THE YEARLY READER

1969: The Amazin’ Mets

The laughingstocks of baseball for much of the 1960s, the New York Mets perform a rapid and dramatic turnaround, capturing the hearts of fans everywhere with an eye-popping World Series performance against the Baltimore Orioles.

Fifty-thousand Shea Stadium fans, who had loyally suffered with the New York Mets since their 1962 inception, go wild seconds after their team puts the finishing touches on a blindsiding world title over the powerful Baltimore Orioles. (Associated Press)

In the early 1960s, President John F. Kennedy pledged to put a man on the moon by the end of the decade. A lot of people thought he was overreaching.

Had the President instead said that the hopeless, lovably pathetic New York Mets would win the World Series by decade’s end, they would have thought he was crazy.

Yet, amazingly, both missions would be accomplished by 1969.

For much of the 1960s, the Mets had cemented themselves as the laughingstocks of baseball. Starting with their famously awful debut in 1962 in which they suffered a modern-record 120 losses, the Mets lost an average of 108 games through their first six years—much of it led by manager Casey Stengel, the aging clown prince watching his 24 stooges perform pratfalls on the playing field. The fans—and even the players, it sometimes seemed—reveled in the losing image. If the Mets had a mission statement, it might have read: “To seek new ways of losing so as to entertain our newfound faithful.”

While NASA was on track to meet its deadline, the Mets were still trying to figure out how to design a proverbial launching pad. Forget 1969, New Yorkers quipped; it seemed a safer bet that the Mets wouldn’t win anything until 2001.

All bad things must come to an end, and the Mets certainly began to sense by 1967 that the novelty of comic defeat was beginning to wear thin on the Shea Stadium fan base, itself beginning to thin out in numbers. The idea of winning became a higher priority.

Fortunately by this time, the Mets had been graced with a new wave of young talent insistent on shedding the team’s losing image. At the core of this group were three highly-touted pitchers: Tom Seaver, a USC grad scooped up by the Mets after baseball voided an earlier pact he signed with the Atlanta Braves; Jerry Koosman, a southpaw from Minnesota who would form a fine accompaniment with Seaver; and Nolan Ryan, a rural Texas-bred hurler who threw so hard, every time his fastball hit the catcher’s mitt it sounded like a rifle going off.

BTW: Seaver’s deal with Atlanta was nixed because it was ruled he was signed before his college eligibility was up.

To give these players the discipline they needed to succeed at the major league level, the Mets brought in a new manager by trading for him. Gil Hodges, one of the Brooklyn Dodgers’ Boys of Summer, was given to the Mets by the Washington Senators for $100,000 and pitcher Bill Denehy.

BTW: For the Senators’ sake, the $100,000 hopefully went far; Denehy, ultimately a 1-10 lifetime pitcher, did not.

Under Hodges, the Mets would creep to ninth in the 10-team National League race in 1968, though the team’s 73-89 record was easily its best yet. Hodges’ tough-minded but fair treatment of his players earned their respect and set up the likelihood for further progress in 1969.

The pundits nevertheless expected the usual from the Mets in the newly-created six-team NL Eastern Division—with some even predicting the Mets to finish last behind the first-year Montreal Expos. If the Mets were to make a statement to the contrary, it didn’t happen on Opening Day when they lost to said Expos at Shea, 11-10.

The Mets entered June below the .500 mark, but then reeled off 11 straight victories to serve notice. Few paid attention; all eyes instead were on the front-running Chicago Cubs, who under Leo Durocher were off to a flying start with eventual 20-game winners Ferguson Jenkins and Bill Hands, and star sluggers Billy Williams, Ron Santo and 38-year-old shortstop Ernie Banks—who at long last had promising visions of his first trip to the postseason.

The Mets and Cubs engaged in a series of heated contests through the summer—with the Mets usually coming out on top—but it did New York little good in its goal of chasing down the Cubs. By mid-August, Chicago maintained a commanding 9.5-game lead on the Mets, and the September sage factor purely favored the Cubs, an established team with proven stars compared to the Mets’ talented yet relatively green young guns. And besides: These were the New York Mets, who never knew from anything but last place, right?

Like a blindsiding nighttime tornado, the Mets swept through the rest of the regular season schedule and spun the Cubs around upon their rear ends. New York won 38 of its final 49 games—including two more crucial victories over the Cubs in early September—to help spark a ten-game win streak and surpass Chicago in the standings.

Suddenly the Mets, who for so long seemed to have losing in their lifeblood, couldn’t lose if they tried. They won both ends of a doubleheader over the Pittsburgh Pirates on September 12 when their two starting pitchers—Koosman and Don Cardwell—knocked in the only runs in a pair of 1-0 victories. Three days later, St. Louis pitcher Steve Carlton set an all-time major league record against the Mets with 19 strikeouts—and the Mets still beat him, 4-3. New York clinched the NL East at its final home game before a week-long, season-ending road trip; Shea Stadium groundskeepers would need that week to repair the turf, ripped apart by 50,000 rabid fans celebrating the unbelievable.

