THE YEARLY READER

The 1970s: Power to the Player

The 1970s began with the highest-paid major leaguer earning around $150,000. Ten years later, it was the average salary of the common player.

Baseball’s 400% hyperinflation of wages during the 1970s had nothing to do with Watergate, OPEC or the coming Ice Age. It had everything to do with the ballplayer, under the guidance of loyal union leader Marvin Miller, having first the urge, and then the legal strength, to assert himself against financially scrupulous owners, who had stood content behind the adamantine reserve clause—until the players, backed by the courts, tore it to shreds in 1975. The rules of the game changed; overnight, baseball’s lords went from slave masters to hustlers, forced to pitch and seduce free agents who finally had the advantage of choice. Fearing that they’d fall behind if they didn’t spend on free agents, the owners started spending on free agents. And to the players came the long-overdue spoils.

The advent of free agency destroyed one dynasty when mercurial Oakland A’s owner Charles Finley refused to bid on anyone, and helped create another when George Steinbrenner rebuilt the New York Yankees as the best team money could buy.

Baseball’s other powerhouse of the 1970s managed to stay largely resilient from the perils of free agency. The Cincinnati Reds were consistent winners from start to finish, averaging 95 victories a year while securing six divisional titles, four National League pennants and back-to-back World Series championships in 1975-76. The Reds’ ultra-potent offense—nicknamed the Big Red Machine—formed a destructive stat pack of major talents: Johnny Bench, Pete Rose, Joe Morgan, Tony Perez and George Foster, among others. Under the lively direction of Sparky Anderson, the Reds commanded respect from opponents who paid a heavy price if they didn’t give it. If the Yankees of the 1950s were compared to U.S. Steel, then the Reds of the 1970s—with their synthetic uniforms, synthetic grass and outfield walls marked in meters as well as feet—could have easily been synonymous with IBM.

Aesthetically, baseball went through some of its most radical changes during the 1970s. The trend of multi-purpose stadiums made artificial turf more of a necessity than a novelty; by decade’s end, nearly half of the teams were playing on it. Hundred-foot hops, infield seam hits and carpet burns from sliding fielders became the norm for players who rather would have done without the fake grass.

Then there were the uniforms. After generations of home teams wearing whites and visitors donning grays, baseball experienced a revolution of color in the 1970s. The Houston Astros took the fashion coup d’état to extremes when, in 1975, they introduced revamped jerseys that included a horizontal rainbow of bright warm colors. Combined with the change to double-knit, buttonless tops, the splashy uniforms of the 1970s had the majors’ newfound millionaires and hundred-thousandaires resembling weekend warriors on a softball field.

Forward to the 1980s: Corporate Makeover Baseball enjoys a healthy boom on several fronts, with increased attendance, corporate sponsorship and memorabilia sales; players also continue to enjoy skyrocketing salaries, but some abuse their newfound riches by delving into illegal drugs.

Forward to the 1980s: Corporate Makeover Baseball enjoys a healthy boom on several fronts, with increased attendance, corporate sponsorship and memorabilia sales; players also continue to enjoy skyrocketing salaries, but some abuse their newfound riches by delving into illegal drugs.

Back to the 1960s: Welcome to My Strike Zone In a decade where baseball as a tradition is turning stale with America’s emerging counter-culturism, major league owners see its biggest problem to be, of all things, an overabundance of offense in the game. The result? An increased strike zone, further contributing to a downward spiral in attendance, but greatly aiding an already talented batch of pitchers.

Back to the 1960s: Welcome to My Strike Zone In a decade where baseball as a tradition is turning stale with America’s emerging counter-culturism, major league owners see its biggest problem to be, of all things, an overabundance of offense in the game. The result? An increased strike zone, further contributing to a downward spiral in attendance, but greatly aiding an already talented batch of pitchers.

The incomparable Brooks Robinson cleans up at third base on the world’s biggest baseball stage for the Baltimore Orioles.

The incomparable Brooks Robinson cleans up at third base on the world’s biggest baseball stage for the Baltimore Orioles. After years of constant losing, the colorful Charles Finley finally has a winner with the A’s in Oakland.

After years of constant losing, the colorful Charles Finley finally has a winner with the A’s in Oakland. Major league ballplayers go on strike for the first time, leaving behind a bitter taste for angry fans.

Major league ballplayers go on strike for the first time, leaving behind a bitter taste for angry fans. Six mediocre teams stumble and bumble with one another in a memorable National League East race.

Six mediocre teams stumble and bumble with one another in a memorable National League East race. Hank Aaron’s long and personally painful ride to home run history comes to a successful conclusion.

Hank Aaron’s long and personally painful ride to home run history comes to a successful conclusion. America’s passion for baseball is re-awakened with, arguably, the greatest World Series ever between Boston and Cincinnati.

America’s passion for baseball is re-awakened with, arguably, the greatest World Series ever between Boston and Cincinnati. Shackled for nearly a century, major leaguers are freed with the death of the reserve clause.

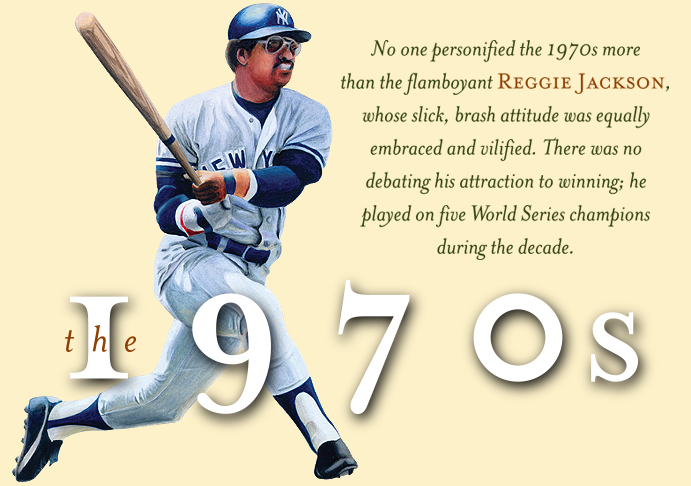

Shackled for nearly a century, major leaguers are freed with the death of the reserve clause. Reggie Jackson caps a stormy first year in New York with a storybook flourish for the Yankees at the World Series.

Reggie Jackson caps a stormy first year in New York with a storybook flourish for the Yankees at the World Series. Bucky Dent’s improbable 163rd-game heroics cap a feverish late-season comeback by the New York Yankees over the Boston Red Sox.

Bucky Dent’s improbable 163rd-game heroics cap a feverish late-season comeback by the New York Yankees over the Boston Red Sox. After years of injury and career decline, Willie Stargell comes alive at 39 to lift the Pittsburgh Pirates.

After years of injury and career decline, Willie Stargell comes alive at 39 to lift the Pittsburgh Pirates.