated in the lower rows of the left-field bleachers had to fight glare from a six-foot Plexiglas extension atop the outfield wall.

Outfielders weren’t crazy about the walls for a different reason: The fencing was draped in canvas, deadening any ricochet of a fly ball, while the wall’s makeup allowed it to flex back as much as three feet when players crashed into it. True, it might have helped outfielders catch a home run ball when a more hardened wall wouldn’t allow them the chance, but the stretch also led to a bit of disorientation from those who worried that the whole thing might give way.

The one signature feature of the Metrodome’s baseball configuration was the right-field wall—or tarp, or Hefty bag, or whatever people decided to call it. All choices were usually based on ridicule. Here, the first seven feet of the fencing was your traditional hard wall, but then it was topped by 23 feet of black trash-bag fabric that largely hid 7,600 tucked-away football seats. The sum total created more headaches for outfielders who didn’t know if a deep fly would bounce hard off the lower wall, or plop straight down from the baggy portion above.

The issues certainly didn’t start and stop with the outfield wall. The artificial turf had so much bounce that balls often skyrocketed over fielders’ heads, like one of those super bouncy balls kids slam down on concrete so they can watch it zoom toward the stratosphere. Then there were the fly balls and pop-ups that got lost against the white fabric roof and supporting structures that caused further distraction; on occasion, some of those obstacles (speakers, in particular) deflected pop-ups skied into the air. Infielders, especially, were often left helpless in desperate pursuit of these redirects, looking silly as they weaved and teetered about before making the catch—that is, if they were lucky to do so.

Sometimes the ball just never came down. The tall, lanky and powerful Dave Kingman, who tested the inner parameters of every enclosed stadium, once shot up a towering pop fly during a 1984 game—one that also managed to be accurate enough to find its way through one of a number of drainage holes in the roof’s lower layer. Kingman was rewarded with what the Star Tribune cutely referred to as a “roof-rule double”; the ball was eventually retrieved, autographed, and sent to the Hall of Fame.

It was a good thing that Kingman’s poke wasn’t mighty enough to bring the whole roof down. But the air-supported fabric didn’t need Kingman to cause havoc; the weather outside took care of that. Heavy snow caused one tear at the very end of 1982—and officials patched it up in time for a Vikings game in which Tony Dorsett of the opposing Dallas Cowboys memorably ran off a 99.5-yard touchdown run. Another snowstorm completely collapsed the roof a week into the 1983 baseball season, leading to one of only two postponements of a Twins game at the Metrodome. (The other came in 2007 after the deadly collapse of the nearby I-35W bridge over the Mississippi River.)

Perhaps the scariest moment in the stadium’s early years took place during a game in April 1986 when a vicious thunderstorm caused the roof to undulate wildly, like angry sea waves in the middle of the ocean. The field was cleared for nearly 10 minutes as officials, players and fans alike kept a wary eye on the roof in hopes that it wouldn’t come crashing down upon them. Thankfully, it didn’t. Although the roof held that night, an exasperated MSFC was so set off by the frequent other tears that it sued the stadium contractors (including the architect, Skidmore Owings and Merrill) and won a $3.6 million judgment in 1990.

A Rather Rough Honeymoon.

In the Metrodome’s infant years, there was a problem almost as big as the roof’s questionable integrity, aesthetic eyesores and thoroughly unnatural baseball conditions: The Twins themselves. Loaded with as many as 15 rookies for their first year in the Metrodome, the 1982 Twins were simply horrible—they won just 14 of their first 64 games and eventually lost 102, the most defeats they would suffer in Minnesota until 2016. And that new ballpark bump at the gate? Didn’t happen. The Twins finished last in AL attendance with 921,186 tickets sold.

This presented a problem. A curious stipulation had been written into the Twins’ initial 30-year lease at the Metrodome saying that if the team failed to average 1.4 million over any three consecutive years, it could break free of the lease. The Twins’ dubious draw of 1982 was followed by an even lesser gate of 858,000 in 1983—despite air conditioning being planted midway through the season and an improved (but still fairly bad) Twins team. The pivotal third year, representing 2.4 million or bust for the Twins and owner Calvin Griffith, got off to a demoralizing start at the turnstiles even as the team began to show promise of contending. Griffith, who had already moved the franchise once, was eyeing news out of the Tampa-St. Petersburg area in Florida—where officials had just given approval to build a domed ballpark for any major league team willing to make the move there.

