THE YEARLY READER

2019: The Pill of Might

Home run records fall like dominoes as skeptical fans, angry pitchers and an oblivious MLB grapple over if a juiced ball is to blame.

(Flickr—KA Sports Photos)

It’s often said that records are made to be broken. Anyone who owns a baseball record book understands; it’s usually outdated within a couple years after its publication.

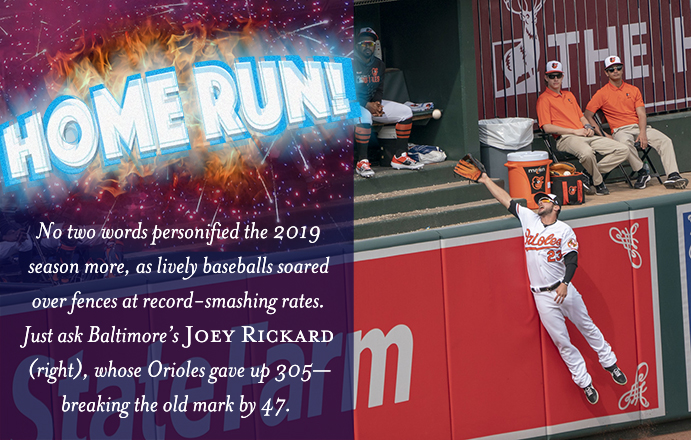

For some baseball fans, it thus didn’t sound remarkable when, during the 2019 season, the Minnesota Twins reset the all-time season team mark for home runs—while the Baltimore Orioles broke the record for the most homers allowed in a year. After all, the records they erased were hardly longstanding; the old mark of 267 surpassed by the Twins was set just a year before, while the Orioles couldn’t avoid passing a mark that itself had stood for only three years.

So while all of that may not have sharply turned heads, this did: The Twins and Orioles set their records in late August—with a full month of the season still to play.

Raising the bar on home run totals is hardly anything new. A certain season is declared The Year of the Home Run, until it gets voided by the next Year of the Home Run, which then bows to yet another. The 1961 season, highlighted by Roger Maris’ 61 homers, gave way to 1969 and a power spike augmented by the lowering of the pitching mound, which gave way to 1977 and a then-rare 50-homer effort by George Foster, and finally to 1998 when Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa individually blasted past Maris.

In each of those cases, expansion was to blame; new teams meant more pitchers who a year earlier weren’t good enough to be major leaguers—and were thus taken advantage of by the likes of Maris, Foster, McGwire and Sosa. But the 2019 season involved no new teams, no new flock of sheep to be skinned by veteran sluggers. Same teams, same players—and a different, more lively ball. The vast preponderance of home run records set in 2019—and the remarkable ease and rapidity in which they were broken—made people wonder: Would this new Year of the Home Run remain the year for ages to come, the way 1968’s Year of the Pitcher remains so over 50 years later?

From the word go, it was quite apparent that the 2019 regular season would be a banner one for sluggers. The first of a cavalcade of home run records were set on Opening Day when 48 balls rocketed over the fence; 10 of them alone would be cranked out in a game between the Los Angeles Dodgers and Arizona Diamondbacks, setting another first-day mark. On the second day, St. Louis’ Paul Goldschmidt—playing his second game for the Cardinals after eight years with the Diamondbacks—enjoyed the first of a record-tying 22 three-homer performances by major leaguers on the year. By the end of April, the beleaguered Orioles—coming off a 47-115 campaign the year before—surrendered 69 jacks, snapping the mark for the most allowed in a single month. The Orioles would also give up at least five deep flies in six games during the month; the record for an entire season was nine. Eventually, the Orioles would blow right past the mark and give up five or more in 19 games. It was as if the batting practice pitchers had taken over to serve up one bleacher souvenir after another.

BTW: The Miami Marlins would tie the Orioles’ monthly mark later in August.

