The Ballparks

The 1960s-1980s: The Cookie Cutter Monsters

Multi-purpose stadiums become the rage as a line of enclosed facilities adaptable to disparate events welcome in baseball teams fleeing decaying ballparks and inner cities.

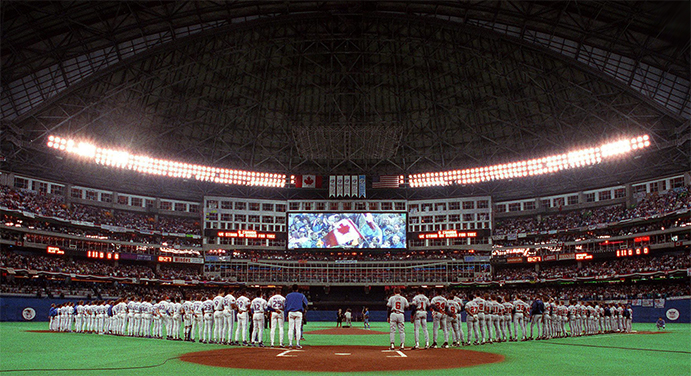

Toronto’s Skydome (now named Rogers Centre) was the last of the multi-purpose giants, a modern retractable-domed facility complete with a Hard Rock Café and a hotel with rooms looking out onto the field. (Associated Press)

The westward move of the Dodgers and Giants to California touched off an unprecedented land grab within the majors; from 1961-1977, there were 10 new franchises and five relocations. Big league baseball could now be found anywhere, from Atlanta to Montreal to San Diego to Seattle.

For baseball owners, it wasn’t the good’ ol days anymore. You couldn’t build a ballpark on the cheap, as labor and materials costs had shot venue construction from the hundreds of thousands 50 years earlier to the tens of millions in the 1960s. Finding the ideal spot also proved a challenge as available land wasn’t as plentiful as it used to be. But the owners did have one important piece of leverage: The ability to threaten a move out of town by expressing their unhappiness with the status quo. The local politicians got the message and went into the business of building new facilities to keep from being remembered as the leaders who lost their cities’ baseball teams.

For baseball’s owners, it was understood that this new wave of publicly funded sports venues would come with concessions. First off, these would not be ballparks. They would be multi-purpose stadiums, built with more than just baseball in mind as pro football began to command equal (if not greater) popularity over the National Pastime. For the architects, who by and large were locally-based and nationally known, this presented a challenge: How to reconcile a rectangular football field with baseball’s pizza-slice dimensions and make the seating sightlines equally optimal for both. In almost every case, this was solved by creating an enclosed, circular structure akin to the Roman Colosseum with lower decks designed to swivel apart from baseball’s V-shape to face each other across a football field.

The second concession would irk players and purists to no end: The birth of artificial turf. Given the practical and financial challenges of maintaining a field partially covered by the moveable lower stands, fake grass became a necessity at many of the new stadiums. The players hated it. Their knees took a pounding from a hard surface slightly softer than asphalt; their legs, elbows and arms endured “carpet burns” from sliding catches; and they had way too much time to think just how in the world they were going to throw out a runner while awaiting a hundred-foot hop hit off the bouncy turf. At the height of its reign in the mid-1970s, artificial turf covered four of every 10 facilities used by major league teams.

These “concrete donuts” were wholly modern civic achievements remarkable more for their size than beauty, all but indistinguishable from one another. Even the names were similar, as those who confused Cincinnati’s Riverfront Stadium with Pittsburgh’s Three Rivers Stadium will attest. “I stand at the plate in Philadelphia,” said the Pirates’ Richie Hebner, “and I honestly don’t know whether I’m in Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, St. Louis or Philly.” The kitschy factor was nil. The outfields were symmetrical, the fence heights the same. There were no beer gardens. No traces of ivy. No quirks. No signs that said, “Hit it here.”

Pittsburgh’s Three Rivers Stadium, rounded and enclosed with artificial turf and lower seating that flexed from baseball to football, could have easily been confused for a number of other similarly-constructed stadiums of the time. (Jerry Reuss)

More curiously, the stadiums seemed to reflect the society of the times. Ballparks once embraced the city, absorbing themselves into the urban environment as if they had organically sprouted from the soil. But the 1960s and 1970s brought rampant inner-city crime, counterculture and a shattering of the public trust via Vietnam and Watergate. People wanted to escape from it all—and the stadiums, enclosed and shut off from the outside and surrounded by vast parking lots acting like protective moats, may have been their sanctuary.

The blandness of the open-air facilities would be offset by the spectacular debut of the domed stadiums. No sports venue during this era spawned more chatter than the Houston Astrodome, a fantastic architectural statement that, unlike the other new stadia of the 1960s, spared no expense in the grandest of Texan traditions. The air-conditioned Astrodome included cushioned seats, a vast, electrical celebratory display, the first modern luxury boxes, a garish presidential suite and a bowling alley.

The Astrodome was the first of five major league domed facilities to open over the next 25 years. All five had different roof designs; all five had problems. In the Astrodome itself, the glare of translucent roof panes made finding a fly ball almost impossible for fielders to spot; once painted, the lack of sunlight killed the grass. Ceiling tiles fell from the Seattle Kingdome’s thin concrete roof; severe weather occasionally tore holes in the Minneapolis Metrodome’s fabric roof; the retractable lid at Toronto’s Skydome (now Rogers Centre) sometimes didn’t work, while the one at Montreal’s Olympic Stadium never did.

Amid the multi-purpose mania, there were a few new ballparks. Los Angeles’ Dodger Stadium and Kansas City’s Royals (now Kauffman) Stadium, ironically titled as “stadiums,” were the only two baseball-specific facilities to survive as such between 1960-90; Anaheim Stadium and San Francisco’s Candlestick Park, two other venues constructed solely with baseball in mind during this period, were later expanded and reconfigured to accommodate neighboring football teams. (Anaheim Stadium downsized back to baseball-only in 1997 following the departure of the NFL’s Rams to St. Louis.)

Forward to the 1990s-2010s: Coming Home Oriole Park at Camden Yards opens the door for a new wave of ballpark construction as teams return to their roots and embrace yesteryear with a clever eye toward massive revenues.

Forward to the 1990s-2010s: Coming Home Oriole Park at Camden Yards opens the door for a new wave of ballpark construction as teams return to their roots and embrace yesteryear with a clever eye toward massive revenues.

Back to the 1930s-1950s: Dormancy Depression and war embolden the general attitude of most major league teams to contentedly sit it out at their existing ballparks, which undergo expansion and are outfitted with lights for the night.

Back to the 1930s-1950s: Dormancy Depression and war embolden the general attitude of most major league teams to contentedly sit it out at their existing ballparks, which undergo expansion and are outfitted with lights for the night.