THE YEARLY READER

1993: The Last Great Pennant Race

Both 100-game winners, the San Francisco Giants and Atlanta Braves give a glorious fight for one playoff spot as owners prepare to split league divisions and increase postseason competition.

Before the 1993 baseball season had even begun, it looked as if the Atlanta Braves already had the World Series wrapped up.

Having lost the Fall Classic the last two years and hungry to take that final victorious step, the Braves spent the offseason snagging one of the two prime free agency catches: Reigning Cy Young Award winner Greg Maddux. The acquisition left many in baseball convinced that Atlanta had created its own level of unmatched power; in fact, Maddux’s addition to the Braves’ starting rotation seemed almost embarrassing, given that it was already considered the National League’s best before his signing.

The San Francisco Giants, on the other hand, were just happy to still be in town. Local investors had come to the rescue late in 1992, putting forth a deal to keep the Giants in the Bay Area. It allowed baseball owners to nix a pending sale that would have moved the club to perennial big-league wannabe St. Petersburg, Florida.

The new San Francisco management, led by grocery tycoon Peter Magowan, pleasantly stunned Giants fans by catching the other big fish in the free agency pond: Multi-MVP outfielder Barry Bonds. Still, many predicted the Giants to be no better than a .500 team, providing no threat to the Atlanta juggernaut.

Playing the St. Pete Card

With a 45,000-seat domed facility lying in wait, St. Petersburg, Florida became every major league team’s favorite bargaining chip when angling for a new ballpark back home. Sometimes it was more than a bluff, as Tampa Bay residents twice believed they really got their team—only to be denied at or beyond the eleventh hour.

Atlanta’s expected walk in the park in the NL’s Western Division instead became a tense race to the wire with the equally and suddenly dominant Giants. It was a fight to the finish for which only one team could survive; those were the rules of the game, written up long ago and since never meddled with. There would be no reward for second place, no backdoor entry into the postseason and, heaven forbid, no wild card—an appropriately alien concept to baseball.

But not for long.

The season-long duel between the Braves and Giants—a mammoth struggle between two 100-game winners in which every game mattered to the utmost—would be the last of its kind.

The NL West race was non-existent to start. The Braves sputtered out of the gate, thanks to a problem that no all-world pitching staff could remedy: Weak hitting. Meanwhile, the Giants blasted miles ahead into first place. Bonds was tearing up the league as expected, but there were surprises within the supporting cast. Infielders Matt Williams and Robby Thompson were enjoying unusual .300 campaigns; starting pitchers John Burkett and Bill Swift were steamrolling on a pace to win 20 games apiece; and burly, scruffy-haired closer Rod Beck had developed into an intimidating presence on the mound. By the All-Star break, the Braves had crawled back into second place, but still trailed the rampaging Giants by over 10 games.

Then a fire was ignited—almost literally—upon the Braves’ bats.

On July 20, the Braves scored a coup in acquiring first baseman Fred McGriff from the San Diego Padres, a franchise in the midst of a budget-saving fire sale that would have impressed Connie Mack. But hours before McGriff’s first game as a Brave, the press box at Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium accidentally caught fire, and before it was put out, some 1,000 seats and several radio booths had been rendered useless. The fire, however, provided a symbolic gesture for the Braves’ offense, which suddenly lit up. McGriff’s home run that evening sparked an 8-5 comeback win over St. Louis, and Atlanta began to rocket upward.

BTW: San Diego, on its way to 101 losses, also dealt away Gary Sheffield—prompting a class action lawsuit by Padres fans who felt they were misled by a management promise not to trade away the team’s stars.

As the Braves fired up, the Giants cooled—then iced over at the worst possible moment. Atlanta came to Candlestick Park at the end of August and swept four games from the Giants, suddenly securing first place. The Giants continued to slump, but then pulled themselves back into a first-place tie with the Braves going into the regular season’s final weekend.

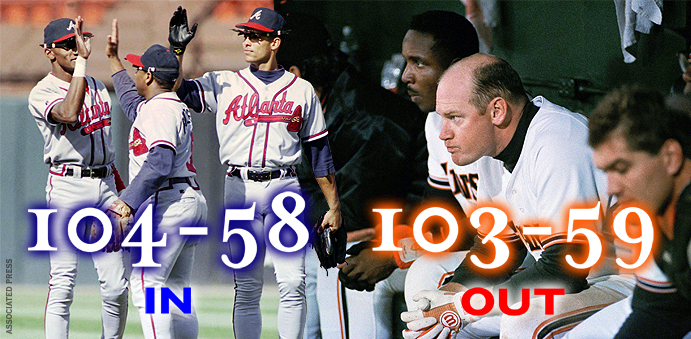

The Braves took the first two games of their final series—a three-game home stand against the expansion Colorado Rockies—while San Francisco kept pace with three road wins at Los Angeles against its hated rivals, the Dodgers. That left both teams with identical records of 103-58 entering the season’s final day.

