THE BALLPARKS

Citi Field

QUEENS, NEW YORK

(WikimediaCommons—Malrite)

An owner known more for his dubious Wall Street ties than his nostalgic Brooklyn upbringing built a ballpark that shouts Ebbets Field up front, steel bridge trusses in the back and the ongoing soap opera that is the New York Mets in the center, providing head-shaking theater no matter how much they brought in the fences to generate artificial offense. But as long as the Shake Shack remains open, Mets fans will better accept Citi Field for the inharmonious ballpark that it is.

The first impression of Citi Field greatly depends on how you approach it. If you’re driving off the Van Wyck Expressway behind the ballpark, you bear witness to an incohesive jumble of steel, brick, and advertising panels backing scoreboards and light standards. But for those on the other side hopping off mass transit—may it be the subway or railroad—you come face-to-face with the ballpark’s more formal and exquisite frontage, one that intentionally recalls Brooklyn’s fabled Ebbets Field with its tall, arched openings performing a sharp, elastic bend around an entry rotunda that serves as a de facto shrine for the late, great Jackie Robinson, the headstrong trailblazer of baseball desegregation and American inclusion.

The first impression of Citi Field greatly depends on how you approach it. If you’re driving off the Van Wyck Expressway behind the ballpark, you bear witness to an incohesive jumble of steel, brick, and advertising panels backing scoreboards and light standards. But for those on the other side hopping off mass transit—may it be the subway or railroad—you come face-to-face with the ballpark’s more formal and exquisite frontage, one that intentionally recalls Brooklyn’s fabled Ebbets Field with its tall, arched openings performing a sharp, elastic bend around an entry rotunda that serves as a de facto shrine for the late, great Jackie Robinson, the headstrong trailblazer of baseball desegregation and American inclusion.

At this point, fans begin to wonder: Is this the home of the New York Mets or Brooklyn Dodgers? New York City’s five boroughs are unique in their self-sustaining pride, so a tribute to Brooklyn in the heart of Queens may be hard for some to digest. Mets fans held their own beef when Citi Field opened in 2009, wondering aloud, “What about our team?”

Fred Wilpon, the Mets’ owner behind Citi Field’s mini-obsession with Brooklyn, the Dodgers and Robinson, sold to multi-billionaire Steve Cohen—who’s helped merge the ballpark with memories of the team that actually plays there. Thus, Mets fans feel more at home in Citi Field, which they’ve gradually come to embrace in spite of its structural inharmony and all things inherited from Shea Stadium, the Mets’ former home next door—including the swirling winds, the low-flying jets heading into nearby LaGuardia Airport, and the Mets’ continued masterclass in misadventure.

Citi Field’s main entry, named after Jackie Robinson, is modeled after the rotunda at Brooklyn’s old Ebbets Field—except it’s over twice as big. Mets owner Fred Wilpon, a native Brooklynite, said the entrance reminded him of “walking through the (Ebbets) rotunda, eight or nine years old, holding my dad’s hand.” (Flickr—Wally Gobetz)

Leave It to Hizzonner.

The seeds for Citi Field began being planted in the mid-1990s, and Wilpon already had a strong vision of what the ballpark would look like—a view that, apart from a retractable roof included on an early architect’s model, would stay consistent all the way through to its completion. It’s easy to understand why Wilpon had Ebbets Field on the brain; he was born and raised in Brooklyn, threw batting practice for the Dodgers, was a high school pal of Sandy Koufax, and his wife eventually worked as a secretary for Branch Rickey, the Dodgers’ front office guru instrumental in bringing Jackie Robinson into the major league fold.

New York mayor Rudy Giuliani, who himself grew up a mile from Ebbets Field before evolving into a big-time Yankee fan, nevertheless touted the positives in helping to fund a new ballpark for the Mets, as well as the Yankees, throughout the late 1990s. Even after the horrifying attacks by Islamic terrorists that brought down both World Trade Center skyscrapers on September 11, 2001, Giuliani—at the time seen as a heroic and popular political figure via his hands-on responses to the tragedy—didn’t slow down his zeal to get the new ballparks built.

