The Ballparks

RFK Stadium

Washington, D.C.

(Photographs in the Carol M. Highsmith Archive, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division)

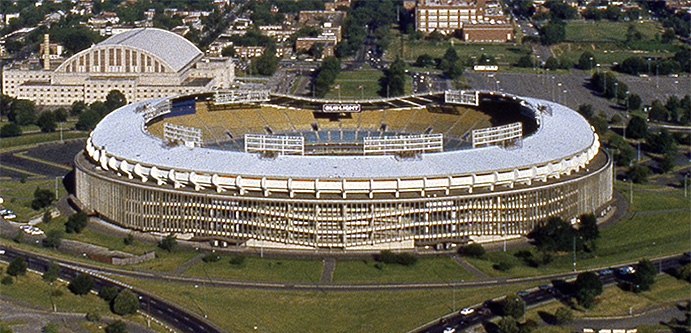

Built by the Federal Government on the same straight line that’s home to the U.S. Capitol and other historic American landmarks, RFK Stadium was conceived to enjoy a similar, lofty stature—and even though it was hog heaven for football fans, it became a fractured limbo for the baseball gods who suffered few ups and many downs within the venue’s roller coaster-shaped rooflines.

Luck is not everything in baseball. But it’s close. The right-place, right-time dynamic within this great game has been blessed upon certain players and teams throughout history; others, meanwhile, have been cursed at the opposite end of the spectrum. Nolan Ryan once fielded the league’s best earned run average despite an 8-16 record. The San Francisco Giants won 103 games in 1993 but were denied a piece of the postseason action. The Boston Red Sox, time and time again, had ultimate victory snatched away by the jaws of defeat. And there was, of course, Lou Gehrig, the Iron Man, who described himself as the luckiest man on the face of the Earth even as a savage illness was about to cut him down before the age of 40.

Major league ballparks have also experienced the thrill of luck, both good and bad. And few, if any, facilities have been dealt a worse hand than RFK Stadium.

Seating roughly 45,000 for baseball, RFK was given an admirable location at the very east end of a esteemed horizontal corridor that includes, as you move west, the U.S. Capitol, Capitol Mall, the Washington Monument and the Lincoln Memorial. It’s almost as if the stadium was imagined by its Federal planners as a noble addition to these esteemed landmarks and give the D.C. sports scene long overdue dignity.

RFK would be the perfect tonic for pro football’s Washington Redskins, who thrived at the stadium for 35 years. Baseball’s relationship with the venue would be something altogether different—a broken alliance full of disappointment, tease, unfulfilled hope and more disappointment. As RFK did its part to make baseball work, baseball clearly did not.

Ike Likes, Ike Inks.

The idea to build a “last-word-in” type of facility within the District of Columbia was born out of Congress during the New Deal days of the Great Depression. But nothing took serious hold until 1945 with an effort led by Mississippi Senator Theodore Bilbo, a relic of Civil War days in mind if not in body whose standing as the head of the D.C. committee made him the closest thing to Washington’s mayor before the city was allowed to have one. The largely black D.C. population surely didn’t see eye-to-eye with Bilbo (who wasn’t afraid to spout off about “niggers” in front of the microphones), but they along with the rest of the district’s citizenry must have been overwhelmed with what he had in mind: A 200,000-seat mega-stadium with an aluminum roof held up inside by air pressure (a process similar to how the Metrodome worked in Minneapolis) and access from multiple methods of mass transit; the plan even called for a adjacent airstrip for private craft, in a time before no-fly zones. The ambitious weight of the project, which would have been built at the same spot as RFK, collapsed the effort.

After Bilbo, the stadium concept was mothballed for another decade until Congress set aside money to establish a National Stadium Commission in 1956. The urgency to build something was never greater; Griffith Stadium, constructed and owned by the Washington Senators and rented out to the Redskins, was a deteriorating warhorse from Deadball Era days with a haphazard, modular structure that would have looked at home in a shantytown. Worse, it was buried away in a worrisome part of town with almost no parking for cars, the preferred choice of spectators as the postwar age boomed onward. As franchise movement became more of a reality within baseball, there were rumors that the Senators were looking elsewhere to play, potentially leaving the Redskins locked out of a closed ballpark. A new stadium would hopefully keep both teams happily in town.

