THE YEARLY READER

1971: Dynasty on the Rise

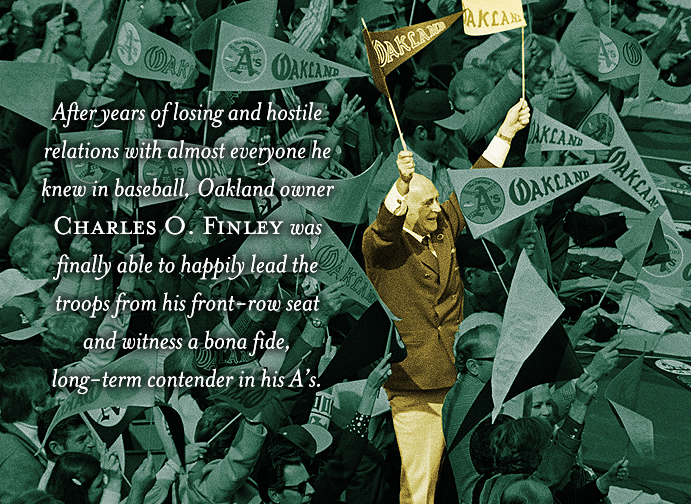

Though not yet primed for the World Series, the colorful Charles Finley is nevertheless happy to see his Oakland A’s arrive on the scene after years of poor results under his contentious ownership.

(Associated Press)

One day late in 1967, the city of Oakland, California received good news and bad news.

The good news: The city was getting a major league baseball team.

The bad news: Charles O. Finley was coming with it.

By 1971, the good news had grown increasingly better. The bundle of young, flashy Oakland A’s talent was emerging as a powerhouse in the making; it was not a matter of whether they would take over the baseball world, but when.

It was news good enough to forget about the bad in Finley, the irascible A’s owner.

Big league owners have always been a rare breed, loaded with swagger, ego and money that sometimes alienated their fans. And while the owners could at least stand one another, none of them could stomach Finley.

A tireless man who built up a multimillion-dollar insurance empire, Finley zealously pursued buying a major league team and finally succeeded when he bought the Kansas City Athletics late in 1960. With his receding gray hair, bushy eyebrows, brightly-color suits and loudly grating voice, Finley came off as the used car salesman from Hell, constantly pitching unorthodox ideas to enliven the game while the owners looked for an escape from his lot.

Finley became the majors’ most flamboyant showman since Bill Veeck. He clad the A’s in green-and-gold uniforms, painted the seats in fluorescent colors, and placed a mechanical rabbit behind home plate that would pop up and deliver new balls for the umpire. He lectured anyone willing to listen about the need for a designated hitter, orange baseballs, three-ball walks and World Series games played at night. All of this embarrassed the owners, who viewed Finley’s colorful, progressive thinking to be out-of-bounds through their purist-driven, gray-and-white prism.

The owners merely represented the tip of the iceberg among those who held nothing but contempt for Finley.

The players detested Finley, as best recalled when Ken Harrelson once angrily described him as a “menace to baseball.” His managers—nine of them in all, over a nine-year period—hated him and vice versa. Even local politicians sounded off against Finley, most memorably when Missouri U.S. Senator Stuart Symington warned California of Finley’s coming: “Oakland,” said the senator, “is the luckiest city since Hiroshima.”

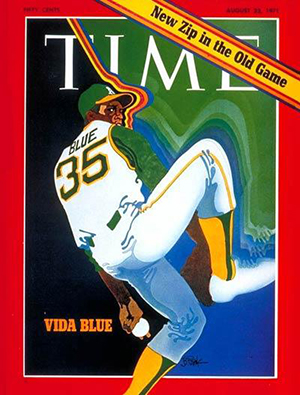

Vida Blue’s explosive breakout season merited him an illustrative appearance on the cover of Time Magazine.

Irate with the A’s lack of support, Finley threatened to move the franchise anywhere he could think of: Dallas, Louisville, Atlanta—and then Oakland, where Finley would finally make good on his vow.

Oakland would be luckier than Hiroshima—and Kansas City—in one respect: The team started to win once transplanted in the Bay Area. In 1968, the A’s enjoyed their first above-.500 finish since their Philadelphia days, and they steadily improved from there. Finley’s increasingly sharp eye for talent was beginning to pay off with a group of opinionated young players whose vibrant personalities matched the green-and gold eccentrics of their uniforms—if not Finley himself. At the top of this self-promotional list was Jackson, who burst onto the scene with 47 home runs in 1969, only to collapse a year later when a public and very bitter contract dispute with Finley affected his play.

