THE YEARLY READER

1966: Wish You Were Here, Mr. DeWitt

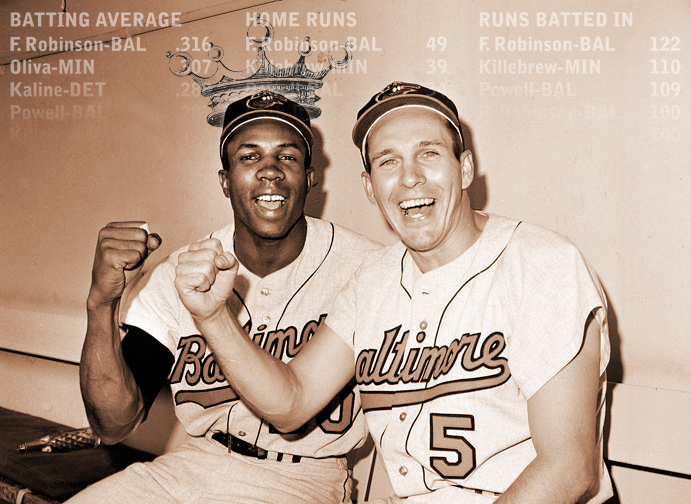

Prominent slugger Frank Robinson is ushered out of Cincinnati on account of being an “old thirty”—and makes the Reds pay for the premature prognosis by ripping apart the American League with a memorable triple crown performance in Baltimore.

Meet the Robinsons: First-year Baltimore Oriole Frank Robinson happily hangs with All-Star third baseman Brooks Robinson during the 1966 World Series. Unceremoniously shipped out of Cincinnati, Frank responded with a triple-crown effort that lifted the Orioles to their first-ever world title. (Associated Press)

“He’s an old thirty.” So spoke the mind of Cincinnati Reds owner Bill DeWitt about Frank Robinson during the spring of 1966, when a reporter asked him why he had traded his star player to the Baltimore Orioles three months earlier.

DeWitt had no problem with Robinson’s previous 10 years years as a member of the Reds. After all, Robinson had won a Rookie of the Year award, a Most Valuable Player award, a Gold Glove, and was named to the National League All-Star team six times. In justifying a trade that netted the Reds a steady starting pitcher (Milt Pappas), a closer with fading talent (Jack Baldschun) and a back-up outfielder (Dick Simpson), DeWitt ignored Robinson’s positives and accentuated the negatives—implying Robinson was a surly, prematurely aging, physically endangered superstar who spent too much time shining his shoes in the clubhouse.

BTW: This was not a racist insult; Robinson made it a custom to diligently polish his shoes.

Perhaps DeWitt was lobbying the press that he’d made the right move and crossed his fingers that Robinson would prove him correct for the Orioles. But as the 1966 season progressed, it became bluntly evident that Robinson wasn’t going to cooperate with DeWitt’s forecast.

Frank Robinson came, saw and conquered the American League, lock, stock and barrel. Only someone kneeling before him could have begged him to accomplish what he would do in 1966: Win the hitters’ triple crown, the AL MVP, the AL pennant and the World Series.

Gradually making everyone forget who they were before 1954—the hopeless St. Louis Browns—the Baltimore Orioles blossomed through the 1960s as a team strong on youthful pitching and solid defense. But outside of Jim Gentile’s flash-in-the-pan performance of 1961, the Orioles lacked an enormous power-hitting threat to raise them to an elitist level. Not Boog Powell, who showed moments of superstardom over his first few years but ultimately settled in as an inconsistent yet popular home run artist. Not Brooks Robinson, clearly a defensive icon at third base—but unqualified to solely carry the team on his back offensively.

BTW: Gentile clouted 46 home runs and 141 RBIs in 1961, but his skills depreciated and he would be out of baseball in 1967 at age 32.

For two years the Orioles had showed signs of a team desperately trying to burst into greatness. Under manager Hank Bauer, who knew something about winning after spending his playing time with the New York Yankees of the 1950s, the Orioles finished third in 1964 and 1965 with 97 and 94 wins, respectively. The missing piece to their puzzle was going to have to consist of more than fast-track growth for their youthful, talented starting rotation; the trade for Frank Robinson, many hoped, would seal the deal for Baltimore’s championship quest in 1966.

After his first month as an American Leaguer, any doubts that Robinson could promote the Orioles to powerhouse status quickly evaporated. He homered in each of his first three games to ignite the Orioles to a 12-1 start, and on May 10 at home against a Cleveland Indians team playing way over its head to begin the year, Robinson launched a 450-foot home run—the first ball to completely depart Memorial Stadium—off of Luis Tiant. At the end of that day, Robinson was hitting over .400.