On September 7, 1957, Congress earmarked $6 million in Federal taxpayer money to build what originally would be called D.C. Stadium, with President Dwight D. Eisenhower signing the bill. Everyone seemed enthusiastically onboard—except for, curiously, the Washington Senators. Clark Griffith, who had owned the American League franchise since 1919, likely would have embraced the new stadium as he embraced Washington through thick and (mostly) thin for decades—but he had died two years earlier, and nephew Calvin Griffith, heir to the Senators’ throne, was now itching to take the team out of town. He probably would have already succeeded, but a planned move to Los Angeles after the 1956 season was thwarted by a threatened lawsuit from team stockholders demanding that the Senators stay put. Even with D.C.’s modern new stadium a sure thing, Griffith was cool to the idea of becoming a tenant, because he wouldn’t get a dime of revenue from parking and perishables; he also didn’t like the stadium’s location, preferring a more vernal plot of land in Rock Creek Park on the north side of town.

Griffith tried to negotiate for a better cut of the earnings, but he knew there would be little budge from a stadium run by the D.C. Armory Board, an asset of the U.S. Military. He therefore figured he could get a better deal elsewhere—and sure enough, he got one in Minnesota, where he moved the Senators late in 1960 just three months after ground broke on D.C. Stadium. The American League, feeling pressure from the possibility of a third circuit (Branch Rickey’s Continental League) and local politicians seeking revenge for the Senators’ departure by rethinking the validity of baseball’s hallowed antitrust exemption, quickly caved and presented Washington with one of two expansion franchises for 1961—the first such movement within baseball in over 60 years.

It Slopes Here, Slopes There, Slopes Everywhere.

Relieved that the multi-purpose facility would actually serve multiple purposes with the new team (also called the Senators) in the fold, D.C. Stadium’s overseers continued construction without pause. It would be the first of the so-called “Cookie Cutter” stadiums, a purely circular structure with a set of moveable stands that swiveled 90 degrees from the third-base side for baseball to the outfield to accommodate football. It would be more intimate than many of the multi-purpose stadia to follow with a cantilevered (no posts below) upper deck, where 70% of the seats would be situated, hovering above the field level. Pros: Few would sit too far away from the action. Cons: More field-level spectators would have their views of high fly balls cut off by the overhangs, while upper deck fans seated behind the outfield couldn’t see down to the warning tracks and walls, unless they were in the first row.

RFK Stadium’s exterior consists of an extended lower edifice exposing wavy pedestrian ramps partially concealed by equally spaced vertical pillars; atop is the upper deck roofline, which swirls up and down as a parabolic mirror image of the ramps’ movements below. From a distance, some have mistaken RFK’s undulating heights for an elaborate roller coaster, while others have referred to it as a soggy straw hat. With East Capitol Street splitting from its long straightaway to curl around the facility, it’s almost as if RFK and its sinuous facades perform some sort of choreographed ballet dance with the surrounding environment.

RFK Stadium’s upper deck supports is given a graceful, art deco-like embellishment. (Flickr—Sarah Stierch)

D.C. Stadium opened in October 1961, too late for the new Senators—forced to give old Griffith Stadium one last gasp of lame duck life—but not too late for the Redskins, who inaugurated the venue early in their NFL schedule and ended up being the guinea pigs for the usual first-event bugaboos such as, in this case, missing seats, drinking fountains with no water and concession stands with no power. When the Senators debuted at the new stadium in 1962, they would stumble upon some of their own issues. As the expansion team expectedly sank in the standings, so unexpectedly did the field they played on; portions of left-center field literally sloped down to six feet until it was solidified and leveled off.

Paint It White, Frank.

