THE YEARLY READER

1953: Brave New World

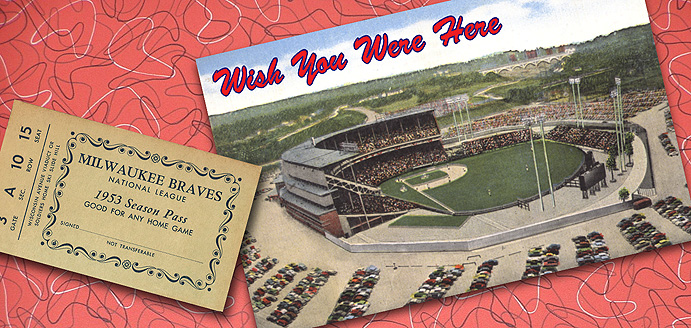

The Braves become the first team in 50 years to relocate, ending up in Milwaukee where attendnce jumps six-fold; the team responds by improving dramatically in the standings. Envious baseball owners elsewhere sit up and take notice.

For half of a century, the geographical landscape of major league baseball stood still. Not since the replacement of the Baltimore Orioles with a New York team in 1903 had any big league franchise relocated, perished or been born. The same 16 teams representing the same 10 cities, all from the northeast quadrant of America, consistently went about their business with one another. Change, expansion or contraction was deemed unnecessary as a comfortable status quo was maintained.

But a fast track of progress in postwar America began to strain baseball’s comfort zone. Air travel, television, the automobile and suburbia were quickly transforming the 48 states into a smaller, reachable and more affordable society. Emerging markets around the country bloomed like blue-chip prospects, making pitches to bring major league baseball to town; the owners initially paid lip service yet remained content, even as their aging ballparks became more engulfed by accelerated inner-city decay.

During the winter of 1953, two owners seriously took heed to what the new frontier had to offer. Bill Veeck, who presided over a wildly successful yet brief reign at Cleveland, was now having the most difficult mission of his baseball life: Convincing people to see his latest asset, the sad-sack St. Louis Browns, in a city where only the Cardinals were considered real baseball entertainment. Meanwhile in Boston, Lou Perini had witnessed a stunning fall from grace for his Braves. In four years, the team deteriorated from National League champions to distant second division material, and its attendance plunged even worse—from 1.5 million to a scant 280,000. Competing head-on with the prestigious Red Sox was a task Perini wanted nothing more to do with.

The Demise of the Boston Braves

Over their last five years in Boston before relocating to Milwaukee, the Braves completed an intense downward spiral that began with a NL pennant and ended with a seventh-place finish, minuscule crowds and a call to Wisconsin.

Both Veeck and Perini wanted out, but they wanted to go to the same city: Milwaukee. Veeck ran the minor league Brewers there with success in the 1940s, and knew about the city’s potential to embrace the majors. But Perini held the territorial rights to the region, giving him a critical leg up in his quest to bring over the Braves. A new publicly built ballpark waited in the wings.

The battle was over before it began. Besides the territorial rights, Perini had one other big weapon: The other owners, who always saw Veeck as a rogue who wasn’t one of them, and wanted him out of baseball.

In mid-March, two weeks after successfully lobbying to block Veeck’s move to Milwaukee, Perini publicly announced his own intentions to move the Braves; within a week, the owners granted him his wish. Warming up for the season in Florida, Braves players still wearing caps displaying “B” for Boston were stunned by the events and scrambled to find new housing in Milwaukee. Back in Boston, few fans cried over the loss of 77 years of National League baseball.

Outmaneuvered, Veeck was chained to St. Louis for another year. The Browns would go on to lose 100 games, again, and draw less than 300,000. If Veeck couldn’t go to Milwaukee, he’d try somewhere, anywhere, to move the Browns. So at the end of the year he asked the lords for a move to Baltimore. They said no. Tired, desperate and out of options, Veeck sold the Browns. The new owners quickly got what Veeck was denied: A move to Baltimore.

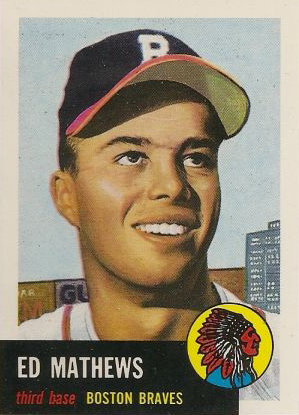

As attendance in Milwaukee exploded for the Braves, so did the numbers of second-year third baseman Eddie Mathews, who clobbered 47 home runs with a .302 average in 1953.

