THE YEARLY READER

1955: Next Year at Last

After losing in seven previous World Series appearances—the last five to the New York Yankees—the Brooklyn Dodgers finally get the better of the Fall Classic against their crosstown rivals.

(Associated Press)

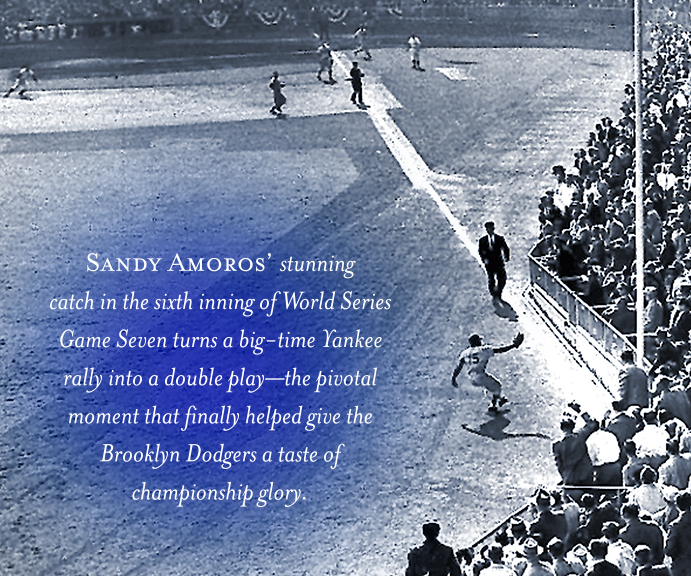

Game Seven, 1955 World Series, Yankee Stadium. The Brooklyn Dodgers, watching Yogi Berra’s fly ball dropping quickly towards the left-field corner, were getting that sinking feeling of déjà vu all over again, as Berra himself would famously state.

Berra’s drive wasn’t slowing down to show sympathy for anyone in a Dodger uniform—certainly not left fielder Sandy Amoros, the 23-year-old Cuban who was positioned well into left-center, expecting Berra to do anything but pull the ball down the line. As Amoros sprinted in for what seemed a futile attempt to catch it, Gil McDougald, representing the tying run at first base for the Yankees, started chugging towards third convinced, as everyone else, that the ball would drop and ignite a late-inning Yankee comeback.

Implausible as it seemed at that moment, fate was about to finally side with Dodger Blue.

The Dodgers were in embarrassing company with the historically inept St. Louis Browns and Philadelphia Phillies as the three teams yet to win a World Series. Unlike those two other misfits, the Dodgers had their chances. Lots of them.

This is the franchise that had been to seven previous World Series, and lost them all. This is the franchise that lost three heart-breaking tiebreakers in the past nine years just trying to get to the Series. This is the franchise that ended up on the wrong side of Bill Wambsganss’ unassisted triple play in 1920, Mickey Owen’s passed ball in 1941, Game Seven results to the New York Yankees in the 1947 and 1952 Series, and Bobby Thomson’s Shot Heard ’Round the World in 1951. With each sensational near miss, the Dodgers became more celebrated as baseball’s eternal bridesmaids. In the borough of Brooklyn, the cry at the end of every season was as painful as it was deafening: “Wait ’til next year.”

Next year, defined as 1955 by Dodgers fans after another second-place finish in 1954, didn’t hold a lot of promise to start with. The team’s collection of All-Star hitters, though still highly potent, was beginning to age. The pitching staff was younger, but opponents weren’t intimidated with what it had to offer in recent years. An exception was Karl Spooner, a phenom who sensationally teased Dodgers fans with two shutouts and 27 total strikeouts in two starting assignments at the end of 1954; but his pitching arm developed “severe tendinitis” in spring training and his potential was forever snuffed. Another hot prospect, a 19-year-old lefty named Sandy Koufax, was too unrefined as yet to make an impact.

BTW: The tendinitis was, in fact, the dreaded rotator cuff injury; Spooner never pitched in the majors after 1955.

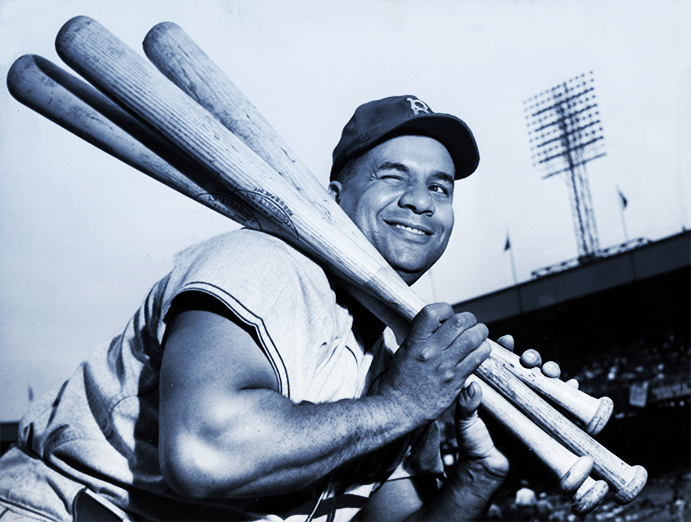

Four bats, a wink and a nod: Powerful Brooklyn catcher Roy Campanella shows an appropriately content look in the midst of his third MVP season over a five-year period, hitting .318 with 32 home runs and 107 RBIs in just 123 games. (The Rucker Archive)

