THE YEARLY READER

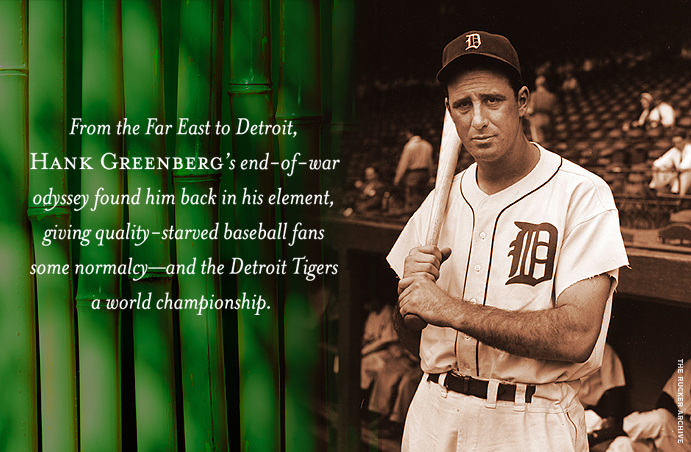

1945: Hank’s Heroic Rescue

With war coming to a victorious end, star players begin to filter back to the majors—including Hank Greenberg, whose presence in the season’s second half lifts Detroit to a World Series triumph over the Chicago Cubs.

China was about as far away as Hank Greenberg could be from a major league ballpark, but there he was, serving desk duty for the Allies late in 1944.

Back in 1941, the Detroit Tigers slugger was among the first of the major leaguers to be drafted into the military, plucked away before America entered the Second World War. Justifiably, Greenberg became the first big-name major leaguer to return to baseball when he was given back his civilian life in June. Immediately, he would reclaim his lofty standing among the game’s elite—what little of it was left on the field for the moment—and helped elevate the Tigers to thrilling triumphs in both the American League pennant race and the World Series that followed.

As much as Greenberg needed baseball, baseball needed Greenberg—badly. His homecoming, along with those of a precious few other genuine superstars, salvaged a major league campaign many considered lucky to be played at all.

With hopes for a wintertime ending to war in Europe being dashed from intense German resistance at the Battle of the Bulge, Americans back home saw wartime restrictions tightening, not loosening, up. Horse racing had just been shut down for the duration of the war, and Washington was considering a “work or fight” order—an edict not unlike the one that nearly silenced baseball during World War I.

More than ever, ballplayers were being called away for service, and there was increased pressure to take a second look at 4Fs, draft-ineligible men who were making up the majority of what remained on major league rosters.

As pressure and criticism mounted upon them, major league owners feared for the first time since FDR’s “Green Light Letter” four years earlier that baseball would have to be closed down indefinitely.

Spring arrived with better news from the European front, so baseball felt more at ease to march ahead with its 1945 schedule. But forced to dig ever deeper into the talent scrap heap, some wondered why the majors even bothered.

Stars of yesteryear continued to make their presence felt. Babe Herman, Guy Bush and Hod Lisenbee—all of whom had played their best baseball during the 1920s—came out of retirement to make small contributions during the season. Paul Schrieber, a 42-year-old batting practice pitcher for the New York Yankees, decided to work some relief for the team late in the year—his first major league action since 1923. And in Boston, playing at the age of 45 was something that the Braves’ Joe Heving could tell his grandson about. In fact, Heving could tell him then; the kid was already three years old.

The Height of Servitude

Although Allied victory was academic and major leaguers began returning to the ballpark from military service, 1945 represented the peak in terms of active players drafted or enlisted within the armed forces.

That teams survived with handicapped rosters was, in some cases, no exaggeration. A year after losing his leg in a plane crash in Germany, Bert Shepard appeared in a Washington uniform and tossed five innings for the Senators with a wooden peg in place of the leg he lost.

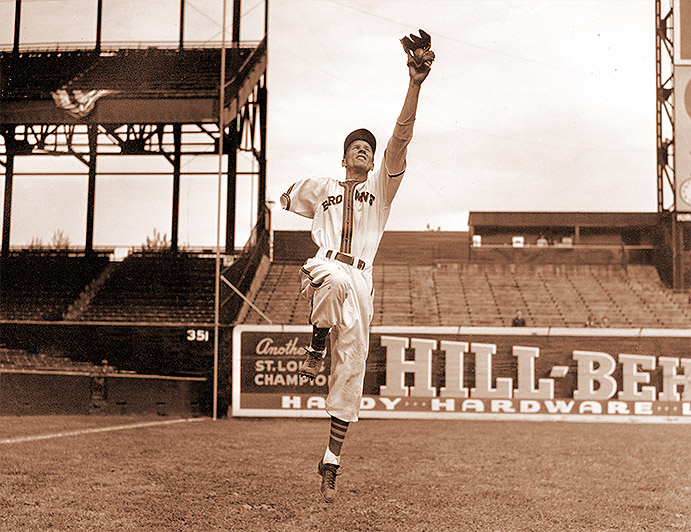

But it was the defending AL champion St. Louis Browns who made the loudest noise when they signed Pete Gray—a one-armed outfielder.

