THE YEARLY READER

1920: Saviors of the Game

Backed against the wall in the wake of the Black Sox Scandal, baseball owners respond by hiring an authoritative first “commissioner”—Kenesaw Mountain Landis—to restore the game’s credibility; they also stumble upon an explosively popular new hero in Babe Ruth.

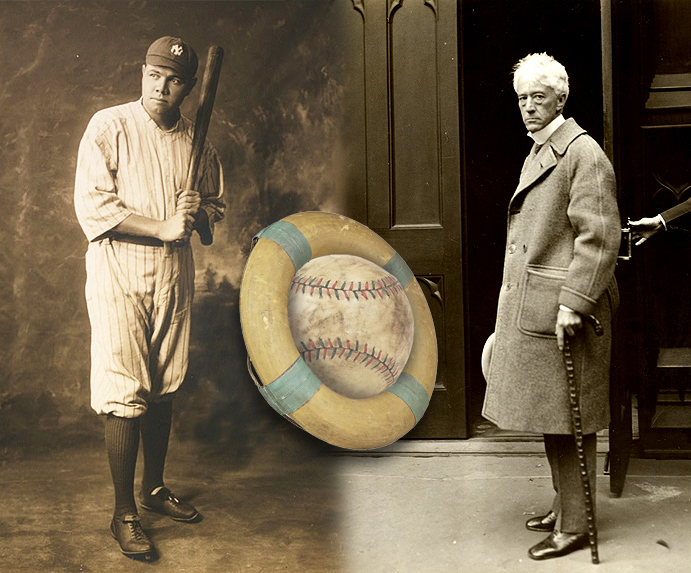

Babe Ruth (left) and first commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis forever changed the face of baseball starting in 1920, rescuing the sport in the ugly aftermath of the Black Sox Scandal. (The Rucker Archive; Library of Congress)

George Herman Ruth and Kenesaw Mountain Landis will never be accused of being separated at birth. There was Ruth, the big, fun-loving troublemaker who lived life to the fullest—and then some. And there was Landis, the frail-looking, crusty disciplinarian of a judge.

Yet they did have their similarities.

Both had flamboyant, if not self-serving, personalities, never afraid to flaunt their traits. They had both made earlier contributions to baseball in ways few people realize: Ruth as a star pitcher for the Boston Red Sox, Landis as a judge whose 1915 ruling on the Federal League helped lay the roots for the game’s antitrust exemption.

And it would be these two men who, starting in 1920, would essentially define the game of baseball for generations to come.

Ruth had already become the center of attention throughout the sporting world well before the new season approached; the New York Yankees bought him from the Boston Red Sox for $125,000—doubling the previous record purchase price for a ballplayer. That wasn’t all; the Yankees gave cash-strapped Red Sox owner Harry Frazee a $350,000 loan with Fenway Park as collateral. Though the so-called “Rape of the Red Sox” by the Yankees was far from over, it had just suffered its most serious molestation.

Landis’ name had first come to the forefront thanks to another Red Sock-turned-Yankee: Pitcher Carl Mays. Intensely surly yet very proficient, Mays stormed off the field during a game in 1919, vowing never to pitch again for a Red Sox team he felt gave him no backbone. When American League President Ban Johnson nixed the effort to place Mays in Yankee pinstripes, the team sued and won. The controversy brought into the open the hatred some AL teams had for Johnson and his dictatorial powers. A series of meetings to discuss the Mays matter got so tumultuous, it nearly split the AL apart, with three teams—New York, Boston and the Chicago White Sox—threatening to join the National League.

The NL had already thought up the idea of a non-baseball man, an outsider with no direct ties to any ballclub, to be the game’s “commissioner.” Landis was on a wish list of names that included former President William Howard Taft. Ban Johnson already believed he was that man; but the AL’s founding father didn’t fit the NL’s ideal profile since he held stock in several AL clubs—which, not coincidentally, made up the minority of clubs trying to restore the power Johnson had lost as a result of the Mays controversy.

BTW: The idea is said to have originated from Cubs minority owner Albert Lasker.

And so the league went into the 1920 season with, essentially, no one with the authority to lead it.

If the powers that would be were looking for someone to take attention away from them, they found him in a big way with Babe Ruth.

Ruth’s performance in 1920 dropped jaws everywhere. Eyes widened. Double takes ensued. Here was the man of unlikely build—broad shoulders, rotund waist, skinny knees, a trot that seemed to mimic a tip-toeing tyrannosaurus rex—who with 54 massive swings of his bat knocked the deadball era into absolute oblivion.

After going powerless in the first two weeks, Ruth connected on his first home run as a Yankee on May 1—cruelly enough, against the Red Sox—and from there quickly heated up. He eclipsed his own season home run record of 29 with the season barely halfway over. Fans had perceived 30 homers as an unbreakable barrier, but Ruth blew right through it without pause. To 40. To 50. And when the season finally ran out, he was forced to stand pat at 54.

