THE BALLPARKS

Target Field

Minneapolis, Minnesota

(iStock)

With Target Field, the Minnesota Twins dared to return to the outdoors, bookending beautiful summer dates with early- and late-season fates mixing cold, wind and possibly snow. But it’s all worth it at a ballpark that’s hard not to love, an inviting and modern ode to land and city that welcomes its fans with open arms and entertains them with courteous charm.

Summer is coming. That’s the refrain that echoes through the long winter across Minnesota, where 10,000 lakes are frozen, green is nonexistent, and water vapor from tailpipes and human mouths seem to hang forever in the air. The people here long for the warmth of spring and the summer to follow, eagerly awaiting Opening Day like “recovery from a serious illness,” as Minnesota native Garrison Keillor once wrote.

When that Opening Day does come around, fans of the Minnesota Twins shed a layer or two of wintertime clothing and once more embrace Target Field, the team’s fabulous home since 2010. The downtown ballpark, mixing limestone, angling glass and steely curves, is not merely the home of the Twins but a beacon of hope that Minneapolis, sitting exactly between the North Pole and Equator on the 45th parallel, will win an early springtime tilt toward warmth.

Making the pilgrimage to Target Field is blissfully easy. Two freeways, one which partially, literally tunnels under the ballpark, deliver vehicles whose occupants can choose from an abundance of nearby parking garages. Two light rail lines, ferrying passengers from St. Paul and Bloomington, stop just steps from Gate 6, numbered as such to honor former Twins Hall of Famer Tony Oliva. Rolling in perpendicular is the Northstar rail service, reaching out toward the northwest suburbs. There’s a bus transit station a block away. If you even feeling like grinding it to Target Field on a bicycle, there’s a paved trail running parallel to the rail tracks under the ballpark’s third-base end, and hundreds of racks to securely lock it against.

It’s hard to believe that a ballpark so beloved experienced years of stubborn opposition in getting built, as few if any other major league venues had to run as long and painful an obstacle course before becoming reality. But this is Minnesota, where fiscal accountability is paramount to John and Jane Q. Public, and the phrase “spare no expense” is a dirty phrase. One wonders if it’s called the Bread and Butter State for something other than flour and dairy.

But for those who’ve lived the Target Field experience, it seems incredulous that the facility doesn’t get mentioned more prominently when the subject of great ballparks is brought up. The venue tends to play the sleeper role in such conversation that typically defaults to the usual suspects of Fenway Park, Wrigley Field, and more recent notables as Oracle Park and PNC Park. But whenever an online media outlet decides to name its ranking of major league ballparks, Target Field almost always ends up somewhere into the top five. ESPN the Magazine went so far in 2010 to declare Target Field as the #1 sports stadium experience in North America. “Target Field,” wrote the Minneapolis Star Tribune’s Jim Souhan, “became to downtown Minneapolis what the North Star is to the night sky.”

From Met to Metrodome to “Meh.”

Resettling from Washington, D.C. into erector-set Metropolitan Stadium in 1961, the Twins experienced two decades’ worth of the region’s brutal Arctic air that sometimes hung around well after Opening Day—and sometimes returned before Fan Appreciation Day. Moving indoors to the Metrodome, closer to downtown, rid the Twins of such meteorological issues, but different ones propped up as the new venue became an immediate eyesore, with turf too bouncy, a fabric ceiling too low, and sightlines too undesirable. Winning world titles in 1987 and 1991 in front of packed, eardrum-busting crowds would provide happy, nostalgic memories—but the Metrodome, despite actually making money for the taxpayers who okayed it, was otherwise a joint that the Twins couldn’t wait to flee from.

The Twins said the loud part even louder in 1994 when owner Carl Pohlad, who rescued the franchise from departure just a few short, miserable years into its Metrodome tenure, publicly stated his desire to move into a new ballpark. Pohlad’s statement couldn’t have been timed any worse; here was the second richest guy in Minnesota asking the state’s famously fiscal-minded citizens to build him a palace, just weeks before the game of baseball shut down from a devastating labor war waged between wealthy owners and players.