Thus began the “Great Ticket Buyout.” Local business leaders came together and, in an effort to save the Twins from leaving, bought up tickets in bulk. Few of them were used; one game in May “drew” a paid crowd of 51,863, though only 6,000 were actually there. Griffith wasn’t thrilled with the mass ticket scheme, but he began to listen when some of those buying also inquired about purchasing the team; by the end of the year, Carl Pohlad, a local holding company magnate, bought the Twins and ensured their long-term survival in both Minneapolis and the Metrodome.

The 1984 season became as much a turning point for the franchise on the field as well as off it. Many of the young cadets who endured the Metrodome’s baptism by fire in 1982 were emerging into bona fide stars, a list that included slugger Kent Hrbek, solid third baseman Gary Gaetti and southpaw ace Frank Viola. Joining them in 1984 was a center fielder of curious short and stocky build who would come to be known as the most popular Twin of his time.

Kirby Puckett lashed out four hits in his major league debut at the Metrodome, and he hardly stopped there; not only did he tame the beast that was the stadium’s challenging intricacies, he corralled them to his advantage. He dashed and darted on the basepaths as he laced and blooped hits that played Keep Away from opposing outfielders, expanded the canvas fencing in center to steal one home run after another, and gradually powered up at the plate—going from no homers in his rookie campaign to 31 just two years later. In Metrodome annals, Puckett would be one of two players with six hits in a game, the only one with four doubles, and one of six to drive in seven runs; in fact, he did it twice. Not surprisingly, Puckett holds the #1 spot on a majority of offensive categories within the stadium’s career batting charts.

Puckett would become so beloved in the Twin Cities that, after severe eye issues forced him to retire in 1996, the street passing in front of the Metrodome’s main entrance would be renamed Kirby Puckett Way—something that would take on a sour tone when revelations came to light of Puckett’s post-career dark side, which included spousal abuse, mistress abuse, and a ballooning frame (300 pounds plus) that likely contributed to his death at the young age of 46 in 2006.

Behind home plate was a series of vents from which air flowed to keep the roof inflated; a Metrodome field superintendent later admitted that he cranked up the air to create a “blowing out” effect when the Twins were in need of runs late in a game. Later tests to confirm the scheme’s effectiveness proved inconclusive. (Associated Press)

Wind Aided?

The Metrodome was never more alive than in 1987, when the Twins put together one of the more exciting—to say nothing of curious—championship campaigns in major league history. One look at the Twins on paper showed a team that hardly looked the part of a champion; their team earned run average was a substandard 4.63 (which ranked 10th out of 14 AL teams), and they only slipped into the postseason thanks to six thoroughly weak AL West opponents. But the statistical splits told a more intriguing story; though awful on the road at 29-52, the Twins were all but invincible at home, posting a 56-25 record that would mark their best-ever regular season performance at the Metrodome. They’d be even better under the Teflon in October, upsetting the highly-favored Detroit Tigers (98 wins) in the AL Championship Series and St. Louis Cardinals (95 wins) in the World Series, winning all six of their games at the Metrodome (while winning two of six on the road). The multiple personalities displayed by the Twins were unparalleled in baseball history; somewhere, even Sybil must have been sitting on the patient’s chair and thinking, “What’s with these guys?”

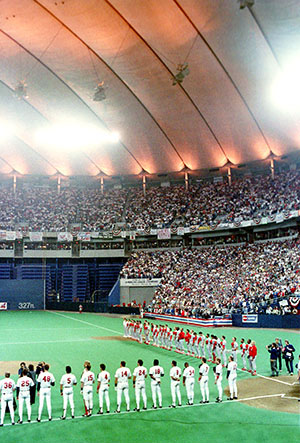

The Twins’ unlikely path to the top in 1987 could be summed up from a number of different angles. The offense was potent, with three guys (Hrbek, Gaetti and Tom Brunansky) each hitting over 30 homers; Puckett, with 28, nearly made it a quartet. An energetic fan base gave the Twins as great a 10th-Man advantage as could be found anywhere, loading up the Metrodome, waving white hankies with blizzard-like omnipresence and wearing out their vocal chords with such high resonance that decibel readings compared it to a 747 on take-off. The acoustics were so ear-shattering, pitching coaches in the dugout took the bullpen phone off the wall and placed their feet on top of it so they could feel it ring; there was no chance they were going to hear it.

