THE YEARLY READER

1912: The $30,000 Muffs

A spate of critical defensive blunders doom the New York Giants in a seven-game World Series showdown with the Boston Red Sox, playing their first season at historic Fenway Park.

(Library of Congress)

Fred Merkle thought he had achieved the ultimate atonement.

The 23-year-old first baseman, who four years earlier committed a nightmarish baserunning blunder that cost the New York Giants the 1908 National League pennant, had just delivered in Game Seven of the 1912 World Series with a go-ahead, run-scoring single in the top of the 10th inning.

But the Giants, who seemed to specialize in blowing big games in the most embarrassing of ways, lost the lead, the game and the Series with a comedy of errors that gave the upstart Boston Red Sox their second-ever world championship.

For the Giants, it was their second straight Series defeat. For Merkle, his chance to provide a heroic moment and even the score with history was reduced to a footnote in a different, more memorable finish.

A young yet experienced ballclub, the Giants made little roster moves before 1912 and squashed all other takers in the NL by jumping out to one of the best starts in major league history before coasting to a 10-game finish over second-place Pittsburgh.

Merkle and Larry Doyle continued to provide the power, each collecting 10 or more home runs for the second straight year. Everybody chipped in on the basepaths, as the Giants continued to rack up a multitude of stolen bases—319 in all, not far below their record output of 347 a year earlier.

The Giants’ pitching staff deepened with the addition of 225-pound rookie spitballer Jeff Tesreau, who confounded opponents with a league-best 1.96 earned run average. Christy Mathewson continued to be Christy Mathewson, notching another 23 wins. And Rube Marquard picked up where he left off from 1911—and then some. Marquard opened the season with 19 victories without a loss, setting a record for consecutive wins in a season that still stands; he also set a mark of 21 straight triumphs overlapping two years, a record later broken by future Giants great Carl Hubbell.

As a team, the Giants put together a 16-game win streak into early July that capped off a stunning 54-11 start to the season, giving them a 16.5-game lead to serve notice to the rest of the NL that it was time to fold up shop before midseason.

Not to be outdone, the American League put in its share of memorable streaks. Walter Johnson laid claim as the junior circuit’s premier ace, the hard-throwing Washington Senator collecting 32 wins (against 12 losses) to go with a league-best 309 strikeouts and 1.39 ERA. Not lost within all the numbers was his own winning streak, a 16-game string, which ended in a rare relief appearance when he entered a tie game and gave up the deciding run.

Looking for Number 17

By establishing an AL mark with 16 consecutive wins in one year, both Walter Johnson and Smoky Joe Wood set the standard that would occasionally be equaled—but frustratingly never surpassed. Two National Leaguers, Rube Marquard—also in 1912—and the Pirates’ Roy Face in 1959, would win 19 and 17 straight in one year, respectively; Roger Clemens (20 wins), Johnny Allen and Dave McNally (17 each) would build up longer streaks, but over two seasons.

Johnson’s streaky success inspired his team to win 17 straight early in the season to catapult Washington into a rare state of contention. But while the Senators sprinted towards first place, another team grabbed it—and never relinquished it.

The Boston Red Sox were led by player-manager Jake Stahl—at 32, the oldest player on the team and the youngest manager in the majors. The rest of the Red Sox players had youth written all over them, and though the team wasn’t the youngest in baseball, their sudden rise to the top of the AL stunned many who expected less from a squad that had labored around the .500 mark for years.

The driving force in the Boston lineup was center fielder Tris Speaker, who at 24 secured superstar status. There was little Speaker couldn’t do; he hit for average (.383, trailing only Ty Cobb and Joe Jackson), hit for power (his 10 home runs tied him for the league lead with, naturally, Home Run Baker), stole 52 bases and played impeccable defense in the outfield.

Though rated the league’s best pitching staff the year before, the Red Sox had room to improve in 1912—and improve they did. Leading the effort for the Sox was a breakout pitcher who was performing on a level with—and at times surpassing—Walter Johnson.