In December, Giuliani announced a formal—yet non-binding—agreement to build retractable-roofed venues for the Mets and Yankees, each costing $800 million. “Baseball is a tremendously big business,” Giuliani insisted. “It’s like keeping the Stock Exchange here.” The mayor’s rah-rah appeal rang hollow to New York citizens understandably still traumatized by 9-11; economics professor Robert Baade perhaps spoke for many of them when he told the New York Times that Giuliani’s handshake deal struck him as “insensitive and ill-timed at this particular juncture.”

Michael Bloomberg agreed. Taking over for Giuliani early in 2002, New York’s new mayor poured cold water on the ballpark plan, saying he had bigger priorities such as housing, schools, and restoring 20 million square feet of lower Manhattan office space decimated by 9-11—all while facing a $4 billion budget deficit. But four years later, with New York well into recovery mode, Bloomberg had a change of heart thanks to the city’s ambition to host the 2012 Summer Olympics, which could only succeed by building massive new sports infrastructure. Initially shut out of the Olympics picture, the Mets were thrusted back into it at the 11th hour when a proposed facility on the West side of Manhattan, to be used as a main Olympic stadium before becoming home to football’s Jets, fell apart. Redirecting their focus on abundant space next to Shea Stadium, officials sought out a new venue which, afterward, would be converted into a ballpark for the Mets while Shea was demolished—the same scenario that gifted the Atlanta Braves with Turner Field following the 1996 Summer Olympics.

While New York’s Olympics dream died—London beat out the Big Apple for the 2012 Games—the effort didn’t quell the momentum toward building something new for the Mets and Yankees. Within a year, everything was agreed to—this time, with signatures on paper.

The Mets would put up roughly $400 million to help get their new park built, much of that tapping into tax-exempt city bonds; another $614 million, mostly from city coffers, would go into surrounding transportation infrastructure, garages and parks. It got even sweeter for the Mets; the team would pay no rent or property taxes (despite the fact that the ballpark sat on public land) and would accrue all parking revenue up to $7 million per year, whereas the city grabbed it all back in the Shea days.

The Citi Field logo (left), and the patch worn by Mets players during the ballpark’s inaugural season (right). The generic nature of the patch was born out of the team’s reluctance to spotlight Citigroup, the ballpark sponsor bailed out by the Federal government after teetering on total collapse during the subprime mortgage crisis; taxpayers fumed that their money might go to Citi’s annual $20 million payment to fulfill its naming-rights obligation with the Mets.

Follow the Money—And Good Luck Finding It.

With the ballpark approved and its look long since determined, public attention shifted to one remaining question: What’s it going to be named? Fans gave some interesting opinions. Some thought it should be named after Jackie Robinson. Another fan, thinking cleverly, suggested that Met Life would be a suitable naming-rights sponsor. Then there was a fan who felt Trump Field could be a nice fit. “His name is everywhere,” he mentioned.

Fred Wilpon pretty much had his mind already made up. Counting numerous people at Citigroup among his friends, he cozied up to the Manhattan-based banking giant and, even without putting the ballpark name up for bid, secured a staggering 20-year, $400 million deal to place its name on the Mets’ new yard; it was, at the time, easily the biggest naming-rights deal for any sporting venue. A well-followed Mets blogger criticized the new ballpark name, Citi Field, as “embarrassingly corporate and soulless.”

Little did the blogger, nor most anyone else, have any idea of just how soulless things would get.

With Citi Field’s opening date six months away, the Fall of 2008 would deal a brutal double-whammy of ill-timed events that threatened to upend Wilpon and the team he ran.

The subprime mortgage crisis, which crashed America’s housing market and imperiled the world’s economy, left almost every Wall Street financial institution in danger of collapsing. Some did; Citigroup survived, but lost billions, laid off 100,000 employees and saw its stock dwindle to a micro-fraction of what it had been just a year before. It only survived because the U.S. government pumped in billions of taxpayer money to keep it and other marquee banking corporations afloat.

Citigroup was allowed to honor its naming-rights deal with the Mets, infuriating many who now felt their taxes were being used for something non-essential. Several New York City councilmembers proposed that the ballpark be renamed Citi/Taxpayer Field, while a local radio host suggested “Debits Field.” “The Shea name never had such troubles,” wrote the New York Times.

