THE YEARLY READER

1979: One for Pops and His Family

A resurgent, 39-year-old Willie Stargell provides leadership and a little more, stepping it up for the Pittsburgh Pirates and guiding a World Series comeback against the Baltimore Orioles.

Fueled by a career comeback and a sunny disposition that he had never lost, Willie Stargell became a critical guiding force for a young, talented Pittsburgh Pirates team that rallied to a feel-good world championship. (Associated Press)

In the 1971 World Series, the Baltimore Orioles had two chances at home to finish off the Pittsburgh Pirates and stand atop the podium as baseball’s best. They lost both games.

Eight years later, the Orioles got a shot at redemption against the Pirates in the 1979 World Series, this time with three chances—the last two again at home—to win just one.

They lost all three.

In both years, the man who scored the deciding winning tally to cap the Pirates’ comeback was Willie Stargell.

Thirty-nine years young, the burly and effervescent Stargell set the tone for the 1979 Pirates both on the field and in the clubhouse, using father-figure guidance to will his teammates into a unit that was as loose as it was tight-knit, happy to go to the ballpark every day with self-assurance that no one would get in their way to drown out the victory cheer.

Since entering the major league scene at Pittsburgh 17 years earlier, Stargell had emerged as one of baseball’s pre-eminent power sluggers, winning National League home run titles in 1971 (48) and 1973 (44). His titanic blasts are the stuff of legend. Of the 18 home runs hit completely out of Forbes Field over its 61-year history, seven came off the bat of Stargell, who played there only eight years. When the Pirates moved into modern Three Rivers Stadium, distant upper deck seats were painted in different colors to denote where Stargell deposited his tape-measure blasts. And at Dodger Stadium in Los Angeles, Stargell was the only player (until Mike Piazza) to hit it completely out of the ballpark. In fact, he did it twice.

BTW: Stargell led all major leaguers during the 1970s with 295 home runs.

As the 1970s progressed, Stargell digressed. Injuries began to take their toll as Stargell hit middle age, major league-style—the mid 30s—and it appeared he was starting the inevitable downslide toward retirement or the waiver wire. But in 1978, Stargell received a second wind and reclaimed vintage status, especially down the stretch with a .315 batting average, 14 home runs and 51 runs batted in over the last 46 games he appeared. The Pirates responded behind him, revived after a long, weak start to win 37 of their last 49 games—including 24 straight at home—and nearly stole the NL East title from Philadelphia.

Proving that his comeback numbers of 1978 were no fluke, Stargell continued his renaissance into 1979—but he had to pick up a Pirates team that again slumped to begin the season, reached the .500 mark by the end of May, and struggled to stay above it through the All-Star break. Stargell kept team spirits high and created a new type of incentive clause as he began handing out gold “Stargell Stars” to teammates who performed good deeds on the field—a la the tradition of Ohio State football players being rewarded with “buckeye” decals on their helmets.

The Bucs and the Bees

“Stargell Stars” were stitched onto the Pirates’ retro, horizontally-striped box-top caps—part of a colorful, if not outrageous, mix-and-match fashion scheme (below) that Pirates players jokingly compared to bumblebees and taxi cabs. (Image courtesy of Marc Okkonen)

Still, the Pirates’ fourth-place record at the midway point reflected a team in need of help. They would get it from San Francisco, where Bill Madlock was struggling with neither a position (second base) nor batting average (.261) he was used to. Thus the Giants were happy to trade the perennial NL batting champ to Pittsburgh; the Pirates were happy to put him back at third base where he belonged; Phil Garner was happy to move from third base to second, where he belonged; and Madlock was happy to become his old self, hitting .328 with eight homers, 44 RBIs and 21 steals in half-a-season’s work at Pittsburgh.

BTW: Garner replaced an anemic Rennie Stennett (.238, no home runs) at second base.

Madlock’s arrival did the trick for Pirates fortunes on the field. Within a month they had claimed first place, and despite a frenzied September rush by the young, offensively potent Montreal Expos—who briefly retook the Pittsburgh lead away—the Pirates triumphed in the end by 2.5 games for their sixth NL East title of the 1970s.

Stargell’s 32 home runs and 82 RBIs led a dangerous offense that was complemented by leadoff hitter Omar Moreno (.282 average, 77 steals, 110 runs scored) and Dave Parker, a Stargell clone in terms of size, attitude and results (.310, 25 homers, 94 RBIs). Equally dangerous was the Pittsburgh bullpen, which featured a powerful threesome of relievers led by Kent Tekulve, the goose-necked, bespectacled submarine-style thrower who often had the final say against opponents. Along with Enrique Romo and Grant Jackson, the trio combined to toss 345 innings, win 28 games and save another 51, more than not bailing out a veteran starting rotation that was solid yet susceptible to injury.

