The Ballparks

Yankee Stadium (1923-2008)

Bronx, New York

(Photographs in the Carol M. Highsmith Archive, Library of Congress, Print and Photographs Division)

The House that Ruth Built and Mayor Lindsay Rebuilt, the majestic cathedral otherwise known simply as the Stadium was the last and grandest addition to baseball’s romantic steel-and-concrete era, a towering achievement which emitted a confident aura to its colossal frame. It was the perfect match for a proud and iconic franchise that forever tolerated anything short of a World Series title as pure dishonor.

For any ballplayer called up to the major leagues for the first time, one of the more alluring perks is the opportunity to step upon and play in the great ballparks of the time. Back in the day, the Friendly Confines of Wrigley Field, Fenway Park with its Green Monster and the Old Lady of Schenley Park (Forbes Field) would always qualify among the must-see’s during a big-league baptism.

For any ballplayer called up to the major leagues for the first time, one of the more alluring perks is the opportunity to step upon and play in the great ballparks of the time. Back in the day, the Friendly Confines of Wrigley Field, Fenway Park with its Green Monster and the Old Lady of Schenley Park (Forbes Field) would always qualify among the must-see’s during a big-league baptism.

But the awe cast upon players walking into Yankee Stadium for the first time was an entirely different experience, leaving an impression to last a lifetime. Its stately, voluminous frame, expansive spaces and cavalier ambiance was not unlike one’s first visit inside St. Peter’s Basilica, or the Roman Colosseum, or Yosemite Valley.

The forces behind Yankee Stadium made no bones about its grandiose appearance. Shaft the intimacy, they said; you play in a ballpark, we play in a stadium. After all, eternal reign requires more than a cozy little space to play your imperial brand of ball.

To be apt, the Stadium transcended the narrowly focused concept of being a baseball-only venue. It was primarily built for baseball, true—but it hosted a galaxy of other events, many of them as memorable as the myriad of great moments served up by the New York Yankees.

The Stadium is where legendary Notre Dame football coach Knute Rockne made his famous “Win one for the Gipper” halftime speech, before his Fighting Irish revved up and defeated the rival Army team. It’s where African-American boxing great Joe Louis needed all of two minutes to knock Nazi-sponsored Max Schmeling out for the count. It’s where the National Football League came of age in a watershed 1958 title game won in overtime by the Baltimore Colts over New York’s football Giants. It’s where, in 1965, Pope Paul IV delivered the Western Hemisphere’s first papal mass—an event cleverly recalled as the “Sermon on the Mound.” It’s where Nelson Mandela, the South African activist just released after 26 years in prison, spoke triumphantly to 100,000 in 1990. There was also rodeos, opera, Irish hurling, beauty pageants, a mass gathering of Jehovah’s Witnesses (who personally and meticulously cleaned up the stadium after they were done using it), concerts by the likes of Billy Joel, U2 and Pink Floyd, and a one-year appearance by soccer icon Pele and the New York Cosmos.

But of course, the Stadium is best known for the Yankees. In 84 years at the original (and rebuilt) structure, the Bronx Bombers won a staggering 37 American League pennants and 26 World Series titles. They won at least 50 games at home 47 times; they never once lost 50. But those are just numbers; the memories are what many best remember about the Stadium. Lou Gehrig’s heartbreaking farewell speech. Record-breaking home runs from Babe Ruth and Roger Maris. Perfect games by Don Larsen, David Wells and David Cone. Reggie Jackson’s three home runs on three swings in the 1977 World Series. Twelve-year-old Jeffrey Maier’s glove assist on Derek Jeter’s 1996 playoff homer. The raising of the tattered American flag from the World Trade Center while a reassuring President George W. Bush threw a ceremonial first strike during the 2001 World Series, post-9/11.

While more charming ballparks such as Wrigley, Fenway and Ebbets Field hold a special place in the hearts of nostalgic baseball fans, few will argue against Yankee Stadium’s one-of-a-kind standing as a massive, supreme and unapologetically corporate facility.

Might From Spite.

Five years before Yankee Stadium opened, it would have been unthinkable for a team like the Yankees to conceive of something so ambitious. Since their arrival in 1903, the Yankees were an afterthought on the New York baseball scene, a weak and obligatory symbol of Big Apple representation in the American League. The franchise had no charisma, little success and sparse support. Its ballpark, the mundane, hastily-built Hilltop Park near the northern tip of Manhattan, was all but built in a day for a dollar. The team found unlikely company at Hilltop in 1911 when the New York Giants—thriving on the flip side as one of the majors’ elite franchises—needed a temporary home after the burning down of their wooden ballpark, the Polo Grounds. Two years later, the Giants—on their way to winning yet another National League pennant at a steel-and-concrete rebuild of the Polo Grounds—encouraged the Yankees to move into their place. And why not? The 10-year lease the Yankees signed provided extra money and a rudderless tenant for the almighty Giants.

In 1915, the Yankees received an upgrade when ownership switched to the “Two Colonels”—Jacob Ruppert and Tillinghast Huston—who weren’t seeking to retain the franchise’s second-class label. Progress finally became an option with the Yankees—slowly, at first, and then fast and furious at front page-headline strength in 1920 when the team acquired Boston Red Sox wunderkind Babe Ruth for a then-staggering $125,000. Overnight, the Yankees had become a monster sensation in New York; Ruth hit a record-lapping 54 homers—nearly twice the previous mark he himself set the year before—the Yankees earned long-overdue relevance in the pennant race, and they became the first team to draw a million fans (1,289,422, to be exact) over one season.