If all of that wasn’t headache enough for Wilpon, bigger trouble lay ahead. A couple months after the subprime crisis’ peak of panic, Bernie Madoff—a big-time investor and good friend of Wilpon who had secured second-row season tickets behind Citi Field’s home plate—was arrested for a good ol’ fashioned Ponzi scheme that bilked his investors out of billions. It was originally reported that Wilpon himself lost up to a billion dollars from Madoff, while others cast suspicion upon the two as working in cahoots with one another, allowing Wilpon to profit. It was a case of two things being equally false—but the eventual truth would reveal Wilpon as financially struggling to maintain his hold on Mets ownership, hindering the team’s ability to succeed in Citi Field’s early years.

Sticking out from the suite level between first and third base, the Hyundai Club seats offer some of the best views of the game, with special access to gorgeous food offerings that come with the price of the ticket. (The alcohol, however, is not gratis.) (Flickr—Kanesue)

A Little Bit of Everything.

Amid all the external melodrama of lost money, Citi Field was built on budget and on time. Structurally, it was a little bit of everything—brick, granite, limestone and over 12,000 tons of dark gray steel, much of it intentionally exposed with decorative arches in a subtle ode to New York’s iconic bridges. To say that there are three decks, wrapping the field from the right-field foul pole to behind left, and leaving it at that, is too simplified; the middle of those decks, grandly labeled the Excelsior Level, includes an exclusive “patio” section that extends from the 53-suite tier over the field level, between first and third base, while the multi-tiered Caesars Sportsbook at the Metropolitan Market interrupts the flow of seats in the left-field corner. Separated from the main bowl is a small section of bleacher seats behind center field, and there’s a two-tiered bleacher section behind right. In all, there are 28 different types of seating categories within Citi Field, which consists of 42,000 total seats—15,000 less than Shea Stadium, with a much higher percentage set aside for the privileged able and willing to shell out hundreds of dollars to sit there for a single game.

But Citi Field’s pièce de résistance has been and likely always will be its main entry, Fred Wilpon’s modern take on Ebbets Field. The rotunda inside the front gates is more than twice the size of the one that greeted Brooklynites at Ebbets, and contains similar terrazzo flooring only because Wilpon confidently relied on the memory of former Dodgers pitcher Ralph Branca, who apparently said it was so.

The rotunda is named after Jackie Robinson for good reason. Baked into the limestone rim separating the two levels of external arches are the nine values that Robinson lived by, as told by his daughter Sharon: Citizenship, commitment, courage, determination, excellence, integrity, justice, persistence and teamwork. It also includes his most faithful quote, “A life is not important except in the impact it has on other lives.” Pictures of Robinson’s life accompany the content, and several video screens show highlights of his baseball life. Finally, in the back of the rotunda under a pair of escalators sits an eight-foot, 3-D recreation of the blue “42” Robinson wore on the back of his Brooklyn jersey.