Then there was the wind. As the Twins piled up the wins at the Metrodome throughout 1987, opponents became suspicious that stadium officials were pumping air through four large, circular vents behind home plate late in close games—but only when the Twins were at bat and in need of offense. The idea, of course, was that this would create a wind that blow out to the fences. Texas Rangers manager Bobby Valentine went so far as to place streamers (in the form of tape) from one of the vents to see if and when it would blow outward. But when Valentine wasn’t looking, Twins personnel tip-toed over and removed them.

Sixteen years later, the Anemoi of the Metrodome revealed himself. Dick Ericson, who retired in 1995 after serving decades as the Twins’ superintendent at both the Metrodome and Metropolitan Stadium before it, admitted that he indeed had blasted air through the air ducts behind home plate when the Twins were in need of a push. While stadium officials dismissed Ericson’s claims as a “bunch of hooey” and the Twins pled ignorance, at least one co-worker said he saw, first-hand, Ericson personally at the controls, turning on the fans.

With the conspiracy theory proven to be true, the next question became: Did the manufactured wind actually make a difference in pushing fly balls further away from home plate? To determine the answer, a professor of fluid dynamics at the University of Minnesota gave it the ol’ college try, offering a special class to students on the effects of fly balls within the Metrodome. Tests revealed vague results—basically, the conclusion came back that maybe a baseball could go as much as four feet further, but it depended on the atmospherics of the moment.

The Sports Mall of America.

The Metrodome, moments before Game One of the 1987 World Series won by the Twins. The roar of 50,000 deafening fans within an enclosed space created a decimal level equal to that of a 747 at take-off. (Associated Press)

Later that spring, college basketball’s Men’s Final Four tournament was played at the venue, with the playing floor nestled up against the permanent seats over the baseball infield while temporary stands were pitched up elsewhere; it was a big enough hit that the NCAA returned in 2001. On the pro hoops side, the National Basketball Association made the Metrodome home for the expansion Minnesota Timberwolves in 1989, shattering the league’s all-time attendance mark with an average of 26,160 spectators per game—a record that still stands—before moving into a new, more traditional basketball arena (Target Center) for the following season. The impressive gate, which included 49,551 for the team’s final game of the season—with people sitting seemingly miles away in the farthest reaches of the upper deck—was all the more impressive considering that the Timberwolves finished 22-60.

Throughout this high period, there were also the Twins—who continued to thrive on the Metrodome’s various home advantages, dubious or otherwise. On the heels of their 1987 World Series triumph, the Twins in 1988 became the first AL team to draw three million fans—well, sort of. To ensure the passing of the milestone, a local radio station perpetrated a second “Great Ticket Buyout” and purchased 50,000 seats for a late-season series against the White Sox. Very few of them were used, but it helped to inflate the actual crowd to a more official, but less truthful, count of over 40,000 for each game. The bump proved fruitful for the Twins’ ego, as they passed the three-million barrier at season’s end by 30,000.

Still, the Twins were wildly popular at this time—and after being thumped down to a last-place (albeit not-so-awful) 74-88 record in 1990, they rebounded back to prominence a year later and enjoyed the franchise’s finest hour that October.

For a brilliantly robust and entertaining seven-game World Series between the Twins and Atlanta Braves, the home advantages came back to life. There were the white hankies. There was the ear-shattering din. There was the shady gamesmanship—besides Ericson’s strategic use of air flow, there was Twins first baseman Kent Hrbek literally lifting the Braves’ Ron Gant off base, tagging him out, and somehow getting away with it.