All of this became too much for John McGraw, the Giants’ diminutive and feisty manager. He had hated the Yankees’ presence in New York ever since they replaced the Baltimore Orioles, a charter AL franchise that McGraw himself ran and then tried to bury when a feud with AL strongman Ban Johnson went nuclear. That the Yankees now had Ruth grated even more at McGraw, because he felt he’d been stiffed on a deal to acquire the pitcher-turned-slugger from the minors back in 1914. Charles Stoneham may have owned the Giants, but McGraw was the franchise’s fiery heart and soul whose opinions carried huge weight. The Yankees’ lease on the Polo Grounds was up in a couple of years; backed by McGraw’s spite, the Giants told them that once it expired, they’d have to pack up and go someplace else. To McGraw, “someplace else” represented a forced exile from Manhattan, where potential ballpark land was all but non-existent; the Yankees could chance it across the Harlem River in the Bronx—or “Goatland,” as McGraw called it.

In their search for a new ballpark site, the Yankees checked out Manhattan anyway. They eyed a spot about a mile southwest of the Polo Grounds where the Jewish Orphan Asylum was looking to sell, but the acreage was too small—and even if the Yankees were good with it, the asylum would have nixed the deal anyway because it objected to any buyer intending to sell alcohol. Next, the Yankees looked at building a venue over the tracks at Pennsylvania Station near Midtown, but the U.S. military vetoed the idea because it needed the space for existing anti-aircraft gun artillery to protect rail commerce.

Outside of Manhattan, the Yankees vetted a property across the East River in Long Island City and realized that, to make it work, they’d have to buy surrounding factories and shut them down to eliminate the nauseous odors they pumped out. Finally, someone threw out the concept of a floating ballpark that would move around Manhattan, but the Two Colonels didn’t think the idea would hold water.

In the end, the Yankees found their sweet spot in the Bronx, virtually walking distance from the Polo Grounds across the Harlem. The 10-acre site, a lumber yard purchased for $600,000 from the William Waldorf Astor estate, lay amid an undeveloped portion of the Bronx strewn with boulders, weeds and haphazard fencing. But a transportation grid had been laid out; paved streets created one empty block after another, while the #4 subway line, constructed just a few years earlier, connected the Bronx with Manhattan as it emerged out of a tunnel and right up against the proposed stadium site. Perhaps John McGraw envisioned the area as Siberia, but city planners, backed by data that saw a four-fold population increase in the Bronx over 20 years, saw it differently; the placement of a prestigious new yard for the Yankees would only accelerate growth in what would eventually be known as the Concourse neighborhood.

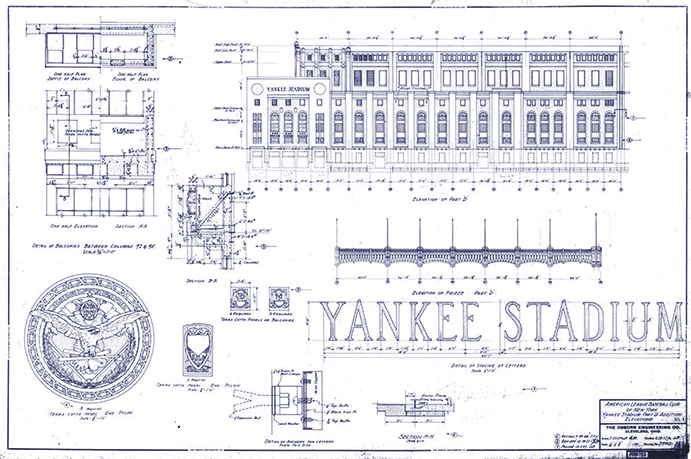

This blueprint developed by Yankee Stadium architect/builder Osborn Engineering shows wonderful detail of the main entry elements, the general exterior, and the iconic frieze façade atop the third deck.

Hail, Yankees!

As gargantuan as Yankee Stadium would become in comparison to all the other existing parks of the time, it was initially designed to be even bigger—an enclosed three-tier behemoth packing in at least 75,000 fans, a capacity nearly twice as big as the largest major league crowd to date. Scaling back to accommodate a $2.4 million budget, the Yankees settled for an unprecedented tri-level grandstand that stretched short of each foul pole, with the lower level down the third-base line extending further around the left-field pole. The tiers were supported by 118 steel vertical beams that would cause visual obstacles for fans seated behind them; the concrete used to complete the structure was a special mixture whipped up by the Edison Portland Cement Company, founded by famed inventor Thomas Edison.

While most other ballparks of the steel-and-concrete boom relied on noted architects, Yankee Stadium’s look and feel was the responsibility of Osborn Engineering, noted more for its construction abilities. But Osborn nailed it, designing a structure that befitted—and perhaps helped cement, no pun intended—the eminent Yankee mystique. From outside its front gate, the Stadium beheld a bulky and fearless pose, an impenetrable beige-soaked fortress calmed by tall arched windows fitted with louvers for ventilation. Its three main grandstand entries consisted of rectangular slabs with “Yankee Stadium” spelled at top in dignified, all-capped serif type, surrounded on each side by a specially-designed Yankee coat of arms. Overall, the Stadium’s exterior came off as a cross between Wall Street and Ancient Rome.

But unquestionably, the Stadium’s architectural signature was to be found inside, draped atop the upper deck. The art deco frieze, made of copper and painted a cool, light industrial green to compliment the darker green seats, hung gracefully at the top of the stadium even if the length between each arc varied. Without it, the Stadium’s mighty interior would have looked aesthetically ordinary.

Yankee Stadium revealed as much ingenuity as immensity. It was the first major league ballpark to use scissor ramps to help ferry out a potential big crowd. The giant, manually-operated scoreboard, wedged between the elevated subway tracks and the 20,000-seat wooden bleachers, was the first to display inning-by-inning scores of other games. And its playing field included what was initially termed a “running track” that encircled the entire playing perimeter; it was, in fact, baseball’s first warning track, backed in the outfield by a slow-rising grass berm reminiscent of Cincinnati’s Crosley Field. The track allowed large vehicles to truck in building blocks for other events such as boxing and the circus—keeping them off the grass, to huge sighs of relief from the Stadium’s groundskeepers.