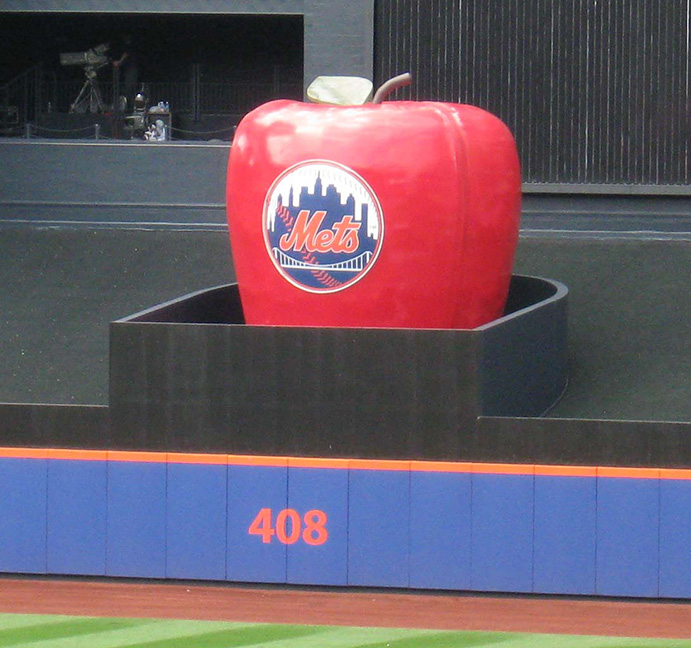

Beyond the Ebbets-centric entry, Citi Field contains nods to other ballparks of lore. The seats are dark green in tribute to the Mets’ first home, the Polo Grounds. Echoing Detroit’s Tiger Stadium, the upper level of right-field bleachers protrudes several feet over the warning track. And, oh yes, Shea Stadium is not forgotten; the foul poles are still Mets orange, the neon New York City skyline has been placed atop the Shake Shack in the ballpark’s “Taste of the City” section behind center field, and Shea’s original Home Run Apple, which popped out of a giant hat when a Mets player hit one out, now proudly yet idly sits in front of the main entrance—thanks to fans who protested the Mets’ original plans to trash it. (A new Home Run Apple, located behind the center-field fence, is four times larger.)

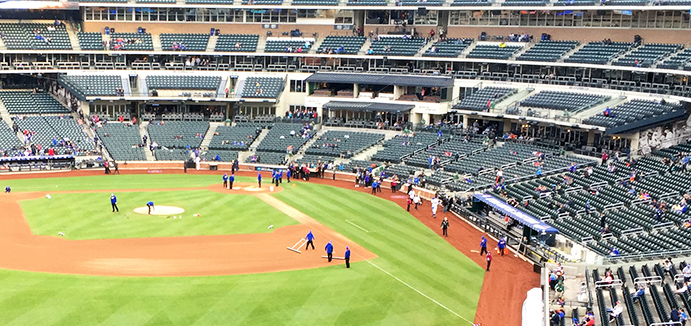

A panoramic view inside Citi Field. Note the arch-like patterns upon the steel used for the light standards and behind right-center field, an aesthetic tribute to New York City’s many bridges. (Unsplash—Tomas Eidsvold)

Mixed Feelings.

Before its official opening, Citi Field was given three games’ worth of dry runs to get everyone acclimated and sort out any unexpected kinks, with a college baseball game pitting St. John’s and Georgetown (drawing 23,000 fans) and two sold-out exhibitions between the Mets and Boston Red Sox. While it was considered a given that ticket prices would be noticeably higher than at Shea Stadium, fans were pleasantly surprised to discover that, by and large, concession prices were actually a tad cheaper. Those sitting in the back rows of the upper deck behind left field and near the right-field foul pole were less thrilled with the fact that they didn’t have full views of the action, with parts of the deep outfield blocked from their vantage point. With a structural rebuild obviously ruled out, the Mets ultimately forewarned anyone buying such seats that they might get obstructed views.

Architectural reaction to Citi Field was mixed at best. “Strangely incongruous,” wrote Metropolis Magazine. Architect Scott Hines, noting Fred Wilpon’s pining for his Brooklyn past, argued that Citi Field “mimics the past for no reason other than empty nostalgia…it stands like a lonely movie set, jarringly out of context.” Mets blogger Greg Prince agreed. “It’s a great piece of architecture by itself,” he said, “but you’re in a parking lot pretending that you’re in the middle of Brooklyn sometime before 1957.” New York Times architecture critic Nicolai Ouroussoff wrote that Citi Field is “another reminder of the enormous gap that remains between high design and popular taste.” A similar sentiment came from baseball writer Rob Neyer: “Essentially, Citi Field is a shrine to Jackie Robinson’s value and to naked commerce. Which seems an uncomfortable, vaguely inappropriate combination.”

“Citi Field isn’t a terrible place,” Neyer continued, “but…it could have been so much more.”

Citi Field opened with spacious outfield dimensions and tall walls, leading to a dearth of home runs throughout the ballpark’s early years. Shown here, from Citi’s first season in 2009, is the 16-foot wall in left field—sarcastically labeled “The Great Wall of Flushing.” Eventually, the heights would be reduced and the walls moved in.

“David Wright’s in Trouble.”

