THE YEARLY READER

1918: All Work or Fight and No Play

As the Great War wears a terrible toll, the U.S. Government presses baseball to do more than its fair share in contributing to the war effort; after a threatened shutdown, the game is allowed to play on and the Boston Red Sox win their last World Series for 86 years.

Emulating U.S. military servicemen, the Washington Senators march in step before a game. Such patriotism didn’t go far enough in the eyes of the U.S. Government, which felt that major league owners and players weren’t sacrificing enough to the war effort. (The Rucker Archive)

The United States of America had been at war for a year, and its citizens were beginning to wonder if baseball was getting its priorities straight.

A single gunshot had assassinated the Archduke of Austria-Hungary four years earlier, igniting the Great War and plunging Europe into total armed conflict. America had remained neutral on the other side of the Atlantic, but when German U-boats began to indiscriminately strike at ships with Americans on it, the U.S. declared war on Germany—just days before baseball began its 1917 campaign.

While most minor leagues closed up shop, the majors went forward with their full schedule for 1917. Only a handful of players had been drafted into the military; fewer enlisted. Those who continued to play took part in token military “drills” to show their support for the boys overseas. Owners donated fair amounts of cash to the war effort, and rounded up baseball gear for the soldiers—whenever they had time off from the brutal trench warfare.

Secretary of War Newton D. Baker initially towed the hard line that baseball was unessential to the war effort and needed to be shut down, but later softened his stance and allowed the 1918 season to finish in September instead of July. (Library of Congress)

The owners addressed some of the criticism with more than just cutbacks. They offered that the game’s benefaction to the war effort went beyond bucks and bats; as the national pastime, baseball was keeping stateside spirits and patriotism high.

Just a month into the 1918 season, the owners found a critic they couldn’t ignore: Provost Marshall General Enoch Crowder, the director of the military draft. He decreed that by July 1, all draft-eligible men employed in “non-essential” occupations must apply for work directly related to the war—or gamble being called into military service.

Despite pleas for leniency from baseball’s owners, Secretary of War Newton D. Baker agreed with Crowder: Life as a ballplayer was non-essential. Enlist to help stateside, or risk going to the front lines of Europe.

Baseball was given a reprieve of sorts; the “work or fight” deadline was delayed two months to September 1. And even then, the owners had to furiously lobby for a deadline extension for World Series participants. The government reluctantly gave it to them.

So while the season would be shortened by another two weeks, it wouldn’t be killed in midstride. But with the vast number of players—an average of 15 per team—drafted or enlisted before the deadline, teams scrambled to replace veteran players with others of lesser quality and experience.

Who left and who remained shaped up the balance of power in both pennant races.

The reigning National League champion New York Giants began the season practically intact, and it showed in the standings—leapfrogging out to an 18-1 start to hold first place into June. Then the draft breezed through; the Giants’ pitching roster was decimated. Established starters Jeff Tesreau, Rube Benton and off-season acquisition Jesse Barnes were off to war by the time the Giants dropped well back into second place.

That left the top spot to be claimed by the Chicago Cubs, who were rendered relatively untouched by the war. Absent from pennant races over the previous five years, the Cubs cleverly prepared for a potential deprivation of talent in 1918 by stocking up on pitching. Even after the biggest of these additions—Pete Alexander, winner of 94 games over the previous three years at Philadelphia—got quickly scooped up by the army in May, the Cubs had enough skilled pitching left to overwhelm the more depleted NL competition.

Three starters in particular ignited the Cubs—and more importantly, stuck around through Labor Day. Left-handers Hippo Vaughn (1.74) and Lefty Tyler (2.00) furnished the NL’s two best earned run averages. Vaughn also led the league with 22 wins, while Tyler, another off-season addition (from the Boston Braves), chipped in with 19 victories. Claude Hendrix added 20 while losing only seven.