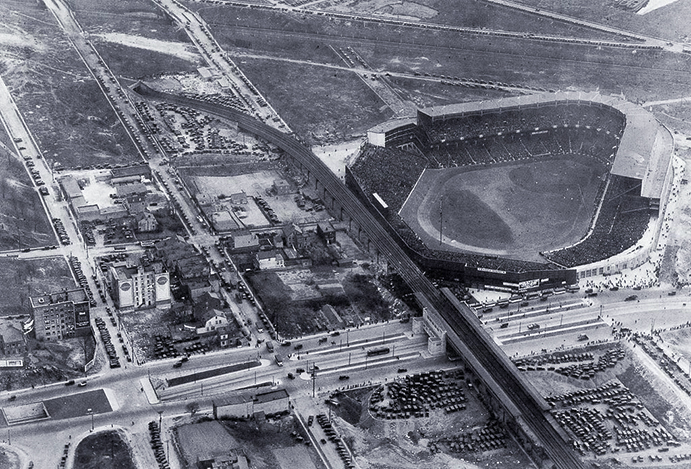

When Yankee Stadium opened in 1923, the surrounding area was far from developed with only a smattering of buildings and, pivotally, the passing by of the #4 subway train from Manhattan. Needless to say, the area would fill in—and rather quickly—after the Stadium’s opening.

The House That Ruth Built.

Completed in a less than a year and two months ahead of schedule, Yankee Stadium would be the last privately-financed major league ballpark built for nearly 40 years. Jacob Ruppert, who bought out Tillinghast Huston’s share of the Yankees during construction to become the team’s sole owner, was prodded to have the Stadium named after himself, as was the custom at other recently-opened ballparks—but he preferred “Yankee Stadium” because it was his players, not he, who deserved the credit for making it a reality. Those players would certainly come to justify Ruppert’s modesty.

On April 18, 1923, Yankee Stadium was inaugurated with an overflow crowd of 64,000—it was initially reported at 74,000, but the Yankees later recalibrated the figure—as another 20,000 were turned away. The pregame ceremony featured Stars and Stripes Forever creator John Philip Sousa, conducting the Seventh Regiment marching band—which would feature repeatedly at the Stadium for decades to come. New York Governor Al Smith threw out the ceremonial first pitch. Blustery conditions made the first pitch reading of 49 degrees seem even chillier.

For Yankee fans, the first game couldn’t have followed a more agreeable script. Bob Shawkey went the distance, scattering a run on three hits as the Yankees prevailed over the visiting Red Sox, 4-1. All of New York’s runs were tallied in the third inning; Babe Ruth, who said beforehand that “I’d give a year of my life if I can a hit home run in the first game in this new park,” collected on his wish—capping the rally with a three-run drive that cleared the short right-field wall. The New York Times referred to Ruth’s blast as a “savage home run that was the real baptism of Yankee Stadium.” Famed sportswriter Fred Lieb had a more memorable take, describing the Stadium in the next day’s papers as “The House That Ruth Built.”

Like Steve Rogers transforming into Captain America, the Yankees in 1923 completed a five-year ascension from baseball’s forgotten lightweight to superhero—or evil imperial king, if you were rooting for someone else. They had the best team, the best player, and now the best facility—even if attendance actually dropped from the year before, though that can be partly attributed to a cakewalk 16-game finish atop the AL standings. The season culminated with the Yankees taking the World Series over the Giants in six games, which surely added to McGraw’s animus of the Yankees. Jacob Ruppert reveled in the afterglow of his championship triumph, the first of 20 experienced by the Yankees over a 40-year stretch—and he sneered back at McGraw’s desire to shoo them back toward irrelevancy. “The fans of New York will go where there is a first-class ball club playing the sort of baseball people want,” he told The Sporting News.

Life was good for the Yankees. And it would be for a long time to come.

Yankee Stadium’s exterior, shown here during its first game, dwarfed for sheer size other major league ballparks of the time; it quickly and rightfully drew comparisons to the Roman Colosseum. (The Rucker Archive)

Sea of Humanity.

The Bronx grew up quickly around Yankee Stadium after its opening. The vacant blocks surrounding the facility were filled in and property values shot up as the area became a developed extension of the borough’s glitzy Grand Concourse section several blocks to the east and north. Nearby retail shops took advantage of the Yankees’ presence, such as drug stores that set up dining counters for patrons to grab a lunch before heading over to the Stadium for a typical 3:00 start. Residential buildings behind the bleachers and subway tracks rose high enough for tenants to watch games from the rooftops.

The Stadium itself hardly stood pat early on. As Ruppert bemoaned over the lost revenue of thousands turned away from sold-out Yankee World Series contests, he immediately looked at extending the upper two decks. He finally did so after the 1927 Yankees’ magical 110-44 regular season run and World Series sweep of the Pittsburgh Pirates, curling the tiers around the left-field foul pole; the right side would follow suit in 1936, concurrently with the removal of the original wooden bleachers in favor of a steel-and-concrete replacement. The upgrades increased overall capacity from 58,000 to over 70,000.

When there weren’t enough seats at the Stadium, the Yankees occasionally let in as many as they could possibly manage through the gates. The sea of humanity reached its peak on September 9, 1928 when 85,265 jammed into the Stadium to watch a crucial doubleheader against the Philadelphia Athletics—a twinbill the Yankees swept to take control of a thrilling pennant race. But a year later, Ruppert rethought and nixed the SRO policy after a downpour during a sold-out game on May 19 led to a stampede of fans from the uncovered bleachers; two people were killed and 62 others injured in the rush to find cover.

Death Valley, Monument Valley.

Unlike other ballparks of the time, the Yankees never allowed a spillover of fans onto the field, whether behind ropes or upon temporary bleachers—this, in spite of Yankee Stadium’s massive expanse of playing area.

