THE YEARLY READER

2000: New York, New York

The New York Yankees make a bid to become baseball’s first three-peat champions in 25 years, but they must first accept the spirited challenge from their crosstown rivals in the Big Apple’s first exclusive World Series since the 1950s.

The Mets’ Mike Piazza is knocked out by a Roger Clemens fastball during a July interleague matchup with the Yankees; when the two teams reconvened for the World Series three months later, Clemens would hardly be in an apologetic mood. (Associated Press)

There was a time when the Subway Series seemed more rule than exception, when baseball’s Fall Classic would be determined solely within New York City’s borders. Thirteen such series would take place between 1921-57, from the time Babe Ruth first donned Yankee pinstripes to the moment the Giants and Dodgers turned their backs on the Big Apple and headed west.

Over the next 40 years, the Yankees and those new kids on the block, the Mets, would experience undulating periods of success, but they never caught one another at the top of the curve in an effort to revive the Subway Series.

That was, until 2000.

For much of the 1990s, the Yankees had re-established a virtual dominance over baseball, winning three of the last four World Series to close out the century. Meanwhile, the Mets were showing signs of catching up after sleepwalking through much of the decade.

The Mets’ parabolic upswing of recent years was anything but a smooth ride—especially for manager Bobby Valentine, whose playing career had long ago been cut short when he ran hard into an outfield wall. A year earlier, in 1999, Valentine’s managerial tenure at New York appeared to be headed for a similar fate after a 27-28. It was at that moment that the Mets’ management, in an almost Sicilian-style gesture, fired three of Valentine’s coaches. The message was as unmistakable as a dead fish delivered to Valentine’s desk: Start winning, or you’re next. An upbeat Valentine told everyone to judge him on the next 55 games, not the first 55. Valentine’s dare was met: The Mets won 40 of those next 55, nearly overtook the powerhouse Atlanta Braves in the National League East, qualified as a postseason wild card and got one more shot at the Braves in the NLCS—where they lost with their honor highly intact in an exhaustive six-game series.

For 2000, the Mets were salivating to continue their upward spiral as the burden of controversy shifted over to the Braves, thanks to a good ol’ Southern boy who closed out games for Atlanta with a wicked fastball—and opened his mouth with an equally wicked tongue.

John Rocker had already incurred the wrath of New Yorkers at the 1999 NLCS with a fiery brand of on-field antics and frequent verbal exchanges with Mets fans. Rather than respond with a good-natured slam of the Mets’ faithful, the boisterous, 25-year-old Rocker went after New York’s cultural diversity in a Sports Illustrated article that put baseball front-and-center in the dead of winter in a way it didn’t want.

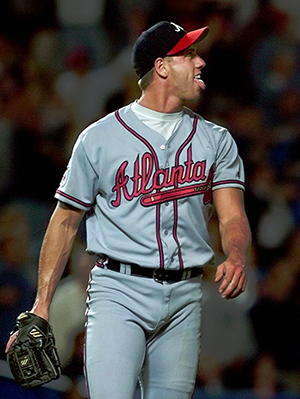

Flame-throwing Atlanta closer John Rocker became one against the world (his own teammates often included) for his on- and off-the-field antics—including his notorious, offensive diatribe against New Yorkers in a Sports Illustrated article. (Associated Press)

Rocker’s rant certainly bothered a lot of people, including commissioner Bud Selig—who wanted Rocker to see a psychiatrist before handing down a suspension that would cost the Atlanta closer the first month of the 2000 season. (The penalty would be reduced to two weeks by an independent arbitrator, at the urging of the players’ union.) Whatever advice or sensitivity training Rocker would get over the next six months didn’t seem to rub off on him. His apologies seemed forced, abrupt and insincere; he threatened Jeff Pearlman, who wrote the infamous Sports Illustrated article, when they bumped into one another at midseason; and Atlanta players tiring of Rocker began to publicly criticize him—an eye-opener, given the players’ usually tight-lipped solidarity for one another towards the press in regards to internal matters.