The 1994-95 work stoppage left a bitter aftertaste; Pohlad was never going to win over non-fans with a request for a new ballpark, but he had just as hard a time convincing die-hard Twins fans to get on board. Sure enough, poll after poll taken of potential voters showed overwhelming dissent on any new ballpark measure—regardless of how much it cost, how it would be built, or where it would be located.

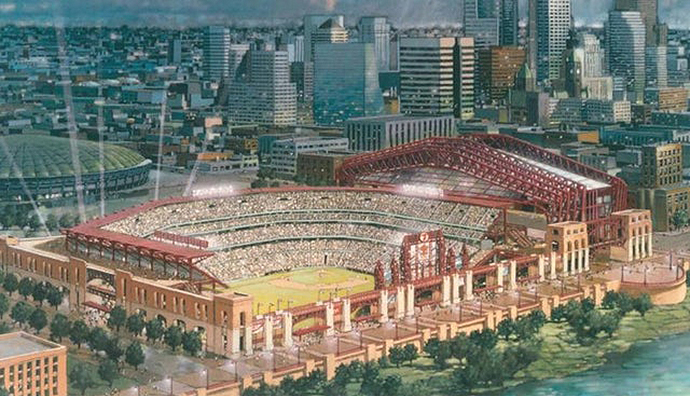

Before the Warehouse District location where Target Field now sits was selected, the most alluring site for a Minneapolis ballpark was along the banks of the Mississippi just a few blocks north of the Metrodome (left), where a retro-designed facility with retractable roof was imagined.

Arlington This is Not.

For the next decade, the Twins, along with the city, county and state, tried to nail down a new ballpark. Again and again and again. They were buffeted with more citizens groups, ballpark committees and task forces than you could count. Minnesota Wins. Twinsville. Citizens United for Baseball. C-17. And on and on.

All sorts of funding schemes were introduced. One had Pohlad giving 49% of team shares to the public while donating $82 million to a $354 million ballpark budget. (The scheme faded when it was revealed that Pohlad’s contribution would actually be a loan.) Another idea had a ballpark paid for by casino revenue, which upset Native American gaming interests which ran the slots and tables. Yet one more thought had a new venue paid for by cigarette taxes, which upset, well…smokers. Those avenues exhausted, Pohlad suggested donating the team to a non-profit group, but only if that group—again, a non-profit—could pay off his $86 million debt on the Twins.

Though Minneapolis was the assumed location for any new ballpark, other cities got in on the act. Neighboring St. Paul was given two opportunities; one was denied by 58% of its voting public, the other died when it became clear that the city had neither the financial nor infrastructural clout to make it happen. Much farther away, a ballpark vote in, of all places, Greensboro, North Carolina would determine the Twins’ future. If the people there said yes, Pohlad would agree to sell the team and have it moved east. But the Carolinians said no by a resounding 2-1 margin—leaving Pohlad to wonder if anyone even wanted the Twins around anymore.

Bud Selig began to wonder, too. Baseball’s commissioner was losing patience with the situation. Throughout the 1990s, he had made a habit of traveling to one major league city after another lobbying for new ballparks, layering the request with the threat of the team leaving if one wasn’t built. Selig performed the same song-and-dance-and-blackmail routine to Minnesota politicians, but they yawned. It was obvious that a new Twins ballpark would be, by far, his biggest challenge. So he shuffled into his pocket and pulled out the nuclear option; no new ballpark would mean no Twins, period.

Selig’s 2001 effort to eliminate the Twins, along with the neglected Montreal Expos, from Major League Baseball only added to the anger of Minnesota baseball fans who felt they were screwed enough by the game’s growing fiscal disparities that made the Twins a no-name, small-market ballclub with, at one point, an aggregate payroll less than one player (Texas’ Alex Rodriguez). But they found a savior: Hennepin County Judge and sports fan Harry Crump, who ruled against the Twins’ contraction because the team needed to honor its ongoing lease at the Metrodome. A legal rep for both the Twins and MLB grouched at Crump’s ruling as “Homer Hankie Jurisprudence.”