The Yankees took the general dimensions of the bathtub-shaped Polo Grounds—with its sub-300-foot distances down the lines and voluminous space between the gaps—and slanted them to the left. This made life easier for dead-pull hitters and the left-handed Babe Ruth, who had less of a reach to right field (296 down the right-field line, 350 to straight right) than those shooting out toward left. Though the Bambino was strong enough to be a home run king playing in any major league park, Yankee Stadium didn’t necessarily pad his power stats as some might think; he essentially collected an equal number of homers (259) in his 12 years at the Stadium as he did during this same time on the road (252).

Part of the reason Ruth didn’t hoard more homers at the Stadium was due to the über-distant reaches to the gaps and center field that killed off some of his longer deep flies. But right-handed power hitters had it particularly tough—squinting their eyes to look out at outfield wall markers reading 460 feet to left-center and 490 to straightaway center; this vast territory would soon garner the nickname “Death Valley.” Reconstruction of the bleachers in the late 1930s would whittle those dimensions down to 455 and 461, but the Valley remained an ambitious target.

Located in front of Yankee Stadium’s 461-foot wall marker in center field were three monuments, in memory of (from left to right) Lou Gehrig, Miller Huggins and Babe Ruth. Some believed that the late Yankee legends were actually buried underneath them.

The furthest reaches of center field already had a flagpole in play in front of the wall, but it got company in later years with the addition of three monuments, in honor of Yankee greats who died far too early. The very first monument was for pint-sized manager Miller Huggins, who led the Yankees to six AL pennants and three world titles before succumbing to blood poisoning late in 1929. The third would be dedicated to Ruth, who passed in 1948. In between, the second monument was for Lou Gehrig, who debuted at the Stadium during its first year, became a regular at first base in 1925 after predecessor Wally Pipp developed the worst-timed headache in baseball history, and developed into an ironclad sidekick (if not equal) to Ruth and, later, DiMaggio. Gehrig was riding a record consecutive-game streak of 2,130 games early in 1939 when, shockingly, he had to bow out of the lineup as he became increasingly ravaged by a muscular weakness that, two years later, would kill him at the age of 38. A few months after his last game, Gehrig had a special day held in his honor at the Stadium and, in a tearfully short speech that represents the venue’s most heartbreaking moment, spoke humbly and declared that despite a “bad break” he was the “luckiest man on the face of the Earth.”

The monuments, made of red granite, were mistaken for headstones by those who thought those honored were actually buried beneath them. And while some questioned the wisdom of cementing hard objects in the middle of a playing field, the Yankees felt that their placement, close to 450 feet away from home plate, minimized any chance that outfielders would become unwilling participants in a game of human bumper pool. Inevitably, players would have to navigate around and between the monuments to chase down line drives that invaded the space; perhaps the most memorable play in the area occurred in 1939 when DiMaggio, chasing a deep drive from the bat of Detroit’s Hank Greenberg, sped behind the monuments and flagpole and, 460 feet away from the plate, leapt against the wall to make the catch. Less memorable was a futile effort during a 1958 game by Washington rookie Albie Pearson, who took forever to hunt down a ball behind the monuments. Senators infielder Rocky Bridges waited so long for Pearson, he later quipped, “I thought Miller Huggins was going to throw me the ball.”

Yankee Stadium’s voluminous playing field was surrounded by a “running track” that would later be identified as the majors’ first warning track; beyond it, a grass berm elevated slightly toward the bleachers. (Library of Congress)

Wake Me Up When the World Series Starts.

Astonishingly, despite winning eight pennants and seven more World Series titles over a 15-year period from 1931-45, the Yankees during this time never once drew over a million fans to the Stadium. There were outside factors at play: First the Great Depression, then World War II. Perhaps there was also some complacency from Yankee fans who could no longer feel championship euphoria like the very first time. While it was tough to draw fans to the Stadium for a midweek game against a lowlife like the St. Louis Browns, the Yankees could still pack ‘em in for a big event. The World Series certainly qualified; case in point had to be the 1943 season, when the team drew a Stadium record-low 618,330 fans for 77 regular season games—but brought in a third of that for just three World Series contests against the St. Louis Cardinals.

Yankee fans also came out in droves for special events tied to the games. The special day for Lou Gehrig drew over 61,000; a 1942 wartime doubleheader brought in 69,136, not so much to see the visiting Washington Senators but a between-game attraction in which 54-year-old ex-pitching legend Walter Johnson dueled from the mound against 47-year-old Babe Ruth. The old timers’ appearance netted $75,000 for the war effort, and Ruth answered by, unofficially, hitting his last home run at the Stadium.

For six years after Ruppert’s death in 1939, the Yankees were financially overseen by his family’s trust while long-time executive Ed Barrow ran the baseball side of things. Barrow was excellent at sensing talent and keeping the wins coming, but he nor anyone else paid much attention to marketing efforts, explaining the status quo that existed around the Stadium in terms of facility improvements, etc. That changed in 1945 when Barrow and the bank sold to a trio of prime movers: Proactive executive Larry MacPhail, Arizona-based construction magnate Del Webb, and Dan Topping, a playboy of sorts who was married to Sonja Henie, Norwegian skating star and future subject of an obscure Caddyshack joke.

Initially, Webb and Topping were mere money men who helped finance the $2.8 million purchase of the Yankees; it was MacPhail who took the ball and ran with running the enterprise. He wasted no time; a $600,000 makeover of the Stadium was initiated, which included the repainting of the venue, dressing up of the entry rotunda, placement of new (and wider) box seats, and the addition of two auxiliary scoreboards on the outfield wall. The Yankees also became a somewhat late arrival to the nighttime scene, after Barrow had previously decried the idea of night fixtures as a “wart on the nose of the game.” But MacPhail, who with the Cincinnati Reds 10 years earlier introduced the majors to night ball, lit up the Stadium with 14 games under the lights in 1946 with illuminating results, averaging nearly 50,000 per game. It helped spark already healthy attendance in the Yankees’ first postwar campaign as the team became the first to pass over two million in season attendance.

