THE YEARLY READER

1959: Reinventing Dodger

The team formerly known as the Brooklyn Dodgers returns to top form in Los Angeles and survives a frenzied NL pennant race to take the World Series over the Chicago White Sox, who are putting the strategy of speed back into baseball.

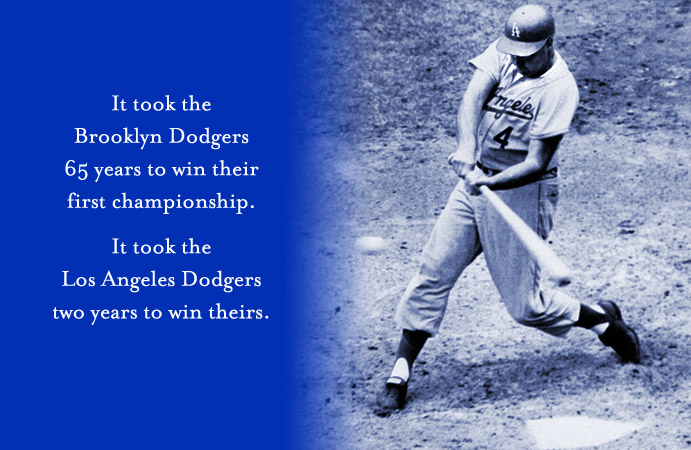

Duke Snider, one of the Dodgers’ aging Boys of Summer, puts a youthful jolt into a home run that opens the floodgates for Los Angeles in the decisive sixth game of the 1959 World Series at Chicago against the White Sox. (Associated Press)

While fans in Los Angeles weren’t stuck with a woebegone reject from another time—like, say, the St. Louis Browns—or an expansion unit obligated to take a pounding from veteran teams, the Dodgers club that came to town wasn’t exactly a well-oiled, pre-assembled champion, either. The team’s first year in Los Angeles resembled an extended lost weekend in which the aging Boys of Summer, previously ingrained within the tight-knit Brooklyn neighborhood, had become lost tourists trying to find their footing in an endless coastal valley attired in palm trees, freeways and theme parks. This cultural shock, further complicated by a home field wedged into a football stadium, reduced the Dodgers to a struggling bunch that finished just two games out of the National League cellar in 1958.

Faded dreams of instant World Series glory gave way to revived hopes for the City of Angels in 1959, as a flurry of adjustments—to say nothing of increased acclamation to their new surroundings—led the Dodgers back to the Fall Classic against a Chicago White Sox team that had rediscovered the lost art of winning with speed.

Any notion of the Dodgers clinging to yesteryear’s grandeur was quickly dismissed as the team’s 1959 roster developed and gelled during the season. The everyday lineup included only three players—Duke Snider, Gil Hodges and Jim Gilliam—who were regulars back at Brooklyn. Gone or almost gone were Pee Wee Reese and Jackie Robinson (retired), Don Newcombe (traded), Carl Furillo and Carl Erskine (aging and benched), and Roy Campanella (forever confined to a wheelchair after a tragic car accident). Second baseman Charlie Neal and pitcher Don Drysdale had emerged before the move to Los Angeles, but barely figured in Ebbets Field history.

Players who never wore the Brooklyn uniform were thriving as key additions in Los Angeles, and would help the Dodgers progress successfully through 1959. Acquired from St. Louis was left-handed slugger Wally Moon, who perfected opposite-field home runs—called “Moon Shots”—hit to the short left-field netting at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum. Speed burner Maury Wills took over as the everyday shortstop by midseason. Reliever and spot starter Larry Sherry, a Los Angeles native, easily felt at home as he joined the club at midseason and won seven of nine decisions with three saves and a 2.20 earned run average.

BTW: Moon hit 19 home runs in all, to go with a .302 batting average, a league-high 11 triples and 15 stolen bases.

The Dodgers warmed up through the early summer in a tight dogfight with two-time defending NL champs Milwaukee and San Francisco. They finally captured first place at the end of July, but quickly lost it when Giants rookie Willie McCovey said hello to the majors and gave San Francisco a brief but important boost, one that kept them on top of the standings well into September.

BTW: McCovey’s major league debut on July 30 was a 4-for-4 performance, including two triples, against Philadelphia’s Robin Roberts.

Two games behind the Giants and tied with the Braves for second place going into the season’s penultimate weekend, the Dodgers faced a tough mission: Playing their final eight games on the road, starting with three at San Francisco. Their clutch game in high gear, the Dodgers swept the Giants in a Saturday doubleheader, then coasted to an 8-2 Sunday win to sweep the series—spinning the Giants into a season-ending dizzy spell for which they would lose seven of their last eight games. The Braves were consumed by no such slump and virtually went neck-to-neck with the Dodgers to the wire, the two teams wrapping the regular season schedule with identical 86-68 records.