On a crisp April evening, the Mets officially christened Citi Field against the San Diego Padres before a packed house. Tom Seaver, who eventually would be the first player glorified in bronze at the ballpark, threw out the ceremonial first pitch to future Hall-of-Fame catcher Mike Piazza. Ironically, in a ballpark initially known for its spacious field dimensions, the Padres’ Jody Gerut led off Citi Field history with a home run. “Maybe they took Seaver out too early,” wrote the Times’ Ben Shpigel.

An orange cat later invaded the field, proving that a feral cat saturation during Shea Stadium’s days somehow survived into the Citi Field era. Fans worried that it was a sign of a curse—never mind that the Mets were cursed enough thanks to Fred Wilpon’s relationships with the crooks and cretins running and ruining New York’s financial community.

Gerut’s leadoff homer hardly convinced him that Citi Field would be a bandbox. On the contrary; as he and the other players wrapped up the first series in the new ballpark, he thought to himself, “David Wright’s in trouble.”

The Mets’ All-Star matinee idol, who annually averaged 30 home runs over his first four full major league seasons, would become the prime epitome of the team’s frustrating inability to generate power at Citi Field. Though Wright would become the first Met to successfully go deep at the Citi, he would hit only four more home runs there through the rest of the 2009 season. Only Daniel Murphy (seven) would hit more in the Citi’s inaugural campaign; the Mets overall hit 49, their lowest home total in 17 years. It wasn’t just the abundance of outfield space, which initially measured 384 feet to the left-field gap, 408 to dead center and a daunting 415 to right-of-center; there was also the outfield wall, which measured anywhere from 11-18.5 feet, giving rise to its nickname, “The Great Wall of Flushing.” While the combination of all of the above kept home runs down, the Mets did set a team home record with 32 triples, and their .274 batting average at the Citi remains the highest in the ballpark’s history. “The distances in the outfield and the power alleys, that’s where you can have some fun in establishing dimensions,” said HOK Sport’s Ben Barnett, Citi Field’s lead architect. “You can create some unique areas where the ball can rattle around a bit.” Or, as the Mets found out, it could just die on a deep fly in an outfielder’s glove.

While Wright adjusted and hit a dozen homers in Citi Field’s second season—claiming he became more of a “pure” player as a result—the distant, tall walls remained a source of stress for many of the team’s other muscular batters. Jason Bay, who hit 36 homers the year before with Boston, signed on with the Mets in 2010 and bragged that he wouldn’t be intimidated by Citi Field. He then proceeded to collect only three homers at the ballpark, beginning a downward spiral for a career that would flame out three years later.

Mets management was initially resistant to bring in the fences, but home runs and wins sell tickets—and the team was doing neither in Citi Field’s infant years. A small-step change was made in 2010 when the center-field wall was shortened to eight feet, followed two years later with a relative giant leap as the fences were moved in at the gaps—15 feet in left, 25 feet in right to basically eliminate the Citi’s version of Triples Alley. The results were telling; home runs increased roughly 30%, triples were halved, and batting averages dropped as outfielders had less area to patrol.

Another major adjustment at Citi Field was made at the request of Mets fans, who felt that the ballpark nostalgically owed more to the Dodgers of Ebbets Field than the Mets of Shea. “All the Dodger stuff,” admitted Fred Wilpon in retrospect to the New Yorker, “that was an error of judgment on my part.” For Citi’s second season, the Mets’ brand gained more respect; the ballpark was splashed with banners and other large photos of Mets greats of the past, the steel pedestrian bridge linking the right- and center-field bleachers was branded Shea Bridge, and the three side gates were named after former Mets Tom Seaver, Casey Stengel and Gil Hodges. (Yes, the latter two played for the Dodgers, but they also managed the Mets.) They even planted orange-and-blue flowers in front of the main entrance.

The most ambitious and enjoyable of the Mets-centric additions came with the opening of the Mets Hall of Fame, which could be accessed through the Jackie Robinson rotunda. It featured plaques of Mets greats on and off the field, memorabilia and video monitors showing famed moments in team history. Alas, in the name of commerce, the Hall was taken over by a team megastore in 2024, with the museum moved to a smaller space behind center field.

In 2023, the Mets unveiled this massive main video board, encompassing a goliath 17,000 square feet of space. It was, at the time it was plugged in, the largest such screen at any MLB ballpark. (Flickr—Wally Gobetz)

Cobwebs of Gloom.