BTW: After a 10-0 start, the Indians held off the Orioles through early June before slumbering to an eventual 81-81 finish.

Robinson’s bat injected a strong dose of confidence throughout the Orioles roster, and his clubhouse presence—a reported source of tension back in Cincinnati—fit more amiably with a loose team that thrived on practical jokes. But one instance of tomfoolery in August nearly cost Robinson his life. Forced into a pool by teammates at a players’ party, Robinson barely emerged to the surface with only his wildly flailing arms above water. The others gradually realized what a sinking Robinson was unable to tell them: He couldn’t swim. Catcher Andy Etchebarren dove in and grabbed Robinson out of the water, preventing a headlining tragedy.

The pool incident was probably the only challenge the Orioles were met with all summer long, as they maintained a double-digit lead almost to the end. Back on dry land, Robinson was able to complete one of the most dominating performances in AL history. He led the league in the three triple crown categories—batting average (.316), home runs (49) and runs batted in (122). He also led in runs scored (122), on-base percentage (.415), slugging percentage (.637), was second in hits (187), and third in walks (87) and doubles (34). Boog Powell (.287 with 34 homers and 109 RBIs) and Brooks Robinson (.269, 23 and 100) comfortably eased into newfound supporting roles in the lineup. A no-brainer choice for the MVP, Robinson became the first—and still, only—player to win the award in both leagues, having won the NL honor in 1961.

The defending AL champion Minnesota Twins caught fire after the All-Star break, but it wasn’t enough to make up for a sub-.500 start that handicapped their chances. The Twins wrapped the year up nine games back in second place.

The defending world champs, the Los Angeles Dodgers, almost began their quest for a repeat performance without the two guys who got them there the year before: Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale.

The two star pitchers, who each made $80,000 in 1965, were jointly determined to a get a raise—a big one—for 1966. That wasn’t all. Within their demands they broached two of baseball’s biggest pre-free agency taboos: Asking for a multi-year contract—$500,000 per player over three years—and using an agent to negotiate that contract. Koufax, Drysdale and agent Bill Hayes very publicly went before the media and warned that if Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley and general manager Buzzie Bavasi didn’t give them what they wanted, they would walk away from the game and start acting careers in nearby Hollywood.

As negotiations stalled, Koufax and Drysdale reminded the Dodgers that they’d call on other teams inquiring of their interest. The Dodgers in turn reminded the two about the reserve clause and its meaning. Bill Hayes responded by saying he had enough legal precedent to successfully challenge the reserve clause. The Dodgers, unwilling to consider Hayes’ threat a bluff—and also aware that the players’ union was about to hire a bona fide labor star in Marvin Miller—flinched. But not before they got Koufax and Drysdale to settle on just one year for, respectively, $125,000 and $110,000.

While Drysdale stumbled through 1966 with a 13-16 mark (in spite of a decent 3.42 earned run average), Koufax reaffirmed the belief that no matter how much money he earned, it wasn’t enough. For the fourth straight year, the Dodgers southpaw was simply impeccable. He topped his previous career bests with 27 wins (against nine losses) and a 1.73 ERA, while striking out 317 batters.

Koufax’s superhuman achievement masked a tortuous pain. Arthritis had developed in his pitching arm, and everything under the sun—if not under the table—had been given to Koufax to ease the hurt. Cortisone shots, codeine, butazoldin—even a dangerously toxic concoction called Capsolin, made from chili peppers—were all used during the season to keep Koufax as game-ready as possible.

BTW: A sweatshirt worn by Koufax with residue of Capsolin was put on by teammate Lou Johnson—who soon suffered from skin blisters and vomiting.

Scratching Out the Pennants

The Dodgers may have won three National League pennants during the 1960s, but offense had very little to do with it. As the NL rankings, the success of the Dodgers during this decade came down to one word: Pitching.

Koufax’s 41st and final start of the regular season’s last day was the season’s most crucial. It was determined that a Dodgers loss would have opened the door for the possibility of a tie-breaking playoff against the San Francisco Giants. Aware of how luckless their postseason history with the Giants had been over the years, the Dodgers took no chances and placed Koufax on the mound with only two days’ rest. No matter, he led the Dodgers to a 6-3 win over Philadelphia and a clinching of Los Angeles’ third NL pennant in four years.

BTW: How was Cincinnati, minus Frank Robinson? The Reds finished seventh at 76-84—their first losing season since 1960.

The script for the Dodgers’ success had rerun written all over it: Outstanding pitching bailing out an impotent offense once more near the bottom of almost every major NL hitting category. Beyond Koufax and Drysdale, the rest of the starting rotation began to develop with Claude Osteen (17-14, 2.85 ERA) and rookie Don Sutton, who despite a middling 12-12 mark still made heads turn with a 2.99 ERA and 209 strikeouts. In the bullpen, closer Phil Regan won 14 and saved a league-high 21 games—losing just once—with a 1.62 ERA.