Having lost the last two tiebreaking, best-of-three series to settle the NL pennant—most recently in heartbreakingly historic fashion to the Giants in 1951—the Dodgers set out to do whatever it took to avoid a hat trick of defeat. It wasn’t easy. Larry Sherry had to pitch 7.2 innings of scoreless relief to bail the Dodgers out of the first game at Milwaukee, 3-2, after trailing early. Back at Los Angeles for the second game, the Dodgers overcame a three-run deficit in the ninth inning and, in the 12th, throwing error by Braves shortstop brought home the winning run—and the Dodgers’ first Los Angeles pennant.

BTW: A third game would have matched the Dodgers against Milwaukee’s Bob Buhl—a noted Dodger killer who was 6-0 against Los Angeles in 1959.

The Worst of the Best

Before divisional play, expanded playoffs and wild cards dummied up the postseason field with occasional participants barely above .500, the Dodgers’ 88-68 mark topped the list of those teams who won pennants outright with lowly records.

It was a small wonder that the Milwaukee Braves didn’t take the NL outright with ease. Hank Aaron (.355 batting average, 39 home runs, 123 RBIs) and Eddie Mathews (.306, 46, 114) were on fire, while Warren Spahn and Lew Burdette each won 21 games. But the Braves lacked consistency in their lineup, and unlike the Dodgers, could not avoid the injury bug—most notably with second baseman Red Schoendienst missing the entire season battling tuberculosis.

At 88-68, the Dodgers would own the worst pennant-winning record in baseball before the leagues split into divisions in 1969, but after their abysmal Los Angeles debut in 1958, a pennant was a pennant was a pennant.

While the Dodgers returned to the NL throne, the American League witnessed what most fans of the time might have equated with the 100-year flood: A major pratfall by the New York Yankees.

Like the Dodgers of 1958, the Yankees of 1959 were brought down by a combination of subpar performances (from Mickey Mantle and pitcher Bob Turley) and aging players (Yogi Berra, Hank Bauer) whose best years were well behind them. The four-time defending AL champs started miserably—at one point in late May, they were briefly stationed in last place at 12-20—and recovered only well enough to bounce around the .500 mark. Their final record of 79-75 was their worst showing in 34 years.

BTW: Turley, the 1958 Cy Young Award winner, collapsed with a dying fastball that resulted in an 8-11 record and 4.52 ERA.

The door to the AL pennant was thus left wide open for two teams pent up with a decade’s worth of utter frustration trying to upstage the Yankees: The Chicago White Sox and Cleveland Indians.

Bill Veeck, last seen being run out of baseball by his fellow owners when he couldn’t move the Browns out of St. Louis in 1953, had snuck his way back in as the White Sox’ new owner after a family feud within the Comiskey family imploded and left the franchise up for grabs. He inherited a team that had quietly improved into contenders, not with a sudden bang but with a base at a time—built on speed, terrific defense and solid pitching. With Veeck’s usual bag of promotional tricks and a successful team on the field, White Sox attendance nearly doubled in 1959 to 1.4 million.

The symbol of new White Sox fortunes was Venezuelan native Luis Aparicio who, apart from being a brilliant shortstop, had taken the lead with a persistent strategy all but forgotten in the majors for 20 years: Stealing bases. While the rest of the AL was busy slugging away, the White Sox as a team had led the league in steals every year since 1951. Aparicio’s arrival in 1956 only intensified the Sox’ basestealing philosophy, leading AL players in his first three years with 21, 28 and 29 steals.

BTW: In fact, Aparicio would lead the AL in steals through each of his first nine seasons.

A Hare Among Tortoises

Throughout the 1950s, the American League was all about slow-footed sluggers—unless you wore the uniform of the White Sox, easily the decade’s most active and efficient team when it came to stealing bases.

Aparicio was just warming up. His 56 steals in 1959 would be the most by any major leaguer since 1943, igniting the “Go-Go Sox”—as they were now nicknamed—into a big-time threat to secure the pennant in the Yankees’ absence.

The Indians, led by 25-year-old Rocky Colavito (in the middle of completing back-to-back seasons with 40 home runs), led early but were overtaken by the White Sox in late July. They appeared ready to take it back a month later when they came to Chicago riding the momentum of an eight-game winning streak, trailing the Sox by just a game. But instead, the ensuing four-game series would be the death knell for the Tribe; the White Sox swept the series, built back their lead and never got seriously threatened again. To add insult to injury, the White Sox clinched their first pennant since the infamous 1919 Black Sox season at Cleveland on September 22.

BTW: In celebration, civil defense sirens blared in Chicago—alarming those who thought the Cold War was warming over. Mayor Richard Daley had to apologize.