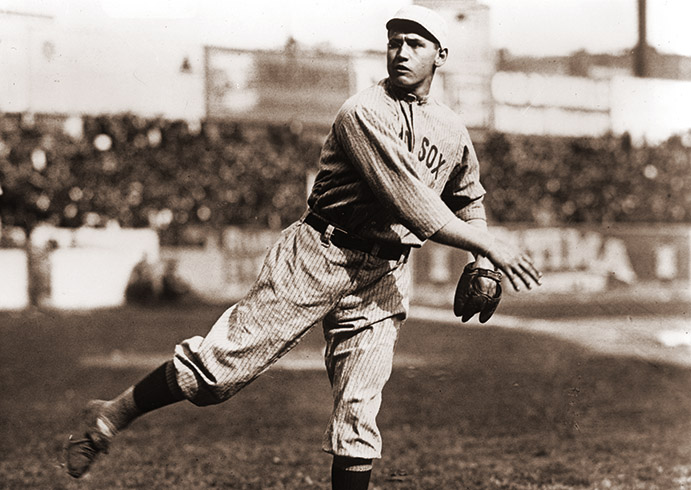

Smoky Joe Wood had made a slow, steady rise to the role of staff ace, but in 1912 he suddenly cranked it up. Nicknamed for his fastball, Smoky Joe lived up to that image by recording an astounding 34-5 record—tops in the majors—while his 258 strikeouts were second only to Johnson.

At age 22, Smoky Joe Wood briefly rose to fame as baseball’s most dominant pitcher, before his blazing fastball and punishing over-the-shoulder delivery led to a quick burnout on the mound. Wood salvaged his major league career by evolving into a good-hitting, part-time outfielder for the Cleveland Indians into the 1920s. (The Rucker Archive)

As Johnson reeled off his 16-game win streak, Wood started one of his own. The two squared off in a memorable matchup on September 6, with Johnson’s streak over—and Wood looking for his 14th straight. Wood prevailed 1-0 as Johnson, after watching him from the dugout, paid the right-hander the ultimate compliment: “No man alive can throw harder than Smoky Joe Wood.” Wood’s string would also end at 16, and with Johnson he set the standard for future American Leaguers who would equal—but never better—the mark.

A new ballpark for the Red Sox in 1912 further motivated the team. Straddled along Brookline Avenue near downtown Boston and built for less than a half million dollars, Fenway Park opened its gates for the first time. Remarkably, in spite of the new surroundings and the Sox’ vastly improved performance—resulting in the club’s best-ever season record—attendance improved only marginally, from 500,000 to 600,000.

The ensuing World Series between the Red Sox and Giants quickly demonstrated that it would go to the wire. After Wood triumphed in Game One, a lively Game Two at Fenway saw an 11-inning, 6-6 deadlock halted by darkness, ending in a draw and wasting a complete game performance by Christy Mathewson—who was not helped by five Giants errors. The Giants won a “replayed” Game Two the next day; a 2-1 lead was secure in the bottom of the ninth when, with two runners in scoring position and two outs, Forrest Cady’s screaming liner into center field was snagged by the Giants’ Josh Devore. The moment was so obscured by descending darkness and fog, many fans who had lost sight of the fly ball were sure it wasn’t going to be caught, and walked to the exits convinced the Red Sox had won the game.

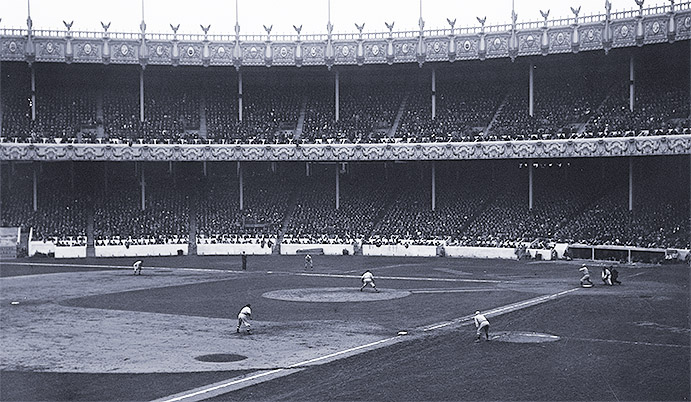

The Giants’ Jeff Tesreau faces off against the Boston Red Sox in game Four of the 1912 World Series at New York’s Polo Grounds. The Red Sox would win, 3-1, giving Smoky Joe Wood one of his three Series wins. (Library of Congress)

Behind Wood and 20-game winner Hugh Bedient, the Red Sox won Games Three and Four, turning the pressure up on New York. But the Giants fought back to tie the series for a seventh game, beating up on Red Sox starter Buck O’Brien in Game Five, 5-2, then finally getting to Wood with an 11-4 thrashing in Game Six.

