THE YEARLY READER

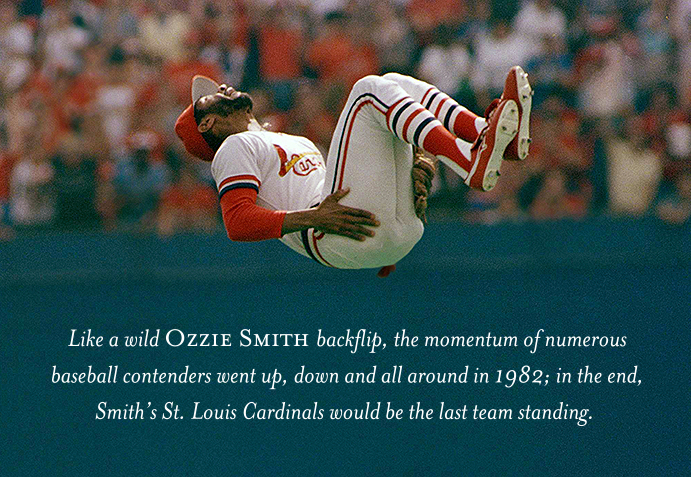

1982: Streaking Engagement

In a year of of rollercoaster pennant races, series comebacks and nail-biting finishes, the St. Louis Cardinals get the last say in a seven-game World Series against the high-powered Milwaukee Brewers.

(Associated Press)

They were everywhere in 1982, from start to finish. They set the tone and ruined the rhythm. They created pennant races and ended others. Some were long enough to set records, others short but no less pivotal.

Streaks, both of the winning and losing variety, were in abundant supply throughout the 1982 baseball season. Few teams were spared, ascending like contenders one moment, descending like pretenders the next—their fortunes careening about with all the elasticity of an out-of-control yo-yo.

No team experienced the ups and downs to such extremes as did the Atlanta Braves.

Though eventually self-promoted as “America’s Team,” the Braves entered 1982 as nobody’s team. On the field, they had done nothing for well over a decade, turned Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium into a ghost town with miniscule attendance, fielded a 43-year-old knuckleballer as their ace—and were, for the first time, being piloted by Joe Torre, whose naturally grim façade provided an accurate reflection of his previous five years managing the horrendous New York Mets.

All the ingredients for a potentially disastrous recipe would instead cook themselves into the pièce de résistance to start the major league season.

Blindsiding the baseball world, the Braves began the year by winning their first 13 games—breaking the all-time record for out-of-the-gate perfection set just a year earlier by Oakland. Then, like a dose of cold water, they lost five straight. Yet the Braves’ 13-0 start telegraphed to the National League’s Western Division that they were for real, televising the message into homes and bars across the country via the emerging cable landscape—with every Braves game broadcast coast-to-coast on Atlanta “superstation” WTBS, owned by eccentric Braves lord Ted Turner.

At first it seemed difficult to figure out the Braves’ success. There was good talent on the club, but it was virtually the same cast that had produced mediocrity in recent years. Yet one budding superstar fully flowered in 1982: Catcher-turned-outfielder Dale Murphy, a kindly, devout Mormon, stopped pulling the ball and started smacking it to all fields, with results (.281 average, 36 home runs, 109 runs batted in) which wounded opposing pitchers. On the mound, middle-aged knuckler Phil Niekro—who during the late 1970s tirelessly embraced working every fourth (sometimes third) day—was preserved within a rotation that was often set at five pitchers and produced one of his most efficient performances, winning 17 of 21 decisions.

The Braves settled into first place for the balance of the spring and were rediscovered by Atlanta sports fans—a group of folks notorious for flocking to see a winner while staying away en masse from losers. To make room, Turner told team mascot Chief Noc-A-Homa to pack up his teepee—which took up 250 seats’ worth of space behind the left field fence—and take his act elsewhere. The Chief apparently used the temporary platform to perform one last “paindance” upon Turner and his team.

The Braves immediately lost 11 straight.

Aggravating Atlanta’s losing streak were the subsequent winning streaks of divisional rivals in the defending champion Los Angeles Dodgers (eight straight wins) and the upstart San Francisco Giants (10 straight). Superstitious Braves fans pled with Turner to give the Chief his land back—Turner obliged—but by then the damage was done. The Braves had lost 19 of 21, and went from nine games up to four back behind the Dodgers.