MacPhail also invented the Stadium Club, a posh restaurant, lounge and (at the time) largest bar in New York state underneath the field level seats. It was a baseball first, and very exclusive; to enter, you had to buy one of only 400 available memberships that entitled you to access and, oh yes, a box seat above. Members would receive their Club cards in a leather case, and their name would be placed on a plaque attached to their seats. The initial $600 fee would also give purchasing members the right to other Stadium events such as boxing and football. In its first year, the Stadium Club sold out, with 200 applicants denied; The Sporting News referred to the Club as the “Stork Club, Copacabana, El Morocco and all the rest rolled into a baseball amalgam.”

One other lasting tradition that MacPhail started was Old Timer’s Day. This wouldn’t be Babe Ruth and Walter Johnson performing a little batting practice. Old Timer’s Day would be something much bigger: A two-inning exhibition between a full squad of former Yankee greats, playing against legends from other teams. The first affair, played in front of 23,000 before the Yankees’ final home game of 1947, brought out a who’s who of Hall of Famers including Ty Cobb, Cy Young, Tris Speaker, Jimmie Foxx, Lefty Grove, Lefty Gomez, Herb Pennock and Mickey Cochrane. The pregame event was such a hit that it left no doubt for an encore the following year—and then the year after that, and so on, all the way to the present day at the new Yankee Stadium. The old folks, as great as they once were, had to understand the limitations of advanced age; in 1951, 65-year-old Frank “Home Run” Baker tripped and fell flat on his face while running down the line to beat out a ground ball. Fans and teammates held their breaths as Baker looked lifeless for more than a few seconds, but he eventually bounced back up.

The second Old Timers’ Day was, alas, the saddest. Babe Ruth, wrecked by throat cancer, found enough strength to put on the #3 jersey one last time and, using a bat as an ad lib cane, slowly walked out to home plate; the crowd of 50,000 serenaded him with Auld Lang Syne. Two months later, he was gone; for two days, Ruth was given a sendoff worthy of a head of state, his body lying in rest inside the Stadium rotunda as 100,000 passed through to pay their final respects.

The interior of Yankee Stadium during the 1927 World Series. The copper frieze saved the overall design from appearing too industrial or plain. (The Rucker Archive)

The Stadium Merry-go-Round.

Larry MacPhail cashed out to Del Webb and Dan Topping following the 1947 World Series—won again by the Yankees, over the Brooklyn Dodgers—but without MacPhail the team just kept on turning the turnstiles and winning. They drew at least two million through the Stadium gates every year from 1946-50 and, starting in 1949, won the first of an unprecedented five straight World Series.

Webb and Topping carried on and anchored down the corporate Yankee atmosphere, drawing comparisons of the franchise to U.S. Steel from fans and pundits sneering at pinstriped domination. The typical Stadium crowd was considered dignified and upscale, in stark contrast to the more rabid fanatics populating the nearby Polo Grounds and Brooklyn’s Ebbets Field. Fans were not allowed to bring in signs, banners or noisemakers; that would have offended the “boxholders from Westchester,” as Yankee general manager George Weiss often referred to the more elite among the Stadium fan base. Spectators would be allowed to exit the Stadium by short-cutting through the field—and for the most part, they did so calmly and orderly. Even reporters were given first-class treatment; they had their own bar and lounge, and by 1950 not only found a more spacious press box hanging from the second (mezzanine) level to operate from, but they even had their own locker room with showers, and a room to write their stories.

To bulk up the Yankee bank account, Webb/Topping decided in 1953 to sell the Stadium to Chicago banker Arnold Johnson for $4.8 million; Johnson, in turn sold the land (but not the building) for $2.8 million to the Knights of Columbus, who then leased it back to the Yankees. Then it got really interesting; when Johnson purchased the A’s a year later and moved the team from Philadelphia to Kansas City, the American League ordered him to totally divest of the Stadium to avoid a potential conflict of interest. In something of a gentleman’s agreement, Johnson obliged by selling the Stadium to a meat-packing friend named John Cox—but they never signed a formal agreement to that effect, leaving suspicion that Johnson could have continued to make decisions behind the scenes without any potential legal wrist-slapping. It only fueled the conspiracy theory that Johnson’s Kansas City A’s were nothing more than an unofficial farm club for the Yankees, consummating a number of trades that always seemed to benefit the New Yorkers. The Stadium ownership saga took a unique (but more legally binding) turn in 1962 when Cox sold the facility to Rice University, for which he was an alum. So there it was, light years from Jacob Ruppert’s day: A Texas school owned Yankee Stadium.

Home Alone.

In the two decades following World War II, Yankee Stadium became the subject of constant rumor regarding additional tenancy. Every time the Yankees and Dodgers hooked up in the World Series—which was quite often during this period—there was talk that the entire series should be played at the Stadium since more profit could be made there than at Ebbets Field, a ballpark with little more than half the capacity; Dodgers management and fans alike saw the suggestion as an insult. Meanwhile, the New York Giants—who inadvertently helped create the Stadium by kicking out the Yankees 30 years earlier—ironically became the subject of a possible relocation to the Yankees’ home among other potential sites, but the teams never held any substantial talks on the subject. Thus the Giants, frustrated with New York City’s options, left for California—joining the Dodgers, who vacated Brooklyn for Los Angeles. By the time expansion became a baseball buzzword in the early 1960s, the Yankees had tired of the co-sharing idea, telling outside officials that it would not allow the newborn Mets to use the Stadium while Shea Stadium was being erected. (The Mets ended up playing their first two years at the Polo Grounds.)

In the four years following the departure of the Giants and Dodgers, the Yankees had New York City all to themselves. Attendance for all three teams had trended downward throughout the 1950s, so it was naturally assumed that the Yankees would get a bump at the gate by being the only ballgame in town. But in 1958, the Yankees’ first as a Gotham baseball monopoly, Stadium attendance actually dipped slightly—all despite another world title, won against Hank Aaron’s Milwaukee Braves. Trying to score converts from the Polo Grounds and Brooklyn proved futile, since Giants and Dodgers fans had built up so much hatred of the Yankees.