Fred Wilpon experienced a perfect storm of misery in Citi Field’s early years. Abundant injuries and the struggle to adapt to a new ballpark thwarted the Mets on the field. Pricey premium seats close to the action were seldom filled, since much of the wealthy target audience was financially strapped from the Great Recession. But the biggest threat to Wilpon and the Mets was his ongoing legal issues related to his relationship with Bernie Madoff. It was discovered that Wilpon had actually made a $300 million profit from Madoff while the majority of other investors lost virtually everything; it was thus no surprise when Wilpon was sued by Madoff victims seeking not just all of Wilpon’s profit, but an additional $700 million for “willful ignorance,” suggesting that Wilpon had inside knowledge of Madoff’s shenanigans. That larger amount was thrown out by a judge, and in 2012 the two sides settled with Wilpon paying out $162 million.

The chain reaction was inevitable. Wilpon had to slash payroll. That translated to a less competitive team, one that posted losing records in each of its first six years at Citi Field. (Jon Stewart asked: “Where in New York City is the ball dropped every year?” Conan O’Brien answered: “Citi Field.”) The losing translated to diminished attendance, with actual crowd counts well below what was officially announced. The poor turnouts translated to tens of millions lost, season after season. Maybe that orange cat on Opening Day did have something to do with it.

Deep in debt, Wilpon went into near-desperation mode to reverse course. The Mets lowered ticket prices at Citi Field, held postgame concerts featuring the likes of REO Speedwagon and Daughtry, tugged Major League Baseball for multiple loans totaling $100 million, forged more non-baseball events to bring in more revenue, and sold off 49% of the team—maintaining a bare majority of control—bringing on investors such as comedian Bill Maher, 1-880-Flowers.com CEO Jim McCann, and a hedge-fund billionaire named Steve Cohen. Wilpon even wanted to build a casino in the Citi Field parking lot, a request declined by New York City officials because the lot wasn’t on tribal land. A group of fans, done with Wilpon’s financial frailty, gathered enough cash together to buy a billboard near the Citi imploring the Mets owner to sell. “Ya Gotta Leave,” it said, paraphrasing Tug McGraw’s famous rallying cry for the 1973 Mets.

Finally, in 2015, luck turned in the Mets’ favor. Maybe it was a new main scoreboard. Maybe it was a further reduction in the right center-field gap by another 10 feet, which would prove helpful for Mets hitters who belted more home runs in that area than their opponents. More than maybe, the Mets’ first playoff appearance at Citi Field—resulting in their first NL pennant since 2000—was largely the result of a starting rotation featuring three young guns (Matt Harvey, Jacob deGrom and Noah Syndergaard) and portly 42-year-old Bartolo Colon, not to mention a red-hot postseason performance from infielder Daniel Murphy (.421 batting average, seven home runs in nine NL playoff games). Championship dreams for the Mets were spoiled when the opposing Kansas City Royals took the World Series in five games.

The unexpected joyride would be short-lived, as the Mets settled into a mixed bag of success and disappointment in the years to follow, accompanied by tabloid-style moments such as Harvey’s curfew-breaking nights on the town and loveable mascot Mr. Met giving the finger to a gang of verbally abusive Mets fans. But attendance and revenue returned to positive levels, shaking away the cobwebs of gloom that consistently permeated Citi Field’s early years.

Citi Field, alight and alive at night. The outer entry structure was designed to mimic Brooklyn’s Ebbets Field. (iStock)

Gastronomical!

As topsy-turvy as the Mets have been at Citi Field, as fans shrug their shoulders at the ballpark’s architectural schizophrenia, there’s one thing that everyone can agree on: The food is a hit. Since its opening, Citi Field has been listed at or near the top of virtually every poll ranking ballpark perishables.

If you want it, chances are Citi Field has got it. There are at least 10 restaurants and/or lounges within the ballpark, some of them available to all ticket holders. Definitely available for everyone are outlets providing fried chicken, empanadas, barbecue, cheesesteaks, sushi, gryos, tacos, lobster rolls, and many other eats not always associated with ballpark food. There’s even a few bars with bites outside of the gates, but within the ballpark structure: EBBS Brewing by the main entrance, and the K Korner along Seaver Way, both of which are ideal for either a pregame or postgame sip or nosh.