More problematic for the Dodgers was the tension surrounding second-year manager Walter Alston. A virtual unknown when Brooklyn owner Walter O’Malley hired him the year before, Alston’s résumé was as humble as his personality—managing his way up through the Dodgers minor league system—and that encouraged the team’s star veterans, especially Jackie Robinson, to challenge his authority. After all, what did Alston know as a player? His previous major league experience consisted of a single game with the St. Louis Cardinals in 1936, striking out in his only at-bat while making an error in two chances playing first base.

BTW: Alston replaced Charley Dressen, fired by O’Malley when he demanded a multi-year contract.

A sizeable man balanced with a tranquil demeanor, Alston made for an impressive debut in 1954, all things considered. Brooklyn won 92 games despite Alston’s strained relationship with his players, an anemic pitching staff and defective output from two of its stars: Pitcher Don Newcombe (nine wins, eight losses, and a 4.56 earned run average) and catcher Roy Campanella (.207 batting average, 19 home runs).

If Alston was looking for a cure to win over his players, he got it in the form of 10 straight wins to open the 1955 season—the first major league team ever to accomplish such a task. After finally losing, the Dodgers went on to win 10 of their next 11 to improve to 22-2. With a 10-game lead by July, the Dodgers never wavered as they became the first team since the famed 1927 Yankees to hold first place from the season’s first day to its last. With three weeks to spare, Brooklyn clinched its sixth NL pennant in 15 years—and reserved yet another shot at smashing the stigma of second best at the World Series.

Campanella and Newcombe, the two Dodgers so horribly off-track a year earlier, were firmly back in the groove. Campanella led a typically unstoppable Brooklyn attack with a .318 batting average while bashing 32 home runs with 107 runs batted in—second on the team to Duke Snider’s 42 and 136. Newcombe, mimicking the team’s leapfrog start, won his first 10 starts and 18 of his first 19 before soreness in both his arm and back quieted him to a final 20-5 mark. He also showed off with the bat, hitting .359 with seven homers in 117 at-bats.

BTW: Alston was no fool and brought Newcombe to the plate as a pinch-hitter 23 times during the year.

Newcombe’s effort on the mound was the focal point of a pitching staff that finally provided the proper balance for the Dodgers, molding the team back into an all-around powerhouse. The 3.68 team ERA led the NL, and an evolving rotation was buffeted by a strong bullpen led by Clem Labine (13-5, 11 saves) and midseason rookie call-ups Don Bessent and Roger Craig.

At second and third place, respectively, the Milwaukee Braves and New York Giants simply could not match the Dodgers’ firepower. The defending champion Giants, in particular, would have plummeted even further in the standings were it not for Willie Mays’ spectacular effort (.319 batting average, 51 home runs, 127 RBIs).

Damn Yankees

For the Dodgers, the definition of “frustration” was hooking up with the Yankees in the World Series; from 1941-53, Brooklyn made five World Series appearances, all of them against the Yankees—and all of them ending in defeat. The 1955 Series would finally tell a different story.

As the Dodgers breezed, a host of American League teams were sweating it out in a taut and well-represented pennant race.

The Yankees and the Cleveland Indians were well prepared to reprise their stirring duel of the year earlier, but now they had company. The Chicago White Sox continued to emerge with a staunch, if not awesome, roster of talent; and the Boston Red Sox, energized after Ted Williams ended a brief retirement early in the season, were in the hunt as well. On August 9, all four of these teams were within a game and a half of one another.

The Red Sox, who beyond Williams and fellow outfielder Jackie Jensen provided little threat, wilted away by Labor Day. The White Sox, clinging to first place to begin September, soon caved in themselves. That cleared the field for New York and Cleveland to once again fight it out to the finish.

The Indians sensed control of their own destiny with eight games to go and a two-game cushion over the Yankees—who were suddenly without the services of a hamstrung Mickey Mantle. But the Detroit Tigers sent the Tribe reeling with a three-game sweep at Cleveland—while the Mantle-less Yankees won all eight of their remaining contests. New York reclaimed their status as kings of the AL, denying the Indians a second straight pennant by a three-game margin.

The usual suspects ignited the Yankees offense. Mantle led the AL with 37 homers while batting .309 and knocking in 99 runs; Yogi Berra had less impressive stats—a .272 average with 27 homers and 108 RBIs—but those numbers combined with his continued leadership behind the plate earned him his third AL Most Valuable Player award in five years. On the mound, manager Casey Stengel had no choice but to rejuvenate his aging pitching staff, which he did thanks to a mammoth, two-part preseason trade with the Baltimore Orioles involving 17 players—which would include two new Yankee starters in Bob Turley and Don Larsen. Turley made immediate impact, finishing at 17-13 with a 3.06 ERA to help complement Whitey Ford’s league-leading 18 wins against seven losses.

