THE YEARLY READER

1911: The Legend of Home Run Baker

Stealing a major league-record 347 bases to get to the World Series, the New York Giants find their strategy trivialized by Frank Baker, whose two critical home runs propel the Philadelphia A’s to their second straight championship.

He was a man of unassuming character, unassuming size—and by today’s standards, unimpressive power numbers.

But Frank Baker of the Philadelphia A’s would awe the fans of his day with a slugging exhibition during the 1911 season—followed by his slugging heroism in the World Series.

In the six years previous to 1911, only two American League players, Harry Davis and Jake Stahl, had reached double figures in season home run totals—and they both barely made the grade. Welcome to the deadball era; the pitchers were in control, legally allowed to throw any kind of pitch in the book. They had the extra advantage of using the same ball in play for, sometimes, the entire game. If any hitter was fool enough to make a living smacking the lifeless, beat-up ball over the fence, the hideously long distances to the outfield walls would give him second thoughts.

Baker’s first two years in the majors bore numbers typical of a deadball era player, totaling six home runs while expansive outfields allowed him to leg out 34 triples. He made do like everyone else, hitting for average, stealing bases—generally making his way home one bag and one play at a time.

Carrying a heavy bat to make up for his modest 5’11”, 175-pound frame, Baker began showing more pop for the Athletics in 1911. It resulted with his leading the AL with 11 home runs—the most hit by any player in the junior circuit over the previous five years.

Yet it took a sensational and well-timed performance in the World Series against a noted New York Giants pitching staff for the public to forever anoint Baker a new, more popular version of his first name. From here on, Frank Baker would bow to Home Run Baker.

Baker was more than just a home run hitter for the Philadelphia A’s, and the A’s were more than just Baker. A year after becoming the first AL team to win 100 games, the A’s repeated the feat in 1911. Reaching triple figures, however, was no assurance that the A’s would snatch another pennant, thanks to a rampaging start by the Detroit Tigers—who won 21 of their first 23 and held first place well into July with a 59-24 record. But from there, the Tigers pitching staff collapsed, apparently unable to adapt to a livelier ball introduced that year in the AL. It doomed their hopes, and the A’s flew passed Detroit with such a flash that, by September, it wasn’t even a race anymore. Philadelphia loaded up a 13.5-game lead over the second-place Tigers at the finish for its second straight AL flag.

BTW: In winning only 30 of their remaining 71 games, the Tigers produced a 4.50 ERA which, by 1911 standards, was atrocious.

Veteran outfielder Danny Murphy (second from left) poses with the A’s young “$100,000 Infield”: Stuffy McInnis (far left), Frank “Home Run” Baker (center), Jack Barry (second from right) and Eddie Collins (far right). (The Rucker Archive)

The A’s, unlike Detroit, continued to get solid pitching from their veteran staff. Jack Coombs, a year after his fantastic 31-win campaign, saw his ERA jump from 1.30 to 3.53—yet he still found a way to win, leading the AL for the second straight year with 28 victories. Eddie Plank rebounded from a relatively mediocre 1910 offering to win 23 of 31 decisions with a team-best 2.10 ERA. Chief Bender went 17-5, giving him a superlative three-year mark of 58-18.

Offensively, manager Connie Mack’s lineup included a vastly talented group of young infielders—with the 25-year-old Baker as the elder statesman at third base. Eddie Collins tied Baker for the team lead with 38 steals and batted .365 to pace the A’s while placing fourth overall in the AL—a placement all the more noble given that the three men ahead of him were Ty Cobb, Joe Jackson and Sam Crawford.

Defensively, the infield was solid, with Baker and shortstop Jack Barry leading their positions in fielding average. The impressive makeup of this infield—Baker, Collins, Barry and 20-year-old first baseman Stuffy McInnis—gave rise to the nickname, “The $100,000 Infield,” named as such since it was considered the collective worth of the four players.