For the first time ever, over a thousand home runs were hit in April. In May, the 1,135 homers hit were the most for any month, ever. Then came June—and another reset, at 1,142. And then that got toppled two months later, when 1,228 sailed over the fence in August. In fact, by the end of the 2019 season, new records were set for every month. Grand total for the year: 6,776 home runs—an 11% increase over the previous season high of 6,105, set in 2017.

Shellshocked pitchers demoted to the minors would not find any safe spaces. Both Triple-A leagues (Pacific Coast, International), using the same ball as the majors for the first time ever, saw a radical 61% jump in home runs over the previous year.

So why was their so much sudden life in the baseball? The answer may lie in a move made by Major League Baseball a year earlier, when they joined a private equity firm to buy Rawlings, manufacturer of the official MLB ball. At the time, MLB executive vice president for strategy Chris Marinak perhaps foretold the future when he said that MLB was “particularly interested in providing even more input and direction on the production” of the ball. Apparently, that input was quite juicy.

During the 2019 All-Star Break, commissioner Rob Manfred fessed up—sort of. In an interview with Newsday, Manfred said the culprit for skyrocketing home run totals was a “pill” in the middle of the ball that, he said, Rawlings was getting better at centering. The theory went that the more centered the pill, the less drag the ball created—and thus the further it went.

Pitchers may have agreed, but they were skeptical to accept Manfred’s innocent shrugging of his shoulders. Houston ace Justin Verlander didn’t mince words: “(The ball) is a f**king joke,” he told ESPN’s Jeff Passan. “They own (Rawlings)…We all know what happened. We’re not idiots.” Alex Cobb, one of those besieged by opposing boomers in Baltimore, told the Washington Post, “I’m amazed the question is even being asked.” The hitters, meanwhile, didn’t have much to say. They were too busy rounding the bases.

Live Yard or Die Trying

A definite trend within the majors that led to 2019’s Year of the Home Run was what’s become known as the “three outcomes”—a scenario in which the batter is increasingly likely to strike out, walk or hit a home run. The decade-by-decade chart below, representing the whole of baseball’s modern era, reflects the three outcomes’ growing influence upon the game.

The nonstop assault on the record book continued past the All-Star Break. Not surprisingly, the Orioles led the way in the best and (mostly) worst of ways. In late July, they set an all-time mark by hitting at least two home runs in 10 straight games. Right on the heels of that achievement, they started a new streak—consecutive games allowing two or more homers. That run, which ended at 12 games, set another record.

No team took advantage of the combination of the perfectly centered pill and the Orioles’ sad state of pitching more than the New York Yankees. In 19 total games against the Orioles—17 of which the Yankees won—the Bronx Bombers teed off on helpless Baltimore hurlers with 61 total homers to forge a smile from the ghost of Roger Maris. Of those 61, 43 were hit in 10 games played at Baltimore’s home yard, Oriole Park at Camden Yards. This New York tsunami of taters, a good chunk of which were hit in August, helped the Yankees collect a whopping 74 for the entire month. The three numbers listed above—61 against one team, 43 at an opposing ballpark and 74 for one month—didn’t just break records; they annihilated them. The old records, respectively: 48, 29 and 58.

When the Yankees’ year-old season mark of 267 was broken by Minnesota on August 31, the question was not how many more the Twins would hit to extend the record total, but whether they would even own the record at year’s end. The Yankees, thanks to their demolition of the Orioles, were hot on their tails; not surprisingly, when the two teams earlier met in July at Minneapolis, they combined to belt 20 homers—tying the AL mark for the most in a three-game series. At year’s end, however, the Twins barely prevailed as the all-time record-holder, powering out 307 to the Yankees’ 306 on the strength of five Twins hitting at least 30—another unprecedented feat.