The Giants rested their season’s hopes on Salomon Torres, a highly touted, 21-year-old call-up whose earlier few appearances upheld his promise. But Torres bombed as the Dodgers dismantled the Giants, who were forced to fold their cards with a 12-1 loss. Meanwhile, the Braves collected, finishing off a Colorado team for whom Atlanta would not lose one game all year—a NL first for the century—and clinched the NL West.

BTW: Torres would go on to have a long major league career—primarily as a reliever—but after his pressure-packed loss to the Dodgers, his lofty potential was never fulfilled.

The Braves’ second-half surge was eye opening. Pre-McGriff, they were 53-41; with him, they were 51-17. His addition was enough to take the pressure off other Braves hitters, who were all badly slumping. David Justice, Ron Gant and Terry Pendleton all came alive with McGriff’s arrival. On the mound, Greg Maddux, after a middling 7-7 start (in spite of a 2.88 ERA), finished at 20-10 with a 2.36 ERA—and collected his second straight Cy Young Award.

For the Giants, 103-59 wouldn’t cut it for the postseason; someone else was simply better. Fair is fair. The intensive, celebrated battle for first place in the West packed such a wallop that it was, in itself, a valid form of playoff—and kept baseball fans everywhere glued to its everyday status. But while this titanic combat played itself out, the owners collectively began re-writing the rules.

For 1994, baseball would scissor each league up into three divisions, adding a new round of postseason play with four playoff participants per league—three division winners and a “wild card” representing the team with the best second-place record. No longer would any two teams with 100-plus wins likely fight to the death; instead they would live to play another day in the postseason, possibly against one another. It removed substance from the regular season, regressing it into a prolonged waiting period, except for marginal teams with no business of being in the playoffs getting the chance nevertheless.

BTW: The owners voted 27-1 for the expanded divisions, an expanded postseason and a wild card. The lone dissenter: George W. Bush of the Texas Rangers.

100 And Out

With the arrival of the wild card a year away, the 1993 Giants were certain to become the last team in baseball annals to win 100 games and not make the playoffs. Here’s a list of other great ballclubs who reached triple digits in victories, yet failed to advance to the postseason.

For all its thrills, chills and comebacks, the NL West race would become much ado about nothing come World Series time.

Unlike the Braves, the Philadelphia Phillies’ roadmap to the NLCS was a much smoother ride. NL East cellar dwellers the year before, Philadelphia quickly gelled itself together, finishing comfortably ahead of the talented yet evolving Montreal Expos. The Phillies were a cohesive yet raucous bunch; when they released clean-shaven, Mormon-bred slugger Dale Murphy, first baseman John Kruk put it succinctly: “There goes the last bit of sanity on the ballclub.”

The rough-and-tumble types on the Phillies included center fielder Lenny Dykstra, who furnished a strong spark for the offense by batting .305 with 143 runs—most in the NL since 1932; Kruk (.316 average, 100 runs); and catcher Darren Daulton (24 home runs, 105 RBIs). But the epitome of the Phillies had to be Mitch “Wild Thing” Williams, an effective closer as proven by his 43 saves. But when he wasn’t in control, ouch. He nevertheless was a pivotal catalyst in the Phillies’ success.

Williams would definitely make an impact during the NLCS against Atlanta, saving two games for the Phillies while winning two more—but not by design. He blew save opportunities after relieving starter Curt Schilling, later named the series’ MVP with a 0.69 ERA—and a 0-0 record. Deep inside, Schilling boiled over the scenarios Williams had made of his efforts.

Despite being out-hit and out-pitched, the Phillies extinguished the Braves’ blazing momentum. After falling behind two games to one, they won the next three to finish Atlanta off. The Braves’ dream of reaching the top would again have to be put on ice.

Waiting in the wings for Philadelphia at the World Series were, once again, the Toronto Blue Jays. The defending champs had little problem repeating as AL East leaders, then as AL pennant winners.

Toronto’s opponents in the ALCS, the Chicago White Sox, had finally and easily reached first place in the AL West after four years of steady improvement. Despite being armed with the AL’s stingiest pitching staff and a solid offense built around massive young superstar Frank Thomas, the upstart White Sox succumbed in six games to the Blue Jays, who simply showed too much experience.

BTW: The White Sox’ top three pitchers—Jack McDowell, Alex Fernandez and Wilson Alvarez—combined to win 55 games while losing only 27.

The Blue Jays’ average pitching staff was well compensated for by a devastating offense. Devon White (116 runs, 34 stolen bases) and Roberto Alomar (.326 average, 55 stolen bases) set ‘em up; Joe Carter (33 home runs, 121 RBIs) and Paul Molitor (.332, 22 home runs, 111 RBIs) knocked ‘em in. By signing with Toronto, Molitor savored the chance of playing for a champion after 15 years of opportunity in Milwaukee passed him by. His departure to Toronto upset Brewers star Robin Yount—who believed Molitor would re-sign with Milwaukee—to the point that it may have influenced Yount’s decision to retire at the end of the year.