Denied the electric chair, the Twins lived on but still needed a new ballpark. In 2000, they avoided the embarrassment of drawing under a million fans by a mere 761. Other teams were performing in or building revenue-consuming ballparks. The Twins were simply falling farther and farther behind. The Pohlad regime felt “hopelessness” at the situation.

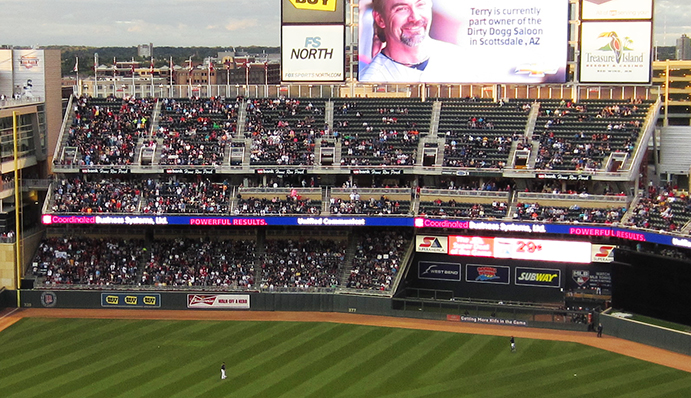

Fans seated along the left-field line at Target Field get the best view of downtown Minneapolis. (Wikimedia—Schwerdf)

Have I Got a Parking Lot For You.

One day in 1999, as one ballpark proposal after another was being shot down, Bruce Lambrecht stepped out onto Rapid Park, an eight-acre surface parking lot he owned west of downtown Minneapolis. He had ‘ballpark’ on his mind, and here’s why: From his vantage point, he got an eyeful of downtown and a glut of transit options—parking garages, freeways, rail—that were steps away. Plus, the lot was adjacent to the Hennepin Energy Recovery Center (HERC), which converts garbage to steam and energy; perhaps there could be an environmental angle to a ballpark by taking advantage of HERC’s capabilities.

Lambrecht’s parking lot had barely received a sniff while multiple other locations were being boosted as a possible landing spot for a new Twins ballpark. The dreamiest of the options was a space a few blocks north of the Metrodome along the banks of the Mississippi with a retractable roof. Sure, Lambrecht thought, a riverfront yard had a romantic feel to it, but his thinking was more in tune with the average Minnesota voter who valued functionality over glamour. His site had plenty of the former; anything of the latter would be a bonus.

With an evolving team of local architects, engineers, shakers and movers, Lambrecht’s vision for a Twins ballpark in what was known as the Warehouse District grew legs and eventually grabbed the attention of Hennepin County commissioners who, by 2005, decided to give the troubled new ballpark saga another shot. Huddling with the Twins, the county forged a new scheme—with the team paying one-third of the cost for the new venue at Lambrecht’s parking lot, while the county paid the rest via a 0.15% sales tax increase. But what would county voters think? The question was moot; thanks to a 1997 state law, any county could pass a tax increase without a referendum, so long as the Governor approved it.

Enter Tim Pawlenty. As a member of the state legislature during the 1990s, the fiscally conservative Republican frowned on repeated attempts at a new ballpark, publicly rattling off the usual talking points of not willing to subsidize billionaire owners and millionaire players. But now he was Minnesota’s Governor, a traditionally more dignified and tempered position. He no longer saw a new ballpark as an evil public works project to benefit private fat cats, but as something that, hey, maybe it should be built—because he didn’t want to be known as the guy who let the Twins and pro football Vikings (also clamoring to leave the Metrodome) leave the state on his watch.

Late in 2005, Pawlenty somehow managed to get the state’s key legislative leaders on board with Hennepin County’s ballpark package at Bruce Lambrecht’s parking lot. Next came the hard part: Getting the majority of everyone else to approve during the Spring 2006 legislative session in St. Paul, as a ballpark measure made the docket for what seemed the umpteenth time. Pro-ballpark voices had to sweat out an attempt by House members insisting that they would vote for the measure only if the county public got a say via a referendum; that idea was rejected, but by a mere two votes. Carrying on, the House approved the ballpark by a 71-61 margin—followed by an even slimmer 34-32 edge in the Senate. The Twins, finally, had their ballpark.