BTW: Jackson struggled with a .237 batting average and just 23 home runs in 1970. After launching one of those at the Oakland Coliseum, he reported turned toward Finley, seated in the crowd, and barked “f**k you” at him.

Lost in K.C., Found in Oakland

In his seven years at Kansas City, it seemed A’s owner Charles Finley couldn’t find success if it was handed to him on a silver platter. But his fortunes turned almost instantly upon moving his team to Oakland in 1968.

Two major developments helped put the A’s over the top in 1971. One was the arrival of new manager Dick Williams—whose reign in Boston had met with a tumultuous end two years earlier after clashing with Carl Yastrzemski. Williams’ fiery leadership was the perfect fit for the A’s young, hungry and confident batch of players.

The other came from the sudden blossoming of 21-year-old fireballer Vida Blue, who hinted at things to come in 1970 with a no-hitter among six starts. In 1971 he came out blazing, earning a 17-3 record at the All-Star break while becoming a media sensation with cover treatments for Time and Life magazines. Finley, never one to stand in the shadows, publicly offered Blue $2,000 to be nicknamed “True” and have it sewn on the back of his jersey.

BTW: Blue wasn’t crazy about “True Blue,” and the idea ultimately fizzled.

Blue cooled through the latter part of the season as his arm began tiring of throwing fastballs, but his final record of 24-8, along with 301 strikeouts and an American League-best 1.82 earned run average, earned him both the league’s Cy Young and Most Valuable Player awards.

Elevated by Blue’s presence, Oakland’s pitching staff that was beginning to discover itself. Jim “Catfish” Hunter—he was fine with the nickname Finley gave him—was momentarily in Blue’s shadow by winning 21 games against 11 losses; it was the first of five straight years in which he’d win at least 20. Another starter, Rollie Fingers, began to mentally wig out over the role and was converted to a reliever, where he felt far more comfortable; it showed in the numbers he started putting up as the team’s closer.

Oakland pitching, powered along by the comeback slugging of Reggie Jackson (.277 average, 32 home runs, 80 runs batted in), ignited the A’s to a 101-60 record in the AL West, miles ahead of another young rising (but less talented) team in the Kansas City Royals, and an aging Minnesota squad that conceded the division after two straight first-place finishes.

Hoping to reach the World Series for the first time in generations, the A’s realized that, for now, it wasn’t going to happen against the almighty defending world champion Baltimore Orioles.

Once again laughing away the competition in the AL East, the story for the Orioles was their solid, consistent starting rotation. How solid? All four starters won at least 20 games, something previously accomplished only by the 1920 Chicago White Sox. How consistent? All four starters—Dave McNally, Jim Palmer, Mike Cuellar and Pat Dobson—all won their 20th game five days apart.

BTW: Each of the four Orioles starters lost less than 10 games; combined, they were 81-31.

Dobson was the most unlikely member of the pack. In his fifth year at the major league level, Dobson had only been a regular starter the year before with the woebegone San Diego Padres. In Baltimore, Dobson’s curveball improved—and with it his confidence, now that he was playing for a winner—and with that, the quartet of 20-game winners was complete.

The Oakland A’s got off to a good start in Game One of the ALCS behind Vida Blue, building an early 3-0 lead at Baltimore against McNally. But it would be the only light the A’s would see in the entire series, as Blue blew up in the seventh inning after retiring the first two Orioles batters, allowing four runs. The A’s would never lead in the next two games, as Cuellar and Palmer paired to wrap up Oakland with 5-1 and 5-3 scores.

In short, the Orioles’ third consecutive three-game sweep in the ALCS was the classic triumph of experience over youth.

The Oakland A’s time would come soon. Very soon.

For the Pittsburgh Pirates, the time was now. Quickly dispensed the year before by the Cincinnati Reds in the NLCS, the Bucs regrouped and played stronger baseball in 1971, easily engineering the National League’s best record at 97-65 while running away with the NL East title.

Two future Hall of Famers helped define the Pirates offensively. There was Willie Stargell, a booming, uplifting presence who definitely saw the glass as half-full—if not completely full—and led the majors with 48 home runs while knocking in 125 runs. And there was fellow outfielder Roberto Clemente, the long-time Pirate who, like fine wine, seemed to be getting better with each passing season as he aged into his late 30s. The latter-day Clemente was a marvel to behold, constantly hitting over .340 at the plate. Defensively, Clemente’s uncanny ability to launch throws from the deep outfield to the plate on a dime—and on the fly—continued to be the stuff of legends.