But there was also Kirby Puckett and Jack Morris. Down three games to two as 1991 mirrored that of 1987—Twins winning at home, Twins losing on the road—the series came back to Minnesota for a sixth and, if necessary, seventh game. Puckett helped make Game Seven reality; his leaping catch high above the left-center field wall off, yes, poor Ron Gant, again, took two runs away from the Braves early on and helped bring about extra innings—which he ended with a leadoff homer in the 11th to win Game Six, 4-3. The next day, it was Morris, the 36-year-old Minnesota native and one-year Twins wonder (after a long, profitable tenure in Detroit) who pitched the game of his life—a 10-inning, seven-hit shutout won by the Twins, 1-0, when Gene Larkin’s deep fly sailed over a drawn-in Atlanta outfield to bring home Dan Gladden and give the Twins their second world title over five seasons.

From First to Worst.

The Twins’ 1991 world title was the culmination of baseball’s unprecedented worst-to-first campaign, but the Metrodome didn’t necessarily follow suit. As popular a destination for elite sporting events as it had become, the stadium couldn’t mask away all the criticism that still poured in from those who came to watch, write and perform there. At the same time, a flurry of new stadiums and ballparks had begun to spring up that would be more sophisticated, aesthetically driven and fan-friendly. The opening of Oriole Park at Camden Yards in 1992, in particular, unleashed the highly popular retro ballpark movement—leaving “modern” multi-purpose venues such as the Metrodome suddenly looking tired, passé and open to even more ridicule.

Carl Pohlad, who had saved the Twins from leaving Minnesota back in 1984, now began to understand how Calvin Griffith before him had felt. Throughout the 1990s, stuck at the Spartan, municipal Metrodome, Pohlad watched helplessly as one beautiful ballpark after another opened its doors elsewhere, with all the economic perks and feel-good publicity attached. As those teams gorged on the abundant revenue and vibe that those new yards provided, Pohlad felt more and more left behind, choking on the dust. The stars of the Twins’ championship years faded or leaped to bigger riches via free agency, and the replacements who followed lacked both panache and talent as the Twins in 1993 began a run of eight straight losing seasons. Adding to Pohlad’s misery was the 1994-95 work stoppage that turned baseball fans off everywhere through the remainder of the decade.

The Twins, by now synonymous with “small market” as loudly preached by critics of baseball’s revenue balance (or lack thereof), were annually written off as a team that conceded the season on Opening Day. Twin Cities fans bought into the story and stopped coming; it all bottomed out in 2000 when the Twins, just 12 years removed from their gate of three million at the Metrodome, surpassed one million—in their final home game, by a mere 760 fans. If there was another Great Ticket Buyout to help eclipse the mark, the buyers were probably too embarrassed to publicly admit it.

Pohlad, by now, was on the warpath to get local and/or state politicians to spring for a new ballpark. The slam-your-fists-on-the-city-council-podium tactic that worked for major league owners in so many other cities was going to be a much tougher trick in Minnesota, where austerity, progressivism and, on occasion, a little bit of chutzpah ruled—just ask the voters who gave actor/wrestler Jesse Ventura the Governor’s chair in 1999. Pohlad tried again and again to start and jumpstart negotiations for a new ballpark, with no luck.

From a distance, it looks like real grass, but it’s not; in response to the yearning of baseball fans to experience a less synthetic time and place, the Metrodome in 2003 installed a new coat of artificial turf with patterns to give it the look of freshly-mowed real grass. (Flickr—Jesse Thorstad)

The Attempted Twin Killing.

With the St. Petersburg card used up because the Florida city now had a tenant in the expansion Devil Rays, Major League Baseball had a more novel solution to the dilemma of Pohlad and the Twins: Rather than threaten to move the team, just shut it down. And that’s exactly what 28 of 30 major league owners decided to do toward the end of 2001 when they voted to reduce MLB by two teams, eliminating the Twins and Montreal Expos. In effect, the Metrodome, which had been built to save baseball in Minnesota, was now about to take the blame for killing it.