BTW: Lefty John Candelaria led all Pirates pitchers in wins, with only 14.

Sledge-Jammer

When Pirates players adopted We Are Family as their song for the 1979 season, it gave the song’s disco artists, Sister Sledge, their first and only shot of true national fame. Formed in 1971, Sister Sledge was made up of four sisters—all with the last name Sledge—that would be familiar only within R&B circles before We Are Family.

Along with Stargell’s uplifting leadership, the Pirates were bound together by their self-chosen theme song of the year, Sister Sledge’s disco anthem We Are Family. Hardly a marketing campaign to start, the song took on a life of its own when Pirates management and fans caught on and embraced it as the team slogan.

The Pirates entered the NLCS looking to be the first NL East representative to advance to the World Series since 1973—against a team that thrice throughout the 1970s denied the Pirates from getting there: The Cincinnati Reds.

Without Pete Rose (signed with Philadelphia), manager Sparky Anderson (inexplicably replaced by nomadic retread John McNamara) and with many of the Big Red Machine’s leftover components beginning to rust, the Reds nevertheless overcame—barely—a fast yet punchless Houston Astros team and a sputtering, defending NL champ in Los Angeles, whose pitching went atypically south. Helping to keep the Reds on top was George Foster, who when healthy remained potent as ever with a .302 average, 30 homers and 98 RBIs in 121 games; third baseman Ray Knight—Rose’s replacement—who hit a team-high .318; and Tom Seaver, who in his second full year at Cincinnati led the Reds with a 16-6 mark.

BTW: The Astros were 89-73 despite hitting only 49 home runs—including nine from team leader Jose Cruz.

In the NLCS, the Reds were outshined by a revived Stargell. After slumping through the regular season’s final two months, Stargell reawakened and slammed a three-run, 11th-inning homer in Game One to send Cincinnati to a 5-2 defeat; the Pirates went on to sweep the Reds in three, as Stargell bombed away with two doubles, two home runs and six RBIs. The Reds badly missed the postseason presence of Rose and Anderson—and Joe Morgan, who was there, but went an invisible 0-for-11 at the plate.

Like the Pirates, the Baltimore Orioles would be headed to the World Series for the first time since 1971.

Under the continued pugnacious lead of Earl Weaver, the Orioles had become lost in the American League East spotlight amid the Yankees-Red Sox wars of the late 1970s. But Baltimore exploded back to the top in 1979, its 102 victories all the more impressive considering five of the other six AL East teams posted winning records.

The Orioles’ success came courtesy of Weaver’s two most sacred stratagems: Solid starting pitching and the three-run homer. Joining veteran Jim Palmer as part of a new cast of starters was Dennis Martinez, the Nicaraguan-born workhorse who led the AL in innings (292.1) and complete games (18); and Mike Flanagan, the 27-year-old southpaw who earned the AL Cy Young Award leading the league in more valued categories such as wins (23, against nine losses), shutouts (five) and earned run average (3.08).

BTW: An elbow problem limited the 33-year-old Palmer to a 10-6 record in 22 starts.

At the plate, two switch-hitters keyed the Baltimore attack. First baseman Eddie Murray, 23, continued the remarkable high level of consistency he had displayed from his very first day in the majors two years earlier, rapping out 25 homers, 99 RBIs and a .295 batting average. As heralded as Murray would become, he was partnered with one of the more unheralded sluggers of recent times—right fielder Ken Singleton, whose numbers (.295 average, 35 homers, 111 RBIs) were even more dangerous when throwing in his usual plethora of walks (109).

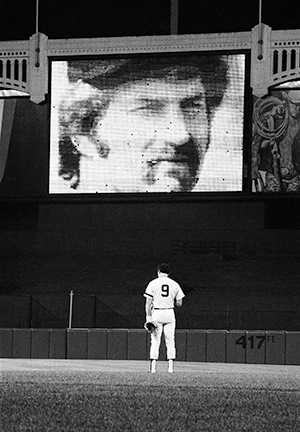

Graig Nettles bows his head in a moment of silence for New York Yankee captain Thurman Munson, who died piloting a plane the day before. The tragedy mentally broadsided the Yankees’ efforts to win their fourth straight AL pennant. (Associated Press)

Hooking up with, and ultimately bowing out to, the Baltimore Orioles in the ALCS would be the California Angels, a franchise lacking any previous postseason experience—though its roster was thick with players who had plenty of it elsewhere.

As one of the more aggressive spenders in the infant years of free agency, Angels owner (and former singing cowboy) Gene Autry built the team out of its recent history of sub-.500 finishes, fireball pitchers and complete lack of offense. His first divisional champion—ending Kansas City’s three-year run atop the AL West—included a lineup with few holes and a wealth of October baseball knowledge: Joe Rudi and Bert Campaneris (Oakland, 1972-74), Rod Carew (Minnesota, 1968-69), Bobby Grich (Baltimore, 1973-74) and Nolan Ryan (New York Mets, 1969).