Governor Pawlenty, the former anti-ballpark rebel, donned a Twins jersey and officially signed the bill approving Target Field in a pregame ceremony before a May 26, 2006 game at the Metrodome, draped by Carl Pohlad and Minnesota baseball legends Harmon Killebrew and Kent Hrbek.

The exterior of Target Field in the evening. Part of Interstate 394 can be seen at right, heading under the right-field entry plaza; the other part is fully underneath the ballpark and plaza. Elevating the ballpark above the freeway, and railroad tracks on the other side, was the only way to squeeze the facility into a remarkably tight space. (Flickr—MacH)

Squeeze Play.

When awarded the job to draw up Target Field, Kansas City-based sports architect Populous and its lead designer Earl Santee thought they’d been handed the Kobayashi Maru of ballpark design: A seemingly insurmountable task, a no-win scenario. The first and foremost concern was space; at eight acres, Target Field had even less real estate to play with than Chicago’s cramped Wrigley Field, which weighed in at a relatively spacious 10 acres. Providing further stress was the surroundings, as the site was tightly hemmed in by railroads, a freeway and parking garages, while an underground creek below would make construction stability difficult. It all amounted to what Populous later described as “a complex labyrinth…one of the most challenging projects in (our) history.”

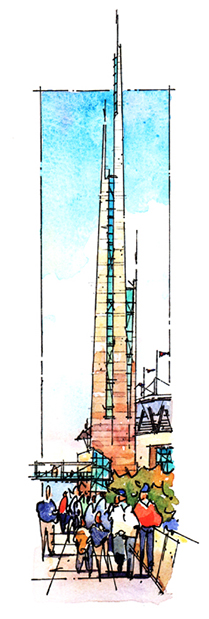

Among the ideas that failed to make the final cut for Target Field was a 300-foot-tall icicle-like structure that attached itself to the foul pole.

Showing that it wouldn’t monopolize the ballpark design process, Populous set up shop in its Manhattan offices in September 2006 and invited all relevant stakeholders—the Twins, the ballpark authority and partnering designers—to a weekend think tank confab to whip up ideas on Target Field’s look. Many of those dreamt up would make the final cut; others, such as 300-foot-tall icicle-like structures attached to the foul poles, and waterfalls behind center field, would not.

The brainstorm sessions resulted in a ballpark that would be dressed in an unusual but wondrous mix of stone, glass and slick steel—a “modern interpretation of the state’s natural creations,” as told by Target Field’s ballpark authority.

The bulk of Target Field’s exterior is composed of Kasota limestone, quarried out 75 miles southwest of Minneapolis. Cool-tinted glass provides an unusual but pleasing contrast. (Bigstock)

Stone Gold Lock.

Target Field’s exterior mostly consists of 2,400 tons’ worth of Kasota limestone, a warm brand of native stone carved out of the Vetter Stone Company 75 miles southwest of Minneapolis; it’s the same limestone used to adorn Pittsburgh’s PNC Park. Showing that Target Field isn’t some sort of impenetrable fortress, the stone is strategically interrupted with varying displays of cool-tinted glass. The glass especially dominates in several extensions from the main structure, near the home plate and right-field corner gates, slinging out at mod angles and looking something like a superyacht trying to break free from an Egyptian pyramid. Topping it all is a smooth, boomerang-shaped roof that covers much of the upper deck and sharpens off to a knife-edged end. Its sleek appearance is a departure from the exposed steel seen at retro ballparks—and makes it tough for birds to camp out and take a dump on fans below.

“It’s got a lean to it,” said Bill Blanski, one of the local architects who partnered on Target Field’s design, to author Steve Berg. “Its geometry and form appear to be in motion. It reaches out to grab the space of the city, but the neighborhood is also invited back in.”