Frank Robinson returned to the plate against National League pitching in grand style when he homered in his first World Series at-bat against Don Drysdale—a pitcher who had given him nothing but fits while playing for the Reds. The solo shot capped a three-run outburst in the first inning for the Orioles off Drysdale in Game One—but the lead was in jeopardy a few innings later as Baltimore starter Dave McNally was getting shakier by the batter. After walking the bases loaded in the third, McNally was removed for reliever Moe Drabowsky, who would be no stooge on the mound. Over the next six-plus innings, Drabowsky would shut down the Dodgers on a hit and two walks—while striking out 11, six in a row at one point—to preserve a 5-2 win.

The Dodgers, who scored twice in the first three innings of Game One, would not cross home plate again in the Series.

Koufax, starting Game Two because he needed the rest after winning the regular season finale, was victimized by his own team’s defense—especially that of outfielder Willie Davis, who endured a horrific fifth inning when he committed three errors and crossed up with fellow outfielder Ron Fairly on another routine fly ball by Robinson that fell between them for a triple. Overall, the Dodgers made six errors that led to three unearned runs, and scored no runs of any kind thanks to 20-year-old Orioles starter Jim Palmer—who proved his pre-game claim that the Dodgers couldn’t hit a high fastball by tossing a four-hit, 6-0 shutout.

BTW: The six Dodger errors in Game Two were the only ones committed by either team in the entire Series.

Sandy Koufax desperately tries to get the Dodgers back on track in the World Series against the Orioles—but he would get no support from his teammates either at the plate or on the field. It would be the last time he’d ever pitch. (Associated Press)

Returning to Baltimore brimming with confidence after winning the first two games at Los Angeles, the Orioles would only need two solo home runs over the next two games to complete the Series sweep. In Game Three, Paul Blair zapped a fifth-inning homer, and Wally Bunker made it stand up by blanking the Dodgers on six hits. A day later, a far less erratic McNally returned to the mound and shut the Dodgers down on four hits. Offensively, the difference was Robinson, whose solo home run in the fourth helped secure Baltimore’s first-ever World Series triumph.

BTW: The Dodgers set all-time World Series lows with two runs and a .142 batting average against the Orioles, making only their second World Series appearance; the first took place in 1944 when the franchise was known as the St. Louis Browns.

In a season-long triumph, Frank Robinson played anything but an “old thirty.” So had Sandy Koufax. But Koufax felt like one.

A month after the World Series, the 30-year-old Koufax decided that he couldn’t take the agony anymore. Admitting he had pitched pain-free only once during the entire 1966 season, Koufax told a media-packed room that he was retiring, warned by doctors that his arm risked permanent damage if he continued to pitch.

There has been, and always will be, great debate over whether Sandy Koufax is the greatest pitcher of all time. What is far less debatable is whether, in a four-year period from 1963-66 in which Koufax won 97 games, lost 27, tossed 31 shutouts, struck out 1,228 batters and put together a 1.90 ERA, anyone else has thrown as magnificently over a similar stretch.

Forward to 1967: The Impossible Dream The Boston Red Sox get serious after a decade of living a mediocre, country club-like existence.

Forward to 1967: The Impossible Dream The Boston Red Sox get serious after a decade of living a mediocre, country club-like existence.

Back to 1965: The Fall of the Yankee Empire After decades at the top, the New York Yankees are brought down by a combination of old age, nagging injuries and arrogance.

Back to 1965: The Fall of the Yankee Empire After decades at the top, the New York Yankees are brought down by a combination of old age, nagging injuries and arrogance.

1966 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1966 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1966 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1966 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1960s: Welcome to My Strike Zone In a decade where baseball as a tradition is turning stale with America’s emerging counter-culturism, major league owners see its biggest problem to be, of all things, an overabundance of offense in the game. The result? An increased strike zone, further contributing to a downward spiral in attendance, but greatly aiding an already talented batch of pitchers.

The 1960s: Welcome to My Strike Zone In a decade where baseball as a tradition is turning stale with America’s emerging counter-culturism, major league owners see its biggest problem to be, of all things, an overabundance of offense in the game. The result? An increased strike zone, further contributing to a downward spiral in attendance, but greatly aiding an already talented batch of pitchers.

Ernie Fazio admits what most others couldn’t imagine: That he loved playing and working for mercurial A’s owner Charles Finley.

Ernie Fazio admits what most others couldn’t imagine: That he loved playing and working for mercurial A’s owner Charles Finley.