The Milwaukee Braves quickly dispelled any lingering doubts that major league baseball could play in new arenas. A crowd of 34,000 jammed barely-completed County Stadium for its first home game on a cold and drizzly Wisconsin day. They continued to fill the park, again and again. It took just 13 home dates for the Braves to surpass their total 1952 attendance at Boston.

Like wayward kings worshiped in a new kingdom, the Braves responded to the adoration and won 18 of their first 24 home games—and vaulted into first place, where they stayed well into June. Not bad for a team that lost 90 the year before.

The Braves were a team full of individual highlights. Veteran pitcher Warren Spahn would lead the NL with 23 wins and a 2.10 earned run average. Bill Bruton, a rookie outfielder with veteran knowledge of Milwaukee—where he spent 1952 as a minor leaguer—stole a league-high 26 bases. Most impressive of all was the monster performance of 21-year-old third baseman Eddie Mathews, who in his second big league year led the NL with 47 home runs while batting .302 with 135 runs batted in.

BTW: Mathews would ultimately be the only player to play for the Braves in Boston, Milwaukee and Atlanta.

All that got in the way of the Braves achieving the ultimate fairy tale were the Brooklyn Dodgers.

Hardly intimidated by big crowds, the Dodgers won their first six games at Milwaukee, stealing first place away and contributing to a nine-game Braves losing streak to end June. Brooklyn sped away after the All-Star break and never lost more than two in a row the rest of the season, on its way to a 105-49 record—the best in Dodgers franchise history. Adding insult to injury, the Dodgers clinched the NL flag on September 12 with a win at Milwaukee against the Braves.

BTW: The 2019 Dodgers would win 106 games, but because they played eight more games had a lower winning percentage.

Offensively, the Boys of Summer prospered as a powerhouse in full bloom. Not only did the Dodgers lead the NL in every major hitting category, none of the other teams came close. Leading the titanic assault was Duke Snider (.336 batting average, 42 home runs, 126 RBIs) and Roy Campanella (.312, 41, 142)—the first duo from any NL team to each hit over 40 homers. Gil Hodges added 31 round-trippers and 122 RBIs while batting .302. And for outfielder Carl Furillo, offseason eye surgery was obviously successful; he earned the league batting title at .344 a year after hitting a hundred points lighter.

On the mound, the Dodgers’ pitching staff was solid and stable enough to hold the big leads built up by the offense, though it clearly was not the team’s strength. Carl Erskine won 20 of 26 decisions and continued to be the substitute ace in the absence of Don Newcombe, wrapping up his two-year tour of duty with the armed forces in Korea.

The race for the American League pennant was no less predictable. None of the seven AL teams outside of New York could even dance with the Yankees. A 41-11 start, highlighted by an 18-game win streak and a memorably monstrous 565-foot home run at Washington by Mickey Mantle, gave the Yankees a 10-game lead before summer heated up.

BTW: Ironically, the Yankees’ 18-game win streak was snapped by the St. Louis Browns, who ended their own string of 14 straight losses.

The Yankees maintained first place to the finish, absorbing a nine-game losing streak in June that particularly ticked off manager Casey Stengel. After a series of admonishments by the skipper, normalcy returned and the Yankees were able to glide to an early clinching date on September 14.

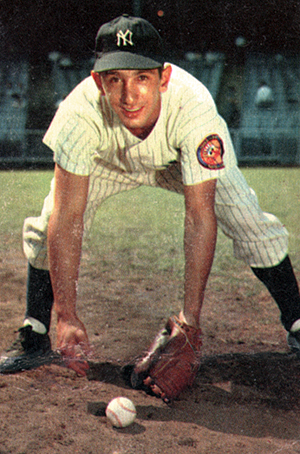

Yankees second baseman Billy Martin, who would hit .333 with five home runs in 28 career World Series Games, had his best Fall Classic performance in 1953—collecting a then-record 12 hits against Brooklyn. (The Rucker Archive)

Closest to the Yankees among the would-be’s were the Cleveland Indians, who once again showed more impressive individual numbers but lacked the balance and flexibility to overcome the Yankees. Third baseman Al Rosen’s spectacular MVP effort (.336 average, 43 home runs, 145 RBIs) jumped out from a list of otherwise standard team batting achievements.

It’s often been said that a World Series can’t be won without pitching and defense. Impressive as Brooklyn’s bats were during the season, its team ERA was a full run worse than the Yankees. This, along with some painful defensive play, would badly hurt the Dodgers in their Series rematch with New York.

The Yankees took the first two games at home by scores of 9-5 and 4-2, buoyed by four home runs and perfect defense while the Dodgers committed three errors. Back at Ebbets Field, Brooklyn pitching rose to the occasion; Carl Erskine broke Howard Ehmke’s Series strikeout record with 14 in Game Three to win 3-2, and Billy Loes nearly went the distance in a 7-3 Game Four victory.