While Target Field’s façade was taking shape, the county had a harder time trying to secure the ballpark property it needed. Burlington Northern Santa Fe, which owned the railroad tracks at the west end of the site, initially balked at the county’s request to have the rails moved outward, a dissidence that could have threatened the whole project. (An agreement was eventually reached.) A bigger headache emerged with the purchase of Bruce Lambrecht’s parking lot, now under a cooperative named Land Partners II. Originally, the county had agreed to a two-year window in which it could buy the property for $12 million, but that window expired before the state approved the ballpark. Eyes widened with illusions of enhanced valuation, Land Partners II now asked for a whopping $65 million. The county, anticipating a far lower purchase to meet its budget, aggressively counter-punched by declaring eminent domain over the land so they could seize it. Legal proceedings ensued, and by 2008 a court settlement basically split the difference at $29 million; the Twins pitched in to offset the monetary loss to the county.

A Nightlife All of Its Own.

For all of the Twins’ perceived penny-pinching during the ballpark approval process, the team did go beyond the budget and threw an additional $55 million into the pot to spice up the joint; after years at the austere Metrodome, the team didn’t want to move from one no-frills environment to another. There were the little things, such as placing handles the shape of the state of Minnesota on the exterior gates. A bit more visible was the installation of 10,000 beige wooden seats—a rarity in the age of plastic—to harmonize with the cream-colored limestone, and a gimmicky extension of the right-field bleachers over the warning track by as much as 8.5 feet, perhaps as a nod to Detroit’s old Tiger Stadium. But for true retro appeal, Target Field’s most notable eye candy is a rooftop-style sign above the center-field bleachers, a remix of the classic Minnie & Paul logo from the Twins’ early days showing two ballplayers on opposite sides of a bridge over the Mississippi shaking hands. Through neon lights, the hand-shaking goes into motion whenever a Twins player hits a home run; the sign operator was apparently asleep at the wheel and the display stayed darked when Jason Kubel became the first such player to go deep at Target Field.

Here, there and everywhere within Target Field are fashionable options to wine, whine, dine and opine. It seems you can’t walk more than 30 feet in the various concourses without stumbling upon a bar, lounge or dining establishment; the collection is so omnipresent, it could conceivably create a nightlife all of its own even if the Twins weren’t in town.

The menu of choices is apparent from the moment fans walk up to the ballpark’s southeast corner at Gate #34—numbered in honor of perennial Twins batting champ Kirby Puckett. Sticking out of Target Field’s middle decks and overlooking the area is the brewpub-style restaurant Truly on Deck, which formerly went by the names of (originally) the Metropolitan Club and later Bat & Barrell. Below, on the grounds of Schneiderman’s Lawn—a grassy picnic magnet with lawn chairs and cornhole set-ups—is Jack Daniel’s Bar (no further explanation needed). Behind home plate is Hrbek’s Pub, a shrine to former star Twins first baseman Kent Hrbek which one web site referred to as “a body swamp of Bloody Mary fans” and shows off various Twins logos plastered both on the floor and ceiling. Above on the third deck is Twins Pub, which doubles as the home of Target Field organist Sue Nelson because, as she says, “I can play and talk.”

Elbowing in at the left-field corner between the primary ballpark structure and the three-tier bleachers is a multi-level assemblage of more perishables. There’s the Gray Duck Deck, the Summit Brewing Pub and the Town Ball Tavern, an ode to former local ballclubs and, somewhat irrelevantly, features the same flooring used by basketball’s Minneapolis Lakers before their move to Los Angeles. Topping this area is the open-air Budweiser Roof Deck, which includes a large fire pit, the ballpark’s best views of downtown Minneapolis and, of course, beer; but it’s reserved much of the time for prepaid groups, so spur-of-the-moment access is not always a given.

Finally, for the bleacher bums, there’s Minnie & Paul’s—placed unsurprisingly below the big Minnie & Paul sign in center field—featuring pizza, burgers and a full bar with good sightlines of the game in action, even if it is over 400 feet away.

Target Field’s most nostalgic touch is the neon-lit Minnie & Paul sign, combining the Twins’ first logo with their more current identity above. The shaking hands go into motion whenever a Twins player hits a home run. (Flickr—Steve)

How Green Was My Ballpark.

