THE YEARLY READER

1907: Cultivation of a Georgia Peach

Angrier than life, Ty Cobb comes of age and delivers the Detroit Tigers to their first American League pennant.

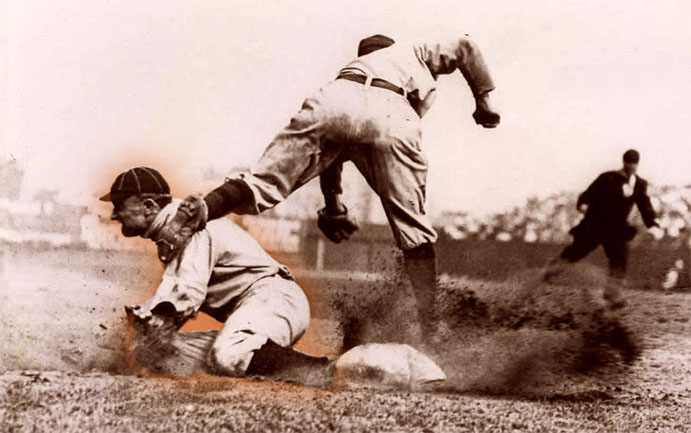

As this famous photo illustrates, Ty Cobb was a Molotov cocktail of emotions: Inflammable, explosive and defiant, with any opposing fielders who got in his way expendable. He was, at age 20, also greatly talented enough to bring the Detroit Tigers to the World Series. (Library of Congress)

When Tyrus Raymond Cobb, age 18, arrived on the major league baseball scene in 1905, his life was in total disarray.

The Georgia-bred Cobb had never traveled outside of the Deep South, and he’d never set foot in a big city like Detroit, where he had been summoned to play for the Tigers. Once in the Motor City, alone, Cobb took the first room he could find. He thought it was a hotel. Slowly did he realize it was a brothel.

Overshadowing all of the above for Cobb was the traumatic incident of a week earlier. Cobb’s father—an overbearing figure of tough love, a former Georgia state senator, a man young Ty had bent backwards over to prove he could play big-time baseball—was shot to death quietly trying to enter his house in the wee hours of the morning.

The killer: Cobb’s mother.

Yet the young Cobb went ahead with his dream of playing in the majors, channeling both his angst and anger with an already aggressive attitude that would never seem to abate—and perhaps even intensify with age, according to those who saw Cobb’s personality as increasingly “psychotic.”

One thing about Cobb was certain: He was a true, one-of-a-kind baseball talent.

As 1907 approached, the Detroit Tigers were known as one of the American League’s weaker links. The team had registered just one winning season over its first six campaigns, attendance was low, and AL czar Ban Johnson occasionally toyed with the idea of moving the franchise elsewhere.

Arriving to help put the team back together was new manager Hughie Jennings, a veteran of the fabled 1890s Baltimore Orioles. Like old Orioles teammate John McGraw, Jennings was a magnetic presence on the field—but his character was more jovial in contrast to McGraw’s icy disposition. A half-blooded Indian with a career .311 batting average, Jennings was almost as famous for his affable war chants to inspire his players.

Inspiration was one thing; cohesiveness was another. Jennings discovered from the first moment he stepped into the Tigers clubhouse that this was a team with a shattered morale. And Ty Cobb was at the heart of it.

By this time, Cobb had logged a year and a half with the Tigers. It had been quite an experience. Veteran players historically made instant targets of youthful newcomers, yet they left Cobb to himself in 1905, sensitive to his family situation. A year later, however, they let him have it. They broke his bats, nailed his cleats to the floor, stashed rotten fruit in his pockets. They kidded him on his Southern upbringing. The 19-year old’s abrasive way of reacting only made things worse for him.

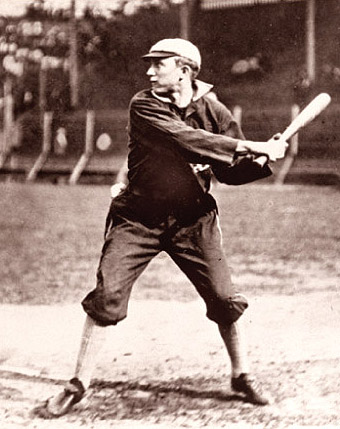

Ty Cobb as an 18-year-old rookie with Detroit in 1905. His first two years with the Tigers were marked by constant, torturous relations with his teammates. (The Rucker Archive)

On the field, after an unimpressive .240 rookie showing, Cobb came bursting out in 1906. But after hitting near .350 at the halfway point, Cobb began to feel the physical side-effects from the pressures of the past year. Eventually he was diagnosed with an ulcer, brought on by a nervous breakdown he’d suffered early in the year. Cobb enlisted into a sanitarium where he recovered for six weeks, then returned to the Tigers where he ended up hitting .319 for the year—the sixth best batting average in the AL. No one else on the Detroit roster reached .300.