Ruth out-homered every other AL team. Individually, the St. Louis Browns’ George Sisler was second in homers—with 19. Ruth’s slugging percentage of .847 also smashed a major league record; opposing pitchers, desperately trying to find a way to disable his strength, generally conceded him a base to the tune of 148 walks, another record.

BTW: Ruth’s long-standing marks in slugging percentage and walks would ultimately be surpassed by Barry Bonds.

The Yankees were not the only AL team serving notice to the defending AL champion White Sox as a team on the rise. In Cleveland, another Red Sox expatriate, Tris Speaker, had doubled his duties to become player-manager and immediately elevated the Indians to contender status. Speaker the player was helping Speaker the manager by hitting .388, while three veteran pitchers—Jim Bagby, Stan Coveleski and Ray Caldwell—all chimed in at over 20 wins apiece, with Bagby continuing on to 31.

The case of Caldwell was an especially peculiar one. Struggling with the bottle, Caldwell was told by Speaker that he could get soused—but only on the night after he started. Caldwell complied and won 20 for the only time in his career.

The White Sox—honest or not—rolled on through the schedule as a team bent on gaining “revenge” for their 1919 World Series loss, showing great strength and balance throughout their roster.

The heat of the three-way AL race turned tragic during an Indians-Yankees game on August 16. On a hot day at the Polo Grounds, Cleveland shortstop Ray Chapman, a highly likable and gifted young shortstop batting .303, was unable to pick out a submarine pitch coming square at his head. The ball struck him near his temple with such a loud and sickening thud, the Yankee pitcher fielding the ball in front of home plate believed that Chapman had put it in play with his bat.

That pitcher was Carl Mays.

Chapman got up, staggered a few steps toward first base, then collapsed. The injury was so grisly, noted sportswriter Fred Lieb witnessed that Chapman’s left eye was “hanging from its eye socket.”

Never regaining consciousness, Chapman was rushed to a New York hospital—where he died the next morning, becoming the only on-field fatality in the history of the major leagues.

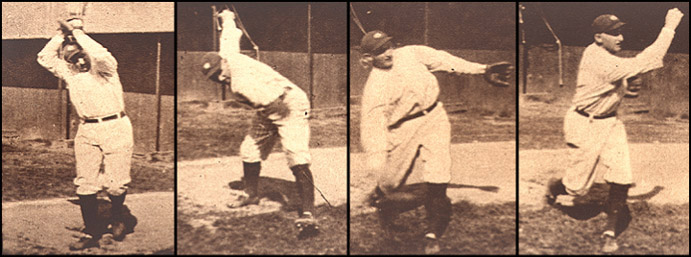

Carl Mays shows off his unique submarine-style pitching delivery. Despite a career 208-126 record, his malcontent nature and deadly (though unintentional) beaning of Ray Chapman in 1920 are likely the two prime reasons he’s not in the Hall of Fame.

On top of his irascible persona, Mays was also notorious for aggressively keeping hitters off the plate. But Chapman was also known for crowding in. Muddy Ruel, the Yankee catcher that day, insisted had the ball not hit Chapman, the pitch would have been called a strike. Mays was given the benefit of a doubt; the New York DA’s office questioned him and concluded the beaning was accidental, quickly closing the book on one of the game’s most sobering moments.

Down in Brooklyn, the Robins were charging to their second NL pennant in five years. Wilbert Robinson’s starting rotation was boosted by Burleigh Grimes, about to gain an advantage with a new rule prohibiting spitballs and other trick pitches. Seventeen hurlers around baseball would ultimately be exempted because of their reliance on the spitball; Grimes was one of them. Even though the so-called “grandfather clause” had not yet kicked in, Grimes—just an ordinary pitcher in 1919—began to throw as if he’d been given the advantage to use what the majority of others would eventually not be allowed. His 23 wins and 2.22 earned run average helped propel Brooklyn to a seven-game cushion over the New York Giants.

BTW: Though “trick pitches” were decreed illegal before the 1920 season, the National League didn’t enact the ban until 1921—while the American League allowed two pitchers per team to use such deliveries in 1920 before a total ban a year later.

The Wet Edge

When baseball announced a ban of spitballs and other trick pitches in 1920, 17 pitchers who depended on such deliveries for their livelihoods were ultimately exempted for the duration of their careers. As the chart below shows, the advantage these hurlers were given showed in the numbers they produced, even as they grew old and gray into the early 1930s.

With the NL race all but settled, the AL battle continued into September competitive as ever. Cleveland, Chicago and New York played musical chairs with first place throughout the month. Late-season acquisitions had boosted the morale of the Indians, now wearing black armbands in memory of Chapman. Future Hall of Famer Joe Sewell, 21, stepped in at Chapman’s old position and batted .329 in 22 games; southpaw Duster Mails came aboard on September 1 and proceeded to go 7-0 in eight starts to replenish Cleveland’s hopes.

