The Ballparks

The 1990s-2010s: Coming Home

Oriole Park at Camden Yards opens the door for a new wave of ballpark construction as teams return to their roots and embrace yesteryear with a clever eye toward massive revenues.

Baltimore’s Oriole Park at Camden Yards hit it out of the park with its ode to old-fashioned ballparks, most famously with its inclusion of the B&O Warehouse behind right field to give it the perfect old-time touch. It also scored a goldmine of revenue for the Orioles, forcing other teams to sit up and take notice. (Flickr—Keith Allison)

By the 1980s, America quickly concluded that the starry-eyed future it had imagined a generation earlier never materialized. Instead of social progress, flying cars and near-utopian communities, the nation became hobbled by Watergate, Vietnam, oil/energy shortages, the onset of modern terrorism and the overall disintegration of trust toward government and corporations. Americans—and baseball fans in particular—wanted badly to go back to a place author Tom Wolfe once said they couldn’t: Home.

Baseball’s future was now focused toward yesteryear. Fenway Park, Wrigley Field and the other surviving warhorses of the steel-and-concrete era, maligned and threatened with extinction 20 years earlier, were back in vogue as fans discovered a nostalgic appreciation for the innocence the older parks once represented, and the warm welcome they continued to retain. The more recent multi-purpose stadia, meanwhile, branched out for some of the old-time charm; they installed hand-operated scoreboards, chucked the fake turf in favor of real grass and in a few places went asymmetrical because, hey, that’s the way it used to be.

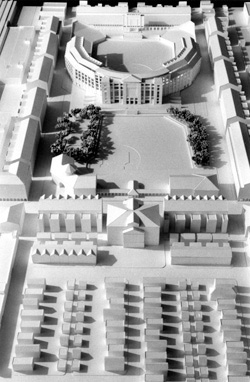

In 1986, the Society for American Baseball Research (SABR) sponsored a proposal by Chicago architect Philip Bess to design a new ballpark as an alternative course of action for the White Sox, who wanted to replace Comiskey Park and threatened a move to Florida as a means of getting their wish. Bess’ vision was Armour Field, a block-constrained ballpark at the center of a mixed-use neighborhood that included residences, retail shops and a park, all anchored by a 42,000-seat throwback ballpark complete with stunning views of the Chicago skyline. It was a modern take on the steel-and-concrete venues; rich in character, interactive within its surrounding environs.

This is as close to reality as Armour Field, a mixed-use ballpark community, would come in Chicago while the White Sox propped up a new (and much chastised) version of Comiskey Park. But Philip Bess’ inspirations would not be forgotten by ballpark architects and the teams that hired them. (Image courtesy of Philip Bess)

The Armour Field concept may have been lost on the White Sox, but not on Kansas City-based HOK Sport, the architect of New Comiskey. HOK had, a few years earlier, been thinking on the same wavelength as Bess when it designed Pilot Field, an 18,000-seat minor league facility in Buffalo. Though it lacked some of the purer mixed-use qualities of Armour Field, Pilot Field borrowed heavily from the past—opening the outfield to reveal downtown Buffalo, forging asymmetrical field dimensions and various outfield wall heights, and presenting itself on the outside with architectural touches similar to what one would have once saw standing in front of Ebbets Field or Forbes Field.

Pilot Field was a local smash but barely created a ripple nationally—yet HOK knew it had caught onto something seminal. Its intuition paid off in 1992 when its latest vision, Camden Yards at Oriole Park, opened in Baltimore. Everything about it seemed to be just right—including the timing for baseball fans starving for a return to more wistful times. There were cozy sightlines, upscale amenities and other modern-day wrinkles, but HOK nailed it by leaving the abandoned B&O Warehouse, a massively long, eight-story brick structure, behind right field when the initial thought was to tear it down. The building was the perfect touch of antiquity for Oriole Park, which became an instant classic and the talk of baseball.

For the game’s owners, Oriole Park’s aesthetics were fine and dandy, but they were focused on the three million-plus fans the Orioles annually drew to their new ballpark, the revenue the team scooped up and the competitive advantage they acquired as a result. In the wake of Oriole Park’s success, baseball’s new golden age of ballparks had arrived. The stampede was on.

Over the next 20 years, 20 new ballparks would be constructed, almost all of them designed by HOK (now called Populous) using the Oriole Park template to recapture an inner-city vibe that itself was back in style, as a new generation of wealth dared to return from the suburbs and pump life into previously derelict sections of the city. The process worked, with whole urban districts coming alive with chic townhouses, brewpubs, restaurants and trendy retail magnetized to the ballpark, the mothership. It wasn’t exactly the interactive, mixed-use blueprint Philip Bess had envisioned with Armour Field back in Chicago, but many of these new ballparks still managed to stimulate an energetic sense of community around them.