The Philadelphia outfield would have been of similar, if not greater, value had the A’s been able to keep young Joe Jackson, an illiterate who seemed to be fluent only at baseball. Jackson seldom got a chance to play at Philadelphia, liked neither his teammates nor the town, and was dealt to Cleveland for 1911—earning superstar status by hitting .408 in his first full season. But even with Shoeless Joe, the Naps’ hopes for a total breakthrough collapsed through hard luck and tragedy; Nap Lajoie missed half the season to abdominal problems, and future Hall-of-Fame pitcher Addie Joss shockingly died before the season began, a victim of tubercular meningitis at age 31. The Naps finished a distant third.

Over in the National League, the New York Giants didn’t quite catch fire out of the gate—until their ballpark did. On the night after the Giants lost their second home game of the year in as many tries, the Polo Grounds burned to the ground in a fiery blaze, a fire so bright that the glare could be seen all across New York City.

Cause unknown, the burning left the Giants homeless overnight. Manager John McGraw, who still showed little love for the American League and the New York Highlanders in particular, swallowed his pride in the face of the moment’s severity and accepted the invitation of his crosstown archrivals to share Hilltop Park while a new, steel-and-concrete Polo Grounds quickly rose from the former’s wooden ashes.

New York Giants players and officials survey the damage to the Polo Grounds a day after the wooden facility burned to the ground. The most persistent rumor as to how the fire started revolved around a fan discarding a cigarette below the wooden bleachers, where it ignited a newspaper. (Library of Congress)

The forced change of venue didn’t seem to affect the Giants’ performance through the spring, as they hung close to first place. They played like a team on the run, stealing bases left and right to the tune of a major league-record 347 in one year—a mark still unbroken. The Giants claimed six of the league’s top eight base stealers, and five stole over 40—led by Josh Devore’s 61.

BTW: While playing in their temporary home at Hilltop Park, the Giants won 21 of 29 games.

Getting runners on base to steal was no problem for New York, leading the NL with a .279 batting average. While second baseman Larry Doyle emerged as the Giants’ top hitter—leading the team with 13 home runs, 25 triples and 102 runs scored—22-year-old Fred Merkle developed into a serious threat by adding 12 homers and 84 runs batted in. Merkle’s impressive play, if anything else, was hoped to cement forgiveness from Giants fans for his famous bonehead play of three years earlier that cost the team a NL pennant.

Purchased from the minors for a record $11,000 by the Giants, Rube Marquard belatedly found success at the major league level in 1911 after struggling through his first few years. (The Rucker Archive)

On the mound, the Giants received a boost from 21-year-old left-hander Rube Marquard, who had been the center of attention three years earlier when the Giants purchased him from the minors for $11,000—at the time, the largest sum ever paid to obtain a minor leaguer. Through Marquard’s first three years in New York, many wondered aloud why so much had been paid for what little the Giants got in return: A combined 9-18 record. In 1911, Marquard suddenly silenced the naysayers. Blessed with an electrifying fastball, he achieved a 24-7 record and led the league in winning percentage (.774) and strikeouts (237).

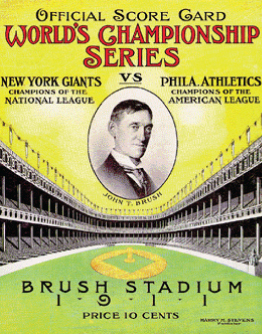

The new and improved Polo Grounds, officially named Brush Stadium after ailing Giants owner John Brush (he would die late in 1912), opened at the end of July. By then the Giants were closing in on first place—their young stars solidifying, the team momentum surging.

The Giants passed up the reigning NL champion Chicago Cubs to take first place in late August and accelerated from there, attaching an exclamation point to the pennant drive by winning 30 of 36 games down the stretch to finish one victory short of 100 for the season.

Misfortunes of health doomed the Giants’ trailers in the standings. The famed Tinker-to-Evers-to-Chance combination that had elevated the Cubs’ success for so many years completely came apart; Johnny Evers suffered a mental breakdown and played little, manager Frank Chance was forced to end his playing days from a blood clot to the brain brought on by too many beanings, and Tinker was repeatedly admonished by Chance for play so lackadaisical that it led to suspension. In Pittsburgh, the Pirates’ momentum was curtailed late in the year when Honus Wagner missed a month of action. And finally in Philadelphia, the surprising Phillies—who had reached the NL’s top spot in July, thanks to rookie 28-game winner Pete Alexander—fell apart after catcher-manager Red Dooin, batting .328, broke his leg. He could only watch as his team ultimately slipped to fourth.