Gray was no publicity stunt; he batted .333 as a minor leaguer in 1944 and earned the American Association’s Most Valuable Player award. Facing off against major league pitching—as mediocre as it had become—was a much tougher chore for Gray at St. Louis, batting .218 with no home runs in 77 games. Worse, his handicap made his ability to field a ball and throw it back to the infield more time-consuming, making it easier for opposing baserunners to stretch for an extra base. Gray’s Browns teammates turned red, believing his defensive deficiencies cost them a shot at a second straight AL flag.

BTW: The Browns finished in third place, six games back; their 81-70 performance would be the franchise’s last over the .500 mark until 1960, six years after the team moved to Baltimore.

Pete Gray was the most celebrated of baseball’s wartime replacement players, hitting .218 as a one-armed outfielder for the St. Louis Browns in 1945. (Associated Press)

One casualty of the 1945 baseball season was the All-Star Game, canceled due to travel restrictions and, perhaps more pointedly, because there were few available ballplayers worthy of being All-Stars.

That slowly began to change in the season’s second half.

With the war in Europe over and the atomic bomb about to drop on Japan, name players began to slowly filter back into major league uniforms, bringing a big-time sigh of relief from quality-starved baseball fans. Bob Feller, the game’s best pitcher before America entered the war, picked up where he left off for the Cleveland Indians in August when he won his first of nine starts—over Greenberg and the Tigers. Even more impressive was the return of Dick Fowler, who three years earlier was a promising prospect for the Philadelphia A’s. Denied the chance to mature on the mound when the Canadian Army came calling, Fowler finally got back to Philadelphia late in 1945—and fired a no-hitter against the Browns in his first start. Elsewhere, other familiar faces were back in the fold, including Charlie Keller, Luke Appling, Red Ruffing and Cecil Travis.

BTW: Dick Fowler’s no-hitter was the American League’s first since 1940.

But nobody had a finer re-entry into baseball in 1945 than Hank Greenberg.

Unlike other ballplayers serving their country, Greenberg rarely got the chance to keep his baseball skills sharp by playing military pick-up ball. But proving that natural ability counted for something—even at the age of 34—Greenberg re-emerged on the major league scene in July as if he hadn’t skipped a beat, homering off the A’s in his first game back before 48,000 Detroit fans that had welcomed him home.

The Tigers, up by a game and a half in the AL race at that moment, became more prominently powered by Greenberg’s presence. Their main competitor throughout the summer would be the Washington Senators, making a run to become baseball’s first worst-to-first team—if anything else, a reflection of wartime baseball’s constant shifting of power and the teams’ forced reinvention of themselves every season. Like Greenberg in Detroit, the Senators had their own discharged star, outfielder Buddy Lewis, coming to the rescue. Playing the second half of the season, Lewis batted .333 and helped balance out a Senators roster already blessed with three strong knuckleball pitchers—Roger Wolff, Dutch Leonard, and Mickey Haefner—all classified as 4F.

The Senators might have played stronger at the finish, but were forced into a series of doubleheaders to end the season a week before everyone else so that owner Clark Griffith could loan his ballpark out to the NFL’s Washington Redskins. When they lost their final game—thanks in part to a dropped fly ball by outfielder Bingo Binks, a partially deaf, 4F player wrapping up the only full-time season he would ever know in the majors—it left the Tigers, who still had four games to play, a game in front.

Detroit split a doubleheader with Cleveland, then had to sit through three days of rain at St. Louis before finally taking the field for a final twinbill against the Browns, needing one to win.

Despite good pitching by Virgil Trucks and Hal Newhouser—the latter on his way to a second straight AL MVP—the Tigers trailed in the first game by a run going to the top of the ninth inning. Browns starter Nels Potter got into trouble by letting two runners get into scoring position—but he really started to play with fire when he intentionally walked 40-year-old Doc Cramer. The free pass set up a force at any base for the next batter: Hank Greenberg.

Potter would get burned. Greenberg launched a drive that barely stayed fair down the left field line, resulting in a game-winning—and pennant-clinching—grand slam. Detroit’s 6-3 victory made the second game, canceled by rain, a moot point.

Through his half-season of reacquaintance, Greenberg batted a team-high .311 while hammering 13 home runs with 60 runs batted in—third on the Tigers behind Rudy York, his old powermate who was one of baseball’s few stars never to spend a day in the military during the war, and Roy Cullenbine, a critical early-season pick-up from Cleveland.

It took some time, but the draft finally caught up with the St. Louis Cardinals. Key players gone from the 1945 edition of the Redbirds were catcher Walker Cooper, pitcher Max Lanier and, most crippling of all, Stan Musial. These painful losses, though not enough to send the Cardinal nest into freefall, stripped the club of its National League dominance.

The Chicago Cubs would become the benefactors.