Ironically, in a season gone mad with power, nobody came close to Barry Bonds’ individual season mark of 73, as New York Mets rookie Pete Alonso paced all major leaguers with 53. (Alonso did, however, break Aaron Judge’s rookie mark from 2017.) But 58 different players hit at least 30—more than double the 27 who did it a year before. One theory, perhaps bathed in conspiracy, as to why Bonds’ record remained easily secure amid the power surge came from no less an authority than Victor Conte, founder of the shuttered BALCO steroids lab that infamously counted Bonds as a client. Conte claimed that many major leaguers were still taking steroids, but had become wise to MLB’s PED testing routine—knowing how much to consume and when to not get caught. In other words, to be content with 30 or 40 homers and not a sackful more to keep the floodlights of MLB’s steroid police off them.

If Conte’s belief was true, it only makes one pause to think just how many more home runs would have been hit in 2019. By season’s end, the carnage was complete enough, with half of MLB’s 30 teams either breaking or tying their all-time season marks for homers. Rob Manfred now had to ask himself the same question all his predecessors had asked after all those other Years of the Home Run: Has this all become too much of a good thing?

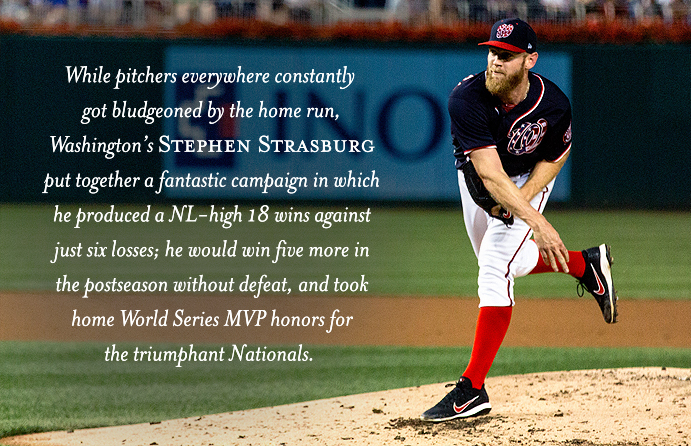

Too much of a bad thing had been the story of the 2010s for the Washington Nationals—bad, that is, when they reached the postseason. The Nationals were constantly good in the regular season, winning more games during the decade than all but three teams (Yankees, Dodgers and Cardinals) with a roster built behind slugger Bryce Harper and ace Stephen Strasburg, the team’s 1-2 punch of #1 draft picks-turned stars. But the Nationals failed to leverage the triumphant vibe into the playoffs, losing all four postseason series in which they appeared; three of those defeats ended in a decisive fifth game in which the Nationals led in each. It was a microcosm of a bigger trend for the franchise, which hadn’t won a playoff series since their days as the Montreal Expos nearly four decades earlier.

Being stung by October failures was bad enough karma for the Nationals. Worse, they entered 2019 feeling handicapped to boot after losing Harper in free agency to NL East rival Philadelphia. Then things got really ugly; the Nationals started the season at 19-31 thanks to a bullpen that couldn’t do anything right. It cost Washington pitching coach Derek Lilliquist his job; rumor had it that second-year manager Dave Martinez was next.

From that low point, the Nationals began to bounce back—because their roster was just too good to remain stuck near the divisional cellar. Within six weeks, they were back at .500, and followed that stepping stone with another when their rotation—highlighted by Strasburg, fellow hard-throwing ace Max Scherzer and first-year National Patrick Corbin—went 27 straight games without a loss; the team won 20 of those games, with a still iffy bullpen getting charged for all seven losses. Then in August, the offense took over—hitting .292 for the month while averaging over 10 runs per contest in one seven-game stretch.

BTW: The Nationals’ 27-game undefeated streak by starting pitchers was the majors’ longest since the 1916 New York Giants.

(Flickr-Laurie Shaull)

With each passing week, Washington strengthened on the field and in the standings; by mid-September, the Nationals took command of the NL wild card race and clinched the spot, all too poetically, when they swept a doubleheader from Harper’s Phillies in the season’s final week. The Nationals’ 93-69 regular season mark was all the more impressive given that they were 74-38 following their late-May nadir.