RFK played fair for both hitters and pitchers, with a symmetrical layout measuring 335 feet down the lines, 380 to the power alleys and 410 to straightaway center. Only one guy made it look small: Frank Howard. The 6’7”, 275-pound monster, brought on by the Senators in 1965 after a trade from the Los Angeles Dodgers, arguably emerged as the majors’ most proficient slugger of the late 1960s and acquired nicknames from Senators fans such as the Capitol Punisher and the Washington Monument. Howard averaged 43 homers a year from 1967-70 as pitchers otherwise dominated, and he monopolized the all-time power numbers at RFK, drilling 116 homers at the stadium—with Don Lock’s 51 representing a very distant second place.

Howard provided a solution for upper-deck outfield fans frustrated in their inability to view the whole field; he merely brought the action right into their laps. There eventually would be 24 upper-deck seats painted white, denoting the exact spots where Howard’s tape-measure shots would land. The longest of all of them came on September 24, 1967, when Howard boomed one 535 feet high into the wooden, ochre-colored seats.

There would be no pitching equivalent to Howard for Senators fans to idolize, because most of the hurlers weren’t very good. In fact, beyond Howard, not much of anyone on the Senators was. Reliever Darryl Knowles certainly tried. Only two other pitchers appeared in more games at RFK than Knowles, and no one there had as good an ERA as Knowles’ lifetime 1.97 mark. Yet few emblemized the frustration of playing for the Senators as Knowles, who in 1970 fashioned a 2.04 ERA with two wins—and 14 losses.

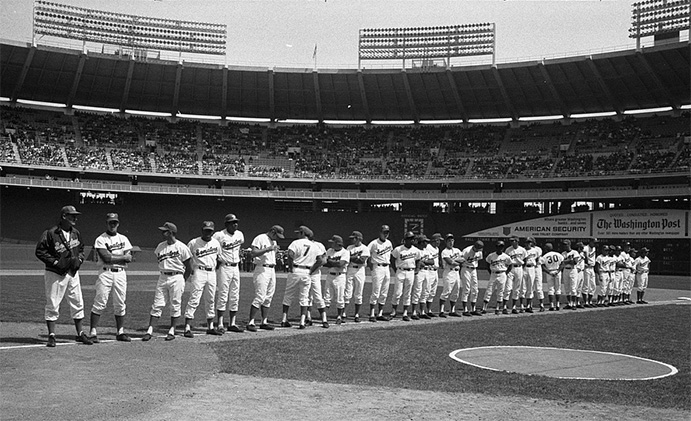

The Opening Day lineup in 1971 for the Washington Senators, ready to spend their tenth—and last—season at RFK Stadium. (U.S. News and World Report Magazine Photograph Collection, Library of Congress)

Short-Circuited.

The second edition of the Washington Senators proved to be just as bad as the first. In their first 10 years, the Senators had one winning record (an 86-76 mark in 1969 under rookie manager Ted Williams), only twice finished above .500 at RFK, and never drew over a million fans. Complicating matters was that the Senators suffered under a series of terrible owners. The last of those was Bob Short, who outbid comedian Bob Hope and other interested candidates late in 1968 to buy the team. There would be no Hope as the Senators came up Short, a Minnesota native (how about that for irony, Calvin Griffith) who made himself general manager, trashed a potentially good roster and complained endlessly about the safety around RFK and the desire to get a bigger slice of the stadium revenue pie as the initial 10-year lease set to expire. When it became apparent that the D.C. Armory Board, badly saddled with debt, wasn’t going to give him what he wanted, Short pulled a Griffith by threatening a move out of town—and delivered on his promise, getting permission from the American League on September 20, 1971 to move the Senators lock, stock and barrel to the Dallas-Ft. Worth suburb of Arlington, where they would become the Texas Rangers.

The few Washington baseball fans still left around to care showed their infuriation at Short 10 days later when the Senators played their final game at RFK before a crowd of 14,460. Vocal fans paraded through the stands with numerous signs and banners highlighting vicious wordplay on Short (“How dare you sell us Short,” “We’ve been Short-changed”), and in the top of the ninth hundreds of younger fans couldn’t help themselves and invaded the field, tearing up and grabbing anything they could, from the bases to chunks of grass. A potential 7-5 win for the Senators became a 9-0 forfeit loss, and the new Senators’ run at RFK came to a fitting end. An elderly woman/Senators fan was asked by the Washington Post what she planned to do in the absence of local baseball, and she replied that she’d be doing “fancy work and puzzles and watching David Frost.”