To say that Target Field has mirrored the state’s reputation for aggressive recycling and progressive environmental policies is an understatement, as the ballpark has gone above and beyond to conserve and reuse whenever possible. In its first decade, Target Field diverted over 13,000 tons of waste from landfills and captured 20 million gallons of rainwater to be purified and reused to rinse off the seats, water the field, or be redirected to the venue’s clubhouses, suites and offices to deter use of bottled water. On the food front, Target Field is often ranked near the top of the list for vegan-friendly ballparks, per PETA (People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals). And rather than just trash leftover ballpark food at the end of the night, the Twins truck it over to local charities to feed the homeless and other folks in need.

Although the adjacent Hennepin Energy Recovery Center (HERC) is a sore point for a few who tag it as one of Minneapolis’ worst polluters, its ability to convert garbage to steam and energy has been a boon for the Twins, who use the facility to heat the water at Target Field.

All of the above has led Target Field to earn some highly prestigious environmental honors. When built, it was given LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) Silver certification from the U.S. Green Building Council, making it the second MLB ballpark after Washington’s Nationals Park to be granted that status. In 2019, Target Field was certified LEED Gold for Operations and Maintenance, making it the first pro sports franchise anywhere in the world to be given such a designation.

Win the Beginning.

The weather gods cooperated and then some on Opening Day 2010, as Target Field opened for the first time on a beautifully sunny 65-degree afternoon. The hard part of building the ballpark, with its difficult choreography of a tight footprint and mass storage of construction materials, was finally in the rear-view mirror. The Twins expressed their appreciation for that effort by bringing out Dave Mansell, the prime mover for Target Field builder Mortensen Construction, as one of three people to throw out the ceremonial first pitch. (Hennepin County Commissioner Mike Pat and Twins President Jerry Bell, both of whom were crucial in making the ballpark a reality, were the other two.) The scene was worthy of an All-American, Fourth of July experience with decorative bunting, a large American flag unfurled on the field, fireworks and a flyover of fighter jets.

Against the Boston Red Sox, the Twins couldn’t have been handed a better script. They scored twice in the first inning and once in the second, building a quick lead they would not relinquish as Carl Pavano sailed for six strong innings; the bullpen covered it the rest of the way. The 5-2 victory delighted the sellout crowd of 38,145, roughly two-thirds of which represented a club-record number of season ticket holders.

The feel-good vibe carried through the rest of the 2010 season. Target Field sold out all but twice, never drawing a crowd under 38,000; the 3,223,640 fans passing through the gates set a franchise mark. The only reason five other MLB teams drew more that season was because their ballparks had higher capacities. On the field, the Twins responded to the enthusiasm by fielding an AL-best 53-28 record at home, including a 26-10 mark against AL Central competition—a key factor in securing their sixth divisional title in nine years, all coming after the contraction flap. Visions of a first-year world title at Target Field quickly diminished in the first round of the playoffs when the New York Yankees, who would develop into the Twins’ postseason Kryptonite, overcame early Minnesota leads in two games at the new yard and eventually finished off a three-game sweep. Financially, the 2010 season was a profitable boon for both the Twins and the local economy, which collected $18.6 million in sales and tax revenue—three times that of the team’s final season at the Metrodome.

Sixteen days before the Twins’ inaugural contest at Target Field, the University of Minnesota and Louisiana Tech played the ballpark’s first game before a crowd of over 20,000. The Golden Gophers’ T.J. Oakes delivers the first pitch to Kyle Roliard. (Wikimedia—Jon Marthaler)

Mighty With the Ivy.

The only gripes about the ballpark came from Twins hitters, whose power seemed to be sapped by its field dimensions—never mind that they were nearly identical to those of the hitter-friendly Metrodome.

Only three MLB ballparks yielded more home runs in 2010. Popular catcher Joe Mauer, after belting 28 homers during the Twins’ last year at the Metrodome, hit just one at Target Field among a total of nine. Slugging teammate Justin Morneau, owner of 30 homers a year earlier, managed only four of 18 total at the new ballyard. “Right-center to left-center is ridiculous,” Morneau said then.