If the Rocker sideshow affected the Braves to start 2000, it never showed; the team finished April with a 15-game winning streak, the NL’s longest since 1951, to tear out in front of the Mets. When Rocker and the Braves visited Shea Stadium for the first time in late June under the watchful eyes of 50,000 angry fans and over 500 security officers, they split a four-game series and maintained their hold of first place.

BTW: Rocker pitched one inning in the series, retiring the side.

Fortunately for Rocker, Roger Clemens would take over as Public Enemy #1 among Mets fans a few weeks later.

Clemens’ second year with the Yankees had thus far been a frustrating experience in which injury and ineffectiveness had shared his headlines. Worse, he was getting the starting nod for the second game of a July 8 day-night doubleheader against the Mets and the explosive Mike Piazza—who not only owned Clemens (three homers among seven hits in just 12 lifetime at-bats), but also owned the whole NL to date with a .348 batting average, 24 homers and 72 runs batted in. Before the game, Clemens reportedly bragged to teammates that he would send Piazza a message by knocking him down.

BTW: The unique doubleheader featured the first game at Shea Stadium, the second at Yankee Stadium—the first twinbill split among different ballparks since 1903.

And when Piazza first came to the plate, that’s exactly what Clemens did. In the head.

Flattened, Piazza had to be helped off the field with a concussion; when his senses returned the next day, he refused to take a call of apology from Clemens, who claimed the knockdown was an accident. Others within the Mets’ organization surely thought otherwise, and their subtle vows of revenge, if anything else, certainly proved that interleague play had finally transcended its early days of cordial novelty.

BTW: In the Clemens-Piazza aftermath, Mets general manager Steve Phillips kicked Yankee players out of the Shea Stadium weight room and kept his players from sharing a chartered ride with Yankee All-Star Game participants.

Head Games

A year after struggling with a career-worst 4.60 ERA, Roger Clemens didn’t look any sharper to start 2000—until he nailed Mike Piazza in the head. Like a macabre wake-up call, the beaning seemed to fire up Clemens, who got his game back on track for the rest of the season (playoffs included).

Prior to the Piazza knockdown, the Yankees had been something of a first-half enigma, beaten up by injury and cursed by sub-standard play. Wandering with a record barely above .500 on the Fourth of July, the Yankees initiated a rash of midseason trading activity which was furious even by owner George Steinbrenner’s standards; the moves netted seven new players and helped right the Yankee ship back to high water, winning 44 of its 66 games. Two of the pick-ups proved crucial. David Justice came from Cleveland and, in roughly half a season’s work, hit .305 with 20 homers and 60 RBIs; and when talks to grab Sammy Sosa broke down, the Yankees settled for another Chicago outfielder in Glenallen Hill—who played like Sosa in New York, crushing 16 homers with 29 RBIs while batting .333 in just 40 games.

BTW: The Yankees even had the luxury of picking up Jose Canseco from Tampa—not with the intent to play him everyday, but to keep him from being signed by a contending rival.

The mid-year roster makeover helped New York win the AL East, but it couldn’t prevent the Yankees from falling down hard to end the regular season. If ever a team backed into the postseason, it was the 2000 Yankees. They lost 15 of their last 18 games—including their last seven by a combined score of 68-15. Even the lowly Tampa Bay Devil Rays knocked New York silly, outscoring the Yankees 24-5 in a three-game sweep. The two-time defending world champions pratfell into the playoffs with the worst record among all eight postseason participants.

Along with the Mets—returning to the playoffs as a wild card after once again falling short of Atlanta in the NL East—the two New York nines began their journey towards a possible Subway Series by first eliminating a possible Bay Bridge Series in the postseason’s first round. The Yankees re-awoke and relied on their veteran presence and tremendous postseason sage to outlast in the maximum five games the AL West-winning Oakland A’s, a hot young ballclub that was talented but badly inexperienced. Meanwhile, the Mets succeeded in their uphill NLDS challenge of unseating, in four games, the San Francisco Giants—owners of the majors’ best record at 97-65, and all but invincible at their gorgeous new waterfront digs, Pac Bell (now Oracle) Park.