Individually, the Nationals were a well-balanced representation of quality output. Third baseman Anthony Rendon blossomed into perfectly-timed MVP form as free agency loomed, batting .319 with 34 home runs and a major league-leading 126 runs batted in. Matching Rendon on the home run counter was sophomore outfielder Juan Soto, who at the tender age of 20 exhibited a remarkable combination of power and patience (108 walks) that led to daily Twitter stat accounts comparing his youthful rise to that of Mel Ott 90 years earlier. Speedster Trea Turner stole 35 bases, while 22-year-old rookie outfielder Victor Robles swiped 28 more. From the bench, veteran Howie Kendrick was frequently plugged in wherever needed and hit .344 over 334 at-bats. On the mound, Strasburg (18 wins, six losses, 3.32 earned run average and 251 strikeouts), Scherzer (11-7, 2.92, 243) and Corbin (14-7, 3.25, 238) became the first-ever trio of pitchers from the same team to strike out at least 225. And even the maligned bullpen got its act together toward season’s end, with stabilization from closer Sean Doolittle (29 saves) and true relief from Daniel Hudson, who posted a 1.44 ERA over 24 games after being picked up from Toronto.

The regular season behind them, the Nationals now came face-to-face with what had been, historically, the hard part: Winning in the postseason. And in what would be a parallel to the year to date, the Nationals would play the comeback kids, spotting opponents the advantage before stealing it away. It would be a nice, swift about-face from previous years of postseason woe.

In the NL Wild Card game against Milwaukee—a potent side fronted by star outfielder Christian Yelich, until he suffered a season-ending broken wrist in early September—the Nationals trailed the whole way at home into the eighth inning. But a 3-1 deficit was erased in the bottom half of that frame when Soto’s soft liner to right eluded rookie outfielder Trent Grisham—subbing in for Yelich—to score the eventual game-winner. It was the first time the Nationals won a winner-take-all playoff game since 1981.

A much tougher task lay ahead for Washington in the NLDS, facing off against the Dodgers. To say the odds didn’t favor the Nationals was an understatement; Los Angeles won a franchise-record 106 games, set a NL record with 270 home runs, and fielded league MVP Cody Bellinger (.305 average, 47 homers and 115 RBIs) and ERA leader Hyun-Jin Ryu (2.32). And when the Dodgers won two of the first three games by an aggregate score of 18-8, the Nationals once more got that sinking feeling of imminent playoff departure.

After staying alive with a 6-1 Game Four victory behind Scherzer, the Nationals returned to Los Angeles for the decisive fifth game and, as they did against Milwaukee, entered the eighth inning trailing, 3-1. And, as they did against Milwaukee, they countered—this time more improbably, with back-to-back solo homers from Rendon and Soto off of veteran Dodgers ace Clayton Kershaw, making a rare relief appearance. Tied after nine innings, the Nationals leveled a shocking blow in the 10th when Howie Kendrick blasted a grand slam against reliever Joe Kelly to forge a 7-3, series-winning upset. Riding the exaltation of triumph over the Dodgers, the Nationals quickly grounded the NL Central-winning Cardinals in four straight at the NLCS.

One huge hurdle was cleared for the Nationals by expelling the favored Dodgers and Cardinals. Another lay ahead in the World Series against an even more dominant team: The Houston Astros.

In an American League where parity continued to be a lost concept—for the second straight year, nine of 15 AL teams won or lost 95-plus games—the Astros prevailed as the mightiest of the mighty, by the record and through October. A prodigious offense led the majors in bat average (.274), on-base percentage (.352) and slugging percentage (.495) while smacking 288 home runs—third highest on the year and, in this Year of the Home Run, third highest ever—with seven players hitting at least 20. Among them were usual suspects in lead-off masher George Springer (39 home runs over 122 games) and pint-sized infielder Jose Altuve (31 homers in 124 games), while infielder Alex Bregman emerged as a legitimate MVP candidate with a .296 average, 41 homers, 112 RBIs and 119 walks. But there were pleasant surprises adding their names to the list; outfielder Michael Brantley, the oft-injured former Cleveland star, managed to stay healthy in his first year at Houston with 22 jacks and a .311 average, while at midseason the Astros called up bruising 22-year-old Yordan Alvarez, who led the minors with 23 homers—and added 27 more with a .313 average in 87 games for Houston, earning AL Rookie of the Year honors.