BTW: Having drawn well when they stank, the Mets were sure to pack the house with their newfound winning. They did, attracting over 2.1 million fans.

Offensively, the Mets’ astounding 100-62 finish was accomplished with mirrors behind Gil Hodges’ heavily platooned lineup. Eleven different players appeared in 100 or more games, but only two—outfielders Tommie Agee (a club-high 26 home runs and 76 RBIs) and Cleon Jones (third in the NL with a .340 average)—played in over 125.

Pitching was the undeniable strength of the 1969 Mets. Tom Seaver, appropriately earning his nickname “Terrific Tom,” won his last 10 decisions to finish at 25-7 with a 2.21 earned run average. Koosman won his last five to end the year at 17-9 and a 2.28 ERA. A sharp bullpen was anchored by Tug McGraw and Ron Taylor. Nolan Ryan, limited by groin problems, won six of nine decisions and struck out 92 batters in 89 innings.

As tough an opponent as the Mets became, the Cubs’ biggest foe toward the end may have been Leo Durocher. The firebrand Chicago manager kept using his best players day in and day out, and the resulting fatigue was reflected in a 16-25 record down the stretch. In terms of leadership, Durocher didn’t exactly lead by example when, citing an “illness” in late July, he gave himself a few days off for some presumed bedrest—only to be discovered playing hooky with his son at a summer camp in Wisconsin.

Greatness Without Glory

The 1969 season would be the closest Ernie Banks would ever get to the playoffs. The outstanding Cub shortstop is near the top of a list of Hall of Famers who played at least 15 years and never made it to a postseason nor played for a first-place team after 1900.

The Mets entered the first-ever National League Championship Series (NLCS) against the Western Division champion Atlanta Braves, knowing they had won seven more games overall and 8 of 12 in head-to-head play over the Braves during the regular season. Yet the relatively inexperienced Mets still were considered underdogs to a team brimming with World Series history of seasons past in Hank Aaron (who at age 35 hit .300 with 44 homers) and Orlando Cepeda. It also figured in many people’s minds that the Braves were peaking, having taken 17 of their last 21 games to win a tightly-contested NL West race over San Francisco and Cincinnati.

BTW: Located 200 miles from the Atlantic, Atlanta’s placement into the NL West was not a case of baseball flunking a geography test, but of keeping more westbound cities Chicago and St. Louis in the NL East to preserve long-time rivalries.

In an ironic role reversal for the Mets, strong hitting would bail out weak pitching in the NLCS, as New York hit .327 with six home runs in a three-game sweep of the Braves—earning more converts nationwide in the process.

The Mets’ stunning turnabout could not be matched within the American League, though what the Baltimore Orioles accomplished in dominating the AL competition was no less impressive.

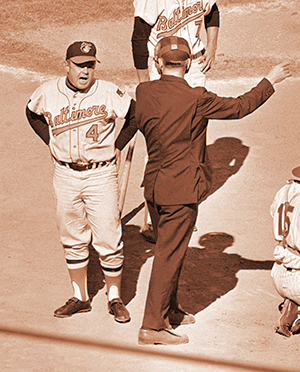

Sliding about for a few years after their 1966 World Series triumph, the Orioles regained new steam at the helm under manager Earl Weaver. Ever since John McGraw left the game, umpires thought they had it easy—until Weaver came along. Weaver was very much made from the McGraw mold: Short, punchy, temperamental, and a winner. Yet Weaver was strategically miles apart from McGraw, favoring the three-run homer while eschewing modern-day essentials left over from the deadball era such as the bunt and hit-and-run.

In what would become a familiar sight for Baltimore fans, second-year manager Earl Weaver gets tossed in Game Four of the World Series. The pugnacious yet successful Oriole skipper would be ejected six times overall in 1969. (Associated Press)

With Weaver in command, the Orioles became a colossus. They won 109 games for him in his first full season, practically lapping the defending champion Detroit Tigers by 19 games in the AL East. First baseman Boog Powell, statistically asleep the previous two years, reawakened with a team-high 37 home runs and 121 RBIs. Frank Robinson was right behind him with 32 homers and 100 RBIs; both batters hit over .300. On the mound, the strong Orioles rotation was led by Dave McNally (20-7, 3.21 ERA), who jumped out to an AL record-tying 15-0 start; Jim Palmer (16-4, 2.34 ERA), who won 11 in a row at one point following a year-plus’ worth of shelf life due to back problems; and Mike Cuellar (23-11, 2.38 ERA), who showed signs of brilliance in Houston and was nothing but after being traded to Baltimore for 1969.