In terms of performance, the best of the Angels’ veteran lot was another ex-Oriole, Don Baylor—who lived up to his nickname “Groove” by being in one all year, winning the AL MVP with a .296 average, 36 home runs, 22 steals, and AL highs with 120 runs scored and 139 knocked in.

BTW: In his 18 other major league seasons, Baylor never once knocked in over 100 runs.

Having dispensed of the Angels three games to one in the ALCS, the Orioles got off to a flying start at the World Series against the Pirates, similarly taking three of the first four—with the Pirates avoiding the sweep by squeaking out a 3-2, Game Two victory.

Content that history wouldn’t repeat itself from eight years earlier, the Orioles felt good. The Pirates, to their credit, weren’t panicking, as an untroubled Stargell kept the troops off edge with upbeat encouragement. He also needed to pick up manager Chuck Tanner, who learned on the morning of Game Five that his mother had passed away.

BTW: Tanner stayed with the Pirates, as a service for his mother would be held after a scheduled Game Seven.

The Orioles led 1-0 after five innings in Game Five, and were 12 outs away from a Series triumph. They got only nine. The Pirates scored seven times between the sixth and eighth innings and didn’t need to bat in the ninth, winning 7-1 at home. Still, it was advantage, Baltimore—going home to play Game Six and, if necessary, Game Seven.

The Pirates saw to it that Game Seven would become necessary. Starter John Candelaria and closer Kent Tekulve combined to shut down the Orioles 4-0 in Game Six, setting up the winner-take-all. Then, all too appropriately, it was Stargell’s turn: His sixth-inning, two-run homer put the Bucs in front to stay in Game Seven; with a couple late insurance runs that made the final score 4-1, the Pirates iced the three-game comeback to win the Series.

The key to the Pirates’ three-game win streak to end the World Series was the Orioles’ inability to hit. While the Pirates were living up to their vaunted Lumber Company image—hitting .323 overall for the series—the Orioles were the antithetic Slumber Company, scoring just twice over their final three games. Eddie Murray epitomized the Orioles’ untimely sleepwalking at the plate by going hitless in his final 21 Series at-bats.

BTW: Five different Pittsburgh players had at least 10 hits for the Series—and a sixth, Bill Madlock, collected nine.

Stargell’s four hits in Game Seven capped a thunderous postseason in which the Pittsburgh family sire hit .415 (17-for-41) with six doubles, five home runs and 13 RBIs. In the months to follow, Stargell would win enough accolades to fill his own cap with Stargell Stars many times over. He became the only player in major league history to win Most Valuable Player awards for the regular season, league championship series and World Series, while Sports Illustrated bestowed Stargell with its esteemed Sportsman of the Year Award—sharing the honors with the equally affecting Terry Bradshaw, the quarterback whose Three Rivers Stadium co-tenant Steelers were on their way to winning their fourth Super Bowl in six years.

The 1979 World Series would provide the last hurrah for Stargell. Age and injuries would finally and quickly catch up with him, first to part-time status in 1980 and then as bench material in 1981-82.

As popular a retiree as he was an active player, Stargell got his just due in bronze with a sculpture in his honor to help inaugurate Pittsburgh’s PNC Park in April 2001. Stargell would never see his likeness; battling kidney problems, he died a day before the sculpture was unveiled. There is no doubt, however, that Stargell’s upbeat spirit and the uplift he gave the 1979 Pirates remains very much alive within the hearts of Bucs fans everywhere.

Forward to 1980: Finally Philly After nearly a century of trying, the Philadelphia Phillies finally reach the championship podium.

Forward to 1980: Finally Philly After nearly a century of trying, the Philadelphia Phillies finally reach the championship podium.

Back to 1978: The Denting of the Red Sox Bucky Dent’s improbable 163rd-game heroics cap a feverish late-season comeback by the New York Yankees over the Boston Red Sox.

Back to 1978: The Denting of the Red Sox Bucky Dent’s improbable 163rd-game heroics cap a feverish late-season comeback by the New York Yankees over the Boston Red Sox.

1979 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1979 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1979 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1979 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1970s: Power to the Player Curt Flood’s sacrificial stand to win free agency opens the door for the biggest challenge yet to the reserve clause, which is eventually shattered—but not without fans suffering from numerous player strikes and holdouts.

The 1970s: Power to the Player Curt Flood’s sacrificial stand to win free agency opens the door for the biggest challenge yet to the reserve clause, which is eventually shattered—but not without fans suffering from numerous player strikes and holdouts.

The former pitcher and restaurateur talks of his playing days on the West Coast—and those afterward, when there was rarely a dull moment.

The former pitcher and restaurateur talks of his playing days on the West Coast—and those afterward, when there was rarely a dull moment.