In a rematch of the 1905 World Series pitched to near perfection by the Giants, the Philadelphia A’s must have felt a case of déjà vu coming on as Christy Mathewson nailed them down once more in Game One, 2-1. In winning, however, the great Mathewson finally showed a mortal side in the Fall Classic, allowing his first career earned run after 28 shutout innings of Series competition.

For Game Two, the true hero of the 1911 Series would make his presence known.

Frank Baker stepped up to the plate in the sixth inning, facing Rube Marquard in what had been a well-pitched duel with the Athletics’ Eddie Plank. But Baker blasted a two-run shot to right field that broke up a 1-1 tie, and with no more scoring gave the A’s a 3-1 victory before the Shibe Park home crowd.

Mathewson, in a ghostwritten, personal column for one of the local New York papers, slammed the young Marquard the next morning for giving up the home run to Baker. He wrote too soon.

A program for the 1911 World Series trumpets the return of the rebuilt Polo Grounds, which was officially named Brush Stadium after Giants owner John Brush.

And it was Baker who homered to tie it.

Adding insult to injury, Baker singled and scored the eventual game-winning tally during an 11th inning rally, securing a 3-2 victory to give Philadelphia the edge in the Series.

Marquard, who had his own ghostwritten column, didn’t waste the opportunity to return the harsh criticism in kind to Mathewson.

Only one player (Fred Clarke, the year before) had hit as many as two home runs in a single World Series, and now Baker had done it through just the first three games—both at crucial moments. The press ate it up while the Series stalled due to a week of rain; Frank Baker was reborn in the public eye as Home Run Baker.

Though Baker would not slam any more homers once the Series recommenced, he remained dangerous enough to Giants pitching. In Game Four, his two doubles contributed to a 4-2 beating of the Giants and Mathewson.

Down three games to one, the Giants stayed alive in New York by winning Game Five—but not without controversy. Bouncing back from an early 3-0 deficit, the Giants pulled even with two runs in the ninth, then won it in the 10th when Larry Doyle scored on a sacrifice fly. However, umpire Bill Klem never signaled Doyle safe; Klem later would say Doyle didn’t touch the bag, and the A’s never realized it. Had they watched along with Klem and made a tag of the plate, the game would have remained tied and, just three years after the Merkle Boner, the incident might have resulted in a second, more deliberate burning of the Polo Grounds within the year.

Not paying attention to home plate did no more damage to the A’s than to allow them to clinch their second straight World Series title at home, thrashing the Giants, 13-2, in Game Six at Shibe.

Philadelphia pitching was consistently brilliant throughout the Series, using just three hurlers (Jack Coombs, Chief Bender and Plank), all of which sported ERAs under 2.00. But it also didn’t help the Giants—with their record 347 steals during the season—that they were successful in only three of 12 stolen base attempts in the Series.

The big story, however, was Home Run Baker. He led the Series with a .375 average, seven runs, four extra base hits—and of course, two home runs.

Forward to 1912: The $30,000 Muffs A series of critical blunders do in the New York Giants against the Boston Red Sox at the World Series.

Forward to 1912: The $30,000 Muffs A series of critical blunders do in the New York Giants against the Boston Red Sox at the World Series.

Back to 1910: A Carload of Trouble The World Series becomes anticlimactic following a strange and controversial ending to the individual batting race between two of baseball’s premier hitters: Nap Lajoie and Ty Cobb.

Back to 1910: A Carload of Trouble The World Series becomes anticlimactic following a strange and controversial ending to the individual batting race between two of baseball’s premier hitters: Nap Lajoie and Ty Cobb.

1911 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1911 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1911 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1911 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1910s: The Feds, the Fight and the Fix The majors suffer growing pains as they deal with a fledgling third league, increased scandal and gambling problems, and a brief interruption from the Great War.

The 1910s: The Feds, the Fight and the Fix The majors suffer growing pains as they deal with a fledgling third league, increased scandal and gambling problems, and a brief interruption from the Great War.