Overall, hitters blamed Target Field’s less idyllic background for the drop-off. Part of the issue was glare from the Minnie & Paul sign above the center-field bleachers, but the bigger problem was the batters’ eye below. A collection of 14 spruce trees, planted behind the outfield wall, were as dark as the surrounding scene—but they created contrasting shadows and brightness from the sun; it only got worse when they began to sway in the wind. The batters’ eye itself was brushed with semi-gloss paint, making it too reflective. While the trees were removed after 2010—keeping true to their pro-green dogma, the Twins didn’t “chop” them down but had them replanted elsewhere—the batters’ eye proved a far more stubborn issue than anticipated. It was first repainted in a less glossy dark green, then black, then plastered over with, as Fox Sports described it, “aluminum honeycomb-style materials used to make aircraft bodies that need to be re-angled so the top didn’t glow as much.” But none of these solutions appeased the hitters. Finally in 2019, juniper plants were draped over the batter’s eye, resulting in an ivy-like appearance akin to Chicago’s Wrigley Field.

The vines became divine for the hitters. During the ivy’s first season at Target Field, in 2019, the Twins demolished major league records both for home runs at home (170) and for the entire season (307). Five different Twins hit at least 30, another all-time mark.

Target Field’s left-field bleachers consist of three levels to mimic those at Metropolitan Stadium, the Twins’ first home from 1961-81. (Flickr-Steve)

Don’t Blame the Ballpark.

Strangely, in the afterglow of a terrific debut all the way around at Target Field, the Twins dimmed into an era of depression on the field. The team crashed to 99 losses in 2011, then lost at least 90 in four of the next five seasons. It was a shocking sequence for a franchise that begged for a new ballpark to stay competitive and, once they got it, couldn’t do so. As a result, erosion of the new ballpark’s honeymoon phase accelerated, with attendance dropping from the three-million range to below two million by 2016, when the Twins’ hit the nadir with a Minnesota-record 103 losses. Even when they rebounded, spectacularly, to 101 wins in 2019, Target Field did not see a major resurgence at the gate; the majors’ fourth-best team (by the record), with all those home runs, resulted in a gate of 2.2 million—a respectable figure, but only good for 15th out of 30 teams in MLB. The 2020-21 COVID-19 pandemic, and a new era of hostile owner-player labor relations that followed, has further squashed a mass return of Minnesota fans back to the ballpark.

Target Field is not to blame. If anything, its presence has kept those who continue to show up highly satisfied, regardless of the result on the field. As a testament to its early endurance, little improvement has been made to the ballpark, in large part because none has been needed. Early on, a modest version of the ballpark’s main scoreboard was placed over the right-field seats for those with an inconvenient view (if any) of the big board. There’s otherwise been the usual enhancements to stay in sync with ballpark trends, such as lounge-like concessions, contactless payments and a sensory suite for neurotypical spectators. But Target Field remains as it always has been and will likely stay that way, with no structural changes and a field that retains the same dimensions as it did back in 2010.

Swiping a page from Detroit’s extinct Tiger Stadium, a segment of Target Field’s right-field bleachers sticks out over the warning track, which in theory could steal a towering deep fly out from an outfielder. (Flickr-Gutenfrog)

Pick Your Target.

As expected, Target Field is immensely easy to get to. At the left-field corner of the venue, Target Field Station was built to coexist with the ballpark, bringing in fans from rail and light rail into an area that includes an amphitheater holding up to 1,000 people for pregame concerts and other gatherings who might come for viewings of sports events or movies shown on a 16×29-foot video board.

But it’s the expansive Target Plaza, on the other side of the ballpark behind the right-field corner, that’s the primary meeting place for Twins fans arriving via car or bus—and contains a good deal of Twins kitsch to enjoy before strolling up to the entry gate. A giant gold glove sculpture that fans can sit in and pose for photos is dedicated to Twins Gold Glovers of the past, and is located 520 feet from home plate—the same distance as the longest home run hit in Twins history, by Harmon Killebrew. (Irony: Killebrew never won a Gold Glove.) The nearby flag pole is the same one used at Metropolitan Stadium, where Killebrew smashed his titanic blast in 1967. There’s nine 40-foot-tall, bat-shaped topiary plants lined up in a row that light up at night—one lit after the first inning, two after the second, and so on. Finally, to mask the potential eyesore of a parking garage overlooking the plaza, a 285×60-foot piece of art entitled the Wave Wind Veil is draped over the garage’s façade, containing 51,000 pieces of aluminum that flap in the wind; when the wind hits it, it looks like the projection of a time lapse satellite video of cloud movement. At night, multi-colored LED lights make the veil come alive to more prismatic life.