With the Indians taking a slim lead into the season’s final weekend, everyone salivated for an exciting finish. Then the bomb dropped.

Billy Maharg was talking.

The man who, with Bill Burns and others, had attempted to orchestrate a fix for the 1919 World Series—and got no money for his troubles—became the first figure from within to reveal the story to the press. The news rocked America; a grand jury in Chicago, already investigating a possible fix of a Phillies-Cubs game in August, switched gears and began focusing solely on the 1919 World Series.

Some of the Black Sox players, under more pressure than ever to clear their guilty minds, broke quickly. A day after the Maharg story hit the newsstands, Eddie Cicotte and Joe Jackson confessed to the grand jury. Lefty Williams quickly followed; Happy Felsch revealed what he knew to a Chicago newspaper reporter. The ugly rumors were finally confirmed. The 1919 World Series had, indeed, been fixed.

Confessions quickly led to suspensions, and the AL race was suddenly over. All conspiring Chicago players weren’t allowed to finish the season, leaving a terribly handicapped roster at the disposal of manager Kid Gleason. The Indians coasted to the AL pennant by two games over what was left of the White Sox, and by three over the Yankees.

Never mind that the Indians went on to beat the Brooklyn Robins in the World Series. Never mind that Indians second baseman Bill Wambsganss pulled off an unassisted triple play in Game Five, or that Cleveland’s Elmer Smith hit the Series’ first-ever grand slam, or that Jim Bagby became the first pitcher to homer in a Series. The eyes of the nation were riveted instead on a courtroom in Chicago.

All eight Black Sox players and eleven others were indicted; Arnold Rothstein, the man with the money, wasn’t one of them. In a carefully orchestrated appearance before the grand jury, he played the wounded victim of innuendo and denied everything, winning over the jury’s pity with a somber facade.

The ensuing trial, lasting well into 1921, was fraught with blatant suspicion. The prosecutors during the grand jury proceedings suddenly became the players’ defense attorneys at the criminal trial. The new prosecutors couldn’t find the signed confessions of the players; they had been stolen. (It was later said that they just happened to turn up in Charles Comiskey’s possession.) Witnesses were tough to find; Rothstein had them either paid off or sent into hiding. When someone finally caught up to Abe Attell, a prosecution witness was sent to identify him—only to say he was a different Abe Attell. Rothstein’s lawyer had apparently gotten to the witness.

Despite solid testimony for the prosecution from Maharg and Burns, the jury acquitted the Black Sox players. It appeared nothing would have swayed the jury otherwise; they left the courtroom hoisting the players on their shoulders and whooped it up together that night at a Chicago restaurant.

The players had survived the trial, but the real verdict—one they didn’t see coming—was still to come.

Kenesaw Mountain Landis was approached in November 1920 when major league owners bumbled into his courtroom to formally offer him the job as baseball’s first commissioner. Landis accepted—but only on the condition that he be paid double the $25,000 a year the owners tendered, and that he be given total autocratic power. Humbly, for a change, the owners agreed.

Kenesaw Mountain Landis, baseball’s first commissioner, poses seated in front of 14 of the 16 major league owners shortly after his appointment. (Chicago Historical Society)

Joe Jackson, a .356 lifetime average third only to Ty Cobb and Rogers Hornsby—banned. Eddie Cicotte, winner of 90 games over his last four years—banned. Lefty Williams, a solid young pitcher with the promise of greatness—banned. Happy Felsch, a superior outfielder, also maturing—banned. Buck Weaver, who argued bitterly to his dying days that he did nothing to alter the World Series, despite his “guilty” knowledge of events—banned. Chick Gandil, Swede Risberg and Fred McMullin, all banned.

BTW: Gandil had “retired” from the majors and moved to California before 1920.).

By laying down the law, Commissioner Landis restored confidence and respect to a sport that had veered toward the edge of credibility freefall. The judge set the game—along with its squabbling batch of team owners—straight.

Landis had provided baseball with a much-needed leap away from its troubled past.

Babe Ruth would take it from there.

Forward to 1921: See You at the Polo Grounds The home for both the New York Yankees and Giants becomes the exclusive host to the first Subway Series.

Forward to 1921: See You at the Polo Grounds The home for both the New York Yankees and Giants becomes the exclusive host to the first Subway Series.

Back to 1919: Say it Ain’t So Eight members of the Chicago White Sox plot the unthinkable and throw the World Series against Cincinnati.

Back to 1919: Say it Ain’t So Eight members of the Chicago White Sox plot the unthinkable and throw the World Series against Cincinnati.

1920 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1920 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1920 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1920 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1920s: …And Along Came Babe Baseball becomes the rage thanks to increased offense and the magical presence of Babe Ruth, whose home runs exert a major influence upon the game for ages to come.

The 1920s: …And Along Came Babe Baseball becomes the rage thanks to increased offense and the magical presence of Babe Ruth, whose home runs exert a major influence upon the game for ages to come.