The Dodgers saved their most potent attack for a pivotal Game Five at Ebbets—scoring seven runs on 14 hits, including two home runs—but the pitching couldn’t keep the Yankees in check. Mickey Mantle’s grand slam in the third inning was crushing from a physical point of view—it reached Ebbets’ upper deck in left center—and from an emotional one as well, giving the Yankees a 6-1 lead in an eventual 11-7 victory. Game Six sealed the Dodgers’ fate, as Billy Martin’s run-scoring, record-tying 12th hit of the Series broke a 3-3 tie in the bottom of the ninth to give the Yankees the Series at Yankee Stadium.

In defeat, the Dodgers hit as well as they had all year—batting .300 with eight home runs in six games—but the 4.91 team ERA was, as the scouting report warned, their Achilles’ heel. Brooklyn’s fielding certainly lent no help, committing seven errors while the Yankees botched up just once.

We Looked it up, Casey

Although the Yankees won an unprecedented fifth straight World Series title, their collective dominance paled on paper compared to similar Yankee reigns during the 1920s, late 1930s and 1990s. What ultimately separated New York from their NL challengers from 1949-53 was timely hitting, a bit more power—and, of course, better pitching.

The Yankees may have reigned supreme on the field for a record fifth straight time, but it was the Milwaukee Braves who won at the box office. They drew a NL-record 1,826,000 fans in their first year, the first of six straight seasons in which it would lead the majors in attendance. The Milwaukee phenomenon wasn’t enough to give the Braves a World Series title—yet—but the consolation prize for Lou Perini was that he was the happiest man in baseball.

At Dodgers headquarters in Brooklyn, owner Walter O’Malley was less concerned about losing yet again to the Yankees as he was concerned over what the Milwaukee Braves represented. Yes, the Dodgers had disposed of the Braves with relative ease—on the field. But to O’Malley, a crafty man with vision, he saw in Milwaukee a market with hungry fans, a modern ballpark with lots of parking and new forms of revenue streams—little of which he could offer at aging, congested Ebbets Field. O’Malley sensed, in this off-the-field battle, that he ultimately could beat the Braves at their own game.

He just wasn’t sure he could do it in Brooklyn.

Lou Perini and the Braves had opened a Pandora’s Box from which the new culture of baseball emanated. After 50 years of happily standing pat, the sport would embark on a wild ride of franchise movement and expansion that, over the next two decades, would result in a total of 10 relocations and eight new ballclubs.

Forward to 1954: At Least They Stopped the Yanks The Cleveland Indians go titanic and put a halt to the New York Yankees’ five-year American League reign—but they fall short of a world title in October.

Forward to 1954: At Least They Stopped the Yanks The Cleveland Indians go titanic and put a halt to the New York Yankees’ five-year American League reign—but they fall short of a world title in October.

Back to 1952: The Education of Mickey Mantle How the next in line to inherit the throne as the New York Yankees’ icon nearly caved under the pressure.

Back to 1952: The Education of Mickey Mantle How the next in line to inherit the throne as the New York Yankees’ icon nearly caved under the pressure.

1953 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1953 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1953 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1953 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1950s: A Monopoly of Success Though described as a golden age for baseball, most major league teams find themselves struggling—unless you’re in New York City, where the Yankees, Dodgers and Giants hog the World Series podium from 1950-56. But as the decade winds to a close, the euphoria of Big Apple baseball will rot overnight.

The 1950s: A Monopoly of Success Though described as a golden age for baseball, most major league teams find themselves struggling—unless you’re in New York City, where the Yankees, Dodgers and Giants hog the World Series podium from 1950-56. But as the decade winds to a close, the euphoria of Big Apple baseball will rot overnight.

Gus Zernial talks of posing with Marilyn Monroe, being snubbed by Casey Stengel and striking out (often).

Gus Zernial talks of posing with Marilyn Monroe, being snubbed by Casey Stengel and striking out (often). Bill Renna recalls his rookie year with the 1953 New York Yankees and how he tip-toed around the veteran stars to get along in the clubhouse.

Bill Renna recalls his rookie year with the 1953 New York Yankees and how he tip-toed around the veteran stars to get along in the clubhouse. Art Schallock fondly recalls his time spent with the championship-caliber Yankees of the early 1950s, how he owned Ted Williams, and the state of the game today.

Art Schallock fondly recalls his time spent with the championship-caliber Yankees of the early 1950s, how he owned Ted Williams, and the state of the game today.