THE YEARLY READER

1942: The Home Grown Champions

America’s entry into World War II saps the majors of many of their players—affecting everyone but the St. Louis Cardinals, whose inventory of players from their vast farm system helps ignite a terrific late-season sprint.

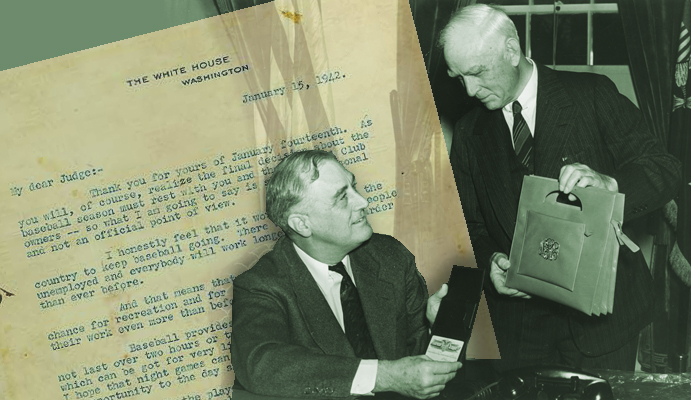

Washington Senators owner Calvin Griffith lobbied President Franklin Roosevelt to keep baseball going following America’s entry into World War II; Roosevelt’s “Green Light Letter” vindicated his efforts. (The Rucker Archive)

Twenty years had passed since Branch Rickey had concocted and perfected a vast farm system for the St. Louis Cardinals. Although other teams had since copied Rickey’s methods in producing their own talent, the Cardinals still had the strongest, most active backlog of prospects in the majors.

The Cardinals’ farm system, as always, had its advantages: You could always count on at least a few gems within the mass multitude of players corralled by the organization; if a veteran on the parent club wanted more money, Rickey would usually chuck him away and bring up someone cheaper, more eager and just as good; and of course, it always assured the Cardinals of a strong presence in the National League standings.

Rickey, however, probably never gave much thought to how a war might give his team the upper hand through his empire of prospects.

After staying officially neutral for two years, America was plunged into World War II following Japan’s blindsiding raid at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. The U.S., along with its allies, was fighting against the Axis on both sides of the Atlantic: Imperial Japan in the Pacific, Nazi Germany in Europe.

Publicly, Major League Baseball declared itself at the mercy of Washington in regards to its wartime status. But haunted by the memories of their highly criticized maneuvering to keep baseball alive during World War I, the owners brooded over the potential of draconian sacrifice—and braced for a possible, indefinite stoppage of the game.

Fortunately for the owners, they had a well-connected lobbyist in Washington: Senators owner Clark Griffith, who was in good standing with President Franklin Roosevelt. Griffith made numerous trips to the White House to mount his case for baseball’s survival, but he probably didn’t need to. Roosevelt, a big baseball fan, wrote to commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis on January 15 and personally okayed baseball’s continuation, citing that ballplayers would keep more people employed and provide escapist recreation for “at least 20 million of their fellow citizens.” FDR’s memorable “green light” decree made it certain that baseball would survive through war.

But there were no illusions that it was going to be the same.

The effects of the war slowly began to hit home at ballparks throughout the 1942 season. Spectators were asked to return foul balls to the field of play so servicemen on R&R could later use them. Radio play-by-play announcers were told not to discuss the weather on air, because it was feared the enemy might be listening in. Ominous signage was displayed at ballparks informing fans where to go in case of an air raid. And while FDR hoped for more night games, it wasn’t going to happen on the Eastern seaboard—where ballparks lining the Atlantic were barred from lighting up, since they illuminated city skylines and harbors that could make easier targets for Nazi U-boats lurking offshore.

BTW: The 1942 All-Star Game, held in New York, finished just two minutes shy of a scheduled blackout drill that would cut the lights off at the Polo Grounds.

To buffer the patriotic mood of the times, the Star-Spangled Banner was played for the first time on an everyday basis before the start of each ballgame.