In the stretch, the Yankees were sparked by the return of Billy Martin from military service. The second baseman provided much-needed infield glue and fiery leadership, and with him the Yankees won 17 of their last 23 games.

The Indians could not catch lightning in a bottle for a second straight year despite the addition of Herb Score—anointed as the Second Coming of Bob Feller with a blistering fastball—to an already strong starting rotation. Cleveland declined mostly at the plate, as sluggers Al Rosen, Larry Doby and newly-acquired Ralph Kiner (picked up from the Chicago Cubs) all began to hit the downside of their careers.

BTW: Score produced a 16-10 record with a league-high 254 strikeouts; his 2.85 ERA was fourth in the AL.

The Brooklyn Dodgers were about as thrilled to see the New York Yankees as Adlai Stevenson was to see Ike. Losing the first two games of the 1955 World Series at Yankee Stadium only compounded the memory of losing five straight Fall Classics to the Yankees.

Falling into the hole, the Dodgers sensed that a golden opportunity to gain early control had slipped away. Don Newcombe, still ailing, was sidelined for the rest of the Series after failing to win Game One. And the Yankees’ two wins had been done without Mickey Mantle—who was coming back for Game Three. “If ever the Dodgers are going to win a World Series,” wrote the New York Times, “somebody will have to take them in hand and give them some fresh ideas.”

Powerful bats—not fresh ideas—were what the Dodgers got to wake up for Walter Alston back at Ebbets Field, a place where they had won only five of 16 previous World Series contests against the Yankees. Brooklyn took Game Three, 8-3, on a complete game performance by Johnny Podres, overcoming a Mantle home run. Duke Snider then took over. His three-run blast helped propel the Dodgers to an 8-5 Game Four victory, and he hit two solo homers in Game Five to set the pace for a 5-3 triumph. Suddenly, the Dodgers had the series lead at 3-2. But they’d been there before. And now the final two games were headed back to Yankee Stadium. The home team had won all five games thus far; the ultimate challenge was thus set for Brooklyn.

Walter Alston started Karl Spooner for Game Six, but the would-be wunderkind had no blue-chip magic left in his dead arm. He lasted all of a third of an inning, allowing all five Yankee runs in a 5-1 defeat that set up Game Seven.

Brooklyn’s Johnny Podres leaps for joy after finishing off his eight-hit shutout of the Yankees in Game Seven to give the Dodgers, finally, a world championship. (The Rucker Archive)

Without breaking stride, Amoros sprinted and reached out at the last possible moment, making the catch—and quickly firing the ball back to the infield, relayed to first base to double off a disbelieving McDougald. Yankee momentum was killed, and Brooklyn envisioned euphoria around the corner.

The Dodgers still had nine outs to earn after the Yankees’ sixth-inning threat came up empty. But Podres sailed, retiring the Yankees with ease and completing an eight-hit shutout. It could finally be said: The Brooklyn Dodgers were champions of baseball.

The borough of Brooklyn became a feel-good mob scene once the final out was made. Streets jammed. People danced. Phones were off the hook. The party went into the night. After 65 years—baseball’s relative equivalent of an eternity—the perfect moment had finally come for Dodgers fans.

It was Brooklyn’s first—and last—hurrah.

Forward to 1956: A Perfect Revenge The New York Yankees’ Don Larsen earns immortality in a day and denies the Brooklyn Dodgers their second straight title.

Forward to 1956: A Perfect Revenge The New York Yankees’ Don Larsen earns immortality in a day and denies the Brooklyn Dodgers their second straight title.

Back to 1954: At Least They Stopped the Yanks The Cleveland Indians go titanic and put a halt to the New York Yankees’ five-year American League reign—but they fall short of a world title in October.

Back to 1954: At Least They Stopped the Yanks The Cleveland Indians go titanic and put a halt to the New York Yankees’ five-year American League reign—but they fall short of a world title in October.

1955 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1955 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1955 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1955 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1950s: A Monopoly of Success Though described as a golden age for baseball, most major league teams find themselves struggling—unless you’re in New York City, where the Yankees, Dodgers and Giants hog the World Series podium from 1950-56. But as the decade winds to a close, the euphoria of Big Apple baseball will rot overnight.

The 1950s: A Monopoly of Success Though described as a golden age for baseball, most major league teams find themselves struggling—unless you’re in New York City, where the Yankees, Dodgers and Giants hog the World Series podium from 1950-56. But as the decade winds to a close, the euphoria of Big Apple baseball will rot overnight.

Jim Gentile talks about his long (and unsuccessful) road trying to crack the multi-talented Brooklyn Dodger roster in the 1950s.

Jim Gentile talks about his long (and unsuccessful) road trying to crack the multi-talented Brooklyn Dodger roster in the 1950s. Bob Roselli recalls the good life as a Milwaukee Brave, angry pitchers who didn’t hesitate to hit batters and the aura of the Yankees.

Bob Roselli recalls the good life as a Milwaukee Brave, angry pitchers who didn’t hesitate to hit batters and the aura of the Yankees.