Commissioner Bud Selig was blunt when explaining baseball’s decision to fold the Twins, telling the Star Tribune: “…At some point in the past decade, despite 26 or so stadium proposals, there were chances to do something, and nothing got done. So there are a lot of people (in Minnesota) who have to look themselves in the mirror.” Pohlad was on board with contraction, happy to take a $250 million buyout from the other owners; his son Jim wrote to stunned team employees: “Within the context of baseball’s commitment, when we are posed the question, ‘Why should the Minnesota Twins not be contracted?’ we are unable to find a plausible answer.”

It was clear that the elimination of the Twins had nothing to do with “markets that generate insufficient local revenues to justify the investment in the franchise,” as Selig so wirily put it. It was, in fact, nothing more than a power play to light a match under Minnesota authorities to get moving on building the Twins a new ballpark. State politicians didn’t respond to the threat, but state judges did: They ordered the Twins to adhere to the existing Metrodome lease and continue to play on, or else. Selig and Company, legally rebuffed, had no choice but to pull the plug on contraction, rather than on the Twins.

And then a funny thing happened. Rather than feel depressed and unwanted in the wake of contraction, the Twins responded to the whole messy saga by winning again. Ron Gardenhire, taking over the reins of from long-time Twins skipper Tom Kelly, hoisted Minnesota to a first-place finish in the AL Central—its first of six such titles over the next nine years, as fresh blood was infused into the roster with impressive results. In came Joe Mauer, a hitting machine of a catcher who earned six All-Star appearances; ace/strikeout master Johan Santana, a two-time Cy Young Award winner in a Twins uniform; and closer Joe Nathan, stolen from the San Francisco Giants and savior of a Twins-record 260 games.

The Twins’ newfound divisional dominance during their last decade at the Metrodome pumped as much enthusiasm as air into the venue, even as the team eagerly continued to find a new ballpark solution. Attendance gradually grew back over the respected two-million mark as the Twins did what they could to spruce up the Metrodome and make it more intimate and natural. Updated scoreboards were installed; a giant off-white curtain was draped over several thousand upper-deck seats in right-center field and served as a wall of fame of sorts, with championship banners and images of past Twins stars in a baseball card format; and, most curiously, a new artificial turf was laid down and included checkboard patterns—as if it had actually been mowed like real grass. It wasn’t outdoors, but the Twins were trying hard to replicate the feeling. As Captain Willard said of Colonel Kilgore’s troops in Apocalypse Now: “The more they tried to make it just like home, the more they made everybody miss it.”

In 2005, the Twins’ lame duck era at the Metrodome officially began after the team and Minneapolis-based Hennepin County finally agreed on a financial pact to build a new outdoor ballpark. The winning continued, but any chance of the Twins bidding adieu to the Metrodome with a third world title failed because, ironically enough, they couldn’t win a postseason game at home. From 2003-09, the Metrodome hosted seven playoff games—and lost them all. Maybe they needed to call Dick Ericson out of retirement and give the air that added push.

The Twins’ final campaign at the Metrodome, in 2009, yielded three home finales. One was the last originally scheduled regular season home game, a 13-4 victory over the Kansas City Royals on October 4—but in winning, it set up a tie-breaking 163rd game against Detroit to determine the AL Central divisional champion. That game yielded seldom a dull moment, as the Twins emerged victorious, 6-5, in a seesaw 12-inning affair on Alexi Casilla’s RBI single. The third, and this time absolute last denouement, occurred in Game Three of the AL Divisional Series to follow as Carl Pavano was outdueled by the Yankees’ Andy Pettitte in a 4-1 Twins loss, knocking Minnesota out of the postseason and out of the Metrodome for good.

A giant beige curtain was draped downward from the ceiling late in the Twins’ tenure at the Metrodome, reducing unwanted seating while adding historical panache. (Flickr—SK Motsinger)

That Ol’ Deflating Feeling.

After all of the early structural issues with the air-supported roof, the Metrodome held firm with little trouble for the latter stages of the Twins’ tenure there. The Vikings, forced to stick around another four years at the venue as they struggled to find a new place of their own, weren’t as lucky.

Birdair Structures, the original roof contractor, warned Metrodome officials in early 2010 that the roof had outlived its originally intended lifespan and needed upwards of $15 million in updates. Nothing was done.