America’s entry into the war also reoriented baseball history for the future. While Los Angeles braced for a possible attack from Japan, they never realized how close they came to being invaded by the St. Louis Browns—who were preparing a move to California until events at Pearl Harbor kept them back east. And in Chicago, the Cubs were ready to install lights for the 1942 season—but war re-routed those materials to more essential, military destinations. Thus, the addition of night games at Wrigley Field would be delayed for another 46 years.

For the most part, the military draft was not impacting major league rosters—yet. A number of players enlisted, most notably Cleveland ace Bob Feller, but on a whole only 50 major leaguers missed action during 1942 due to military service.

While the majors survived, the minor leagues endured more hardship—and in some cases, paralysis. There were 10 fewer minor leagues starting the 1942 campaign—and by the end of the year there would be five fewer yet, victims from a lack of able-bodied, non-drafted men to fill up their rosters.

The St. Louis Cardinals had three fewer minor league affiliates when 1942 began, but they still had double the number of any other major league team. The parent club roster bore the classic Cardinals trademark: Young, highly competitive and brought up through its own organization. There was no shortage of fresh talent, and among the youngest of the newcomers in 1942 was a baby-faced 21-year old who joined the St. Louis organization first as a pitcher—before arm troubles “relegated” him to an everyday hitter. But with one of the sweetest and most potent swings ever seen, Stan Musial was not likely to return to the mound anytime soon, batting .315 as a rookie.

BTW: With an average age of 26, the Cardinals were the youngest team in the majors.

A magnificent talent, Brooklyn’s Pete Reiser slides home as only he knows how—by sparing no ounce of exertion. Reiser’s hard-charging moxie would result in a shortened, injury-riddled career. (The Rucker Archive)

It was another prized Cardinal prospect—one that got away—who helped keep St. Louis out of first place through the first half of the season. Outfielder Pete Reiser was a shining discovery for Branch Rickey five years earlier, but when commissioner Landis—who detested major league teams’ ownership of farm clubs—declared Reiser and a large batch of Cardinals minor leaguers free agents, Rickey scrambled to make a secret deal with Brooklyn general manager and good friend Larry MacPhail: Sign Reiser, hide him within the Dodgers organization, then trade him back to the Cardinals down the line.

One problem. Neither Rickey nor MacPhail let Brooklyn manager Leo Durocher in on the secret. And when Durocher publicly ranted over a 19-year-old Reiser tearing opponents apart at the plate during the spring of 1939, an alarmed MacPhail sent a telegram ordering Durocher to shut up and bench Reiser. But it was too late; the word was out about Reiser’s exceptional skills, and the gig was up for Rickey, who was never able to reclaim his hidden treasure.

Reiser batted .378 as a minor leaguer in the Brooklyn farm system in 1939, and two years later became the youngest-ever player to win a National League batting title with a .343 mark. He was just warming up; as the Dodgers came to St. Louis eight games ahead of the Cardinals in late July, Reiser’s average stood at .383.

No one knew it at the time, but Pete Reiser’s career had just peaked.

Though immensely talented, Reiser was also foolishly aggressive on defense, chasing fly balls in the outfield with reckless abandon. And when the Cardinals’ Enos Slaughter launched a deep drive to straight-away center field during the Dodgers’ visit to St. Louis, Reiser made a mad sprint after the ball and had it in his mitt—just as he violently met face-to-face with the concrete outfield wall at Sportsman’s Park. The ball was jarred loose, but Reiser managed to pick himself up and make a throw to the infield—though it would be a full day before it was determined he had done so with a fractured skull.

Team doctors insisted that Reiser’s year was done, but MacPhail and Durocher, beginning to see the Brooklyn lead slip without him, were anxious to get him back in the lineup. Reiser, ever the competitor, was just as eager to return in spite of the pain, wanting “to win so much it hurt.”

The Dodgers felt Reiser’s pain through a gradual yet inescapable shift in the standings, as the Cardinals chiseled away at Brooklyn’s once-healthy lead. September came along, and the Dodgers finally sunk under the weight of a lineup crippled by a less-than-healthy Reiser.

It wasn’t that the Dodgers slumped in the final month; they were 16-10 in September.

The Cardinals just played better—much better. They were 21-4.