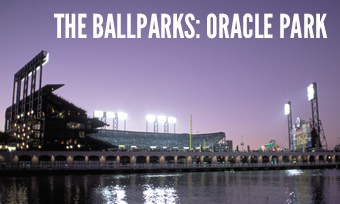

In sharp contrast to the sterile redundancy that the multi-purpose stadiums of the 1960s-1970s offered, the retro ballparks came with their own signature sights that set them apart from one another. There were the splash hits in McCovey Cove beyond San Francisco’s AT&T Park, the towering Pittsburgh skyline clearly visible from PNC Park, the swimming pool behind Chase Field’s outfield fence in Phoenix, the Western Metal building at San Diego’s Petco Park and the home run sculpture at Miami’s Marlins Park. The 21st-Century clone of Yankee Stadium even brought back the famed upper-deck frieze that had been a trademark of the 1920s original before being relegated to the bleachers during its bland 1970s makeover.

Fans at the new ballparks sat closer to the field than ever before, and at angles more appropriately directed toward the action. Tickets prices rose with increased demand for seats (to say nothing of the ever-rising salaries of ballplayers), but baseball remained the better bargain relative to the other major team sports, with some seats still to be had for less than 10 bucks on occasion. And because a return to the urban setting meant a return to various mass transit options—in some cases right up to the ballparks’ front doors—a hefty parking tab could also be avoided.

The teams loved the new ballparks as much as their fans, and for good reason; in many cases, the teams got their cake and ate it too as they paid little for the facilities while pocketing all the revenue. Everything seemed to have a corporate sponsor attached to it, from the ballpark name to the beer garden to the foul pole.

How did major league teams snag these sweetheart deals? The story often went like this: Team comes to city council and says, “We’d like a new ballpark and, oh, please help pay for it. In fact, pay for most of it. If you don’t, maybe we’ll go somewhere else. St. Petersburg sounds nice. Or maybe San Antonio, or Vegas, or Charlotte.” The politicians, under pressure from rabid fans who would villainize them forever if the team carried through on its threat, gave in, sometimes with—and sometimes without—the help of a public vote that often produced slim margins of approval. Even then, the easy part was not over for the politicians; they would start to hear it from the rabid non-fans—like the disgruntled, anti-ballpark citizen in Phoenix whose idea of rebuttal was to shoot and wound a county supervisor who green-lighted the new venue for the Arizona Diamondbacks.

More than not, the public chipped in with well over half of the financing for the ballparks. Going Dutch would not be found in places like Washington, where Nationals Park’s $610 million tab was totally covered by D.C. residents—or in Pittsburgh and Cincinnati, where the piecemeal contributions of the Pirates and Reds would be offset by revenue earned from naming rights given to, respectively, PNC Bank and Great American Insurance Group. Only two ballparks received no public financing: Atlanta’s Turner Field (thank you, 1996 Summer Olympics) and San Francisco’s AT&T Park (thank you, Giants). The other 18 new parks totaled $4.4 billion in up-front public financing—a figure that was sure to mushroom when the bills came due on the interest. Just ask the citizens of Florida’s Dade County, who alone will have to fork out $2.5 billion over 40 years to pay off construction bonds on Miami’s Marlins Park.

Above the ugly political underneath, the fans focused on the final product and loved it. They loved the quirks, the unexpected ricochets off the asymmetrical walls and all the frills that modern big league baseball provided thanks in large part to the game’s golden palaces. In 2007, the retro movement peaked with record average attendance at 32,700 as 10 teams clicked over three million fans through the turnstiles. When Oriole Park at Camden Yards opened in 1992, total MLB revenue checked in at $1.2 billion; 20 years and 20 new ballparks later, it had ballooned six-fold to under $8 billion. Part of that was attributable to increased national and local TV income as well as MLB’s newly-created Advanced Media arm, but it was naïve to think that this unparalleled influx of wealth had little to do with baseball’s grandest ballpark boom yet.

Forward to The Future: The Shape of Ballparks to Come Now that the retro ballpark boom has run its course, what do major league teams and architects have in mind for the next era of new facilities? Here’s a few hints of what might be ahead.

Forward to The Future: The Shape of Ballparks to Come Now that the retro ballpark boom has run its course, what do major league teams and architects have in mind for the next era of new facilities? Here’s a few hints of what might be ahead.

Back to the 1960s-1980s: The Cookie Cutter Monsters Multi-purpose stadiums become the rage as a line of enclosed facilities adaptable to disparate events welcome in baseball teams fleeing decaying ballparks and inner cities.

Back to the 1960s-1980s: The Cookie Cutter Monsters Multi-purpose stadiums become the rage as a line of enclosed facilities adaptable to disparate events welcome in baseball teams fleeing decaying ballparks and inner cities.