Those who did show up increasingly rooted for opponents, while the corporate fan element in general started to deteriorate. In 1961, Detroit slugger Rocky Colavito lived up to his name in a different way when he charged into the stands behind the dugout to confront a drunk Yankee fan taunting his wife and father; four months later, two teenagers jumped onto the field and attacked Cleveland’s Jimmy Piersall of Fear Strikes Out fame; Piersall punched one of the kids to the ground and kicked the rear of the other, retreating away. Even Yankee players weren’t spared; in 1960, New York megastar Mickey Mantle had to fight off unusually raucous fans swarming onto the field at the end of a doubleheader. The pummeling he took, intentional or otherwise, led to a hospital visit where he thought he’d broken his jaw.

By this time, the blue-eyed, blonde-haired Mantle had clearly established himself as the latest in a continuous line of Yankee legends, a switch-hitting wonder who had the ability to do just about anything. That he would last 18 years in the majors despite all the injuries and hard drinking was a wonder in itself.

Just as impressively, Mantle almost did the impossible: Hit a ball completely out of Yankee Stadium. Twice.

In 1956 off of Washington’s Pedro Ramos, and in 1963 off the Kansas City A’s Bill Fischer, Mantle smoked baseballs that hit off the copper frieze at the top of the upper deck in right field; another couple of feet higher, and both balls would have gone soaring out of the Stadium. Witnesses on both occasions said the ball was still rising when it struck the façade; using that assumption, it’s not unreasonable to assume each ball would have traveled close to 600 feet.

Mantle’s two shots were among the closest to depart the Stadium. In the early 1930s, the A’s Jimmie Foxx belched a Lefty Gomez pitch that landed two rows from the top of the last section of the upper deck behind left field; and in 1934, some claimed that Negro League legend Josh Gibson did smash a ball over the left-field bleachers and completely out of the Stadium, but reported eyewitnesses from the day contradict the oft-told tale.

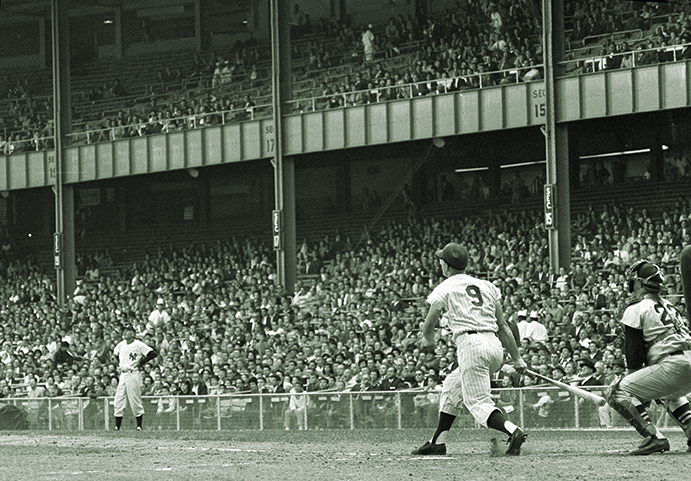

Roger Maris belts his record-breaking 61st home run before 23,000 at Yankee Stadium on October 1, 1961. Maris had been traded to New York by the Kansas City Athletics, owned by Arnold Johnson—who briefly also owned the Stadium in the early 1950s. (Associated Press)

Start Spreading the Boos.

Late in the 1964 season, CBS—television’s gold standard—bought the Yankees just in time to watch them win another pennant. It wouldn’t experience another under their decade-long rule over the franchise, which they unloaded to George Steinbrenner at a loss—an almost impossible thing to do in baseball. Before the network’s purchase, the Stadium had continued to be fine-tuned, sometimes for the better and sometimes not—such as the bastardization of the elegant front entrance, with its stately nameplate buried under a tacky electronic Longines clock, itself under a new ID atop the stadium spelled out in giant, spaced-out letters that glowed in neon red at night.

The network of Lucy, Gilligan and Ed Sullivan figured it would know how to put on a show at Yankee Stadium. In 1967, it underwent a $1 million-plus update to the Stadium, repainting much of the structure white and the green seats blue, modernizing the bathrooms, and installing an interactive “telephonic” Hall of Fame within the concourse where fans could pick up any one of 32 phones and listen to past Yankee greats talk about historic times, accompanied by poster-sized pictures and information. Female greeters, described by The Sporting News as “pretty young things CBS has hired to put a little sex into things,” helped guide fans to their seats. To show off these improvements, the Yankees held an Open House at the Stadium during a winter weekend to allow fans to check it all out and even meet the players. It served as the forerunner to the familiar ‘fan fests’ most teams employ today before spring training.

Not everything CBS did to improve the Stadium experience worked. In between games of a 1965 doubleheader, it put out a rock band, surrounded by go-go dancers. They were all booed off the field.

Worse, the Yankees themselves suffered under CBS. The team aged badly. No new blood came to the rescue, and there was no new icon around to replace Mantle and extend the chain of legends. The team struggled to reach .500, and although it managed to keep drawing over a million fans every season, over in Queens the expansion Mets—a perennial 100-game loser—were bringing more people into Shea Stadium. On one day in 1966, when a pitifully small crowd of 413 showed up—the smallest in Stadium history—veteran Yankee TV broadcaster Red Barber directed the cameramen to pan across the sea of empty seats; the front office was not amused and fired him.

The House That Lindsay Rebuilt.

The aesthetic upgrades applied by CBS to the Stadium proved to be relatively weak resistance to two bigger problems: The aging structure and the surrounding environment. The Stadium’s concrete began to show cracks, and fans didn’t help by using Bat Day, a Yankee tradition started in the early 1960s, to pound away at the structure. Outside, spectators were increasingly nervous of entering and exiting the Stadium amid a decaying neighborhood increasingly beset by gangs, graffiti and crime.