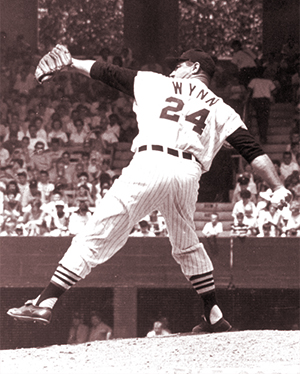

On a staff of proven veteran arms, no one shined more for the Chicago White Sox than Early Wynn, who won 22 to finish the decade with more wins (188) than any other major league pitcher. (The Rucker Archive)

The White Sox did have pitching, as anchored by 39-year-old veteran (and former Indian) Early Wynn—who won 22 games and a Cy Young Award; and they had the defense, the strength of which lay in the middle infield with Aparicio and second baseman Nellie Fox, both of whom won Gold Gloves.

Along with his outstanding glovework, Fox’s role as team leader on and off the field earned him the AL Most Valuable Player award, despite offensive numbers (.306 average, two home runs, 70 RBIs) that on paper weren’t going to knock any voters off their chairs.

BTW: Fox struck out only 13 times over 624 at-bats.

Rested, the White Sox opened the World Series with an 11-0 rout of a tired, emotionally spent Dodgers team traveling back-and-forth from California to the shores of Lake Michigan (first Milwaukee, then Chicago). The White Sox’ go-go philosophy of eking out a win was replaced by pure power thanks to Ted Kluszewski, once upon a time one of the most feared hitters in the game before persistent back problems neutralized his slugging abilities.

BTW: After hitting 171 home runs between 1952-55, Kluszewski managed only 14 over the next four years.

The Game One blowout was but an aberration for what was to follow, thanks largely to Los Angeles reliever Larry Sherry.

The Californian rookie had a shaky start when he entered Game Two in the eighth inning, allowing hits to the first three Chicago batters; but he rebounded to snuff out the rally. From there he was virtually untouchable whenever called to the mound—which was often. He bailed Don Drysdale out of an eighth inning jam in Game Three and held the Sox at bay from there; in Game Four, he shut down the Sox over the eighth and ninth innings, allowing the Dodgers to regain a lead they had lost in the seventh; and in Game Six, he took over for an ineffective Johnny Podres in the fourth, blanking the Sox on four hits the rest of the way as the Dodgers coasted to an 8-3 Series clincher. All in all, Sherry had a role in all four Los Angeles victories, winning two and saving two.

And what of the vaunted White Sox running game? It was go-go-gone, as Los Angeles catcher Johnny Roseboro kept Aparicio and Company constantly in check; in fact, the Dodgers out-stole the White Sox.

Two Often

In 17 years of managing, Al Lopez won two AL pennants, including the 1959 flag for the White Sox. But had it not been for the Yankees, Lopez might have gone down as one of the great pilots of all time; a record ten times over a 15-year period, Lopez’s teams finished second in the AL— nine of those years with the Yankees finishing first. No manager has placed runner-up more than Lopez.

After a rocky first year in California, all was well with the Dodgers once again. Fans swarmed to the Coliseum in droves for their first World Series, and the massive facility could hold it—with 92,000 seats filled for each of the Dodgers’ three home games. Owner Walter O’Malley sure loved the extra profits, as did the players—the huge attendance swelling the winning Series share per Dodger to $11,231.

And for the first generation of Los Angeles Dodgers baseball fans, there would be basking in both the Southern California sun and the coming age of newfound Dodger dominance.

Forward to 1960: A-Maz-ing! The Pittsburgh Pirates become one of the game’s unlikeliest champions with a historic walk-off home run by Bill Mazeroski.

Forward to 1960: A-Maz-ing! The Pittsburgh Pirates become one of the game’s unlikeliest champions with a historic walk-off home run by Bill Mazeroski.

Back to 1958: And Now, From Coast to Coast The Dodgers and Giants break the hearts of New Yorkers everywhere and head west to California.

Back to 1958: And Now, From Coast to Coast The Dodgers and Giants break the hearts of New Yorkers everywhere and head west to California.

1959 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1959 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1959 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1959 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1950s: A Monopoly of Success Though described as a golden age for baseball, most major league teams find themselves struggling—unless you’re in New York City, where the Yankees, Dodgers and Giants hog the World Series podium from 1950-56. But as the decade winds to a close, the euphoria of Big Apple baseball will rot overnight.

The 1950s: A Monopoly of Success Though described as a golden age for baseball, most major league teams find themselves struggling—unless you’re in New York City, where the Yankees, Dodgers and Giants hog the World Series podium from 1950-56. But as the decade winds to a close, the euphoria of Big Apple baseball will rot overnight.

The five-time Gold Glove outfielder recalls playing for the 1959 White Sox, Al Lopez, the Comiskey Park wall, and the one day he regrettably took greenies.

The five-time Gold Glove outfielder recalls playing for the 1959 White Sox, Al Lopez, the Comiskey Park wall, and the one day he regrettably took greenies. Ed Bressoud discusses the frustration of his one All-Star Game appearance, his relationship with Willie Mays and the sadness of the Giants leaving New York for San Francisco.

Ed Bressoud discusses the frustration of his one All-Star Game appearance, his relationship with Willie Mays and the sadness of the Giants leaving New York for San Francisco.