The Orioles would have little problem with the AL West-winning Minnesota Twins in the first ALCS, surviving extra innings to win the first two games before breezing, 11-2, to complete the three-game sweep.

BTW: Winners of 97 games, the Twins were the first of many teams to thrive and then “deal with” pugnacious manager Billy Martin, whose run-ins with team players and management got him fired after just one season.

That the New York Mets again rated as underdogs to the Orioles in the World Series was no sign of disrespect; Baltimore clearly looked superior in almost every facet of its game. And when Don Buford blasted Tom Seaver’s second pitch of Game One over the fence—setting the pace for a 4-1 Orioles victory—the Mets finally appeared to meet their match, and then some.

But a funny thing happened on the way to the victory podium for the Orioles.

Starting in Game Two, the Orioles were thoroughly shut down—if not first by the sterling New York pitching, then by the gloves of the Mets’ seemingly omnipresent defense. It was a dual-layered assault that would completely dumbfound the Baltimore juggernaut—not to mention a stunned nationwide audience that was tuned in and looking on.

Jerry Koosman retired the first 18 Orioles he faced on his way to a 2-1 Game Two win. In Game Three, pitchers Gary Gentry, Nolan Ryan and outfielder Tommie Agee—who robbed the Orioles of at least five runs with two tremendous running catches—helped to shut down the Orioles on four hits, 5-0. Seaver went the distance in a tense, 10-inning 2-1 win in Game Four, the unofficial save of which went to another Mets outfielder, Ron Swoboda—whose sprinting, fully-extended diving catch kept the potential winning Baltimore run from scoring in the ninth, preserving the game for extra innings and keeping the Mets alive. Some say that Swoboda’s may be the greatest ever in World Series play—Willie Mays’ famous 1954 over-the-shoulder grab included.

BTW: Ryan’s Game Three relief role would be the only World Series appearance of his 27-year career.

Game Five would provide the Orioles more frustration, added with a dose of poor luck. With Baltimore taking a 3-0 lead into the sixth, Frank Robinson appeared to be hit by a Koosman pitch—only to have it ruled a foul off the bat by home plate umpire Lou DiMuro; Robinson finished the at-bat by striking out. In the Mets’ half of the sixth, Cleon Jones also appeared to be hit, on the foot—but DiMuro again ruled otherwise. In a move that recalled Milwaukee’s Nippy Jones in the 1957 Series, the Mets showed DiMuro the ball—which had shoe polish stroked upon it. DiMuro changed his mind, gave Jones the base—and Donn Clendenon promptly smacked a two-run homer, igniting the Mets as they later scored one in the seventh to tie, then two in the eighth to take the lead going into the ninth. All through the rally, Koosman kept the Orioles in check and secured the miracle at Shea.

BTW: Koosman later claimed the ball rolled into the dugout without shoe polish; Gil Hodges told him to wipe it off his foot and put it back out, which he did.

As delirious Mets fans—most of them too young to remember the dominant days of the Brooklyn Dodgers and New York Giants—bore down once more on the Shea Stadium grass for souvenirs, New York City readied the streets for its second ticker-tape parade in two months.

The first was for the Apollo 11 astronauts.

The second would be for the Amazin’ 1969 Mets, the world champions of baseball.

Forward to 1970: One for the Brooks The incomparable Brooks Robinson cleans up at third base on the world’s biggest baseball stage for the Baltimore Orioles.

Forward to 1970: One for the Brooks The incomparable Brooks Robinson cleans up at third base on the world’s biggest baseball stage for the Baltimore Orioles.

Back to 1968: Year of the Pitcher Batting averages plummet as major league pitchers dominate the game of baseball as never before.

Back to 1968: Year of the Pitcher Batting averages plummet as major league pitchers dominate the game of baseball as never before.

1969 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1969 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1969 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1969 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1960s: Welcome to My Strike Zone In a decade where baseball as a tradition is turning stale with America’s emerging counter-culturism, major league owners see its biggest problem to be, of all things, an overabundance of offense in the game. The result? An increased strike zone, further contributing to a downward spiral in attendance, but greatly aiding an already talented batch of pitchers.

The 1960s: Welcome to My Strike Zone In a decade where baseball as a tradition is turning stale with America’s emerging counter-culturism, major league owners see its biggest problem to be, of all things, an overabundance of offense in the game. The result? An increased strike zone, further contributing to a downward spiral in attendance, but greatly aiding an already talented batch of pitchers.

Two-time batting champion Tommy Davis looks back at a well-traveled career that included high times with the Dodgers of the early 1960s—and interesting times with Jim Bouton and the 1969 Seattle Pilots.

Two-time batting champion Tommy Davis looks back at a well-traveled career that included high times with the Dodgers of the early 1960s—and interesting times with Jim Bouton and the 1969 Seattle Pilots.