Four of the ballpark’s six statues are located at Target Plaza, honoring Killebrew, Rod Carew, Kirby Puckett and former Twins owner Carl Pohlad (who died a year before Target Field’s completion) with his wife Eloise. There was a seventh statue: Calvin Griffith, the owner who brought the team from Washington to Minnesota in 1961. In 2020, Griffith’s bronze likeness was taken down in the aftermath of the George Floyd riots and Black Lives Matter protests when people recalled his 1978 racist rant at a Lions Club function—the one that expedited the departure of Carew, who famously insisted that he wouldn’t be “another nigger on (Griffith’s) plantation.”

The once maligned Warehouse District has become chic with Target Field as its anchor. While the area immediately west of the ballpark remains dominated by warehousing, the area to the north—wedged in between the ballpark and the Mississippi—has thrived with nouveau development, as historic buildings have been transformed into alluring business centers, residences and micro-breweries; you know your area is hip when Amazon brings office space to the scene.

Target Field contains a most interesting provision. Should anyone attempt to, once again, ‘eliminate’ or move the Twins before 2040, the State of Minnesota would retain the rights to the Twins brand and history—its name, logos, colors and records. This is how serious the loyalty to the Twins and to the game of baseball has become in Minnesota. Target Field had responded in kind; through snow, sleet or summer thunderstorms, through the thick and thin of the Twins’ performance, the beautiful ballpark will always be there—with all of its charm, its multitude of fine and fun dining/lounging experiences, and the pleasure of enjoying this great game the way it was meant to—outdoors on real grass.

It’s almost as if Minnie & Paul are looking down upon the scene from their stand above center field, shaking hands to a job well done.

The Ballparks: The Metrodome Ugly, cheap and purely artificial, the Metrodome reigned as the Yugo of ballparks, a synthetic spit at yesteryear with fake grass, fake wind and a bed sheet for a roof. While it kept out the rain, snow and red ink, it couldn’t prevent a flood of insults from just about everyone who entered through its wind-blasted revolving doors. Yet no team enjoyed a better home advantage than the Twins, who excelled within the venue’s occasional ear-shattering din.

The Ballparks: The Metrodome Ugly, cheap and purely artificial, the Metrodome reigned as the Yugo of ballparks, a synthetic spit at yesteryear with fake grass, fake wind and a bed sheet for a roof. While it kept out the rain, snow and red ink, it couldn’t prevent a flood of insults from just about everyone who entered through its wind-blasted revolving doors. Yet no team enjoyed a better home advantage than the Twins, who excelled within the venue’s occasional ear-shattering din.

The Ballparks: Griffith Stadium Your ballpark has burnt to the ground and you’ve got three weeks before Opening Day. Quick—whaddyado? Ask the Washington Senators, who performed the ultimate rush job and constructed Griffith Stadium as one of the more architecturally coarse and confusing of venues, with a playing field so distant and awry, the whole outfield became Triples’ Alley. Fans and presidents were nonetheless thrilled by the breathless action between the lines.

The Ballparks: Griffith Stadium Your ballpark has burnt to the ground and you’ve got three weeks before Opening Day. Quick—whaddyado? Ask the Washington Senators, who performed the ultimate rush job and constructed Griffith Stadium as one of the more architecturally coarse and confusing of venues, with a playing field so distant and awry, the whole outfield became Triples’ Alley. Fans and presidents were nonetheless thrilled by the breathless action between the lines.

Minnesota Twins Team History A decade-by-decade history of the Twins, the ballparks they’ve played in, and the four people who are on the franchise’s Mount Rushmore.