Unlike a decade earlier, when Griffith took the original Senators out of town, Congress this time didn’t even bother to protest as they waived away the relevance of baseball through the failure of two local major league teams. And besides, just 40 miles to the north they had the Baltimore Orioles, in the midst of a massive run of success under manager Earl Weaver. As for RFK Stadium, there was one tenant the politicos could definitely still rock the rafters over: The Redskins. Though the NFL team totally mirrored the Senators’ on-field ineptness through the first 10 years at RFK—forging a sole winning record in 1969 in the one and only Washington campaign led by legendary coach Vince Lombardi, who died the following year—it still engendered a far more loyal following, filling up RFK every time the team took the field. Football fans were rewarded when, just as the Senators departed, the Redskins became a perennial Super Bowl contender (making five trips over the next 20 years) and, buoyed by their intensive rivalry with the equally powerful Dallas Cowboys (think Dodgers-Giants), became a wildly popular institution at RFK.

High up in RFK Stadium’s upper deck, among the fading wooden seatbacks, are one of 24 seats painted white to pinpoint the spot where one of Frank Howard’s monstrous home runs landed. (Flickr—Rudi Riet)

The Senators’ departure left Washington vacuumed of baseball for the first time since 1900. RFK’s operators sorely missed the National Pastime, and not just for sentimental reasons; even with every ticket being sold for football games, the stadium’s financial books were a wreck. The powers that be—in this case, the U.S. Government—wanted to know why, and so they called the D.C. Armory Board onto the carpet for a series of Congressional hearings that may have lacked Watergate’s importance but certainly not its tabloid factor. It had already been well known that RFK’s revenue could only pay off the nearly $1 million in annual interest on the $20 million in bonds—for which a dime had never been paid—but the hearings revealed an eye-opening level of mismanagement, kickbacks and even prostitution parties related to the building of the facility. The perception that the D.C. Armory Board was morally bankrupt was followed by the reality that it had, by 1973, become financially bankrupt as well; the government had little choice but to take over, gradually pay off the debt and, by 1985, cede control of RFK to the District of Columbia, which only needed to worry about paying for the stadium’s upkeep.

Washington, Anyone?

Baseball’s absence at RFK looked to be short-lived. For their first five years, the San Diego Padres were a horrible failure on a par with the Senators, a volatile mixture of poor ownership, poor attendance and poor performance; it didn’t seem a year went by without a Padres pitcher losing 20 games. When San Diego owner C. Arnholt Smith got into legal hot water over some bad loans and was forced to sell, investors in Washington sprang into action and all but closed the deal to relocate the team east; a move looked so certain that Padres players appeared in promotional photos sporting Washington uniforms (they were to be called the Stars) and Topps printed their first series of 1974 baseball cards with the Padres identified as “Washington, National League.” Out of nowhere came McDonald’s owner Ray Kroc, who bought the Padres, kept them in San Diego, and left RFK empty-handed again.

RFK Stadium during the Washington Nationals’ three-year stay in the mid-2000s. The curvature of the upper deck is evident, reaching its highest point adjacent to both first and third base. (Flickr—The Bitten Word)

More attempts to being baseball back to D.C. were met with failure. In 1976, the National League considered expansion—with Washington as a frontrunner—but voted down the idea. There were rumors of the Oakland A’s, on virtual life support in the final days of Charles Finley’s mercurial rule, relocating to RFK, but nothing materialized. The Orioles considered moving some of their home games to RFK, but never did. In 1978, an oceanographic engineer named Joe Wheeler tried to drum up financial support to buy an existing team through $24 million in public stock and move it to Washington; he fell $23 million short of his goal. Late in the 1980s, a group calling itself DC Commission on Baseball armed itself with 15,000 season tickets pledges and made a presentation to NL owners, who were now ready to expand; it apparently didn’t go well, as the league decided instead on Miami and Denver. Finally, in the mid-1990s, separate Washington groups made their pitches for major league expansion. One was well financed and would use RFK temporarily before moving into a new ballpark next door in Virginia; the other was an African-American group with little money but a desire to stay in D.C. Both lost out to St. Petersburg and Phoenix.