Chicago’s pitching helped make up for its median output from a virtual no-name offense; the only historical name of note that stuck out was first baseman Fred Merkle, though for more dubious reasons. While Merkle’s bonehead stigma remains storied, he could also brag of having the winning knack wherever he went; he was about to play in his fifth World Series in eight years.

BTW: Merkle was also a member of NL pennant winners New York (1911-13) and Brooklyn (1916).

The Babe’s Infant Decade

It took a player with the nickname “Home Run” (Frank Baker) to keep Babe Ruth—who came to bat only 1,110 times, roughly the equivalent of two full seasons—from leading the AL in homers during the 1910s. In terms of home run frequency, however, no one came close to matching Ruth, the Boston ace pitcher quickly transforming himself into the game’s greatest power hitter. (Photo: Library of Congress)

Across town at Comiskey Park, the fall of the Chicago White Sox was just as startling as the rise of the Cubs.

At full strength, most agreed the White Sox remained the best in the American League. But now handicapped like everyone else, the Sox lost most of their star players—while those left behind suffered from off-year performances. Joe Jackson, Eddie Collins, Lefty Williams, Red Faber and Happy Felsch were all eventually scooped away by the military. Eddie Cicotte never heard from the draft board and missed the presence of those who did; after winning 28 the year before, he managed only 12 victories against an AL-high 19 losses. The White Sox crashed to sixth place, 10 games under the .500 mark.

Another strong AL contender, the Boston Red Sox, initially looked too depleted to be a serious threat as well. Player-manager Jack Barry was gone before season’s start, as was left fielder Duffy Lewis—perhaps Boston’s best everyday hitter since the controversial departure of Tris Speaker two years earlier.

Former International League president Ed Barrow replaced Barry as manager and looked around for someone to fill Lewis’ shoes in the outfield. Right fielder Harry Hooper suggested to Barrow that he deal forth an ace from the mound: Babe Ruth.

The 23-year-old southpaw had flowered into one of the AL’s best pitchers of recent years, and moreover showed tantalizing promise at the plate. Ruth not only hit as well as the everyday players, but showed unlimited power; in his first three full years at Boston, Ruth averaged a home run every 39 at-bats—while it took 457 for his teammates to eke one out.

Hesitant at first, Barrow slowly began to play Ruth routinely in the outfield, crossing his fingers that Ruth would deliver while the rest of his young, talented staff wouldn’t get swept into the service.

Barrow’s hopes paid off on both accounts, and the Red Sox survived a close pennant race with Cleveland to join the Cubs in the World Series. Ruth became the only Red Sox player to bat .300; his 11 round-trippers earned him his first of many, many home run titles; and his slugging percentage, at .555, easily outdistanced all other major leaguers. On the mound, Carl Mays (21-13), Sad Sam Jones (16-5) and Bullet Joe Bush (15-15) did stick around to give the Sox superior pitching. Ruth even managed to leave the outfield and take the mound 20 times in 1918—winning 13, losing seven, and producing a strong 2.21 ERA.

BTW: Ruth had two other home runs reduced to triples because they were each hit in extra innings with a man on first base—and since the rules of the time decreed that only the winning run could be acknowledged, Ruth could only be given three bases.

Although the career of Ruth, the pitcher, was rapidly drawing to a close—bowing to Ruth, the Sultan of Swat—the World Series would provide him a last great hurrah on the mound.

Ruth started Game One and silenced the Cubs with a six-hit, 1-0 shutout, setting the tone for a very low-scoring Series. After the teams split the next two games, Ruth came back to the mound for Game Four and continued his scoreless mastery, finally succumbing to a two-run rally by the Cubs in the eighth inning. It ended a streak in which Ruth had shut down opponents in World Series play for 29.2 straight innings; in spite of all of the staggering feats of sluggery that lay ahead for Ruth, he would always consider this milestone to be the proudest of his career.

BTW: Whitey Ford would surpass Ruth’s consecutive scoreless inning mark in 1961—the same year Roger Maris eclipsed his season home run record.

