THE YEARLY READER

1970: One For the Brooks

In a preview of the decade to come, the Cincinnati Reds and Baltimore Orioles dominate and square off in the World Series—highlighted by Orioles third baseman Brooks Robinson’s defensive heroics.

Nothing—absolutely nothing—was going to get past Brooks Robinson during the 1970 World Series. The third baseman’s numerous gems, coupled with his potent hitting, propelled the Orioles to a world title over Cincinnati. (Associated Press)

Brooks Robinson took the first ground ball hit to him in the 1970 World Series and threw it over the head of first baseman Boog Powell.

Oh boy, thought Robinson, this is not the way to get another Series started.

The early gaffe would be the one and only blemish for Robinson, not so arguably the best defensive third baseman in history. Exhibiting a flawless and spectacular blend of fielding seldom seen before or since, Robinson lifted his Baltimore Orioles to a commanding Fall Classic triumph over the Cincinnati Reds, erasing bad memories of a Series gone haywire the year before against the Amazin’ Mets.

A gentleman of a ballplayer, Robinson was immensely popular with Baltimore fans who pinned the title “Mr. Oriole” upon him. The reasoning went beyond adoration. A native of Little Rock, Arkansas, Robinson began his big league career with the Orioles at the tender age of 18, a year after the team arrived in Baltimore from St. Louis; he’d been there ever since. It took awhile for his hitting game to take hold, but he became a prominent enough batter to receive one AL Most Valuable Player award in 1964 through a spike in his offensive numbers—setting personal bests with a .317 batting average, 28 home runs and 117 runs batted in. But he still often wasn’t clumped with the grand hitters of the day, people like Mays, Aaron, Mantle and Clemente. His nationwide identity crisis deepened in 1966 when the Orioles won the World Series primarily behind another guy named Robinson—Frank, the superstar slugger.

But Brooks Robinson’s role with the Orioles wasn’t popularized for getting hits at the plate, but for taking them away in the field.

Robinson was the best defensive third baseman ever to play the game of baseball. He worked tirelessly in his early years to fine tune his glovework, and it all began to pay off in 1960 with the first of 16 straight Gold Gloves, the first of 15 straight All-Star Game appearances, and the first of nine years during the 1960s leading AL third basemen in fielding percentage. The uncanny magnetism to scoop anything hit near and not so near Robinson made him clearly without peer.

Cooling Off the Hot Corner

Ever since he led American league third basemen in fielding percentage for the first time in 1960, Brooks Robinson undoubtedly played to a consistently higher level through 1970. Here’s how he compared to his peers during this time.

The Orioles, intent on overcoming their downfall in the 1969 World Series against the Mets, bullied through the AL competition as if in a foul and vengeful mood. Behind manager Earl Weaver, the Orioles once again exhibited little or no weaknesses and ran away with the AL East title on a dominant 108-54 record. Their highly balanced offense was led by Boog Powell, another popular Oriole who captured the AL MVP with a .297 batting average, 35 home runs and 114 RBIs. Baltimore’s 3.15 earned run average was the AL’s best, and they fielded three of the league’s seven 20-game winners—including Mike Cuellar and Dave McNally, who co-led the AL with 24 each. Defensively, the Orioles proved that great fielding didn’t begin and end with Robinson, as Gold Gloves were also handed out to center fielder Paul Blair and second baseman Davey Johnson.

BTW: Underscoring the Orioles’ knack to reach base, Powell walked 104 times to finish third in AL on-base percentage at .417.

The Minnesota Twins, now piloted by Bill Rigney after the tumultuous ousting of Billy Martin, didn’t lose a step by winning their second straight AL West title. But by not adding a step, they were doomed to failure once more against the mighty Orioles in the ALCS.

Much like the year before, the Twins were knocked out by Baltimore in three straight. But at least in 1969 they gave the Orioles a fight; this time, there was little punch in a team blown out in all three losses by a combined score of 27-10.

Victims of a big upset in the 1969 World Series, the Orioles were determined not to be underwhelmed by their 1970 Series opponent: The Cincinnati Reds. But given the emerging powerhouse rising out of sparkling new Riverfront Stadium, the Reds were hardly one to get non-pulsed about.

The Reds were the youngest team in the majors, with all of their everyday players, starting pitchers and top relievers all under the age of 30. Their rookie manager was also the youngest, though at the age of 36, George “Sparky” Anderson looked older than half of the game’s other managers with his fast-graying hair and gravelly voice. Anderson’s confident and feisty leadership—which led to his nickname years before as a minor league player—was key to providing his players with a newfound sense of tenacity.