During these lost years, baseball was played at RFK. In 1982, business interests came together and established the Cracker Jack Old Timers Baseball Classic, reuniting retired baseball legends of all ages. RFK remained in its football configuration for the game, partly because it was too expensive (north of $50,000) to shift the moveable stands, and partly because the organizers didn’t think the old-timers could poke it past the shortened (260 feet) left-field fence anyway. They were proved wrong when 75-year-old Luke Appling, who hit just 45 career home runs in a 20-year major league career, sent a Warren Spahn pitch 300 feet into the stands to the approval of 30,000 howling fans. The event, which ran through 1988 at RFK, proved to be a smashing success and showed that D.C. still held great enthusiasm for baseball.

The old timers games helped prod Major League Baseball into returning to RFK—at least to the extent of exhibition play. In the 1980s and 1990s, 16 preseason games would be held at RFK, the last in 1999 highlighted by St. Louis Cardinals slugger Mark McGwire, who a year after smashing the season record for home runs boomed a batting practice drive off the concrete façade arcing over the upper deck. Even Frank Howard would have been impressed.

The Cardinals’ opponent that day would be the Montreal Expos, whose situation was becoming increasingly unacceptable to MLB. A once competitive franchise, the Expos had been reduced to small-budget status, and failure to build a new ballpark to replace the voluminous Olympic Stadium (whose debt issues ran circles around those that once hounded RFK) left MLB to consider folding the team through contraction. When there was too much squawk-back to that idea, MLB instead bought out the Expos—essentially leaving it to be run by the other 29 owners—with the idea that it could find a buyer in another city. Washington was considered the frontrunner for such a move.

This time, the D.C. would not be denied.

RFK Stadium’s narrow and often dark concourses convinced the Nationals that their fans would be better served with a team store placed in a trailer outside of the stadium. (Flickr—Ernie and Katy Lawley)

A National Revival.

Thirty-three years to the day that the Senators played their last game in D.C., MLB made it official: The Expos were being transferred from Canada to RFK, which would serve as a temporary home while a new ballpark was constructed elsewhere in Washington. It would be the first relocation by a major league team since the Senators left RFK for Texas.

RFK officials quickly brushed up and polished the stadium for the return of baseball; fortunately, years before they had replaced the wheels on the moveable stands that had rusted beyond repair, allowing stadium workers to shift the seating back into baseball shape. The field dimensions remained the same, or so it was thought; after several players crushed drives that didn’t clear the walls in the power alleys, it was suspected that the 380 markers were misleading. Nosy sportswriters checked it out, did their pacing from home plate and, sure enough, discovered that the alleys were actually 395 feet away. MLB apparently made an exception for the rule barring midseason adjustments of outfield walls and allowed the fences to be placed at their correct distances.

Enthusiasm exploded over the new team in town, the Washington Nationals—not coincidentally, the name of the last NL team to play in the Nation’s Capitol way back in 1899. A sellout crowd greeted the Nats for their first home date on April 14, 2005—although only half of the crowd managed to make it past intensive screening equipment at the gates before the start of the game because the ceremonial first pitch was being delivered by President George W. Bush. For the year, the Nationals maintained Washington baseball tradition by finishing last in the five-team NL East—but with an 81-81 record, making them the second non-losing team to finish in the basement. It didn’t matter to Washington fans; whereas the 1971 (and last) Senators team drew 20,000 only four times, the 2005 Nationals never drew below 23,000. RFK witnessed 2.7 million fans, which remains a D.C. baseball record—even nearly a decade after the opening of RFK’s replacement, Nationals Park.

In the next two years, the fans’ initial passion for the Nationals waned as did attendance at RFK, as the team played more basement-worthy baseball in the standings. After 2007, Nationals Park was ready to welcome the Nats, and baseball’s association with RFK Stadium finally came to an end.