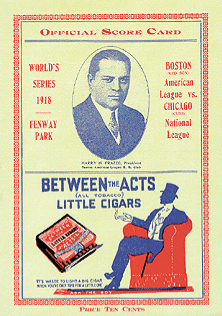

The scorecard for the 1918 World Series won by the Red Sox prominently features Boston owner Harry Frazee—whose actions over the next five years would lay the foundation for the team’s inability to win another Fall Classic until 2004.

The National Commission, the governing body of organized baseball, had earlier authored a new rule in which second, third and fourth place teams would share in the World Series earnings, siphoning away money once awarded solely to those playing in the Series. It would have helped had the owners told the players; they didn’t. Once Red Sox and Cub players found out, they were so outraged that they refused to take the field for Game Five.

AL president Ban Johnson, in a less-than-sober state, entered the clubhouses and lowered his booming voice upon the players to put their trivial differences in perspective; why cause a stir over a few hundred bucks when Americans were dying in Europe? The players, without entirely endorsing Johnson’s state of being, nevertheless got his point and carried on with Game Five an hour later than scheduled.

BTW: The payout to players in the 1918 World Series would be the lowest ever: $1,102 for the Red Sox, $671 for the Cubs.

The Red Sox would eventually win the Series in six games—their fourth championship in seven years.

And their last for nearly a century.

A stark, melancholy contrast was indeed drawn between players striking for more World Series shares and those fighting the Great War. While many players performing stateside duties were accused of receiving preferential treatment, others in Europe clearly were not. Pete Alexander—the game’s best pitcher of the day—served the front lines of France and suffered from shellshock, loss of hearing, and developed symptoms of epilepsy that later would drive him toward alcohol abuse. Ty Cobb and Christy Mathewson were part of a gas defense drill gone horribly wrong; Cobb escaped unharmed, but Mathewson inhaled a fair amount of poison gas. He gradually deteriorated and died of tuberculosis seven years later at the age of 45.

After winning 94 games over his previous three years, Pete Alexander was sent to the front lines of the Great War and returned mentally scarred, developing numerous symptoms as a result of shellshock.

Rumor abounded that if war continued into 1919, the majors would cease operations completely. It became a moot point when Germany formally surrendered on November 11, 1918, ending the Great War—a.k.a., World War I.

Major league owners had already done what they could to recoup their losses from the war-shortened campaign of 1918. When the season ended on September 1, they released all players as free agents—and then with a wink and a nod to one another, signed them back to the same teams for the 1919 season, in effect saving $200,000 in player salaries they otherwise would have had to pay. When the ballplayers returned to life as normal, they fumed over the lost wages. A few sued and got their money, but most were afraid to do so, fearing they’d be blacklisted. Two-time NL batting champion Jake Daubert was the most publicized of those who sued; he got his “back pay” in an out-of-court settlement, but was promptly traded from Brooklyn to Cincinnati.

The seeds of discontent had been sown among ballplayers everywhere.

It would come back to haunt the owners in blindsiding fashion.

Forward to 1919: Say it Ain’t So Eight members of the Chicago White Sox plot the unthinkable and throw the World Series against Cincinnati.

Forward to 1919: Say it Ain’t So Eight members of the Chicago White Sox plot the unthinkable and throw the World Series against Cincinnati.

Back to 1917: Clean Sox The Chicago White Sox—the team that would throw the 1919 World Series—plays it strong and honest against the New York Giants.

Back to 1917: Clean Sox The Chicago White Sox—the team that would throw the 1919 World Series—plays it strong and honest against the New York Giants.

1918 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1918 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1918 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1918 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1910s: The Feds, the Fight and the Fix The majors suffer growing pains as they deal with a fledgling third league, increased scandal and gambling problems, and a brief interruption from the Great War.

The 1910s: The Feds, the Fight and the Fix The majors suffer growing pains as they deal with a fledgling third league, increased scandal and gambling problems, and a brief interruption from the Great War.