Easily holding up an otherwise thin Houston rotation was a pair of aces: Right-handers Justin Verlander and Gerrit Cole. The 36-year-old Verlander continued to live a late-career renaissance, winning a major league-best 21 wins against just six losses while posting a 2.58 ERA that was second in the AL; first place was reserved for Cole, whose 2.50 figure along with a 20-5 record was the product of an electric fastball (averaging 97.2 MPH) mixed with a combination of nasty off-speed deliveries. After losing at Chicago against the White Sox on May 22, Cole went undefeated for the rest of the regular season, going 16-0 in 22 starts with a 1.78 ERA; he struck out at least 10 batters in each of his last nine starts, setting an MLB record within one season. Overall, Cole struck out 326 batters—the most by an AL pitcher in over 40 years—while Verlander collected an even 300 Ks.

After a blasé start by their standards, the Astros took hold of first place in the AL West by the end of April and never looked back, storming to a franchise-best 107-55 record on the strength of 60 home wins and a blistering 56-20 mark against divisional opponents. The AL playoffs proved less of a breeze; Houston sweated out a five-game ALDS triumph against a pesky Tampa Bay side sporting the majors’ lowest payroll, and was taken to a sixth game in the ALCS against the equally high-powered Yankees, clinching their second AL pennant in three years by overcoming a ninth-inning New York rally with one of its own on Altuve’s two-run, two-out walk-off shot against Yankees closer Aroldis Chapman.

Houston Clubhouse Confidential

The Astros’ locker room became a source of numerous controversies during the 2019 campaign. In August, outspoken Houston ace Justin Verlander, at odds with Detroit Free Press reporter Anthony Fenech over a years-old article, told the front office to bar him from the clubhouse while the Tigers were visiting; the Astros obliged, to the chagrin of the Baseball Writers Association of America—which charged the Astros with violating Basic Agreement rules.

In an even uglier scenario that took place moments after the Astros won the AL pennant, Houston assistant general manager Brandon Taubman approached three female sportswriters in a celebratory Astros clubhouse and repeatedly yelled out, “Thank God we got (closer Roberto) Osuna!”—occasionally sprinkling in a profanity. It was a confusing and creepy outburst all at once; Osuna, picked up by Houston a year earlier after being charged with domestic abuse, had given up a game-tying homer to the Yankees’ DJ LeMahieu before the Astros countered in the bottom of the ninth. The Astros at first denied the report and, worse, cast the female witnesses as liars—but were forced into an embarrassing about-face once too many corroborated the sequence, apologized and fired Taubman.

Finally, after the World Series, allegations surfaced of the Astros using one or more elaborate schemes to cheat their way to the 2017 pennant and perhaps beyond, leading to an MLB investigation that would publicly dominate the offseason to come.

No team all season had defeated Verlander and Cole in back-to-back games—and the Astros never lost any of 28 games in which they scored at least twice in the first inning. The Washington Nationals shrugged, “So what?”

In World Series Game One, the Nationals spotted Cole and the Astros a 2-0 deficit after an inning before scoring five unanswered runs, including solo homers from Juan Soto and Ryan Zimmerman—a member of the Nationals every year since their move from Montreal in 2005. In Game Two, a 2-2 tie remained until the seventh when Washington broke through for six runs—the first two off of Verlander, leading to his exit—to run away with a 12-3 rout.