BTW: Game Six featured an unassisted double play by outfielder Tris Speaker, who had a historical knack for pulling off such plays; it’s the only such event ever recorded by an outfielder in Series history.

With an eighth World Series game—including the discounted tie—not originally scheduled, a coin flip determined the home site: Fenway Park.

It would be one of the wildest finales in Series history.

With Mathewson and Bedient dueling, the two teams squared off evenly for nine innings. Tied at 1-1, extra innings became reality, and the Giants and Fred Merkle quickly tallied in the 10th off Wood—who had replaced Bedient in the eighth.

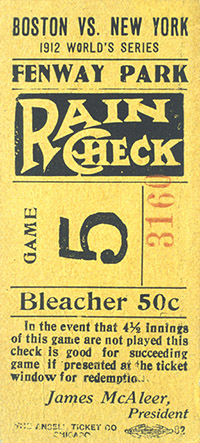

A ticket stub for Game Five of the 1912 World Series at Fenway Park during its first year of operation. (The Rucker Archive)

With Engle reaching second on the error, Harry Hooper next lashed a drive in the direction of Snodgrass—who quickly made up for his muff with a terrific diving catch. Yet Engle, the tying run, moved to third on the play.

After Steve Yerkes walked, to the plate approached Tris Speaker. Mathewson got him to pop one up in foul territory near Merkle at first base. Merkle, Mathewson and catcher Chief Meyers all converged, and out of the air came the words, “Take it Chief, you take it!”—even though Meyers had the worst angle on the play. The words were actually those of Speaker, running down the line; Merkle and Mathewson froze while Meyers couldn’t catch up to the pop, which landed untouched.

Giving himself new life at the plate, Speaker promptly wrapped a single to score Engle and tie the game, while sending Yerkes to third as the potential game winner. Two batters later, Larry Gardner ended the horror show for the Giants by launching a deep fly to right which was caught by Josh Devore—but too far away from home plate to gun down Yerkes, who completed the sacrifice fly and scored the Series-winning run.

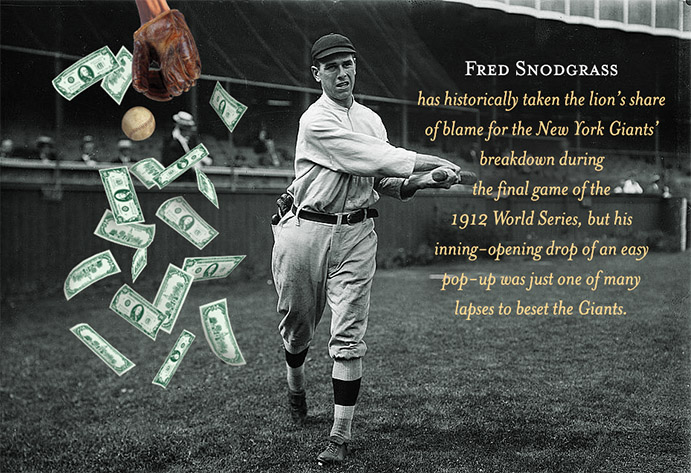

Snodgrass, for starting things off on the wrong foot defensively for New York, took the brunt of the criticism. Though many would focus on Snodgrass and his “$30,000 Muff”—because it was the difference in the amount of money given to the winning and losing teams of the Series—there was plenty of blame to be shared among the Giants, who as a team committed 17 Series errors. Mathewson, despite allowing just four earned runs over 28 innings, was tagged with eight additional unearned runs and won none of his three starts, stretching his World Series winless streak to five games.