Coming out of the woodwork to give Toronto an eye-opening boost was 24-year-old first baseman John Olerud. A left-handed hitter with an excellent eye (and a survivor of a brain aneurysm in college), Olerud achieved sudden attention by exploding to the top of the statistical charts, batting .400 at the All-Star break before “slumping” to a season-ending .363 mark. His 24 home runs and 107 RBIs (not to mention his 54 doubles and 114 walks) surprised those who figured he provided only garden-variety power.

The merging of two offensive powers proved to be no letdown in the World Series. Both teams scored runs in record bunches. Game Four alone provided enough excitement to adequately feed an entire series, ending in a seesaw 15-14 Toronto win.

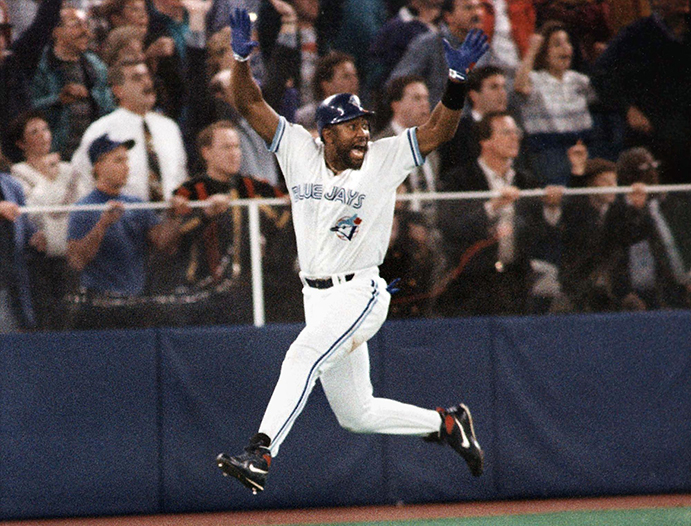

The Blue Jays led three games to two going into Game Six at Skydome, but trailed the Phillies 6-5 in the bottom of the ninth. Mitch Williams was called upon to save the day for Philadelphia and help ensure a seventh game, but the Wild Thing was in an ugly mode. He allowed two runners to reach base with one out, and then Joe Carter came to bat. On a 2-2 pitch, Wild Thing fired a fastball low—but not low enough to keep Carter from golfing it into the left-field bleachers. Toronto repeated as world champions, and the best team in baseball remained north of the border. This triumph, clinched at home and in their final at-bat, felt all the more sweet.

Joe Carter bounces for joy after launching only the second walk-off home run to win a World Series—resulting in the Blue Jays’ second straight world title. (Associated Press)

Walking Off Into Glory

Joe Carter‘s World Series-winning blast would represent the only time one swing brought a team from behind and into the clubhouse with a Series triumph. Listed below are other season-ending, Series-winning hits, all of which broke up tie games.

Molitor would especially enjoy the moment. His .500 batting average (including two doubles, two triples and two home runs) would give him Series MVP honors. Williams, on the other hand, was the categorical Phillies goat, losing twice while sporting an abysmal 20.25 ERA.

The postscript on the Phillies went beyond discouraging. Williams’ teammates, led by Schilling, publicly grumbled behind his back; “fans” terrorized his residence, phoning in death threats and egging his front windows, vilifying his World Series performance while not reminding themselves of his exceptional efforts that helped get the Phillies there.

Perhaps in a fit of mercy, the Phillies traded Williams to Houston during the offseason. Psychologically damaged, Wild Thing would never be the same, bouncing from one team to the other before giving it up for good in 1997.

Forward to 1994: The Year That Should’ve Been Record-breaking quests, unlikely team revivals and an entire postseason are done in by a devastating player strike.

Forward to 1994: The Year That Should’ve Been Record-breaking quests, unlikely team revivals and an entire postseason are done in by a devastating player strike.

Back to 1992: Truly, A World Series After years of strong play, the Toronto Blue Jays finally reach the top and become baseball’s first international champions.

Back to 1992: Truly, A World Series After years of strong play, the Toronto Blue Jays finally reach the top and become baseball’s first international champions.

1993 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1993 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1993 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1993 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1990s: To Hell and Back Relations between players and owners continue to deteriorate, bottoming out with a devastating mid-decade strike—souring relations with fans who, in some cases, turn their backs on the game for good. Recovery is made possible thanks to a series of popular record-breaking achievements by ‘class act’ stars.

The 1990s: To Hell and Back Relations between players and owners continue to deteriorate, bottoming out with a devastating mid-decade strike—souring relations with fans who, in some cases, turn their backs on the game for good. Recovery is made possible thanks to a series of popular record-breaking achievements by ‘class act’ stars.

Erik Johnson recalls a personal baseball journey that included one second-place finish after another—including his brief time as a member of the 1993 Giants.

Erik Johnson recalls a personal baseball journey that included one second-place finish after another—including his brief time as a member of the 1993 Giants.