Many believe that George Steinbrenner was the primary force behind the effort to rebuild Yankee Stadium in the mid-1970s, but he was nothing more than a mere benefactor. The seed for the massive makeover was actually planted in the Summer of 1970 by New York mayor John Lindsay, who in an unusual twist to the typical “team unhappy, team wants new stadium” template was the one to initiate the conversation about reviving the Stadium. He had two good reasons; one was the memory of the Giants and Dodgers leaving town, the other noise made across the Hudson by New Jersey interests envisioning a multi-sports complex in the Meadowlands—and the likelihood that they would try to poach as many New York teams, the Yankees included, as possible.

Yankees president Mike Burke, more than happy to take up the discussion with Lindsay, gave his wish list of objectives: Improving not only the Stadium, but also parking, traffic and the surrounding area. Burke caught on to the New Jersey chatter and kindly reminded Lindsay that a move there could be an option if nothing was done.

Lindsay took charge. In 1971, he used eminent domain to acquire the Stadium for $2.5 million and set aside $21.5 million in additional budget to overhaul the venue. On paper, the project would be as ambiguous as it was ambitious. The budget number was basically grabbed out of the air; even the city’s Board of Estimate admitted to the New York Times that it would upgrade the Stadium, “whatever the cost.” It was hardly the reassuring note New York’s citizens, helplessly watching their city hurtle toward bankruptcy, wanted to hear. Their suspicions would be justified when the final project bill came in at a whopping $100 million—half for the Stadium reno and the other half for outside improvements.

The Yankees played two seasons at Shea Stadium while reconstruction took place. The structural core of the original building remained, but it was accommodated by major fixes. The upper two levels became cantilevered, allowing for the removal of the obstructive posts. The wooden seats were replaced with wider, bright blue plastic ones—reducing capacity to 54,000. Escalators were installed for upper deck fans. The field dimensions were reduced, though Death Valley remained a still-menacing 430 feet away; by 1988, it would be shortened further to 399. The monuments and flagpole were taken out of play, moved to a patio-like area in between the bullpens and in front of the bleachers. Outside, 6,000 new parking spaces were added with direct access to the Stadium—allaying fans’ fears of treading through the rundown neighborhood. A series of oval-shaped, three-story office structures were annexed to the exterior and, adding kitsch, a 138-foot-tall smokestack shaped as a baseball bat standing upside-down was placed in the entry plaza.

Most unforgiving, the Yankees demoted the iconic drape-like frieze from the top of the third deck, replacing it with a ring of lights; the frieze reappeared in plastic form, gracing a tall wall behind the bleachers that mixed scoreboards and ads.

There was no debating that the “new old” Yankee Stadium looked more modern. But sapped of much of its classic appeal, it also looked more sterile.

The Bronx Zoo.

Fittingly, the ceremonial first pitch at the rebuilt Stadium, on April 15, 1976, was thrown by Bob Shawkey, who started the first game at the original venue back in 1923. Echoing that initial campaign, the 1976 Yankees won the AL pennant—then, in each of the following two years, won their first two World Series since the early 1960s. The fans returned, as a minimum of two million turnstiles were clicked in each of the first five years back at the Stadium. And they were as nutty as ever; they threw everything from fruit to golf balls onto the field, launched Roman candles from the upper deck, and made it a raucous tradition to storm the field whenever the Yankees clinched anything. Chris Chambliss most memorably felt the pain of victory when he launched the pennant-winning homer against Kansas City in 1976; his ensuing trot around the bases wasn’t so much a walk-off as it was survival, bruising his way past scores of crazed, happily violent fans on his way to home plate—which, by the way, he never touched. By 1987, the Yankees finally provided sanctuary for the more G-rated portion of the fan base by creating a family section that would be free of alcohol and (hopefully) verbal abuse.

Chris Chambliss’ struggle to complete his pennant-winning home run in 1976 was the epitome of raucous fan behavior at the Stadium following its reconstruction. (Associated Press)

As unruly as the fans remained, they had nothing on the Yankees themselves. George Steinbrenner’s authoritatively brash, tabloid-soaked rule of the team gave the witty writers at the New York Post and New York Daily News a goldmine of headline fodder for years to come. Adding to the fuel was brilliant but highly combative manager (and former 1950s Yankee infielder) Billy Martin—who Steinbrenner hired and fired five times—and flamboyant slugger Reggie Jackson, who ate up the lively New York spotlight while constantly sparring, sometimes physically, with Martin. At a time when disco, drugs, and Saturday Night Live provided the mold for a bankrupt city living on the edge, the Yankees and their refurbished Stadium seemed to fit right in.

With a personality that would draw strong comparisons down the line to Donald Trump—without the knack for bankruptcy—Steinbrenner was always difficult to be taken at his word. He impulsively fired managers and coaches, berated his players in public, and was twice given long suspensions by baseball for various illegalities; heavens know how much worse he would have been had Twitter been around for him to master. When Steinbrenner wasn’t busy bitching about his team, he found time to bitch about the Stadium, even in its renewed state. He complained that not enough parking spaces were implemented, wanted to tear up leases, and fumed over attendance, alternately bashing the fans and city. In July 1993, he held a “test week” to see if enough fans would show up for a seven-game homestand; the average crowd of 32,000 wasn’t enough to shut “The Boss” up and keep him from publicly ranting about moving into Manhattan or, once again, New Jersey.

In 1998, Steinbrenner lucked into a legit opportunity to complain about the state of the 75-year-old Stadium. Hours before a scheduled April game against the Anaheim Angels, a 500-pound expansion joint broke loose from the upper deck and fell below, knocking out a seat in the mezzanine and creating a small hole for which one could peak down to the field level. The game—and two others to follow—were postponed as contractors made sure that the Stadium wasn’t literally falling apart. The word was given that all was safe, but Steinbrenner had found his smoking gun. He would spend the next seven years diligently seeking a new ballpark for the Yankees.