Food options are omnipresent throughout Citi Field, but its sweet spot lies behind center field in the “Taste of the City” square, loyally anchored by Shake Shack—the popular hamburger chain that began as a hotdog cart outside of Madison Square Garden in 2001. It features the famed Bases Loaded Burger, a cheeseburger topped with crispy onions and barbecue sauce. If you really have a Jones for the Shake Shack, be forewarned: So will a lot of other people. The lines can sometimes rival that of a TSA check-in on a busy day at nearby La Guardia Airport, and you’ll likely miss more than a half-inning if you stop by mid-game.

A satellite-view rendering of the Mets’ ambitious plans for Metropolitan Park, a mixed-use development around Citi Field. Many hurdles need to be overcome for the project to become reality, with the Mets particularly crossing their fingers on being given a precious gaming license to include a casino. (Metropolitan Park)

A City Around the Citi.

Fred Wilpon’s decade-long money problem became a thing of the past in 2020 when he sold his majority interest in the Mets to minority investor Steve Cohen, who bought the franchise for an MLB-record $2.4 billion. Cohen exuded gravitas and was not afraid to flaunt his wealth, and why not—his was the largest of any single major league owner. But he was not without his own troublesome business past, with his hedge fund firm having recently paid $1.8 billion in insider trading fines. Looking beyond rather than behind, Cohen viewed a better future for the Mets and Citi Field, stating upon his purchase of the team, “I’m not in this to be mediocre.”

Whereas Wilpon grew up on the Brooklyn Dodgers, Cohen was all Mets. He fell in love with the team when they were loveable losers at the Polo Grounds, staying loyal through their long run at Shea Stadium. Once he got rich, he spent $400,000 on the ball that famously went through the legs of Boston’s Bill Buckner that would help the Mets win the 1986 World Series. Under his watch, Cohen intensified the Mets’ vibe at Citi Field, with more tributes to the greats of Mets past, more uniform number retirements, and holding the team’s first Old-Timers’ Day since 1994. It was reassuring for Mets fans to know that the new guy in charge was bleeding orange and blue, not Dodger blue.

Citi Field would get more than just a new coat of paint under Cohen’s rule. In 2023, the Mets replaced the main video scoreboard for the second time—this time installing MLB’s largest yet at a whopping 17,400 square feet. And the outfield underwent another reduction, with eight feet shaved off in right field to accommodate the brand-new Cadillac Club at Payson’s, a posh, exclusive joint featuring plush seats behind marbled tables with pop-up monitors for those wishing to pay an annual $25,000 membership fee. For that, you get free parking, free food and free alcohol.

Far more ambitiously, Cohen is seeking to convert the vast parking asphalt that surrounds three sides of Citi Field into a mixed-use development with a proposed $8 billion price tag. “The sports and entertainment park New York deserves,” as Cohen calls it, would include bars, restaurants, a hotel, a music venue, parkland, athletic fields and a casino—if the Mets can win a lottery and be granted one of three gaming licenses currently up for grabs from New York City officials. And where will all the parking spaces go? Stacked up, in a series of multi-story garages.

Metropolitan Park, as Cohen is currently calling the project, will be adjacent to another large mixed-use development approved early in 2024, one that does not involve the Mets. Located across the street from the east side of Citi Field, it will consist of a soccer stadium for Major League Soccer’s NYCFC, a hotel, public school, and housing units for both lower-income and homeless families/individuals. Besides ridding the existing triangular area of its current status as a blighted collection of auto body shops that the New York Times once described as looking like “a neighborhood in a developing country,” this revamped area, along with Cohen’s Metropolitan Park, if fully realized will finally give Citi Field what it and Shea Stadium before it never truly had: Neighbors.