But Cobb’s relationship with his Tigers teammates had not warmed. He engaged in a vicious fight with pitcher Ed Siever in the lobby of a St. Louis hotel; to his teammates’ surprise, Cobb rendered the 30-year-old veteran’s face a complete mess. Fearful of retaliation, Cobb concealed a loaded gun on board the train out of St. Louis to protect himself from the rest of the team.

Spring training 1907, even with Jennings now in command, was not without trouble for Cobb. After discovering that someone had torn up his glove, Cobb didn’t go after his teammates but, instead, a groundskeeper and his wife—both of whom were black. After starting a punishing attack upon them, he was restrained by teammates—including catcher Boss Schmidt, a boxer on the side who decided to administer some sparring on Cobb himself. It was not the only time Cobb and Schmidt would duke it out at camp.

For Tigers management, these incidents nearly became the last straw for Cobb’s stay in Detroit. They offered Cobb to Cleveland, straight up, for 31-year-old Elmer Flick, a consistent .300 hitter. The Naps, unwilling to pick up Cobb’s emotional baggage, rejected the offer. Even with Cobb’s character considered, it was a non-trade that Cleveland would kick itself for in future years; Flick’s career flickered out after the 1907 season, while Cobb flourished into becoming baseball’s first 4,000-hit man.

If Detroit players weren’t happy with Cobb the man, they had to appreciate Cobb the player, especially as the 1907 campaign progressed toward summer. Now 20, the left-handed hitting outfielder was electrifying the AL by leading the league at the plate in batting average, hits and runs batted in; on the basepaths, he led the league in steals with an obsessively furious and aggressive energy that perfectly mirrored his character. His efforts had, almost alone, thrust Detroit into first place.

Cobb had a friend at the plate in fellow outfielder Sam Crawford, who batted .323—second only to Cobb’s .350 in the AL. Crawford and Davy Jones, the team’s other outfielding regular, were the only players in the league to score over 100 runs, principally due to Cobb’s presence. The rest of the batting lineup was spotty at best, further underscoring Cobb’s importance in the order.

All this, and still the rest of the Tigers didn’t come around to Cobb. He continued to be disliked; in defense of his teammates, Cobb never made many overtures to them. Worse, he made none to the press, who could have given him public encouragement.

The team’s dramatically improved hitting inspired the pitching staff. Wild Bill Donovan went from 9-15 in 1906 to 25-4 in 1907. Ed Killian came back from illness and also notched 25 wins. George Mullin, the team workhorse, finished at 20-20. A recovered Ed Siever, with or without plastic surgery to his face, came within two victories of giving the staff a quartet of 20-game winners.

With a young squad and a rookie manager, the Tigers faced the experienced Athletics down the stretch for the AL pennant. The A’s had maintained a slim lead over Detroit going into September, but pitcher Chief Bender fell to an arm injury and staff ace Rube Waddell slumped, giving manager Connie Mack big problems as the two teams met for an important three-game series at Philadelphia with a week to play.

The series ended up being a one-game affair—officially. After Detroit won the first matchup, the second game was rained out and rescheduled as part of a doubleheader with the third game. But when the initial game of the twinbill remained tied after 17 innings under darkening skies, it was stopped and the nightcap canceled with it, neither to be made up. By virtue of preserving a one-game lead, the Tigers ended up as the true victors of the annulled doubleheader.

BTW: In later years, any canceled games with a direct bearing on postseason participation would have to be made up.

The Tigers had escaped Philadelphia on a lucky note. They had, in the extra-inning affair, overcome a six-run deficit in regulation, only squaring things up when Cobb himself launched a two-run homer off Waddell in the top of the ninth inning.