Eight months later, on the eve of the Vikings’ penultimate home game of the season, a massive winter storm hit Minneapolis with blistering winds and 17 inches of snowfall. Fox, set to televise the game, left a camera on inside the stadium for the night, just in case something happened. Sure enough, something did; the roof, unable to hold the weight of winter, tore open—sending copious amounts of snow cascading onto the field below. The game against the New York Giants was moved to Detroit; the last home game, a week later, was moved to the University of Minnesota’s TCF Bank Stadium.

In February 2014, the roof came down again—this time, intentionally. The Metrodome was deconstructed, piece by piece, to make way for the Vikings’ glitzy new venue, U.S. Bank Stadium, which opened in 2016. The final Metrodome event took place on December 29, 2013, when the Vikings edged the Detroit Lions, 14-13.

Although the Twins had left four years earlier, baseball continued to be played at the Metrodome after their departure, serving as the home for the University of Minnesota baseball team. Its last game was played on March 27, 2013 with a 5-1 victory over South Dakota State. A crowd of 373 showed up; Reid Clary connected on the Metrodome’s last hit, a ninth-inning triple for the losing side.

Some 3,000 of the Metrodome’s bright blue seats were torn out and sold at prices as high as $80 a seat. Eight hundred of them showed up 117 miles to the south of Minneapolis in Wells, where a high school installed them in their football stadium. The Hefty bag wall that towered above right field was cut into two and auctioned off for a combined total of $3,000. And someone felt it was worth $375 to purchase a urinal from a Metrodome restroom, because when you gotta go, you gotta bid high.

For all the mockery it absorbed, for all the ups and downs it put the Twins through, the Metrodome should nevertheless be praised for many things. It gave the Twins nearly 200 more wins than losses. It brought in not only the Vikings from the bitter cold, but also wintertime joggers who were allowed to run laps within its concourse. It was a magnet for major events; it remains the only sports venue to host the World Series, MLB All-Star Game, Super Bowl and NCAA Final Four. It witnessed great moments; three Hall of Famers (Dave Winfield, Eddie Murray and Cal Ripken Jr.) each stroked their 3,000th hit there, while on the football field it laid claim to Tony Dorsett’s 99.5-yard run, a 99-yard touchdown pass from Gus Frerotte, and the only two 109-yard returns in NFL history. Most importantly, the Metrodome financially ran in the black through to its last day standing—proving that beauty, for stadiums as much as people, is only skin deep.

The Ballparks: Target Field With Target Field, the Minnesota Twins dared to return to the outdoors, bookending beautiful summer dates with early- and late-season fates mixing cold, wind and possibly snow. But it’s all worth it at a ballpark that’s hard not to love, an inviting and modern ode to land and city that welcomes its fans with open arms and entertains them with courteous charm.

The Ballparks: Target Field With Target Field, the Minnesota Twins dared to return to the outdoors, bookending beautiful summer dates with early- and late-season fates mixing cold, wind and possibly snow. But it’s all worth it at a ballpark that’s hard not to love, an inviting and modern ode to land and city that welcomes its fans with open arms and entertains them with courteous charm.

The Ballparks: Griffith Stadium Your ballpark has burnt to the ground and you’ve got three weeks before Opening Day. Quick—whaddyado? Ask the Washington Senators, who performed the ultimate rush job and constructed Griffith Stadium as one of the more architecturally coarse and confusing of venues, with a playing field so distant and awry, the whole outfield became Triples’ Alley. Fans and presidents were nonetheless thrilled by the breathless action between the lines.

The Ballparks: Griffith Stadium Your ballpark has burnt to the ground and you’ve got three weeks before Opening Day. Quick—whaddyado? Ask the Washington Senators, who performed the ultimate rush job and constructed Griffith Stadium as one of the more architecturally coarse and confusing of venues, with a playing field so distant and awry, the whole outfield became Triples’ Alley. Fans and presidents were nonetheless thrilled by the breathless action between the lines.

Minnesota Twins Team History A decade-by-decade history of the Twins, the ballparks they’ve played in, and the four people who are on the franchise’s Mount Rushmore.