THE YEARLY READER

The 1940s: Of Rations and Spoils

Feast and famine were never more defined within baseball than in the 1940s.

After a few glorious years to start the decade, the major leagues had to play it lean, leaner and leanest through 1945 as America diverted all of its resources to winning World War II. The majority of major leaguers became absent from the game, enlisted or drafted into the armed forces to aid in the war effort. In their place, ballplayers who under normal circumstances might had been laughed out of spring training—low-level minor leaguers, semi-pros and even a few men hampered by physical handicaps—joined the scarce supply of veterans technically unfit for service and provided the nation with a brand of baseball far removed from the glamour days that began the decade, though the fans that took their mind off war to watch them understood.

World War II stripped many of the game’s greats of up to four years of their prime in baseball. If not for armed conflict, Ted Williams—arguably the best pure hitter the game has ever seen—might have finished his career with 3,200 hits and 650 home runs. Warren Spahn, the game’s most productive southpaw, quite possibly would have topped 400 wins. Bob Feller, armed with a supersonic fastball, could have won 300 games and struck out 3,500. Hank Greenberg might have joined the 500-home run club, while Washington’s Mickey Vernon could have made it to 3,000 hits. But from the heart and to a man, every ballplayer would have considered such a relatively trivial loss of statistics as a small sacrifice compared to helping America defeat the Axis powers.

When peace returned and the stars suited back up for baseball in 1946, the game enjoyed a fertile period lasting the rest of the decade that may have made for the most satisfying time of its long existence.

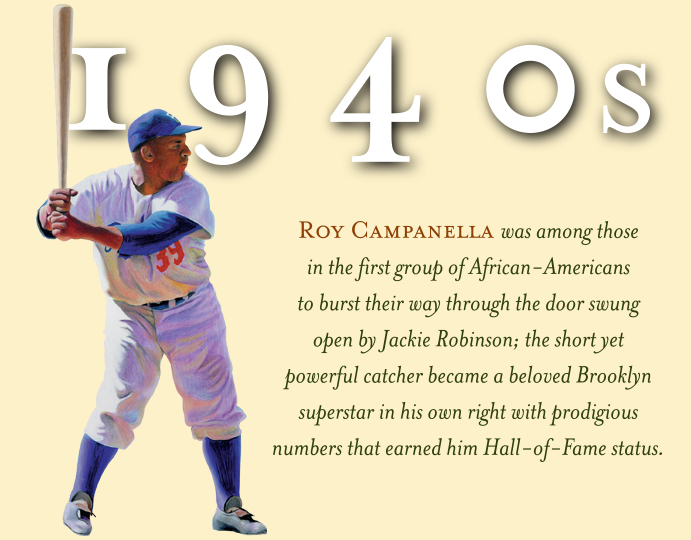

Attendance boomed as the game basked in a highly popular postwar glow, but the watershed moment during this pocket of time came in 1947 with baseball’s monumental breaking of the color barrier, as the Brooklyn Dodgers brought on Jackie Robinson to become the majors’ first black ballplayer since the 1880s. Having to endure the painful litmus test of peacefully overcoming the racism so long inherent within the majors, Robinson didn’t evolve into an American sports hero, but a heroic American—thriving as well as surviving on the playing field, and opening the door for a slow but sure stream of fellow African-Americans who would filter into the majors late in the 1940s, including Larry Doby, Satchel Paige, Roy Campanella and Don Newcombe.

The spoils of victory and the foresight of integration fueled the majors’ resurgence, making the sport as popular as ever. Now it was up to the lords of baseball to maintain and grow within the ever-changing vision of postwar America’s new frontier.

Forward to the 1950s: A Monopoly of Success Though described as a golden age for baseball, most major league teams find themselves struggling—unless you’re in New York City, where the Yankees, Dodgers and Giants hog the World Series podium from 1950-56. But as the decade winds to a close, the euphoria of Big Apple baseball will rot overnight.

Forward to the 1950s: A Monopoly of Success Though described as a golden age for baseball, most major league teams find themselves struggling—unless you’re in New York City, where the Yankees, Dodgers and Giants hog the World Series podium from 1950-56. But as the decade winds to a close, the euphoria of Big Apple baseball will rot overnight.

Back to the 1930s: Dog Days of the Depression The majors take a hit from the Great Depression as both attendance and bravado are on the wane—until newborn icons Joe DiMaggio and Ted Williams emerge to rejuvenate the game’s passion for the fans.

Back to the 1930s: Dog Days of the Depression The majors take a hit from the Great Depression as both attendance and bravado are on the wane—until newborn icons Joe DiMaggio and Ted Williams emerge to rejuvenate the game’s passion for the fans.

The Cincinnati Reds and Detroit Tigers, two teams coping with personal loss, dedicate themselves toward winning a World Series title.

The Cincinnati Reds and Detroit Tigers, two teams coping with personal loss, dedicate themselves toward winning a World Series title. Joe DiMaggio’s magical hitting streak, Ted Williams’ run at .400 and the rise of the Dodgers result in one of baseball’s most memorable years.

Joe DiMaggio’s magical hitting streak, Ted Williams’ run at .400 and the rise of the Dodgers result in one of baseball’s most memorable years. The St. Louis Cardinals benefit from their vast farm system to become the baseball’s first wartime champion.

The St. Louis Cardinals benefit from their vast farm system to become the baseball’s first wartime champion. World War II begins to exact a heavy impact on baseball’s ability to play on.

World War II begins to exact a heavy impact on baseball’s ability to play on. The powerhouse St. Louis Cardinals get a surprise World Series opponent in the neighboring Browns.

The powerhouse St. Louis Cardinals get a surprise World Series opponent in the neighboring Browns. As World War II comes to an end, Hank Greenberg makes the first and most celebrated return to baseball.

As World War II comes to an end, Hank Greenberg makes the first and most celebrated return to baseball. The players are back and so are the fans, as attendance booms in baseball’s first postwar campaign.

The players are back and so are the fans, as attendance booms in baseball’s first postwar campaign. Baseball’s color barrier is knocked down, but not without intense prejudicial resistance.

Baseball’s color barrier is knocked down, but not without intense prejudicial resistance. Bill Veeck, the maverick owner of the Cleveland Indians, brings ’em through the gates with memorable attractions on and off the field.

Bill Veeck, the maverick owner of the Cleveland Indians, brings ’em through the gates with memorable attractions on and off the field. The zany Casey Stengel silences the critics and embarks the New York Yankees on a long and fruitful dynasty.

The zany Casey Stengel silences the critics and embarks the New York Yankees on a long and fruitful dynasty.