For all his intolerant warts, Steinbrenner knew how to build a winner. He restored greatness to the Yankees after CBS’ decade-long wayward drift, making the postseason 17 times in the Stadium’s final 33 seasons—six of those ending with the Yankees hoisting the World Series trophy. Steinbrenner made for early success by mastering the fledgling free agency system in the 1970s; after a star-studded drought in the 1980s in which he gave away top prospects for over-the-hill former All-Stars, he learned his lesson in the 1990s by nurturing—and keeping—an impressive new wave of youngsters that yielded Hall of Famers in shortstop Derek Jeter and closer Mariano Rivera, among many others, while also keeping his mouth shut and letting manager Joe Torre do his job. That led to three straight championships from 1996-98. Businesswise, Steinbrenner also transformed the Yankees into one of the world’s most lucrative sporting enterprises, thanks in part to his formation of the YES regional sports network.

The mellow Steinbrenner of later years, which beget a well-bonded winning roster, reaped major dividends at the Stadium box office. In 1999, the Yankees drew three million fans for the first time; six years later, they topped four million. By 2008, their final season at the Stadium, they topped all previous team records by attracting an AL-record 4,298,655—practically a sellout for every game, and a number Jacob Ruppert likely never comprehended.

After the rebuild: The monuments are placed behind fences brought in to reduce Death Valley’s size, and the frieze façade (remade using plastic) is relocated from the upper deck to behind the bleachers. (Flickr—Chris Murphy)

After saying no to one proposal after another, George Steinbrenner finally said yes in 2005 to a new Stadium, to be completed right next to the old one in 2009. While there was a sense that the adjacent new yard would represent more of a transition than a departure, it didn’t make those who’d miss the old yard any more content. “You can take Yankee history across the street,” Stadium tour operator Tony Morante told Sports Illustrated, “but you can’t take Yankee Stadium across the street.”

The final game, and the ceremonies that preceded it, was shown before a nationally televised Sunday evening audience on September 21, 2008. All the legends were rounded up for one last visit, including Yogi Berra, Whitey Ford, Don Larsen, Graig Nettles and Reggie Jackson; Julia Ruth Stevens, the 92-year-old daughter of Babe Ruth, bounced the ceremonial first pitch. The Yankees, as they did 63% of the time at the Stadium, won—breaking open an early tight affair with the Baltimore Orioles and triumphing, 7-3. Catcher Jose Molina provided the other bookend to the initial one created by Babe Ruth and hit the Stadium’s 11,270th and last homer. Mariano Rivera sealed the deal with a 1-2-3 inning in the ninth; he didn’t get credit for a save, but who else was going to finish it up?

The Yankees would have been remiss to gloss over a few other long-time Yankee legends of a different kind who worked at the Stadium day in and day out for long stretches. The Yankee clubhouse was named after Pete Sheehy, who as a 12-year old in 1927 was literally picked out of a crowd to help out in the locker room; he eventually assumed the head job and worked until his death in 1985, dutifully seeing after all the players and their equipment. There was Eddie Layton, who played the Stadium organ from 1967-2003 after providing background organ work for CBS soap operas. And last and far from least, there was Bob Sheppard, who began work as the Stadium’s public address announcer in 1951—Joe DiMaggio’s final year as a Yankee—and continued through 2007 and the heyday of Derek Jeter and Alex Rodriguez. At age 97, Sheppard became too ill to work the Yankees’ last year at the Stadium—but provided a tape recording of the lineup for the final game. At the new Stadium, Jeter insisted that as long as he played for the Yankees, he wanted to come to bat with a recording of Sheppard announcing him.

The old Stadium was gradually disassembled, and the property became a new home for Macombs Dam Park, an outdoor recreational area that had previously been located to the north of the Stadium before parking for the new Stadium replaced it. A large chunk of the park consists of Heritage Park, a collection of three baseball diamonds of various sizes with a shared outfield. Surrounding it are memories, some physical, of the old Stadium. A couple slices of the reconstructed frieze separates a walkway from one of the diamonds; the enlarged baseball bat-shaped smokestack remains standing at the other end of the park; and walkways include pavement stones listing great moments from the Stadium’s history.

The thrill of walking into old Yankee Stadium is gone. The new Stadium does well to retain the old’s architectural stylings, but it lacks the sheer grandeur of its predecessor. With a smaller capacity and playing field, it smacks more of a typical major league ballpark, and that’s probably fine with the Yankees. After all, intimacy is trending. Enormity isn’t.

But who knows—perhaps when a group of kids are playing a pick-up game at Heritage Park, they’ll get some whispers of advice from unseen ghosts of past Yankee legends who once called this land home.

And the kids should take it.

The Ballparks: Polo Grounds Peculiar doesn’t even begin to describe the Polo Grounds, a bathtub of a ballpark that yielded pop fly home runs and tape-measure outs as it led almost as many lives as a cat against the rocky bluffs of Harlem. Through its resiliency manifested more than its share of baseball’s legendary moments and unforgettable actors, whether it was McGraw, Mathewson, Merkle, Master Melvin, Mays or, yes, even Marvelous Marv.

The Ballparks: Polo Grounds Peculiar doesn’t even begin to describe the Polo Grounds, a bathtub of a ballpark that yielded pop fly home runs and tape-measure outs as it led almost as many lives as a cat against the rocky bluffs of Harlem. Through its resiliency manifested more than its share of baseball’s legendary moments and unforgettable actors, whether it was McGraw, Mathewson, Merkle, Master Melvin, Mays or, yes, even Marvelous Marv.

New York Yankees Team History A decade-by-decade history of the Yankees, the ballparks they’ve played in, and the four people who are on the franchise’s Mount Rushmore.