For St. Louis, the month of September was part of a larger, more impressive finish to the season in which it won 43 of its last 51 games.

The Dodgers, despite a 104-50 record that resulted in a four-game improvement over their pennant-winning performance of the year before, finished two games behind the fiery Cardinals. A healthy Pete Reiser from start to finish probably would have made a difference, but post-collision Reiser would never come close to matching pre-collision Reiser. Struggling with the painful side-effects of his injury which included double vision and blackouts, Reiser batted under .200 after hurrying back to action, finishing the year with an overall .310 mark. Reiser would enjoy a few more good years but also continued his daredevil style of play, never approaching the richness of his early years. His career collapsed into that of a bench performer by the end of the 1940s. Historians regard Pete Reiser as one of the game’s great lost talents.

After the Wall

Pete Reiser’s career was flying high until he flew head-on into the concrete wall at St. Louis’ Sportsman’s Park on July 19, fracturing his skull. Reiser would never recover from the crash and, after three years of “rest” serving in the armed forces, would return to baseball unable to recover the greatness he lost with Brooklyn, performing mostly part-time with diminished results.

Quietly repeating in the American League pennant race, the New York Yankees returned to the World Series with a roster largely untouched by draft and enlistment, save for the late-season departure of outfielder Tommy Henrich. Though their offense wasn’t as dominant as in years past—the Boston Red Sox, again finishing second, showed more life at the plate thanks to a triple crown performance by Ted Williams—the Yankees’ pitching was far superior to AL opponents, registering a 2.91 team earned run average—the lowest number seen in the AL since the end of the deadball era.

Having triumphed in their past eight visits to the World Series—winning 32 of 36 Series games in the process—the Yankees appeared well on their way to yet another Series conquest when they took Game One over St. Louis, 7-0, thanks largely to 7 2/3 innings of no-hit pitching from starter Red Ruffing.

But out of nowhere, the Cardinals ripped the momentum out from under the Yankees and stormed to four straight wins and a Series triumph. What made the turnaround all the more intriguing was the diversity of styles employed in each St. Louis triumph. In Game Two, they used the Yankee approach of making their hits count in a 4-3 thriller; they won a classic pitching duel in Game Three thanks to an unlikely performance by sore-armed Ernie White, who shut the Yankees down on six hits; proved they could win a track meet in Game Four, outdistancing New York by a 9-6 score; and, as if to add insult to injury, used the Yankees’ favorite weapon—the home run—in Game Five as Enos Slaughter and Whitey Kurowski went deep in the Cardinals’ 4-2 win to ice the Series.

It would be the last hurrah for Branch Rickey at St. Louis. The architect of one National League powerhouse would move on to uphold another in Brooklyn.

Meanwhile, the war abroad was preparing to put an even tighter grip on America and the National Pastime.

Forward to 1943: War and Games World War II begins to exact a heavy impact on baseball’s ability to play on.

Forward to 1943: War and Games World War II begins to exact a heavy impact on baseball’s ability to play on.

Back to 1941: 56, .406 and Dem Bums Joe DiMaggio’s magical hitting streak, Ted Williams’ run at .400 and the rise of the Dodgers result in one of baseball’s most memorable years.

Back to 1941: 56, .406 and Dem Bums Joe DiMaggio’s magical hitting streak, Ted Williams’ run at .400 and the rise of the Dodgers result in one of baseball’s most memorable years.

1942 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1942 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1942 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1942 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1940s: Of Rations and Spoils The return to a healthy economy and the breaking of the color barrier helps baseball reach an explosive new level of popularity—but not before enduring with America the hardship and sacrifice of World War II.

The 1940s: Of Rations and Spoils The return to a healthy economy and the breaking of the color barrier helps baseball reach an explosive new level of popularity—but not before enduring with America the hardship and sacrifice of World War II.

Mike Sandlock talks about hitting 1.000, life as a member of the Hollywood Stars and his fond recollections of Dodgers stars Roy Campanella and Gil Hodges.

Mike Sandlock talks about hitting 1.000, life as a member of the Hollywood Stars and his fond recollections of Dodgers stars Roy Campanella and Gil Hodges.