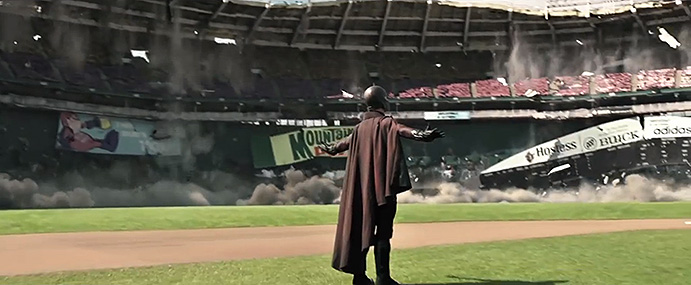

From fictional times comes a moment in 1973 when Magneto telepathically lifts RFK Stadium off its foundation in the 2014 movie X-Men: Days of Future Past. (Twentieth Century Fox/Marvel)

Kickin’ and Crumblin’.

Even without the Nationals, RFK chugged along. With the Redskins having long since left (after 1996) for FedEx Field in Landover, Maryland, soccer became king at the old stadium. Numerous international matches were held at RFK, including several from the 1994 World Cup, and the venue evolved as a favorite hosting ground for the United States national team; on the club level, RFK was home to Major League Soccer’s D.C. United from its inception until 2018 when it, too, bolted to a new, smaller stadium of its own. All that’s left for RFK is an appointment with the wrecking ball, which is expected sometime in 2021. Or, they could hire someone like Magneto, who in X-Men: Days of Future Past used his mind power to literally tear RFK off its concrete roots and plunk it down around the White House.

Soccer fans nearly helped bring down the stadium first. During an international match, media members in the press box were mortified to see a chunk of concrete fall on a ledge in front of them, thanks to overzealous fans jumping on and rocking the upper deck above in unison—a RFK Stadium tradition. Elsewhere, the end was nigh; concrete fell in other spots, bathroom ceilings peeled apart, and the mustard-colored wooden seats in the upper deck cracked away. Even the white paint on Frank Howard’s many landing spots eroded into a near non-existence.

The Nationals carry on elsewhere, continuing a tradition of Washington baseball that was rudely interrupted for a third of a century, a time when it should have shined the brightest. It’s not RFK Stadium’s fault; all it did was sit lonely while poor ownership helped doomed generations of local major league activity, followed by a series of heartbreaking “psych” moments from baseball officials who dangled the promise of the game in front of them, only to take their business elsewhere.

Perhaps people will say that Washington missed out, but with the return of baseball in the form of the Nationals, the fans—and RFK Stadium—showed it was baseball that was missing out all along.

The Ballparks: Griffith Stadium Your ballpark has burnt to the ground and you’ve got three weeks before Opening Day. Quick—whaddyado? Ask the Washington Senators, who performed the ultimate rush job and constructed Griffith Stadium as one of the more architecturally coarse and confusing of venues, with a playing field so distant and awry, the whole outfield became Triples’ Alley. Fans and presidents were nonetheless thrilled by the breathless action between the lines.

The Ballparks: Griffith Stadium Your ballpark has burnt to the ground and you’ve got three weeks before Opening Day. Quick—whaddyado? Ask the Washington Senators, who performed the ultimate rush job and constructed Griffith Stadium as one of the more architecturally coarse and confusing of venues, with a playing field so distant and awry, the whole outfield became Triples’ Alley. Fans and presidents were nonetheless thrilled by the breathless action between the lines.

The Ballparks: Nationals Park Build it on your own dime, and they will come—not just Major League Baseball, but an adjacent community full of new residents flocking to gleaming high-rise developments, ruining the view of D.C. monuments for fans in the stands but re-energizing a once-derelict chunk of town. What Nationals Park lacks in aesthetical wow, it more than makes up in terms of urban renewal and ecological rebirth.

The Ballparks: Nationals Park Build it on your own dime, and they will come—not just Major League Baseball, but an adjacent community full of new residents flocking to gleaming high-rise developments, ruining the view of D.C. monuments for fans in the stands but re-energizing a once-derelict chunk of town. What Nationals Park lacks in aesthetical wow, it more than makes up in terms of urban renewal and ecological rebirth.

Washington Nationals Team History A decade-by-decade history of the Nationals, the ballparks they’ve played in, and the four people who are on the franchise’s Mount Rushmore.