Yet Clemente was developing a justified chip on his shoulder over his public standing in the game, feeling unappreciated alongside superstar media darlings like Mays, Aaron, Robinson, Banks, et al. It didn’t help that Clemente harbored a quiet and introverted demeanor in a small major league berg like Pittsburgh. What he needed was a grand stage for his bat and glove, which did most of the talking anyway, to be given undivided attention.

For the NLCS, that stage would be temporarily stolen by first baseman Bob Robertson and his four home runs—three alone in Game Two—that provided the knockout punch to the San Francisco Giants, whose veteran leadership willed first place out of the NL West despite finishing seventh in the NL in batting, sixth in ERA and dead last in defense.

BTW: In defeat, the Giants did become the first team not to be swept in a league championship series since the format began in 1969.

Like Fine Wine

Roberto Clemente proved that life in the majors after 35 was anything but a big downward career spiral, raising his level of play to new heights as shown below.

As good as the Pirates had become, they took on the role of underdog in the World Series against the Orioles—and, for the first two games, played the part well, getting beat up 5-3 and 11-3 in Baltimore.

BTW: For the second straight year, the Orioles won the first two games of the Series after winning their last 11 regular season games and sweeping the ALCS, for an overall 16-game win streak.

Fortunes turned, however, as the Series moved to Pittsburgh. Pirates pitching unexpectedly rose to the occasion, allowing just nine total Baltimore hits through the next three games at Three Rivers Stadium. Steve Blass went the distance in a Game Three 5-1 win. In Game Four—the first Series game ever to be played at night—21-year-old rookie reliever Bruce Kison went prime time by rescuing starter Bob Miller in the first, clamping down the Orioles for seven innings as the Pirates scratched and clawed their way back to a 4-3 win. And in Game Five, Nelson Briles—an experienced Series veteran with the 1967-68 St. Louis Cardinals—completely silenced Baltimore with a two-hit shutout, 4-0.

The Orioles barely staved off elimination in Game Six, needing 10 innings to eke out a 3-2 triumph. Hoping to buck the trend and win on the road—the first six games were won by the home team—the Pirates broke the ice in Game Seven on Clemente’s solo homer in the fourth; an eighth-inning insurance run proved crucial as the Orioles got a run back in the bottom of the inning, but that was it. The Pirates took the 2-1 clincher and captured their first championship since Bill Mazeroski’s famous walk-off triumph in 1960.

BTW: Mazeroski was still a Pirate in 1971, albeit as bench material; he appeared only once in the Series as a pinch-hitter.

World Series MVP Roberto Clemente rounds the bases at Baltimore after putting the Pirates up 1-0 in Game Seven; the Bucs would go on to win, 2-1. (Associated Press)

Roberto Clemente, who was also there in 1960, was a happier camper now. All throughout the Series, the Orioles could not stop the tireless veteran, who raked Baltimore pitching with a .414 average, two doubles, one triple and two home runs. Finally, the light shined very bright on the 37-year old. The chip was gone.

Tragically, barely a year later, so would he.

Forward to 1972: Labor Pains Major league ballplayers go on strike for the first time, leaving behind a bitter taste for angry fans.

Forward to 1972: Labor Pains Major league ballplayers go on strike for the first time, leaving behind a bitter taste for angry fans.

Back to 1970: One For the Brooks The incomparable Brooks Robinson cleans up at third base on the world’s biggest baseball stage for the Baltimore Orioles.

Back to 1970: One For the Brooks The incomparable Brooks Robinson cleans up at third base on the world’s biggest baseball stage for the Baltimore Orioles.

1971 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1971 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1971 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1971 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1970s: Power to the Player Curt Flood’s sacrificial stand to win free agency opens the door for the biggest challenge yet to the reserve clause, which is eventually shattered—but not without fans suffering from numerous player strikes and holdouts.

The 1970s: Power to the Player Curt Flood’s sacrificial stand to win free agency opens the door for the biggest challenge yet to the reserve clause, which is eventually shattered—but not without fans suffering from numerous player strikes and holdouts.

Bob Locker talks about Charles Finley, Vida Blue, Dick Williams and his experience playing for the 1969 Seattle Pilots.

Bob Locker talks about Charles Finley, Vida Blue, Dick Williams and his experience playing for the 1969 Seattle Pilots.