Anderson was not above selling his inner thoughts to the press. It was one thing for Anderson to predict at spring training that the Reds would win the National League West, a bold promise given the tough and experienced competition expected from divisional rivals Atlanta, Los Angeles and San Francisco. But Anderson went further; he said the Reds would win it by 10 games.

Sparky would collect.

The Reds stormed out of the gate and never let up, losing hold of first place only for a single day in the season’s first week. They had fulfilled Anderson’s promise even before the season was halfway over, achieving a 10-game lead that would never regress. When the schedule ran itself out, the Reds had won a franchise-record 102 games, finishing 14.5 over the second-place Dodgers.

BTW: The Reds’ best record, by percentage, remained at 96-44 from 1919.

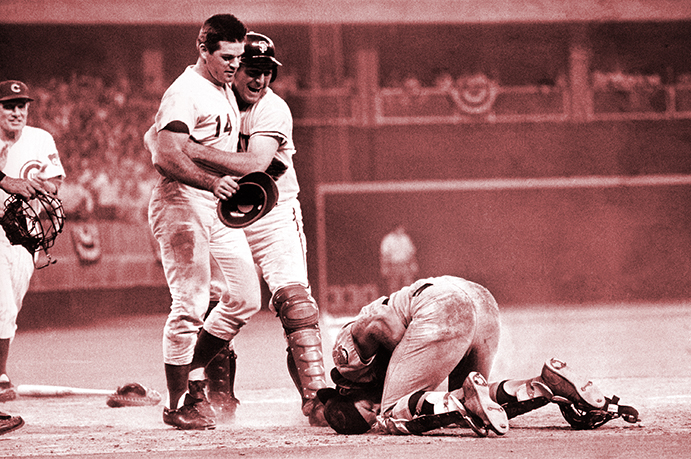

Pete Rose shows a national audience that he’ll give his all even in an ‘exhibition’ such as the All-Star Game, bowling over Cleveland catcher Ray Fosse to score the winning run for the National League. Rose was slightly hurt but was fine within days; the career of Fosse, who suffered a separated shoulder, never recovered. (Associated Press)

As it would throughout the 1970s, the Reds were powered mostly by a prodigious offense. Catcher Johnny Bench, who ignited a trend behind the plate by catching one-handed, devastated opposing pitching when he came to bat—leading the majors with 45 home runs and 148 RBIs in only his third full season at age 22. Cuban native Tony Perez might have grabbed the NL MVP had it not been for Bench, the third baseman hitting .317 with 40 homers and 129 RBIs. Lee May added 34 homers and 94 RBIs at first base. Cincy’s three starting outfielders—Pete Rose, Bobby Tolan and Bernie Carbo—each hit above .310; Tolan led the majors with 57 stolen bases.

BTW: Perez finished third in the MVP voting, behind Bench and Billy Williams.

Though statistically in the shadows, the 29-year-old, switch-hitting Rose was clearly the inspirational leader for the Reds—if not the City of Cincinnati, where he was born and raised.

Most baseball nicknames are derived from inside jokes, but it didn’t take an insider to figure out why Rose was called Charlie Hustle. Not blessed with great speed—Rose rarely stole more than 10 bases a year—he made up by using every ounce of grit and determination to get two, maybe three, bases on a play when most anyone else would have settled for one. On the crack of a bat, Rose knew how far he intended to go on the basepaths, and he generally succeeded.

BTW: “Charlie Hustle” was pinned on a young Rose by Yankees pitching great Whitey Ford after watching him sprint to first on a walk.

The Charlie Hustle image grabbed the national spotlight when, before his hometown fans at Riverfront Stadium, Rose bowled over catcher Ray Fosse at the All-Star Game—winning the game for the NL and ruining Fosse’s career, the Cleveland catcher never fully recovering from a shoulder separation. It showed the world—and certainly his opponents, who probably already knew—that Rose would give a million per cent whether he was playing an intrasquad tune-up or the seventh game of the World Series.

The switch from rustic Crosley Field to modern Riverfront Stadium was timely for the Reds, who won with equal vigor at both parks. The team’s dominant and lively play combined with the new stadium’s presence resulted in a team-record 1.8 million fans.

BTW: The Reds had drawn a million fans only four times at Crosley, with 1.1 million the previous high-water mark in 1956.

The Rise and Fall of Fake Grass

Before 1970, only the Houston Astrodome and the infield at Chicago’s Comiskey Park were outfitted with artificial turf. But in 1970, the synthetic material players and purists loved to hate was rolled out in St. Louis and at new ballparks in Pittsburgh and Cincinnati—and by the mid-1970s, over a third of all major league venues would follow suit before retracting. By 2010, only domed facilities in Toronto and Tampa Bay continued to perform on the fake sod.