Fully anticipating a NLCS rematch with current NL East rival Atlanta, the Mets were instead stunned to see past NL East nemesis and current NL Central champ St. Louis, who gave the Braves yet another premature exit from the postseason with a three-game NLDS sweep.

Even without the injured Mark McGwire, St. Louis wielded enough firepower with first-year Cardinals Jim Edmonds (.295 average, 42 home runs, 108 RBIs) and Will Clark, who filled in for McGwire by hitting .345 with 12 homers late in the year. But St. Louis pitching faltered against the Mets, while New York starter Mike Hampton threw 16 scoreless innings in winning the first and last games to give the Mets an unexpectedly easy, four-games-to-one triumph and their first NL flag since the franchise’s raucous 1986 campaign.

BTW: Despite his impressive performance at St. Louis, the 36-year-old Clark retired at the end of the year.

The Mets waited and hoped that they would get their long-awaited rebuttal at Roger Clemens. Roger Clemens would help take care of that.

The Yankees had found another formidable foe from the West for the ALCS in the Seattle Mariners; the AL wild card winners had just bumped off the league’s number one seed in the debilitated Chicago White Sox. With Randy Johnson and Ken Griffey Jr. long gone, the Mariners’ star of the moment was 25-year-old shortstop phenom Alex Rodriguez (.316 average, 41 home runs, 132 RBIs)—who himself was expected to jump ship at season’s end for the ultra-riches of free agency.

BTW: The White Sox’ three main starters—James Baldwin, Jim Parque and Mike Sirotka—all fell to major arm and shoulder injuries; Sirotka would never pitch again.

Down two games to one, the Mariners hoped to even the Yankees up in Game Four at Seattle—against Clemens. But the Rocket’s game, both in terms of performance and intimidation, was on fire. Rodriguez found this out, up close and personal—twice thrown at near the head in his first at-bat. It was vintage Clemens; he let the league’s best hitter know who was in charge, all while firing a one-hit shutout, pushing the Yankees to within a game of an AL title they would ultimately take in six games.

Rodriguez, like most other Mariners, was 0-for-3 against Clemens. For the rest of the ALCS, he was 9-for-19 with a pair of homers.

BTW: The usually congenial Rodriguez admitted that he was a “little pissed off” about Clemens’ dustings.

The Yankees and Mets readied for the first Subway Series since 1956, but provincial bragging rights took a back seat to the bigger buzz: Roger Clemens vs. Mike Piazza, Round 2. What was going to happen? Would anything happen?

Though Clemens was rested and ready to pitch the opener, Yankees skipper Joe Torre knew the politics of vengeance all too well. He gave Clemens the starting assignments for Games Two and Six for one simple reason: They would both be played at Yankee Stadium. Starting him in Games One and Five meant he would have to pitch the latter at Shea Stadium, where Clemens couldn’t hide behind the designated hitter. He’d have to hit and perhaps learn—in front of 50,000 very hostile fans that John Rocker could tell you about—how Mike Piazza felt when he was on his back, dazed and confused.

Roger Clemens claimed to believe that the jagged end of Mike Piazza’s bat was a foul ball he was lobbing back toward the on-deck circle. His intense wind-up and fiery expression clearly suggests otherwise. (Associated Press)

After the Yankees won Game One, 4-3, in a come-from-behind, 12-inning affair, Clemens took the mound for Game Two—and wasted no time getting into Piazza’s head without firing a fastball near it. On the fourth pitch of his first at-bat, Piazza hit a broken-bat dribbler up the first base line; instinctively, he ran towards first base before the ball went foul, while half of the bat headed toward Clemens. Jumping off the mound, Clemens picked up the remnant, jagged end and all, and fired it at Piazza’s feet. Calm but obviously perturbed, Piazza approached Clemens with his hands outstretched while Clemens basically ignored him, asking the umpire for a new ball. Both benches emptied, but nothing or no one erupted.