It would be the second NL pennant at Chicago for manager Charlie Grimm, enjoying his second tour of duty as the Cubs’ manager. Grimm won thanks to the team’s mastery of the doubleheader, sweeping a record 20 twinbills while being swept only three times; won with a solid pitching rotation led by 22-game winner Hank Wyse and aging veterans in Claude Passeau (36) and Paul Derringer and Ray Prim (both 38); and won despite a power outage from outfielder Bill Nicholson, suffering from diabetes after being the league’s premier slugger each of the previous two seasons.

BTW: Ray Prim, rediscovered by the majors in 1943 after an eight-year absence, led NL pitchers with a 2.40 ERA.

The Cubs also benefited from the generous mid-season acquisition of pitcher Hank Borowy. Though he had emerged as a legitimate staff ace for the wartime Yankees, the New York front office felt that Borowy was not a solid hurler down the stretch and sold him to the Cubs for $100,000—a move that so irked Yankees manager Joe McCarthy, it began a falling out that resulted in his departure from the team a year later.

Borowy’s half-season stint at Chicago proved McCarthy right, Yankees management wrong. He won 11 games for the Cubs—including four against St. Louis, a pivotal fact given Chicago’s three-game finish over the Cardinals.

Splitting the Score

Hank Borowy’s 21 combined wins between the Yankees and Cubs made him only one of six major leaguers to win at least 20 in one season split among teams in different leagues. Along with Bartolo Colon, Borowy managed to win 10 or more games with each team.

A colorful seven-game World Series would nonetheless go down as one of the worst ever played, an appropriate swan song to the misery of wartime baseball. Mental blunders were prevalent throughout the Series, committed mostly by the elders who, had it not been for war, were more likely to have been spectators in the stands.

Though a close series, none of the games went to the wire except for a sloppy Game Six, won by the Cubs in 12 innings thanks to a spirited relief effort by Hank Borowy—a mere one day after a lifeless start of five-plus innings. Just two more days later, Borowy—by now the Cubs’ workhorse—was overtaxed into starting Game Seven, allowing base hits to the first three batters before being removed. Detroit ran away with a 9-3 clincher.

The Tigers managed to capture their second-ever championship despite a .223 team batting average and just two home runs—both hit by Greenberg, who also smacked three doubles, drove in seven runs and safely reached base 13 times during the Series.

Hank Greenberg scores on a force play, the third run scored in a four-run fourth inning in Game Four of the World Series that brought the Tigers even with the Cubs; Detroit would win it in seven games. (The Rucker Archive)

A trivial subplot came out of the World Series that would develop into historic folklore. Before Game Four, A local Chicago tavern owner named William Sianis came to Wrigley Field with a ticket in hand and his pet billy goat at his side. The Cubs ticket takers said yes to Sianis, no to the billy goat. An enraged Sianis left, allegedly barking as he stormed off, “Cubs, they not gonna win anymore.”

A curse was born. The Cubs, up two games to one at the time, lost three of their next four to drop the Series, their seventh straight defeat at the Fall Classic.

It would be seven whole decades before they’d return.

BTW: Sianis was the inspiration for the memorable Greek restaurant skits (“Cheeseburger! Cheeseburger!”) performed on Saturday Night Live during the 1970s.

Forward to 1946: It’s Good to be Home The players are back and so are the fans, as attendance booms in baseball’s first postwar campaign.

Forward to 1946: It’s Good to be Home The players are back and so are the fans, as attendance booms in baseball’s first postwar campaign.

Back to 1944: Meet Us in St. Louis The powerhouse St. Louis Cardinals get a surprise World Series opponent in the neighboring Browns.

Back to 1944: Meet Us in St. Louis The powerhouse St. Louis Cardinals get a surprise World Series opponent in the neighboring Browns.

1945 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1945 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1945 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1945 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1940s: Of Rations and Spoils The return to a healthy economy and the breaking of the color barrier helps baseball reach an explosive new level of popularity—but not before enduring with America the hardship and sacrifice of World War II.

The 1940s: Of Rations and Spoils The return to a healthy economy and the breaking of the color barrier helps baseball reach an explosive new level of popularity—but not before enduring with America the hardship and sacrifice of World War II.

The last surviving member of the last Chicago Cubs team to reach the World Series, Lennie Merullo recalls getting tips from Babe Ruth and an awful first inning on the day his first son was born.

The last surviving member of the last Chicago Cubs team to reach the World Series, Lennie Merullo recalls getting tips from Babe Ruth and an awful first inning on the day his first son was born. Ray Hathaway, one of many major leaguers active only during World War II, talks of Leo Durocher, Branch Rickey, Jackie Robinson and his one year in Brooklyn.

Ray Hathaway, one of many major leaguers active only during World War II, talks of Leo Durocher, Branch Rickey, Jackie Robinson and his one year in Brooklyn. Hobie Landrith recalls his teen years helping Hank Greenberg get back into baseball shape after his return from service in World War II.

Hobie Landrith recalls his teen years helping Hank Greenberg get back into baseball shape after his return from service in World War II.