After sweeping lowly Washington to run its winning streak to 10 games, Detroit earned its first-ever AL pennant. But the anomaly of numbers among the final standings was among the strangest ever seen in baseball. The A’s had lost one less game than Detroit, but by playing fewer games overall—and winning four less—they finished a game and a half back, the only time in major league history that the team with the fewest losses placed second.

Killing Opponents With Their Deadball

The Cubs’ record-breaking 1.73 ERA was hardly a blip of history for the team’s pitching staff. Over a five-year period late in the 1900s, the Cubs would produce four of the eight best team ERAs—including the three best—in major league history.

While the Tigers fought everyone—themselves included—to reach the World Series, the Chicago Cubs breezed through the National League for the second straight year. After winning 116 games in 1906, there was no reason for Frank Chance to tinker with his squad, which in 1907 won 107 more—once again providing little drama in the NL race, decided by a full 17 games over Pittsburgh.

Pitching and defense remained the Cubs’ strength. The staff earned run average of 1.73 was the lowest in major league history—and their five main starting pitchers all had ERAs under 2.00, including league leader Jack Pfiester’s 1.15. The team combined to shutout its opponents 32 times.

After a shocking World Series loss the year before to the White Sox—and hoping to show something for an astonishing two-year record of 223-81—the Cubs were primed to take their anger out on the Tigers.

Before the Series began, players for both teams were notified that they would share the gate receipts for all games. They would even be allowed to collect on any game that might be declared a tie, for instance, on account of darkness.

Game One ended up a tie, called on account of darkness.

Baseball executives wondered aloud if certain players had purposely evened the score to collect more money. Fingers were especially pointed at Detroit catcher Boss Schmidt—he of the Ty Cobb beatings—who allowed seven Chicago steals on the day, and whose passed ball on a two-out, third strike pitch in the bottom of the ninth allowed the tying Cubs run to cross home plate. The game, but not the money, was declared void after 12 innings as darkness settled in.

After Chicago took care of business and swamped the Tigers over the next three games, rumor had it the Cubs would lay down and let the Tigers win, sending the series back to Chicago for more gate receipts from bigger crowds. But even if it crossed their minds, the Cubs didn’t want to risk the possibility of losing a second straight series they were heavily favored to win. They finished off the Tigers in an official four-game sweep, Chicago’s vaunted pitching staff leading the way by allowing just three runs in its four victories.

In the end, the players almost would have been forgiven for trying to forge extra games for the sake of extra income. The World Series gate was among the weakest in history, with only 7,000 showing up for the Game Four finale at Detroit. Cubs management made it up to their players by letting them perform in a series of post-World Series exhibitions that increased their earnings, while rumor was abuzz that the Tigers—who despite a breakout campaign, drew only 297,000 on the year—were ready to shuffle off to Buffalo.

BTW: Among AL teams, only the last-place Washington Senators drew fewer fans through the turnstiles than Detroit.

Empty-Seated Finals

The first five World Series produced the five smallest crowds in the Fall Classic’s history, headlined by the final games of the 1907 and 1908 Series in Detroit. For those who think that such indifference for a major league championship was remarkable, remember this: There were 30,000 unsold seats at the first Super Bowl.

Almost as disappointing as the Tigers’ World Series attendance was the performance of Ty Cobb, who couldn’t hold up to his regular season numbers. He batted just .200—three singles, a triple, no runs batted in, and no stolen bases—against tough Cubs pitching.

Tormented by ghosts of the past and reviled by his teammates of the present, be loved or hated, Ty Cobb was in baseball to stay. The sensational young superstar was only just beginning to make his name the stuff of legends.

Forward to 1908: The Merkle Boner Angrier than life, Ty Cobb comes of age and delivers the Detroit Tigers with their first pennant.

Forward to 1908: The Merkle Boner Angrier than life, Ty Cobb comes of age and delivers the Detroit Tigers with their first pennant.

Back to 1906: The Hitless Wonders Christy Mathewson and Joe McGinnity completely deny the Philadelphia Athletics in the World Series.

Back to 1906: The Hitless Wonders Christy Mathewson and Joe McGinnity completely deny the Philadelphia Athletics in the World Series.

1907 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1907 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1907 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1907 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1900s: Birth of the Modern Age The established National League and upstart American League battle it out, then make peace to signal in a new and lasting era.

The 1900s: Birth of the Modern Age The established National League and upstart American League battle it out, then make peace to signal in a new and lasting era.