Clemens’ latest bizarre bully tactic once more seemed to get the worst of the opposition. He pitched eight nearly flawless shutout innings, allowing only two hits while striking out nine. He left with a 6-0 lead, which the normally reliable Yankees bullpen nearly lost as they barely held off a furious ninth-inning Mets rally to survive, 6-5.

Piazza, like most other Mets, went 0-for-3 against Clemens. For the rest of the World Series, he was 6-for-19 with a pair of homers.

BTW: The usually congenial Piazza, on Clemens afterward: “He had no response. He didn’t say anything. It was bizarre.”

Sweet Fourteen

By winning the first two games of the 2000 Fall Classic, the Yankees set a record with 14 consecutive World Series victories—topping the 12 achieved in back-to-back-to-back sweeps by the 1927, 1928 and 1932 Yankees. As one might guess, it took a total team effort to go 14-0.

Never one to give credible interpretations of events, Clemens said afterward that he initially mistook Piazza’s severed bat for the ball, and then tried to lob it towards the on-deck circle—though the hostile nature of Clemens’ “lob” right towards Piazza brought that theory into question. The commissioner’s office certainly didn’t buy it and fined Clemens $50,000. Clemens otherwise shut his mouth, knowing the Mets might seek revenge if he had to return and start Game Six.

The Mets couldn’t take it that far.

In Game Three, the Mets finally secured a 4-2 victory—snapping the Yankees’ 14-game World Series win streak in the process—but it was a solitary moment of success in a series otherwise dictated—but not dominated—by the Yankees. Derek Jeter homered off Mets starter Bobby Jones on the first pitch of Game Four, and the Yankees held off another Mets rally to win, 3-2; in Game Five, the Yankees wrapped it up when they rallied for two runs in the bottom of the eighth off the Mets’ Al Leiter—who labored through 140 pitches trying to keep the series alive—to take a 4-2 lead that Mariano Rivera closed out in the ninth.

BTW: The Game Five loss gave Leiter a career 0-3 record in 11 postseason starts through 2000.

Being the first team since the 1972-74 Oakland A’s to perform a World Series three-peat was all the more sweet for the Yankees, given the relatively lackluster regular season they had survived. The ticker-tape parade through Manhattan would once again belong to the Yankees, reveling in a proud city’s celebration of a dream year.

One year later, the Yankees would be called upon to help pull New York City out of a horrifying nightmare.

Forward to 2001: Raising Arizona The fourth-year Arizona Diamondbacks’ expensive fast track to the World Series reaches a successful conclusion.

Forward to 2001: Raising Arizona The fourth-year Arizona Diamondbacks’ expensive fast track to the World Series reaches a successful conclusion.

Back to 1999: The Umpires Strike Out Major league umpires implode with a foolhardy strategy following a series of run-ins with players and executives.

Back to 1999: The Umpires Strike Out Major league umpires implode with a foolhardy strategy following a series of run-ins with players and executives.

2000 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 2000 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

2000 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 2000 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 2000s: Driven Deep to Disgrace The new century gives Major League Baseball a decidedly more international flavor with a healthy rise in foreign-born talent—but a disturbing pall is cast over the sport as one megastar after another is exposed for using steroids.

The 2000s: Driven Deep to Disgrace The new century gives Major League Baseball a decidedly more international flavor with a healthy rise in foreign-born talent—but a disturbing pall is cast over the sport as one megastar after another is exposed for using steroids.

Part of a surprisingly good (but ultimately fragile) White Sox rotation in 2000, Jim Parque looks back on his baseball upbringing, his contribution to a particularly nasty brawl and his appearnce in the Mitchell Report.

Part of a surprisingly good (but ultimately fragile) White Sox rotation in 2000, Jim Parque looks back on his baseball upbringing, his contribution to a particularly nasty brawl and his appearnce in the Mitchell Report.