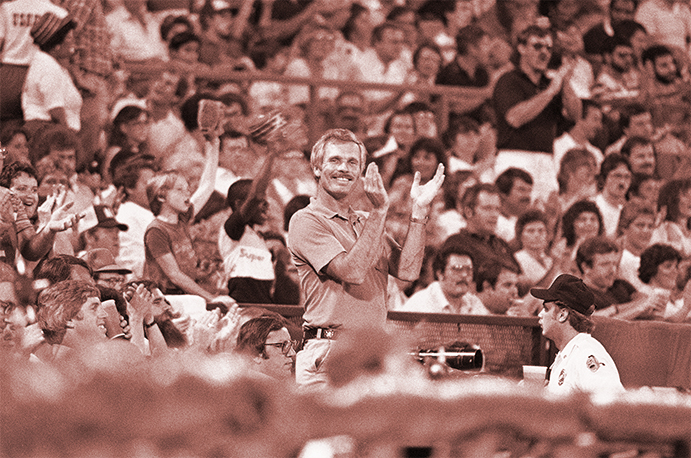

Standing out of the crowd to no one’s surprise, Atlanta owner Ted Turner leads the cheers for a Braves team that bolted out to a 13-0 start, giving them a critical boost toward its first postseason appearance in 13 years. (Associated Press)

From that sudden shakeup in August, the NL West would continue to violently teeter-totter towards season’s end. The Braves rebounded by winning six straight. The Giants lost six straight. The Dodgers stormed into September winning seven straight. Then they lost eight in a row. The Giants fired back up with two five-game win streaks. It became dizzying to keep track of the division, which began the season’s final week with only a game separating the Braves, Dodgers and Giants.

Atlanta started that last week with two crucial wins at San Francisco; the Dodgers then came to Candlestick Park and eliminated the Giants with two victories of their own. But as the Dodgers entered the last day a game behind Atlanta, the Giants weren’t done. Future Hall of Famer Joe Morgan, who at 39 was playing his second and last year at San Francisco, became a Giants hero for all time when his seventh-inning, three-run home run killed the Dodgers’ hopes, 5-3. For the Giants, it was sweet revenge against their archrival. For the Braves, it was their first NL West title in 13 years.

BTW: Morgan, who had not batted over .250 since 1977, had a renaissance campaign at San Francisco with a .289 average, 14 homers, 61 RBIs and 24 steals.

The NL’s Eastern Division was also not immune to streak-itis. For the St. Louis Cardinals, that would be a good thing.

Afflicted only with winning streaks, the Cardinals won 12 in a row in April to jump out to the early lead, and eight straight in early September to pull away from the competition for good. Their longest losing streak of the year, at four, came harmlessly after they clinched the division.

The architect of the 1982 Cardinals—a unit completely overhauled in less than two years—was Whitey Herzog, a blunt, no-nonsense character previously known for helping tool together the 1969 Miracle Mets, and for managing the Kansas City Royals to three straight divisional titles in the 1970s. Doubling as both manager and general manager at St. Louis, Herzog studied the fast and vast artificial expanses of Busch Stadium and knew he needed a roster that was speedy, agile and not full of individualism. Home runs would be considered a bonus.

Stepping down from the front office before Opening Day to concentrate on managing what he had assembled, Herzog fulfilled his vision; the Cardinals finished last in the NL in home runs, first in steals, and conquered the NL East.

Two first-year Cardinals named Smith fully confirmed the team’s dashing new style. Lonnie Smith, traded from the Philadelphia Phillies—a team strangely unable or unwilling to utilize his talents—showed what he could do as a full-timer by hitting .307 with 68 steals and a league-high 120 runs scored—numbers good enough to make him runner-up for NL Most Valuable Player honors. From San Diego came the other Smith: Ozzie. Highly sought after by Herzog, Smith was weak at the plate—hitting a powerless .248 in 1982—but at shortstop, he was nothing short of sensational, electrifying the Cardinals faithful with one acrobatic play after another. The fans fell in love with Ozzie and vice versa, beginning a wonderful relationship that would last through Smith’s retirement in 1996.

BTW: From 1980-81, the often-benched Lonnie Smith played the equivalent of one full season for the Phillies—batting .333 with 109 runs and 54 steals…Ozzie Smith created a far more pleasant state of affairs than his predecessor, Garry Templeton—who showed his love for St. Louis fans by flipping them off after being booed for his lackadaisical play.