FYI: Neither the Giants nor Red Sox were defensively deft during the World Series, ganging up to accumulate 31 errors.

So Brilliant, and Yet so Brief

Buck O’Brien and Hugh Bedient each won 20 games for the Red Sox in 1912, yet combined to win just 32 more for the rest of their careers. Below is a list, topped by O’Brien and including Bedient, of major league pitchers (not including those currently playing) with the fewest victories over a career that included a 20-win season.

For all the controversy swirling in the Fenway winds during the World Series, it didn’t top the earlier episode of infamy ignited at New York’s Hilltop Park in May. At the center of the storm: Ty Cobb.

A spectator had viciously heckled Cobb during batting practice and into a contest between the Tigers and Highlanders. Cobb, who normally displayed violent kneejerk reactions to such taunting, bit his tongue for a long while, but when the heckler called Cobb a “half-nigger,” the Southern-born Detroit superstar—the subject of many racist-tinged incidents—finally exploded.

Bursting into the stands, Cobb found the man and started administering one of his wild trademark beatings. He slowly realized that the heckler, whose name was Claude Lueker, was handicapped; Lueker had lost eight fingers in an industrial accident. When horrified onlookers pleaded with Cobb that the man had no hands, Cobb was heard to scream back, “I don’t care if he has no feet.”

Cobb was immediately ejected by umpire Silk O’Loughlin—and later indefinitely suspended by AL President Ban Johnson. In a major surprise, the other Tigers players—who by and large were no friends of Cobb, yet understood his position—uncharacteristically backed him, saying they would boycott until Cobb was allowed back on the field.

Detroit’s next scheduled game was at Philadelphia—and Johnson warned Tigers owner Frank Navin that he would be fined $5,000 for each game in which he could not field a team. With Cobb suspended and his teammates striking in protest, Navin acted fast. He rallied up a host of amateur and semipro players from the Philadelphia area to perform as Detroit Tigers, paying most of them $10 a game. A 20-year-old Jesuit priest named Al Travers was offered $25 to start—and another $25 to finish. Travers collected and took the beating of a major leaguer’s life; in losing 24-2, he gave up every A’s run and every one of their 26 hits. For that he ingrained himself into the record books for the most hits and runs allowed by a pitcher in one game, ever. Some in the crowd of 15,000 were amused, others angered at having to pay premium prices for such a one-sided exhibition.

Tiger players remained defiant, even after Johnson came directly to them and warned they would be banned for life if they continued their boycott. In the end, it was Cobb who played the peacemaker, urging his teammates to get back on the field.

The final tally for the whole affair: A 10-day suspension and a $50 fine for Cobb; no suspensions for his teammates, but a $100 fine each (all covered by Navin); a beat-up handicapped heckler, who later claimed he was mistaken for someone else; one big fat victory for the Philadelphia A’s; and a whole bunch of guys who got to taste life in the bigs for at least one day.

BTW: There was a short-lived legacy to the Cobb controversy: A player’s union. Established to give major leaguers more leverage in player-related issues, the Player’s Fraternity became another in a string of unsuccessful attempts at organized baseball labor. It fizzled out by 1915.

Forward to 1913: Giant Bridesmaids, Again Not even good luck charm Charlie “Victory” Faust can save the New York Giants from another World Series defeat.

Forward to 1913: Giant Bridesmaids, Again Not even good luck charm Charlie “Victory” Faust can save the New York Giants from another World Series defeat.

Back to 1911: The Legend of Home Run Baker Frank Baker famously powers the Philadelphia Athletics past an aggressive New York Giants squad in the World Series.

Back to 1911: The Legend of Home Run Baker Frank Baker famously powers the Philadelphia Athletics past an aggressive New York Giants squad in the World Series.

1912 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1912 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1912 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1912 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1910s: The Feds, the Fight and the Fix The majors suffer growing pains as they deal with a fledgling third league, increased scandal and gambling problems, and a brief interruption from the Great War.

The 1910s: The Feds, the Fight and the Fix The majors suffer growing pains as they deal with a fledgling third league, increased scandal and gambling problems, and a brief interruption from the Great War.