The Astros, down two games with the next three at Washington, appeared to be in big trouble. But then it became their turn to play the road warriors. With late-season pick-up Zack Greinke, rookie spot starter Jose Urquidy and Cole clamping down, Houston won all three games at Nationals Park—allowing just a run in each. Suddenly, the Astros returned to Houston with two games to win one.

And the Nationals, who’d been playing from behind all year, had the Astros just where they wanted them.

Trailing again after the first inning in Game Six, the Nationals bounced back against Verlander and Company, notching six runs—five off the bat of Anthony Rendon—to secure an easy 7-2 victory, as Stephen Strasburg became impenetrable after a rocky start. In the decisive Game Seven, Greinke had the Nationals locked down through six easy innings as Houston grabbed a 2-0 lead—but after Rendon homered and Soto walked with one out in the seventh, Houston manager A.J. Hinch played the kneejerk reactor and replaced Greinke with Will Harris, Houston’s toughest reliever during the year.

BTW: Verlander dropped to 0-6 in seven career World Series starts; no other pitcher has lost more in the Fall Classic without a win.

Except, that is, on this night.

The first batter facing Harris, one Howie Kendrick—he of the NLDS heroism against the Dodgers—struck again at just the right moment, tagging an opposite-field liner off Minute Maid Park’s right-field pole to give the Nationals a 3-2 lead. Patrick Corbin, used more crucially as a reliever during the postseason, easily stifled any Houston counterattack with three shutout frames—and with three additional runs of insurance, the Nationals pulled away with a 6-2 win. It was the first World Series triumph in 51 years of Expos/Nationals history, the first for a Washington-based team since the Senators beat the Giants in seven games 95 years earlier—and the first time every game of a Fall Classic was won by the road team.

BTW: Only one other team had, at one point during the year, fallen more games below .500 before winning it all: Boston’s “Miracle” Braves of 1914.

In December 2019, an independent study was released on just why the ball was jumping out of ballparks at a record rate. Four scientists concluded that there was a decrease in drag, but didn’t mention Rob Manfred’s “pill” at the center of the ball. They also determined that part of the increase was due to the players themselves, who were mastering the art of the “launch angle” to send balls higher and deeper into orbit. But they found no smoking gun, no nefarious schemes to intentionally liven up the ball. Some fans and media were skeptical about the “independent” nature of the report, given that it was commissioned—and thus potentially controlled—by Manfred and MLB.

For the conspiracy theorists, there was further argument to be taken up that MLB wanted the ball spiked and, when it achieved its objective, found it had gone a little too far. Perhaps that explained why the ball seemed less lively in the postseason, as participating players openly questioned why the ball that they were pounding over the fence during the regular season was suddenly being caught at the wall. The truth is that postseason home run rates were down only 4% from the regular season, but reality has a way of being exaggerated into perception.

Thus ended the latest Year of the Home Run. Until the next one comes along…if it ever does.

Forward to 2020: Pandemicmonium Baseball endures the unexpected challenge of trying to wring out a season as a largely unchecked pandemic rages through America.

Forward to 2020: Pandemicmonium Baseball endures the unexpected challenge of trying to wring out a season as a largely unchecked pandemic rages through America.

Back to 2018: Wrenching With Tradition The advent of the opener threatens to accelerate the devolution of the starting pitcher as Baseball ponders rule changes in response.

Back to 2018: Wrenching With Tradition The advent of the opener threatens to accelerate the devolution of the starting pitcher as Baseball ponders rule changes in response.

2019 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 2019 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

2019 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 2019 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 2010s: A Call to Arms Stronger and faster than ever, major league pitchers restore the balance and then some—yet despite the decline in offense and rise in strikeouts, baseball continues to bring home the bacon through its lucrative online and regional network engagements.

The 2010s: A Call to Arms Stronger and faster than ever, major league pitchers restore the balance and then some—yet despite the decline in offense and rise in strikeouts, baseball continues to bring home the bacon through its lucrative online and regional network engagements.