For the NLCS, the Reds would square off against the Pittsburgh Pirates, brought back to the postseason for the first time since 1960 thanks to the return of manager Danny Murtaugh, marking his second comeback as Pirates leader. Like the Reds, Pittsburgh had strong hitting, no-name pitching and a new multi-purpose, artificially turfed stadium whose looks and name (Three Rivers Stadium) confused many with Riverfront Stadium. But there was no confusing the Reds’ towering level of superiority compared to the Pirates.

While few were surprised that Pittsburgh would go three-and-out against Cincinnati in the NLCS, what was surprising was that the Reds’ unknown soldiers—their pitchers—would be the stars. The Cincinnati staff allowed three Pittsburgh runs through the entire series, pretty much bailing out a Reds offense that played below its game with only three runs in each of its victories.

Amazingly, the Reds’ rotation had risen to the occasion in the NLCS as a wounded bunch, with three of its five starters—including left-handed 20-game winner Jim Merritt—either on the shelf or threatening to land there. That, Sparky Anderson knew. What his Reds were unprepared for as they entered the World Series was how unworldly the opposing third baseman was going to be in stopping them cold.

BTW: The 26-year old Merritt developed a sore arm that sent his career into a tailspin, winning only seven more games after 1970.

Brooks Robinson surveyed the artificial turf at Cincinnati before Game One and, although not wild about playing on a surface akin to a parking lot, admitted that its predictable infield bounces would make him feel defensively “invincible” at third base. Proof of that came in the Reds’ sixth, when Lee May led off with a smash down the third base line—which Robinson snared at with a brilliant, diving backhanded stab. Having deprived the Reds of the go-ahead run in a 3-3 game, Robinson provided it himself an inning later with a solo home run that proved to be the winning score.

Robinson’s astounding defense continued throughout the Series at a level that he later would say was the most consistently brilliant of his career, leaving fans open-mouthed and Cincinnati players shaking their heads in utter frustration. In Game Three, “Hoover”—as the Reds had begun to nickname him—made for an especially sparkling exhibition at the hot corner by sending Reds hitters back to their dugout with one great play after another.

As if his defense wasn’t enough, Robinson was equally rough on Cincinnati pitching at the plate. He knocked in the tying run and scored the winner in a 6-5 Game Two comeback, erasing an early 4-0 Reds lead; in Game Three, he belted a two-run double in the first inning to set the Orioles on their way to a 9-3 rout; and in Game Four, he went 4-for-4 with his second Series home run, although it wasn’t enough as the Reds avoided the sweep with an eighth-inning rally to win, 6-5.

Fittingly, Robinson fielded and threw the final out in Game Five to extinguish what little suspense was left to an easy Series triumph; there was no suspense in the Series MVP voting, given to Robinson for stellar defense and a 9-for-21 (.429) performance at the plate.

BTW: His ALCS numbers included, Robinson batted .485 with two home runs and six RBIs for the 1970 postseason.

The Orioles had triumphed, the rotten misfortune of 1969 was turned around, and the man behind it all, the one formerly standing in the shadows alongside the national spotlight, finally basked in its powerful glow.

Forward to 1971: Dynasty on the Rise After years of constant losing, the colorful Charles Finley finally has a winner with the A’s in Oakland.

Forward to 1971: Dynasty on the Rise After years of constant losing, the colorful Charles Finley finally has a winner with the A’s in Oakland.

Back to 1969: The Amazin’ Mets The New York Mets, perennial laughingstocks of the 1960s, perform a stunning about-face to end the decade.

Back to 1969: The Amazin’ Mets The New York Mets, perennial laughingstocks of the 1960s, perform a stunning about-face to end the decade.

1970 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1970 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1970 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1970 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1970s: Power to the Player Curt Flood’s sacrificial stand to win free agency opens the door for the biggest challenge yet to the reserve clause, which is eventually shattered—but not without fans suffering from numerous player strikes and holdouts.

The 1970s: Power to the Player Curt Flood’s sacrificial stand to win free agency opens the door for the biggest challenge yet to the reserve clause, which is eventually shattered—but not without fans suffering from numerous player strikes and holdouts.

Arguably the greatest defensive third baseman in history recalls his most memorable moments and fun times with the Orioles.

Arguably the greatest defensive third baseman in history recalls his most memorable moments and fun times with the Orioles. Billy Grabarkewitz recalls the struggle of reaching the big leagues, his impressive debut with the Dodgers—and why he couldn’t maintain it.

Billy Grabarkewitz recalls the struggle of reaching the big leagues, his impressive debut with the Dodgers—and why he couldn’t maintain it.