The Cardinals were a tough enough opponent for the Atlanta Braves in the NLCS, but the weather also dealt the Braves a nasty hand. Heavy rains turned Game One into Game None at St. Louis, with just two outs standing between Atlanta starter Phil Niekro, leading 1-0, and the end of the fifth inning to make the game official. Having used their only formidable starter in a wasted effort, the called-off first game took the wind out of the Braves’ sails. Weather allowed the next three games to be played uninterrupted—and the Cardinals won them all, thanks mainly to stingy St. Louis pitching started by Bob Forsch (a three-hit shutout in the official Game One), continued with temperamental Dominican Joaquin Andujar (the Game Three winner) and closed by Bruce Sutter, who won Game Two in relief and saved the clincher.

Whitey Herzog had helped build one pennant winner in St. Louis. He inadvertently helped create another with his World Series opponent, the Milwaukee Brewers.

Born as the Seattle Pilots in 1969, the Brewers had impressively evolved through the late 1970s to become a potent, power-hitting threat good enough to field the American League East’s best record in the 1981 strike-shredded season. Two pitchers dealt away from the Cardinals had contributed: Starter Pete Vuckovich, with an AL-high 14 wins; and closer Rollie Fingers, earning the AL MVP and Cy Young Award with a stunning 1.04 earned run average.

But the Brewers began 1982 in a tense funk, and after a 23-24 start manager Buck Rodgers became the fall guy as players complained of his overly uptight attitude. In came Harvey Kuenn—the perennial .300 hitter and All-Star at Detroit during the 1950s, and Milwaukee’s batting coach since 1971—who discarded the tension with three simple words: “Let’s have fun.” Loosened up, the Brewers bombed away. They won 30 of their next 41 games thanks to a formidable offense with a voracious appetite for extra-base hits that quickly earned them the nickname, “Harvey’s Wallbangers.”

For the year, Milwaukee would rout an AL-high 216 balls over the fence, with a quintet of players each hitting at least 20—including catcher Ted Simmons, the other ex-Cardinal. Others leading Milwaukee’s hit parade included big boomer Gorman Thomas, with 39 homers; first baseman Cecil Cooper (.313 average, 32 homers, 121 RBIs), one of the game’s most unheralded hitters; third baseman Paul Molitor (.302, 19, 71), leading the AL with 136 runs; and shortstop Robin Yount, a starter at Milwaukee since age 18 who, eight years later, strengthened himself from just another lightweight infielder to a multi-purpose power threat. Yount’s 1982 numbers—a .331 average, 46 doubles, 12 triples, 29 homers and 114 RBIs—would easily earn him the AL MVP.

BTW: Those traded to St. Louis for Vuckovich, Fingers and Simmons included Sixto Lezcano, dealt to San Diego; David Green, who lost his job in 1982 to rookie Willie McGee; and pitcher Dave LaPoint, who gave the Cardinals a few decent years.

The Proof in Harvey’s Wallbangers

Before Harvey Kuenn took over as manager of the Brewers on June 2, the team’s hitting punch was modest at best. But the bats awoke and stayed hot all summer once Kuenn stepped up, translating to more wins—and an AL pennant.

On the mound, Vuckovich and Fingers continued to keep opponents from catching up. It was Vuckovich’s turn to earn the Cy with an 18-6 record and 3.34 ERA; Fingers saved 29 more games before an arm injury ended his season in early September.

Leading the AL East by four games with five to play—the last four at second-place Baltimore—the Brewers picked a fine time to get a case of the streaks; they lost four straight games, by a combined score of 35-11, to set up a winner-take-all affair against the Orioles on the regular season’s final day. The odds didn’t favor Milwaukee; the Orioles had won 9 of 13 on the year against the Brewers, fielded the division’s best home record, and were ready to start Jim Palmer—winner of 13 of his past 14 decisions after a tumultuous start that first landed him in manager Earl Weaver’s doghouse, then the bullpen, then briefly on the trading block. Adding to all of this was the emotional intangible of the tempestuous Weaver, who announced early in the year that he’d screamed enough at umpires and would retire at season’s end.