Just because Citi Field is, for the moment, virtually alone in its own neighborhood doesn’t mean that the Mets are the facility’s lone source of entertainment, with quite the menu of non-baseball events. Many soccer matches have been hosted by the ballpark, including its status as a fallback for NYCFC when its default home, Yankee Stadium, is being used by the Yankees. An outdoor hockey contest was held on New Year’s Day 2018 between the New York Rangers and Buffalo Sabres. There’s also been cricket, hurling (not the kind involving beyond-soused Mets fans), an ultra-Orthodox Jewish rally, and the draw for the 150th Belmont Stakes, held in the spacious second-level establishment behind home plate currently entitled Piazza 31 Club.

Of course, there have also been concerts. Of course, the first at Citi Field was fronted by Paul McCartney, whose Beatles introduced the world to stadium rock when it came to Shea Stadium in 1965; a double album of songs from his three shows in July 2009, called Good Evening New York City, was later released. Other acts at Citi Field have included Beyonce, the Korean boy band BTS, and a classic rock festival featuring Fleetwood Mac, the Eagles, Steely Dan and Journey, among many others.

New York’s own Lady Gaga has performed twice at the ballpark—once formally, in 2017, and once very informally when, scantily clad during a 2010 Mets game, her erratic behavior sitting in the front rows attracted unwanted attention and forced security to move her to an unused suite owned by comedian/Mets fan Jerry Seinfeld, where she continued her rebellious act by flipping off fans. Seinfeld later responded, “You give people the finger and you get upgraded? Is that the world we’re living in now?”

Citi Field’s Home Run Apple pops out of hiding, as it always does after a Mets player hits a home run. Four times larger than the one used at Shea Stadium, the Apple was one of the few representational relics leveraged from the Mets’ days at Shea; fans complained that little attention was given to honor Mets heritage when the new ballpark opened. That changed after the Citi’s first few years; for instance, the outfield wall shown here below the Apple was repainted in blue with orange trim, in accordance with the Mets’ branding palette. (Wikimedia—Richiekim)

Charismatic, Yet Imperfect.

Citi Field remains a young ballpark, surrounded by nothingness—unless one considers asphalt and grungy auto repair shops an emotional kind of “something.” Whether the inevitable evolution of its surroundings will be matched by enhancements within the ballpark is a fuzzy assessment, but as the Mets are contracted to stay there through 2047, standing pat is not an option—especially so long as the team remains the property of a billionaire many times over.

Rob Neyer was right: Citi Field could have been so much more. Perhaps, in time, it will be. But for now, Mets fans will embrace it as a charismatic yet imperfect ballpark, much like the team they root for and, at times, love to hate.

In other words, it’s a perfect marriage.

The Ballparks: The Polo Grounds Peculiar doesn’t even begin to describe the Polo Grounds, a bathtub of a ballpark that yielded pop fly home runs and tape-measure outs as it led almost as many lives as a cat against the rocky bluffs of Harlem. Through its resiliency manifested more than its share of baseball’s legendary moments and unforgettable actors, whether it was McGraw, Mathewson, Merkle, Master Melvin, Mays or, yes, even Marvelous Marv.

The Ballparks: The Polo Grounds Peculiar doesn’t even begin to describe the Polo Grounds, a bathtub of a ballpark that yielded pop fly home runs and tape-measure outs as it led almost as many lives as a cat against the rocky bluffs of Harlem. Through its resiliency manifested more than its share of baseball’s legendary moments and unforgettable actors, whether it was McGraw, Mathewson, Merkle, Master Melvin, Mays or, yes, even Marvelous Marv.

The Ballparks: Shea Stadium Never mind the jet packs and monorails. Shea Stadium represented the Space Age to New Yorkers freed of their rotting baseball relics of yesteryear, proudly serving as the center of the Gotham entertainment universe until early neglect threatened to turn it into a black hole. Good times or bad, you could always count on a high-decibel din courtesy of diehard Mets fans and the airliners roaring overhead.

The Ballparks: Shea Stadium Never mind the jet packs and monorails. Shea Stadium represented the Space Age to New Yorkers freed of their rotting baseball relics of yesteryear, proudly serving as the center of the Gotham entertainment universe until early neglect threatened to turn it into a black hole. Good times or bad, you could always count on a high-decibel din courtesy of diehard Mets fans and the airliners roaring overhead.

New York Mets Team History A decade-by-decade history of the Mets, the ballparks they’ve played in, and the four people who are on the franchise’s Mount Rushmore.