Apparently reminded with Kuenn’s thinking, the Brewers—and particularly Yount—unwound and had fun. They overpowered the Orioles, 10-2, taking their first-ever AL East title with Yount smashing two homers and a triple in triumph.

Streaks did not play a big factor in the AL West, where the high-powered, high-priced California Angels outlasted Kansas City by three games thanks to a collapse by the Royals’ pitching staff down the stretch. That was just fine with veteran Angels manager Gene Mauch, whose previous brush with famous streaks—losing 10 straight as manager of the 1964 Phillies to give away the NL pennant—made for some unpleasant memories.

Unfortunately for Mauch, more were on the way for the postseason.

A veteran team featuring 10 players with World Series experience—including Mr. October himself, Reggie Jackson, freed after five years with George Steinbrenner—the Angels put themselves in great shape at the ALCS by winning the first two games against Milwaukee. The Angels had three games to win one, but Mauch blew it again, in much the same way he blew it in 1964; by repeatedly using his best pitchers on short rest. Tommy John and Bruce Kison had gone the distance to win Games One and Two, respectively, but now they were asked to start Games Four and Five—if necessary—on three days rest. Both games were necessary, and they would both be lost; John was shelled in Game Four, and Kison only lasted five innings in the finale, replaced by a bullpen that couldn’t hold a slim 3-2 lead. The Brewers, despite hitting just .219 and committing eight errors against the Angels, moved upward.

BTW: Let go by the Yankees after hitting .237 in 1981, the 36-year-old Jackson slammed 39 home runs for the Angels to tie Gorman Thomas for the AL lead.

The St. Louis Cardinals got a brutal taste of Harvey’s Wallbangers to start the World Series by being blown out at home, 10-0; Paul Molitor’s five hits, all singles, was the first such accomplishment in World Series history. Whitey Herzog’s gang recovered to take the next two games, and then it was Milwaukee’s turn, taking Games Four and Five to reclaim the series lead. That brought the Series back to St. Louis, where Herzog needed the final two games to win it all. In this crazy year of titanic streaks and mood swings among baseball teams, how easy could it be to win two measly games in a row?

For the Cardinals, it was easy enough. They clobbered Milwaukee in Game Six, 13-1, then took the clincher when they bounced back from a two-run deficit in the sixth inning to topple the Brewers, 6-3.

Whitey Herzog would not be haunted by the three guys he’d sent out of St. Louis to flourish in Milwaukee. An injured Fingers never suited up, and without him the Brewers’ bullpen suffered with a 5.54 World Series ERA. Ted Simmons hit a few frivolous solo homers but overall batted just .174. Pete Vuckovich, who hadn’t won in a month since throwing 163 pitches in an extra-inning game, failed to win either of his two Series starts.

While the Brewers peaked with their 1982 performance—they would gradually settle into a mediocrity blamed on being a small-market team, if you listened to Milwaukee owner and future commissioner Bud Selig—the St. Louis triumph would trigger a comeback for one of baseball’s more historically respected organizations, following up one decade of rare forgettable play with a far more successful one.

Forward to 1983: The Good, the Old and the Ugly The Baltimore Orioles (good) fight off unlikely foes in the Philadelphia Phillies (old) and the Chicago White Sox (ugly).

Forward to 1983: The Good, the Old and the Ugly The Baltimore Orioles (good) fight off unlikely foes in the Philadelphia Phillies (old) and the Chicago White Sox (ugly).

Back to 1981: No Ball, One Strike A criplling midseason player strike plays havoc with the schedule and the integrity of playoff eligibility.

Back to 1981: No Ball, One Strike A criplling midseason player strike plays havoc with the schedule and the integrity of playoff eligibility.

1982 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1982 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1982 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1982 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1980s: Corporate Makeover Baseball enjoys a healthy boom on several fronts, with increased attendance, corporate sponsorship and memorabilia sales; players also continue to enjoy skyrocketing salaries, but some abuse their newfound riches by delving into illegal drugs.

The 1980s: Corporate Makeover Baseball enjoys a healthy boom on several fronts, with increased attendance, corporate sponsorship and memorabilia sales; players also continue to enjoy skyrocketing salaries, but some abuse their newfound riches by delving into illegal drugs.

Stefan Wever recalls his major league career that held tremendous promise—but ended up lasting one game.

Stefan Wever recalls his major league career that held tremendous promise—but ended up lasting one game.